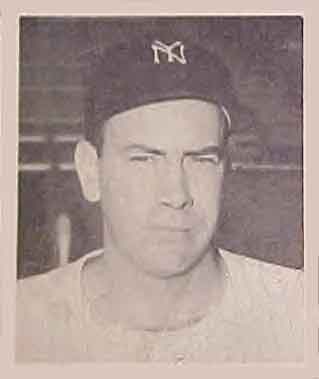

Bill Bevens

On October 3, 1947, Bill Bevens stood on the mound at Ebbets Field one out away from baseball immortality. He had pitched the first 8 2/3 innings of the fourth game of the World Series without giving up a hit. All he had to do was retire Brooklyn Dodgers pinch-hitter Cookie Lavagetto and he would become the first man to pitch a World Series no-hitter.

On October 3, 1947, Bill Bevens stood on the mound at Ebbets Field one out away from baseball immortality. He had pitched the first 8 2/3 innings of the fourth game of the World Series without giving up a hit. All he had to do was retire Brooklyn Dodgers pinch-hitter Cookie Lavagetto and he would become the first man to pitch a World Series no-hitter.

Bill stood six-feet-three and weighed 215 pounds in his prime. In 1946 he was a key member of the Yankees rotation, second only to Spud Chandler. A season later, he was manager Bucky Harris’s starter in Game Four. A win would give the Yankees a commanding 3–1 lead in the Series, which was as important to Bill as the no-hitter. What no one else in the ballpark knew, at this point Bevens was pitching largely on guts and guile. He had hurt his arm earlier in the game and had lost some speed off his fastball. Still, he thought he could get one more out. It was not to be.

Floyd Clifford Bevens was born on October 21, 1916, in Hubbard, Oregon, a small farming town about twenty-five miles south of Portland.1 Floyd was born to John Ezra and Edna Elizabeth (Jones) Bevens. He had three older brothers (Roy, Ray, and Henry) and an older sister Ruby. Two other siblings had died before he was born. His family grew hops and berries, and kept some animals. They needed Floyd, his three brothers, and his sister to do chores and help run the farm. Reminiscing about his childhood to a reporter in 1947, Bevens called his part of Oregon “a grand country to live in. What with the chores, my schoolboy life was a busy one.”2

Bevens described how he started pitching. “I went to grade school and then high school in Hubbard. I was a ballplayer in high school. Third base. Our coach was a man named Silkie. He needed pitching badly. He saw that I could throw hard. Well, the inevitable happened.”3

After high school, Bevens went to work at a garage and then at a cannery. He also played junior American Legion Ball for two years with the Woodburn, Oregon post. His team reached the national semifinals before losing to a team from Chicago, whose star pitcher was future Chicago Cubs first baseman Phil Cavarretta. After Legion ball Bevens pitched for semipro teams in Oregon while working at a warehouse. He also courted and married Mildred Louise Hartman.

Bevens’s success as a semipro attracted the attention of professional scouts, like the Yankees’ Joe Devine, who signed him in 1936. The Yankees sent the twenty-year-old right-hander to El Paso in the Class D Arizona-Texas League. In his first year in the minors, Bevens won sixteen games and struck out 179 men in 242 innings. (Sixteen was the most games Bevens ever won in a season, in the majors or the minors.)

Bevens progressed steadily through the Yankees farm system during the late 1930s and early 1940s. He won fourteen games for the Class B Wenatchee (Washington) Chiefs in 1938 and 1939, pitching a no-hitter each year. In 1940 he won fourteen for the Binghamton (New York) Triplets, the Yankees entrant in the Class A Eastern League. Bevens appeared ready to advance further, but his career stalled.

In 1947 he told an interviewer, “In 1941 I just couldn’t get going and was demoted to Augusta (Georgia) in the Sally League.”4 Bevens was 6-5 with Augusta after starting the season 0-7 with the Triplets. When the U.S. entered World War II, the Yankees transferred Bevens to the higher-level Pacific Coast League so he’d be closer to home if he got drafted. He won four and lost eleven for Seattle and Hollywood in 1942, then went 7-8 for Kansas City of the American Association in 1943.

At age twenty-six and married, Bevens did not get drafted. The Yankees brought him to spring training in 1944 and then promoted him to their top Minor League affiliate, the Newark Bears, where, he said, “I began to get somewhere. I won 12 and lost 6. I was asked to report to the Yankees about midseason, and won 4 and lost 1 in the American League. Once with the Yankees I decided that it was a far superior life to working in the minors and decided to stick.”5

Bevens’s first Major League victory was against the Boston Red Sox in the heat of a pennant race. He also won a key game at the end of the ’44 season that put the Yankees in position to take the pennant if they could only win the last four games against the St. Louis Browns. The Yankees lost the first game and were eliminated as the Browns captured their only twentieth century flag.

Bevens attributed his success in the majors to his control. “I began to get somewhere in 1945 because I developed my control to the point at which I was able to keep my passes down.”6 He went 13-9 in 1945, and then 16-13 with a 2.23 ERA in 1946, walking only 78 men in 249 2/3 innings. Eight of Bevens’s thirteen losses in 1946 were by one run, including two 1–0 defeats.

Bevens prided himself on staying in shape by working out during the off-season. He refereed high school and college basketball games to keep his legs strong. His off-season job in the cannery also built up muscle. He threw a fastball, curve ball, and change-up but stayed away from more exotic pitches like the knuckle ball. Bevens told a reporter during the 1947 season, “I never have suffered from a sore arm. I throw hard every day. You cannot expect your arm to be strong if you do not exercise it.”7 Even though Bevens was in good shape, he suffered from poor run support and lost almost twice as many games as he won in 1947, finishing with a 7-13 record and a 3.82 ERA.

The Yankees went into Game Four of the 1947 World Series up two games to one, with a chance to take a commanding lead. While he had allowed no hits when he faced Lavagetto with two outs in the ninth inning, his ten walks broke a Series record set by the Philadelphia Athletics’ Jack Coombs thirty-seven years earlier. Brooklyn scored a run in the fifth inning on two walks, a sacrifice, and a ground out. Meanwhile, the Yankees managed two runs, which looked like enough for the win.

In the ninth inning the Dodgers came up for their last chance. Bevens got Bruce Edwards to ground out to start the inning. One down. Then he walked Carl Furillo. Spider Jorgensen popped up in foul territory for the second out. Al Gionfriddo, running for Furillo, stole second. Pete Reiser, unable to play in the field because of a leg injury, hobbled up to the plate to pinch hit. With first base open, Bevens pitched the dangerous Reiser carefully. When the count reached 3-1, Harris ordered an intentional walk to Reiser, violating the fundamental precept of putting the potential winning run on base. Eddie Miksis ran for Reiser. Dodgers manager Burt Shotton sent the right-handed-hitting Lavagetto up to bat for Eddie Stanky, also a right-handed hitter.

“The book said Lavagetto couldn’t handle hard stuff away,” Bevens said many years later. “That’s what I gave him.” The first pitch was on the corner for strike one. As it turned out, the book the Yankees had on Lavagetto was wrong. “Fast and tight was the way to handle me,” Lavagetto said.8

Bevens’s next pitch was in the same place, and Lavagetto lined it over Tommy Henrich’s head off the right-field wall. With two outs the runners were off at the crack of the bat, and Miksis scored all the way from first with the winning run. Bevens said the next day that after Lavagetto’s hit he “felt like a guy who had dropped ten stories in an elevator. My heart and my brains and everything was right down by my spikes.”9

While the Dodgers celebrated at home plate, Bevens turned and walked slowly to the clubhouse. The Yankees kept the door closed after the game for more than a half-hour while they tried to regroup. Afterward, they put the best face on it they could, praising Bill’s effort and vowing to win the World Series anyway.

Win it they did, and Bevens made a significant contribution in the seventh and deciding game. After Frank Shea gave up two runs to Brooklyn in the second inning, Bevens relieved him and pitched 2 2/3 scoreless innings before leaving for a pinch hitter. Joe Page pitched the last five innings and got the win. Bevens was able to pitch only because his wife Mildred stayed up the night before the game massaging his right arm.

Nothing could restore Bevens’s arm for the 1948 season. At the time it was reported that his struggles were caused by a leg injury he suffered while refereeing a basketball game during the off-season However, some years later, Bevens told reporter Tom Meany that his arm went dead during the World Series.

Bevens and the Yankees tried everything and anything to get his arm to come back. He even suffered a quack doctor injecting his arm with saline solution, but nothing worked. Bevens was sold to the White Sox on a conditional basis in January 1949 and then returned by the White Sox on March 28. He reported to Minor League spring training and then was released by the Yankees on April 18.

For several years after that, Bevens tried to pitch professionally. In 1950 he pitched for Sacramento in the Pacific Coast League but was released and went to San Diego. His arm had improved but his pitching hadn’t. Bevens said, “Although I couldn’t pitch winning ball, my arm no longer gave me any trouble.”10

In 1951 he pitched for the Salem (Oregon) Senators in the Western International League, going 20-12 with a 3.08 earned run average in this Class B minor league. He took comfort from pitching in his hometown, where Mildred and his three sons, Larry, Danny, and Bobbie, could watch him. As a former Major League pitcher, and only four years removed from his “almost” no-hitter, Bevens was a celebrity in the league and attracted reporters after every game.

Bevens’s success in Salem earned a trip to San Francisco in the PCL in 1952, where he was 6-12 with a 4.47 ERA in 155 innings. He tried again with Salem the next year, but the thirty-six-year-old Oregonian’s baseball career was at an end. He returned home to Salem to raise his family. Eventually he stopped working at the local cannery and worked his way up to manager of a trucking company.

Baseball fans remembered Bevens. Almost to the day he died, people would regularly ask Bevens about the almost no-hitter, said his son Larry. Bevens was never angry or regretful. “I don’t think he ever had any sense of ‘Gee whiz, what if,’” Larry said. “He didn’t toss or turn, or end up bemoaning Lavagetto’s hit.”11

Bevens died on October 26, 1991, from lymphoma, at the age of seventy-five. Every obituary led with mention of the fourth game of the 1947 World Series. So in the end Bevens did achieve baseball immortality, even if it was the “close-but-didn’t-quite-make-it” kind. He did make a significant contribution to a world championship team.

Bevens was survived by his wife Mildred, whom he married in 1936, his three sons, eight grandchildren, and six great-grandchildren. No doubt Bevens considered his marriage of more than a half-century, and the size of his extended family more than enough compensation for losing his no hitter.

In a piece on Bevens for Collier’s magazine in 1951, author Tom Meany wrote that a reporter asked Bevens, “How do you feel about being one out away from glory? When you think back about that game and realize that Lavagetto’s hit cheated you of something nobody else had ever done, what are your reactions?”

“Well,” answered Bevens, “I figure I was lucky to be up there in the first place.”12

This biography is included in the book “Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by Lyle Spatz. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Notes

1. There are several unconfirmed version of how Bevens acquired the name Bill.

2. Daniel M. Daniel, “Bevens, Big Modest, Reticent Hombre Heads for Hurling Heights with Yanks” – Baseball Magazine, June 7, 1947, p. 227.

3. Ibid. p. 227.

4. Ibid. pp. 227-228.

5. Ibid. p. 228.

6. Ibid.,p. 228.

7. Ibid. p. 228.

8. Ibid. p. 229.

9. Bill Bevens as told to Jack Cuddy in New York, published in the Detroit News, October 4, 1947.

10. Tom Meany, “Hard Luck Keeps Bill Pitching,” Collier’s, July 28, 1951.

11. Sean Kirst, “Almost immortality: The Baseball Heartbreak of Bill Bevens,” Syracuse Post-Standard, October 14, 2010.

12. Tom Meany, “Hard Luck Keeps Bill Pitching,” Collier’s July 28, 1951.

Full Name

Floyd Clifford Bevens

Born

October 21, 1916 at Hubbard, OR (USA)

Died

October 26, 1991 at Salem, OR (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.