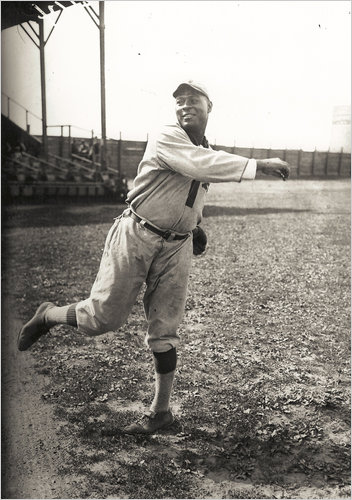

Bill Gatewood

If his only claim to fame had been giving a young pitching prospect named James Bell his nickname, “Cool Papa,” he would have perhaps been the answer to a baseball history trivia question. Had his sole contribution to the story of the game been that of teaching a young Satchel Paige how to throw what became the notorious ‘hesitation pitch,’ his place in the history of the sport would have been small, but secure. “Big Bill” Gatewood not only achieved those two items, he also became the first pitcher to throw a no-hitter in the Negro National League, along with a second a few years later. The tall right-hander1 used guile, intelligence, size and aggression, along with a serviceable bat, to carve out a baseball career that lasted more than three decades. He was, in the words of historian James Riley, “a tremendous pitcher in the early years of black baseball.”2

If his only claim to fame had been giving a young pitching prospect named James Bell his nickname, “Cool Papa,” he would have perhaps been the answer to a baseball history trivia question. Had his sole contribution to the story of the game been that of teaching a young Satchel Paige how to throw what became the notorious ‘hesitation pitch,’ his place in the history of the sport would have been small, but secure. “Big Bill” Gatewood not only achieved those two items, he also became the first pitcher to throw a no-hitter in the Negro National League, along with a second a few years later. The tall right-hander1 used guile, intelligence, size and aggression, along with a serviceable bat, to carve out a baseball career that lasted more than three decades. He was, in the words of historian James Riley, “a tremendous pitcher in the early years of black baseball.”2

William Miller Gatewood was born on August 22, 1881, in San Antonio, Texas. His father hailed from Maryland and his mother from Texas. Neither of their names is known.3 While he only achieved an eighth-grade education, he proved to be more than capable at his profession, that of baseball.

Not a great deal of detail has been recorded or preserved about Gatewood’s early years. There are at least two newspaper accounts of 1904 games between the St. Louis Four Hundreds and both the Chicago Union Giants and a team from Grand Rapids, Michigan.4 While the location, St. Louis, supports the possibility that Bill Gatewood played in the games, definitive corroboration is impossible. The earliest confirmed documentation shows that he appeared in what was likely his first professional baseball game in 1906, as a first baseman for the Leland Giants. Later that year, he also appeared for the Cuban X-Giants.5 He spent 1907 and 1908 with the X-Giants and the Philadelphia Giants before signing as the primary pitcher with the St. Paul Gophers.6 In 1909, Gatewood rejoined the Leland Giants, and played a slate of games against the associated Western Independent Clubs, a group that included the powerful Kansas City Giants and the Buxton Wonders, a mining-town team from south-central Iowa. In Chicago, playing for manager Rube Foster, Gatewood played well enough to start two playoff games against St. Paul, and was named to writer Harry Daniels’s figurative “1909 All-American Team.”7

It was under Foster’s tutelage that Gatewood developed his skill at doctoring the baseball, and the young pitcher was soon widely acknowledged as a practitioner of both the spitball and the emery ball.8 The lanky player took a brief hiatus in 1910, opting instead to manage the Minneapolis Keystones,9 a touring club of very old and very young black players. The change of roles lasted but a year, and in 1911 Gatewood joined the Chicago Giants as a pitcher and first baseman. This squad, however, was not Foster’s. Following a split between owner Frank Leland and Foster before the 1910 season, the former launched a new team (the Chicago Giants) while the latter took over the Leland Giants.

Foster renamed the Leland Giants as the Chicago American Giants for the 1911 season and, a year later, Gatewood returned to Foster’s fold and remained with the American Giants until the end of the 1913 campaign. In June of 1912, though, the big man’s temper emerged. In the tenth inning of a game against a local white team called the West Ends, “[West End batter] Torrey beat out a hit to [Bill] Monroe and the decision so enraged Gatewood [pitching at the time] that he stepped on [umpire] Conley’s foot and was put out of the park.” Charles Dougherty, in relief of Gatewood, promptly gave up the game-winning hit, and the West Ends won, 7-6.10 The following winter, between the 1912 and 1913 seasons, Gatewood travelled west with the barnstorming American Giants, playing as far away as San Diego in late December.11

In 1914, fresh off the west coast trip, Gatewood again fell prey to the instability of life as a black baseball player, moving yet again, this time to the New York Lincoln Giants. The stop afforded him the chance to play alongside Spottswood Poles, Cyclone Joe Williams, Louis Santop and – again – Grant “Home Run” Johnson, who was closing out his fabulous diamond career with one, final season. Gatewood returned to Chicago, to the American Giants, for 1915, but was released in mid-summer as Foster was tinkering with his lineup. The pitcher soon signed with the St. Louis Giants, and remained with them until the 1917 campaign.12 Of note, the pitcher also tossed the first of the two no-hitters with which he is credited, on May 13, 1916, against the Cuban Stars. St. Louis won the game, 4-1.13

In mid-1917, at age 38 and now playing for C. I. Taylor on the Indianapolis ABCs, he submitted his military draft registration card. That card indicated that his permanent home remained in St. Louis, but that he currently worked for the ABCs. Of note, Taylor evidently intended to shift the aging star to become the primary catcher,14 although that arrangement did not sustain itself over the longer term.

The next year, Gatewood finally married. He and his wife, LouEmma (Abbot), a registered nurse, eventually had four sons (William Jr., Carl, James, and Frank) and a daughter, Ann. They remained married until LouEmma died in 1947.

Gatewood continued to travel the land in search of baseball employment. He played with both the St. Louis Giants and the Bacharach (Atlantic City) Giants in 1919, and in June of 1920 joined the Detroit Stars. The new assignment was noteworthy in that Detroit was one of the original entries in Rube Foster’s new Negro National League. Playing at Mack Park in Detroit and managed by Pete Hill, the Stars would end the inaugural league season in second place, almost inevitably trailing only Foster’s American Giants.

On June 6, 1921, Gatewood added yet another achievement to his baseball resume, throwing the first no-hitter in Negro National League history. Facing only 29 batters, Gatewood shut down the Cincinnati Cuban Stars, a team that included future Cuban Baseball Hall of Famer Valentín Dreke, on only two walks. Gatewood also struck out ten, and added a home run of his own to cement the 4-0 victory.15 Historian Larry Lester, in his biography of Rube Foster, added a bit of detail:

“In a 1921 game, as a member of the Detroit Stars with Bruce Petway catching, the Cuban Stars protested to the umpire that the ball was doing ‘funny things.’ The umpire examined the ball and found a nick and tossed it out of play. A short time later more complaints were registered and …The Cubans demanded that Gatewood be searched. The pat down revealed a half-dozen bottle caps in (the pitcher’s) pocket. Busted and now angry, Gatewood started off batters with knock-down pitches and eventually struck out 10 and walked two batters en route to a no-hitter.”16

The next year, 1922, after yet another winter west-coast barnstorming swing,17 Gatewood returned to Missouri, this time as player-manager of the new St. Louis Stars. While the team was pedestrian, finishing league play with a 29-37 record, they did have on the roster a 19-year old pitcher, James Bell. While the story is impossible to confirm beyond doubt, historian Gary Ashwill presents a discussion of alternative explanations on the website “Agatetype.com.”18 The most likely story is that Gatewood watched his young pitcher strike out none other than Oscar Charleston at a critical time in one particular game. Gatewood noted how “…’cool’ the nineteen-year-old had been under pressure; [he also] added the “Papa” to make the name sound better, and the nickname became a permanent part of Bell’s persona. Gatewood made a much more important contribution to Bell’s success when he changed him from a pitcher to an everyday player and switched him over to swing from the left side to utilize his speed.”19

The aging star still pitched in a part-time capacity over the succeeding seasons with the Toledo Tigers, the Milwaukee Bears, the Memphis Red Sox, the Albany (Georgia) Giants, and the Birmingham Black Barons.20 In 1928, with Birmingham, Gatewood managed a young pitcher named Leroy ‘Satchel’ Paige, occasionally “renting” him out to other clubs so that both player and manager could make a bit of extra money.21 Paige also credited Gatewood with teaching him the elements of the former’s notorious “hesitation pitch” while the two were on the Black Barons.22

Unable to pitch effectively at the highest levels any longer, the 48-year old returned to his home in Moberly, Missouri. He managed, and pitched for, the local club team, the Moberly Eagles,23 and even had the chance to manage a young outfielder named Jimmie Crutchfield. “Crutch” would go on to star with the Pittsburgh Crawford teams of the mid-1930s and with the Chicago American Giants in the 1940s, and even teamed with now-outfielder “Cool Papa” Bell on the 1935 Crawfords, perhaps the greatest team in the history of the Negro Leagues.24

The Moberly Eagles were re-dubbed the Gatewood Browns in late 1929, and Gatewood remained with them in various capacities well into his 50s. The team featured the former star in exhibitions throughout the area. In one particularly memorable contest in 1939, the 58-year old manager put himself in a game as a pinch hitter with his son, William Jr., on third. “The elder Gatewood hit a slow roller to short and young Gatewood brought in the tying run.”25 Evidently, the game’s grip on the elder was too strong for age to sever.

Gatewood was working as an attendant at a convalescent home in Columbia, Missouri, where his wife worked as a nurse, in 1947.26 That April, LouEmma died at the age of 56 of what was termed “chronic myocarditis and resultant arteriosclerosis,” more commonly, and generically, termed heart disease.27 Even that tragedy, however, was not enough to force Gatewood off the diamond. In September 1949, he was still managing the Gatewood Browns, even if it was for amateur Sunday-afternoon tilts against other local teams.28

Bill Gatewood died of “cancer of stomach” after a month-long battle at the Ellis Fischel Hospital in Columbia, Missouri, on December 8, 1962. He was 81. The death certificate identified a surviving wife, Elanor Gatewood, and noted his occupation only as “laborer.”29 There are no other details about his second wife, although they certainly wed sometime between 1947 and 1962. Gatewood was buried at Memorial Park Cemetery in Columbia, although he was interred in an unmarked grave. The Society for American Baseball Research, via the Negro Leagues Baseball Grave Marker Project, corrected that oversight in 2010.30

“Big Bill” Gatewood enjoyed the sort of baseball life of which most players can only dream, albeit a relatively anonymous one, at least in contrast to the careers of his Caucasian counterparts. He played with, and for, legends of the game like Grant “Home Run” Johnson, who had played on the Adrian (Michigan) Page Fence Giants, Rube Foster, Oscar Charleston, Ben and C.I. Taylor, Pete Hill…the list goes on and on. He nicknamed “Cool Papa” Bell, and taught a type of pitch to Satchel Paige, who became one of the greatest hurlers in the history of the sport. He threw the first no-hitter in the annals of the first Negro National League, and influenced scores of players who came after him. His influence echoed throughout the history of the Negro Leagues, and beyond.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Phil Williams and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 There is some question as to Gatewood’s precise height, with various references listing a range between 6’4” and 6’7”. His draft registration card for World War I merely notes that in the ‘tall/medium/short’ height continuum, Gatewood was considered “tall”.

2 James Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of Negro Leagues Baseball (New York: Carroll and Graf, 1994): 309.

3 1940 Census

4 “Four Hundreds vs. Grand Rapids,” St. Louis Republic, July 2, 1904: 4; “Four Hundreds – Chicago Giants,” St. Louis Republic, June 19, 1904: 27.

5 Most playing information, regarding teams and recorded statistics, was culled from the Negro League database within the website Seamheads.com (seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=gatew01bil).Where other information is used, it is cited accordingly.

6 Rockford (Illinois) Register-Gazette, April 29, 1908: 5.

7 Harry Daniels, “The Baseball Spirit in the East,” Indianapolis Freeman, December 25, 1909:7.

8 Riley, 309

9 seamheads.com/NegroLgs/manager.php?ID=281

10 “West Ends Take Game in 10th, 7-6,” Chicago Tribune, June 3, 1912: 13.

[11]“Bears Romp Away from Giants, 8-1,” San Diego Union, December 30, 1912: 8.

12 Chicago Tribune, September 1, 1915: 13.

13 Online: sabr.org/bioproj/topic/ahead-their-time-negro-leagues-no-hitters, accessed: May 24, 2019

14 Indianapolis Star, March 24, 1918: 24.

15 “No-Hit Victory to Gatewood,” Detroit Free Press, June 7, 1921: 18.

16 Larry Lester, Rube Foster in his Time: On the Field and in the Papers with Black Baseball’s Greatest Visionary (Jefferson: McFarland and Co., 2012): 68

17 San Diego Union, February 6, 1922: 8.

18 Gary Ashwill, “How Cool Papa Got His Name” on the site “Agate Type”, online: agatetype.typepad.com/agate_type/2006/07/how_cool_papa_g.html, accessed July 22, 2019. The author cites accounts from both James Riley’s Biographical Encyclopedia and John Holway’s Complete Book of Baseball’s Negro Leagues, and then evaluates corroborating material. In reality, the absolute truth may be unknowable.

19 Riley, 310.

20 Online: nlbemuseum.com/nlbemuseum/history/players/gatewood.html, accessed: April 5, 2019.

21 Interview of Satchel Paige as in inset piece in the Des Moines Register, May 31, 1962: 13.

22 Riley, 310.

23 “Eagles Win 13-inning Game at La Plata,” Moberly (Missouri) Monitor, May 26, 1930: 8.

24 Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum at the Heinz History Center, Pittsburgh, PA; Online: heinzhistorycenter.org/exhibits/negro-league-baseball, accessed: May 29, 2019

25 “Browns-Buffalo Game Halted by Rain in Tenth,” Moberly (Missouri) Monitor, May 15, 1939: 2.

26 U.S. Department of War, “Draft Registration” card for William Miller Gatewood, 1946.

27 Missouri Death Certificate for L. Gatewood, number 38-3006-7853, filed April 2, 1947.

28 “Oliver Harvey Nine to Face Old Timers Sunday Afternoon,” Moberly (Missouri) Monitor, September 29, 1949: 5.

29 Missouri Death Certificate for W. Miller, number 62-041598, filed December 10, 1962.

30 Online: findagrave.com/memorial/54329524

Full Name

William Miller Gatewood

Born

August 22, 1881 at San Antonio, TX (US)

Died

December 8, 1962 at Columbia, MO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.