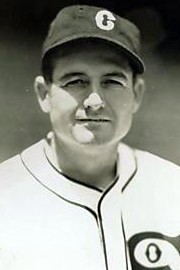

Bill Shores

Bill Shores was not a superstitious player. After winning 23 games as a promising swingman for the Philadelphia Athletics championship teams in 1929 and 1930, he became the first big-league player to wear number 13 when he asked for the jersey in 1931. Then he suffered a string of unfortunate incidents: infected toe, hit by a batted ball, influenza, and a career-threatening shoulder injury. In midseason of ’31, the Athletics released him. He made appearances with the New York Giants in 1933 and the Chicago White Sox in 1936, but he did not don number 13.

Bill Shores was not a superstitious player. After winning 23 games as a promising swingman for the Philadelphia Athletics championship teams in 1929 and 1930, he became the first big-league player to wear number 13 when he asked for the jersey in 1931. Then he suffered a string of unfortunate incidents: infected toe, hit by a batted ball, influenza, and a career-threatening shoulder injury. In midseason of ’31, the Athletics released him. He made appearances with the New York Giants in 1933 and the Chicago White Sox in 1936, but he did not don number 13.

William David Shores was born on May 26, 1904, in Abilene, Texas. Not long after his birth, his parents, Reginald and Willie Shores, native Texans, moved to Lawn, a small, recently founded settlement of about 100 people (mostly ranchers) 25 miles south of Abilene. The Shores raised five children (Ottice, Bill, Howard, Madeline, and Mozell). His father operated a blacksmith shop and later managed a farm that raised horses for polo players. Not much is known about Bill’s early years. Along with his older brother, Ottice, he began his education in a one-room schoolhouse in Lawn before a larger brick one was built in 1912. Although Shores reported on the 1940 census that he went to high school for four years, his son, Michael (born in 1945) doubted that his father ever finished high school.1 According to the 1940 census, Shores married Georgia Zimmerle when they were of high-school age, 17 and 15 years old, respectively. Together they had two daughters, Billie and Betty Joe, born between 1923 and 1925.

One aspect of Shores’ life is certain: He loved baseball and dreamed of being a big leaguer. By all accounts he was on the diamond as often as possible. Abilene fielded its first professional team, the Eagles of the Class D West Texas League, in 1920 around the time Shores reportedly began pitching for local semipro teams.2 His success caught the attention of Roy Mitchell, a former big-league pitcher and the manager of the Temple Surgeons of the Class D Texas Association. Shores signed with the Surgeons in 1925, but was cut loose during the season. The following season, Shores tried out for the Corsicana Oilers of the same league; he made the team, but was released early in the season having pitched only a few games. With his family 250 miles away, the resilient Shores was not about to give up. He went to Mexia, a booming oil town 35 miles south of Corsicana in East Texas, and caught on with the Gushers. His third team in the Texas Association was a charm: Shores became a star. The Mexia Daily News reported on his pitching success (he was a combined 14-11 in 228 innings), and also his sale for $4,000 to the Wichita Falls Spudders of the Class A Texas League.3

Shores was a rugged man’s man, 6 feet tall and weighing 185 pounds. The hard-throwing right-hander with a knee-buckling curveball struggled in his month with the Spudders (1-3, 4.50 ERA in 30 innings), but his potential intrigued Connie Mack and the Philadelphia Athletics. They purchased his contract in the offseason and invited him to Fort Meyers, Florida, in 1927, to participate in spring training. The Sporting News reported that the “curving juvenile” was expected to compete for a roster spot; however, securing a spot on the staff that led the American League in ERA in 1926 was not an easy prospect.4 Shores was optioned to the Waco Cubs of the Texas League. The ace of the staff, “Big Bill” was one of the hardest-to-hit pitchers in the league, won 14 of 21 decisions and posted the league’s third best ERA (2.99) while logging 217 innings. He led the league with 125 strikeouts.

“The promising member of Connie Mack’s family” was back in spring training with the Athletics in 1928.5 Described as a “dependable second stringer,” Shores was the only recruit pitcher to land a spot on the staff and didn’t wait long to make his big-league debut.6 After the reigning champion New York Yankees knocked around Lefty Grove for five runs in the first three innings on Opening Day, Shores was baptized under fire. He tossed three innings, surrendering five hits and two runs in the 8-3 loss at Shibe Park. Shores waited six weeks for his next outing. The United Press later reported the reason for the long delay: Shores “appeared headed for a regular berth … when he injured his pitching arm in a wrestling match with another rookie.”7 On May 23 Shores took the mound again in a surprise start against the Washington Senators, whom he held scoreless through eight innings, ultimately settling for a complete-game four-hitter for his first major-league win. Less than a week later, the Athletics traded him along with pitcher Jing Johnson to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League for pitcher George Earnshaw. Following three losses in five appearances with the Orioles, Shores was reassigned to Wichita Falls. In just over two months with the Spudders, Shores regained his form by winning eight of 11 decisions and posting the league’s fourth best ERA (2.88). He was named to the league all-star team.8

If injuring his arm roughhousing with a teammate was not enough to draw the ire of Connie Mack, Shores’ holdout prior to spring training in 1929 was. “I don’t pay a nickel more to anyone on the club than I have offered,” said the Tall Tactician in response to the holdouts by Shores and especially Mickey Cochrane. “It’s up to the player to decide if he wants to play for that salary.”9 Shores signed in mid-March only after Mack threatened to release him,10 but reported to camp overweight and out of shape. Consequently, Mack ignored the 25-year-old right-hander and he saw limited action in spring training. The Athletics boasted the majors’ best pitching staff, led by their starting trio (Grove, Earnshaw, and Rube Walberg); however, Mack realized that he needed a dependable young arm to support veteran swingmen Eddie Rommel and 45-year-old Jack Quinn. The only rookie to make the team out of spring training, Shores was brought along slowly. Debuting in the 11th game of the year, he established himself as a nifty fireman with two wins and five saves (the saves, which were not a statistic at the time, were compiled by latter-day baseball historians), which earned him his first major-league start in more than a year. In the second game of a doubleheader against Boston on June 25, he hurled a complete-game 8-2 victory and struck out a career-high seven batters. About three weeks later he was given another start and responded by tossing the first of two career shutouts, a five-hitter against the St. Louis Browns. Shores was hailed as “sensational” and “one of the important men” in the A’s drive to their first pennant since 1914.11 “Fat Boy Makes Good” wrote nationally syndicated sportswriter Henry L. Farrell of Shores’ unlikely transformation from a training-camp outcast to an integral part of the major leagues’ best staff.12 Mack was effusive in his praise: “Shores is a great pitcher. When we were at training camp, I never expected him to be of any use to me. [He’s] the biggest surprise of the year.”13 Splitting his time between starts and relief outings for the remainder of the year, Shores tossed a career-best ten-inning complete game on September 20 to defeat the Tigers, 2-1, giving rise to speculation that he might be in line for a start in the World Series. He finished the season with an 11-6 record and an impressive 3.60 ERA in 152? innings.

With 104 victories, the Phillies cruised to the pennant and defeated the upstart Chicago Cubs in five games in the World Series. From a pitching standpoint, the Series was strange for the A’s: Grove neither started nor won a game, yet ageless wonder Quinn did, and 35-year-old submariner Howard Ehmke entered baseball lore with a complete-game victory and World Series record 13 strikeouts in Game Two. Shores did not see action, and one day after the Series the New York Times offered an explanation:

“The New Jersey road patrol broke into the world’s series dope by arresting Bill Shores, young athletic pitcher, for speeding just outside Camden last night. The whisper around the Mack camp is that Shores was supposed to pitch, but did not because of the lost sleep, to say nothing of his mental duress . . .”14

The embarrassment of the arrest and the squandered chance to start in the World Series may have helped Shores refocus on baseball. Unlike the previous year, Shores signed his contract early, spent several weeks getting in shape in Hot Springs, Arkansas, with a few other veterans, and then reported early to spring training in Fort Myers. He was expected to battle rookie Roy Mahaffey (coming off two consecutive 20-win seasons in the minors) for the fourth spot in the starting rotation. Shores got his chance in early May and tossed complete-game victories (yielding just three earned runs) in his first two starts of the year. After two poor starts, Shores surrendered six runs against the Yankees without registering an out, and consequently lost his position in the starting rotation. After battling the Senators for most of the season, the Athletics took charge of the pennant in August and built a comfortable lead. Shores enjoyed the best stretch of his career during the last two months of the season. With ten starts among his 13 appearances, he won seven of eight decisions, and his stellar 2.76 ERA (in 78 innings) trailed only Grove’s. With a 102-52 record, the A’s captured their second consecutive pennant with the most balanced team in baseball. Enjoying his best season, Shores made 19 starts among his 31 appearances, logged 159 innings, and won 12 of 16 decisions. His ERA (4.19) trailed only that of the immortal Grove.

The A’s took a two-games-to-none lead over the Cardinals in 1930 World Series as Grove (28-5) and Earnshaw (22-13) pitched complete-game victories. When sportswriters asked Mack if Shores would start Game Three or if Mr. McGillicuddy would “pull another Ehmke,” he responded, “I don’t know myself.”15 Mack played his cards close to his vest. Shores got into Game Three, but as a reliever. He replaced Walberg with two outs and two men on in the fifth inning and the Athletics down 2-0. He retired Taylor Douthit to end the inning, then pitched a 1-2-3 sixth inning, but ran into trouble in the seventh. He surrendered three consecutive singles leading to two runs, and was replaced by Jack Quinn. Grove and Earnshaw pitched the final 27 innings of the series to capture the A’s second consecutive title.

“I’m just a country boy trying to get going,” said Shores as he prepared for spring training in 1931.16 The burly Texan’s arrival in Fort Myers was greeted by stories touting him as likely “one of the biggest winners in the league.”17 Expectations turned sour when Shores came down with shoulder problems during camp (he also suffered from a toe infection and a serious case of influenza),18 and saw limited action. After he made six ineffective appearances in the first two months of the season, the Athletics cut their ties with him, releasing him outright to the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League. Shores won eight of 11 decisions with the Beavers but the stress of his demotion and move across the country had a profound effect on his health. His season ended prematurely when he was hospitalized for bleeding stomach ulcers.

With his career at a crossroads, Shores responded with his best year in pro ball. He won 19 games (tied for fifth best in the PCL) and logged a career-high 260 innings. With a devastating fastball, he struck out 15 batters in a two-hit victory over Seattle in August and finished the season among the league leaders with 164 strikeouts. When he was passed up in the annual baseball draft, his chances for another shot on the big stage seemed slim. But his luck soon changed when the New York Giants acquired him in exchange for pitcher Sam Gibson and cash.

Once again touted as a potential starter, Shores pitched well in camp, but had little chance to break into a starting rotation consisting of Carl Hubbell, Hal Schumacher, Freddie Fitzsimmons, and Roy Parmelee, who combined for 73 wins and more than 1,000 innings in 1933. The Giants had the best staff in baseball as attested by their 2.71 ERA, the lowest in either league since 1920. After just two relief appearances, Shores was assigned to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association in late May. He went 8-11 in three months of work for a terrible team. On August 27 he was hit in the head by a line drive and appeared to be unconscious; however, he got up, struck out the side, then left the game for medical treatment. No one ever doubted Shores’ toughness. The next day the Giants recalled Shores for their pennant drive.19 A solid contributor in the final month of the season, Shores started three times, relieve three times, and won twice. On September 16 at Wrigley Field he pitched the last complete game in his big-league career to defeat the Cubs, 6-3. Shores did not pitch in the Giants’ victory over the Senators in five games in the World Series, but was voted a half-share of World Series winnings.

The life of a marginal player is unstable, and often the product of luck and timing. Success, as measured by a roster spot, requires perseverance and a passion for the game. Shores had both. The euphoria of his third championship lasted only through spring training when the Giants released him outright to the Blues. It would be almost three years before the Texan made it back to the big leagues. He missed most of 1934 with shoulder problems and was demoted to the Dallas Texans in the Texas League the following season. Now the property of the White Sox, Shores pitched well enough (11-7, 2.81 ERA) to be reassigned to Kansas City in 1936. Though still suffering from shoulder miseries, he logged 144 innings with the Blues and was called up by the White Sox in mid-July to shore up their relief corps. Shores made his final nine big-league appearances (all relief outings in mop-up duty) and posted an unsightly 9.53 ERA in 17 innings. The White Sox severed ties with Shores in the offseason, trading him and two other players to Dallas for catcher Tony Rensa.20

Shores toiled in the Pacific Coast League in his final four years in Organized Baseball (1937-1940). After the San Francisco Seals acquired him from Dallas prior to the 1937 season, he experienced a rejuvenation of sorts. In his three years with the Seals, he won 44 games and logged more than 600 innings. Newspaper reports of the time refer to him as a “knuckle-ball pitcher” suggesting that he reinvented himself to prolong his career and overcome his chronic shoulder pain.21 It is unclear when and from whom Shores learned the knuckler; however, he played with three of the best known knucklers of his era: Eddie Rommel (the father of the modern knuckler), Freddie Fitzsimmons, and Ted Lyons. A short, unsuccessful stint with the San Diego Padres concluded his professional career.

For the first player to wear number 13, Shores had a pretty lucky career. A member of three championship teams, he played with and was managed by Hall of Famers. He was released outright no less than four times, but played for 14 teams, won 170 games, and logged in excess of 2,500 innings in his 16-year professional baseball career.

After his release from the Padres, Shores returned to the San Francisco area to settle down with his second wife, Christine, a nurse whom he had married in 1938, and daughters Billie and Betty Jo. Michael was welcomed to the family in 1945. After failing to land a coaching position in the newly established California League in 1941, Shores gradually drifted away from baseball. He and his family relocated to Modesto, where he worked as a salesman at an electronics and appliance store. Following a second divorce, he married Vertis Page, an Oklahoman. They moved to Lexington, outside of Oklahoma City, in the 1960s.

Bill Shores died after an extended illness on February 19, 1984, at the age of 79, in Purcell, Oklahoma, and was buried at nearby Lexington Cemetery.

Sources

Newspapers

Abilene (Texas) Daily Reporter

Abilene (Texas) Morning News

Albert Lea (Minnesota) Evening Tribune

Altoona (Pennsylvania) Mirror

Cumberland (Maryland) Evening News

Jefferson City (Missouri) Post-Tribune

Mexia (Texas) Daily News

Milwaukee Journal

New York Times

Oelwein (Iowa) Daily Register

Reno Evening Gazette

The Sporting News

Syracuse Herald

Titusville (Pennsylvania) Herald

Online sources

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Other

Bill Shores player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Notes

1 Garner Roberts, “The Lawn, Texas Lad,” ReporterNews. Your Abilene Online, August 13, 2006. http://reporternews.com/news/2006/aug/13/the-lawn-tex-lad/?print=1.

2 “Lawn News Notes,” Abilene Daily Reporter, April 1, 1924, 5.

3 Gushers Back Home for Final Three games of Texas Association Year,” Mexia (Texas) Daily News, August 20, 1926, 8.

4 The Sporting News, March 3, 1927, 2.

5 The Sporting News, March 22, 1928, 6.

6 The Sporting News, April 5, 1928, 1.

7 George Kirksey, United Press, “Philadelphia Athletics Will Have These Changes” Oelwein (Iowa) Daily Register, February 15, 1929, 4.

8 The Sporting News, November 29, 1928, 5.

9 “Cochrane Holdout,” Cumberland (Maryland) Evening News, February 22, 1929, 17.

10 “Training Camp Activities,” Titusville (Pennsylvania) Herald, March 1, 1929, 8.

11 Henry L. Farrell, “Hooks and Slides,” Jefferson City (Missouri) Post-Tribune, July 27, 1929, 11.

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 “Crowd Astonished by Connie Mack, New York Times, October 15, 1929, 33.

15 Frank Getty, “Cardinals Plan to Check Defeat,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Mirror, October 4, 1930, 4.

16 “Shores Praises Mack,” Syracuse Herald, January 5, 1931, 20.

17 The Sporting News, February 19, 1931, 5.

18 The Sporting News, March 12, 1931, 6.

19 “Blues Beat Colonels in 10 Innings, 3-2,” Evening Tribune, Albert Lea, Minnesota, August 28, 1933, 9.

20 The Sporting News, November 12, 1936, 2.

21 The Sporting News, June 8, 1938, 3.

Full Name

William David Shores

Born

May 26, 1904 at Abilene, TX (USA)

Died

February 19, 1984 at Purcell, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.