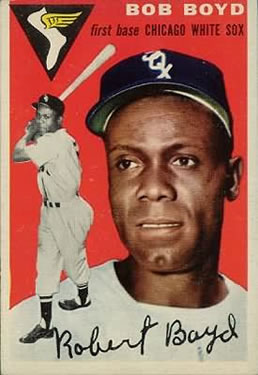

Bob Boyd

Even in a wheelchair, he obviously is an athlete. He strokes the wheels with controlled, fluid movements that make progress appear effortless. His smile is quick, his eyes eager. Time has generously sprinkled silver and gray over once black hair. But it still hasn’t erased all traces of his native Potts Camp, Mississippi, from his speech even though he’s widely traveled and has lived in the Midwest for four decades.

Even in a wheelchair, he obviously is an athlete. He strokes the wheels with controlled, fluid movements that make progress appear effortless. His smile is quick, his eyes eager. Time has generously sprinkled silver and gray over once black hair. But it still hasn’t erased all traces of his native Potts Camp, Mississippi, from his speech even though he’s widely traveled and has lived in the Midwest for four decades.

When he played first base for the Baltimore Orioles, they called him “Rope” or the Spanish version he picked up in winter ball, “El Ropo.” Some coach once pulled a short piece of it from his pocket to show how Bobby Boyd hit the ball. He rarely hit one for distance. But he hit baseballs often and very, very hard, usually on a trajectory about like that of a rifle bullet. Coupled with speed that as a freshman in high school propelled him 100 yards in 10 seconds, he was tough on pitchers, catchers and defenses.

Losing that kind of speed was bound to have been difficult. But it was nothing compared with losing one of the legs that made it possible. Long after his retirement as a driver for the Wichita, Kansas, bus system, Boyd was diagnosed with diabetes. “They told me they would have to cut off both of ’em right here,” he said, laying the knife edges of his hands across his legs just above the knees.

“But by the time they got through, they only took this one [the right],” he explained. “I’ve got a prosthesis and I get around pretty well. But when I’m home or working an autograph show, I use the wheelchair.

“If it wasn’t for this leg, well, I’d still be playing, the old-timers’ games, you know,” he continues. He obviously means it. From the pictures on the wall of his military-neat family room to the scrapbooks in the living room drawer, it’s apparent Bobby’s love for baseball never grew weak.

His home in Wichita is about half a mile north of sparkling Eck Stadium at Wichita State University. He can plainly see the lights at night from his house if he chooses or, frequently, from a seat in the stands. He’s a fixture at the collegiate games and those of the Wichita Wranglers of the Texas League where he likes to talk about the game with the youngsters. Even 40 years since he last played, he remains an interested and well-informed fan, only slightly chagrined that early 21st century players know little about what’s gone before them, particularly the struggles of pioneer black players.

In 1950 he was the first black man to sign with the Chicago White Sox and among the first with any major league organization. His career began when he was spirited out of Memphis to the Sox’ farm club in Colorado Springs on a 12:30 a.m. flight.

He wasn’t kidnapped, but his sale did set off a family feud among three brothers named Martin, all of whom were doctors. One, a dentist, ran the Memphis Red Sox where Bobby was playing. Another, a physician, owned the stadium where the Red Sox played and laid claim to owning the Sox as well as a rival team. The third, also a physician, was president of the Negro American League.

Dr. B. B. Martin, general manager of the Red Sox, made the deal with Frank Lane of the Chicago White Sox to part with Boyd for $15,000, Bobby remembers. Dr. Martin whisked Bobby to the airport, put him on the plane for Colorado and apparently breathed easily for the first time since the contract was signed.

“They gave me $500 and put me on the plane. The first time I ever flew. And when I got to Colorado Springs, some white dude met me and put me up at his house,” Boyd recalls. Still, Bobby, an admitted sleep lover, went right to work for the Sox’ Class A Western League affiliate, hitting a home run in his first time at bat and getting two other hits in five tries after the all-night flight.

Then Boyd found himself at the center of a family feud. Dr. W. S. Martin, the physician-brother who was bankrolling the Memphis team, learned of Boyd’s sale. He immediately ordered his attorney, Charles C. Crabtree, to sue the White Sox for $35,000, alleging the team had “lured” Bobby away. The suit was dismissed when the Martin brothers agreed to split the $15,000 sale price. Unruffled, Boyd hit .373 at Colorado Springs.

Robert Richard Boyd’s quest for baseball stardom started early. Potts Camp, where he was born October 1, 1925, just 60 years after the Civil War, is a town of 500 near the Tippah River in northern Mississippi. Sixty miles south and east lies Tupelo, Elvis Presley’s birthplace. The same distance north and west is Memphis, Elvis’s final hometown and the region’s metropolitan center.

Willie Boyd, Bobby’s dad, was “a cook — a chef,” he says. On weekends, Willie and his brother would put Bobby and his little brother Jimmy on the back of a truck with no bed to travel to baseball games where the two men played. As Bobby came of baseball age, dad saw to it that his left-handed son was a first baseman. Nothing else.

It was in Mississippi and later in Memphis that Bobby developed the smooth swing that would lead to a .327 batting average in what he adds up to 4,337 Negro, minor and major league times at bat. Often having no regulation ball, he made his own, wrapping crumpled paper with string, throwing it into the air and swinging at it with a stick. “I must have done that a million, maybe two million times,” he says. But each swing of the stick led him closer to the big leagues.

When Willie and Bobby’s mom, Bertha, separated, Bob stayed with her in Mississippi while his dad went to Memphis. That arrangement ended when Bertha died shortly after Bobby’s thirteenth birthday. For the last time, he left his classes at New Albany, Mississippi, High School and went to Memphis to live with his dad and go to work.

Still, baseball continued to dominate the youngster’s life even though he had no thought of playing in the major leagues. “We just didn’t believe that was something that could happen, you know,” he says now. “And we accepted that.”

World War II took Bobby from home. He went into the Quartermaster Corps and served two years. Freed from the service in 1947, he went to work in a United warehouse, but also decided to give baseball a serious try. He “walked on” to the Memphis Red Sox, a Negro American League team, where for $175 a month he had what amounted to an unlimited bus ticket. The team traveled and partly lived in a bus as it played both league games and a barnstorming schedule over a generous part of the eastern United States.

Boyd was in Negro baseball until 1950, never hitting under .352, playing in two East-West all-star games and leading the league in hitting in 1947. By his final season he was earning $500 a month and selling beer in the off-season.

He also met Valca. In 1947 he jammed his foot into a bag while stealing a base, injured his ankle and was taken to a hospital owned by the same Dr. Martin who later tried to block his sale to the White Sox.

Lying on a treatment table, Bobby saw a pretty student nurse go by and asked — demanded, really — to meet her. The romance culminated in the couple’s 50th wedding anniversary in 2002, celebrated at the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City.

It was a White Sox scout, John Donaldson, who arranged for Boyd to leave Memphis. “He was traveling on the bus with us, but I didn’t know who he was or that he was watching me,” Bobby says. “We all knew Jackie had signed, but we expected it to be a long time before any of the rest of us got to go.”

One member of the Red Sox did precede Bobby. Dan Bankhead, a pitcher, was signed by the Dodgers and appeared late in 1947, the year Robinson became the trailblazer and Larry Doby began playing for Cleveland.

“They were very careful of who they signed,” Boyd says. “They wanted people who would get along, who wouldn’t be too bothered if there were problems. Fortunately, I didn’t have very many. When I played at Houston in the Texas League, I was the first black player there, but no one made much of it.

“If there was trouble anyplace, it was verbal. Sometimes somebody at Colorado Springs or Houston or Beaumont would yell ‘nigger’ or something like that. But usually we just played ball.”

Still, he was performing in a highly segregated society. “We were barnstorming through the South with the Cardinals when I was with Chicago,” he continues. “They had one black player and Minnie Minoso and I were rooming together. While we were in the South they assigned us bodyguards. Of course, we couldn’t stay in the hotels with the white players, so they arranged rooms for us in the homes of local people. Those bodyguards would sit up and sleep on the front porches. During the games they’d be in the dugouts with us. Maybe they were the reason, but we were never bothered.”

Strangely, Bobby felt he owed his major league career to Paul Richards, the Texas-born manager he believes may have been the most prejudiced against blacks of any he encountered.

Boyd never quite made it with the White Sox, bouncing back and forth from the minors to Chicago. Always someone like Eddie Robinson or Ferris Fain was in the way. After Colorado Springs, Bobby hit .342 in the Pacific Coast League before playing his first dozen games with Chicago in September, 1951. Sent back to Seattle for 1952, he hit a league-leading .320 and stole 33 bases. That same year he led the Winter League in Puerto Rico in hitting, giving him two league batting titles for the year.

But he was still stuck in the minors, first Charleston then Toronto in 1953. Over the course of 14 years in organized baseball, he played in Colorado Springs, Sacramento, Seattle, Charleston, Toronto, Houston, Oklahoma City, Louisville and San Antonio as well as for Winter League teams in Puerto Rico and Cuba. “I spent a lot more time in the minors than I thought I would or that I wanted to,” he explains. Even in 1953, after hitting .297 for one-third of a season in Chicago, he was demoted to the minor leagues, where he languished until Richards rescued him.

Richards had been the White Sox manager and remembered Bobby’s potential when he took over at Baltimore. He had the Birds draft Boyd from Houston in the Texas League, where he had gone reluctantly after the Cardinals obtained him from Chicago. Boyd was Richards’ only draft choice in 1956.

“He would say a lot of things in the locker room about blacks and things like that,” Boyd remembers. “But he let me play and was helpful to me.” Actually, figuring out that Bobby should play didn’t demand a doctorate in baseball. In 1957, his breakout year, Boyd was fourth in American League hitting behind Ted Williams, Mickey Mantle, and Gene Woodling with an average of .318. He also was the first modern Oriole to hit over .300 for an entire season.

If Bobby lacked any physical attribute, it was height. With thick socks he reached 5′ 10″. For a first baseman that’s undersized. At Houston, for perhaps the only time in Boyd’s career, manager Dixie Walker openly questioned his defensive ability by telling a reporter for The Sporting News that Bobby’s shortness hurt him in stretching for throws.

But no one else was concerned, Richards in particular. After watching him work out, he also talked with a reporter for The Sporting News. “Boyd can really handle that mitt around first base. I know he’s good enough defensively for the big leagues and he has real speed,” he said.

The numbers all side with Richards. As the shortest first baseman in the majors in 1957, Boyd led the league in putouts with 1,073 and his .991 was the third best fielding percentage among American League regulars. Only Earl Torgeson, who made just one error for a remarkable .999 average, and Bill Skowron, who fielded .992, did better. Torgeson was the league’s tallest first baseman. Boyd and Skowron were the shortest.

Bobby even started a triple play at Baltimore. According to the New York Times, with two men on, the Senators’ Eddie Fitzgerald hit a line drive down the first base line that Boyd caught. He threw to shortstop Chico Carrasquel, who stepped on second for the second out, then threw back to Boyd, who tagged first for the third.

Boyd did play in the outfield at times, and one 1956 experiment there almost ended in disaster. Boyd remembers fielding a hit off the bat of Cleveland’s Jim Hegan, a catcher who may have been the slowest runner in the league. Seeing him continue to run past first, “I was determined he wouldn’t get to second on me,” Boyd continues. “So I threw just as hard as I could.” The throw put so much pressure on his arm that it broke, leading to two surgeries and a long recovery.

Boyd’s relatively small size also could have affected his power output. In his best major league season, Boyd hit only seven home runs and had a total of just 19 in 1,936 major league games. But he made up for that in part with speed. He hit 23 triples and 81 doubles as well.

Line drive singles were the major product of his work, the “frozen ropes” that led to his nickname. In the book When the Cheering Stops, Bobby remembered, “Luman Harris, who was Paul Richards’ pitching coach, was the first guy who called me that. See, I was never a long-ball hitter, but I could really hit line drives. So one day during spring training, Harris cut off a piece of rope and put it in his pocket. He was looking at me after I hit another line drive and he pulled the rope out and held it in the air. ‘Rope’ was all he said to me and the nickname stuck. In fact, when I see some of the guys today, they still laugh and call me ‘The Rope.’”

Sometimes he was “El Ropo.” Bobby also played in the Spanish-dominated Winter Leagues and was as tough on pitchers there as he was in the minor and major leaguers. He was in Cuba when he learned he had been given a real shot at the majors. Valca had to awaken him to let him know the Orioles had purchased his contract from Houston, where he had hit .321 and .309 over two seasons before Richards had rescued him.

In five seasons at Baltimore, all after his 30th birthday, he responded with averages above .300 four times. The one miss was a summer he was ill from a chronic ulcer that wasn’t cured until after he left organized baseball.

In 1960 the Orioles came up with a power-hitting first baseman, Jim Gentile, and Bobby was relegated to pinch-hit duty. He was traded to the Kansas City A’s, who had Norm Siebern at first. Norm was having a good year in 1961. Bobby did not, hitting .229 in 26 games. Then he went to Milwaukee for his only look at the National League. There he batted .244 in 36 games.

He spent two more years trying. At Louisville and Oklahoma City in the American Association he regained his batting eye, moving about .300 again. But he won no return call to the major leagues and retired after the 1963 season.

Boyd was still a ballplayer, so instead of abandoning the game he moved to Wichita, where the local bus company had put together a baseball team to compete for the national semipro championship. Called the Dreamliners for the buses they drove, the club had three former major league players on its roster. Boyd, former Brave Jim Pendleton and Tom Borland, who had pitched briefly at Houston and for the Red Sox, were joined by several former minor league standouts. For the next four seasons, until well after his 40th birthday, Boyd anchored the Dreamliner infield, hitting as much as .500 in some seasons.

And life was good. “The most I ever made in one major league season was $18,500,” he continues. “I was making as much as I had been in the majors between my job driving a bus and playing baseball.” And after that part of the good life ended, the Boyds stayed in Wichita where Bobby continued to drive a bus for 20 years.

He remembers Negro baseball with fondness. He has been active in the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City and has his own favorites among former opponents from his days in Memphis. In 1951 he gave The Sporting News this list of all-stars made up of those he played against: Don Newcombe, pitcher; Roy Campanella, catcher; Jackie Robinson, first base; Ray Dandridge, second base; Hank Thompson, third base; Willie Wells Sr., shortstop, and Larry Doby, Willie Mays and Sam Jethroe, outfielders.

“The players in the black leagues were major league quality players,” he declares. “I don’t mean double-A or triple-A, but major league. Guys like these were playing when I was along with several others who by then were too old to have a chance at the majors.”

Black teams did play a bit differently. In an interview with Edgar Munzel published in The Sporting News, Bobby said, “The white leagues play it more strict. They do things more according to the book. In the Negro leagues the player does more what he feels like doing.”

His version of “doing what he feels like doing” was swinging at pitches outside the strike zone. Bobby believes he hit bad pitches better than strikes. Once he swung at a third strike thrown by one-time teammate Hoyt Wilhelm. The ball hit Boyd on the foot, fanning him on a pitch that should have sent him to first. “I really hated the knuckleball,” Boyd says. He still shakes his head half a century later.

He is quick to say the toughest pitcher he faced in the major leagues was Herb Score before an injury ended the Cleveland star’s career. Both the Indians and New York had pitching staffs that offered little respite. “They both had four outstanding pitchers. The others would always have a couple, but the Indians and Yankees had four. There just wasn’t any time to relax.” Allie Reynolds, Vic Raschi, Ed Lopat and Whitey Ford were New York’s front four. The Indians had Bob Feller, Bob Lemon, Early Wynn and Mike Garcia with Score finally taking over as staff fireballer from Feller.

Ted Williams is the best hitter Boyd remembers. In When the Cheering Stops, he recalled a ball hit by Williams that struck the first base bag so hard it broke the leather strap holding it to the ground, sending it careering to Boyd, who was playing deep behind it. “I just laughed like hell at that one,” he says.

The young Mickey Mantle was the best player he remembered. He was particularly dazzled by the Yankee outfielder’s speed. Boyd, of course, had speed of his own, and often used it to bunt for hits, but said he needed work on dragging the ball. Mantle could bunt or hit home runs. Willie Mays and Henry Aaron are the other two men he rates as the best players he ever saw.

After all the games and all the memories, Bobby did some scouting for the Orioles. He and Valca brought up their daughter, Deborah James, who teaches at a school not far from the Boyd home; their grandson, Bryan James, was an outfielder for Nicholls State University at this writing. The other two grandchildren live in Wichita. Kimberly Knox, like her mother, teaches school. Patrick James still attends one.

On September 7, 2004, Bobby Boyd died after a long battle with cancer. His funeral services were held on September 12. His lifelong spirit probably was captured well in a 1957 Sporting News article quoting Baltimore’s Richards: “How are you going to get El Ropo out of there? It’s almost impossible. Boyd comes to play.”

Sources

Unless otherwise attributed, material comes from interviews with Bobby and Valca Boyd, February 2003.

The Sporting News, July 31, 1950; August 16, 1950; September 27, 1950; March 14, 1951; June 15, 1955; July 31, 1957.

The New York Times, April 10, 1959

The KBA News, July 1997

Lee Neiman, Dave Weiner, Bill Gutman, When the Cheering Stops, Macmillan Publishing Company (1990)

Jeannine Bucek, ed. director, The Baseball Encyclopedia, 10th edition, Macmillan Publishing company (1996)

The Wichita Eagle, July 1964

Full Name

Robert Richard Boyd

Born

October 1, 1919 at Potts Camp, MS (USA)

Died

September 7, 2004 at Wichita, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.