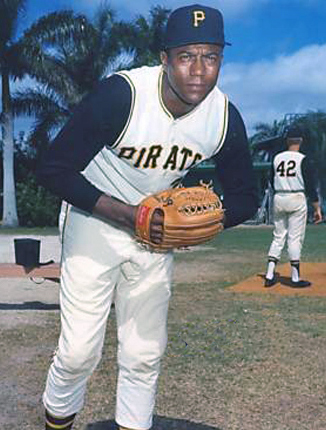

Bob Veale

Bob Veale was one of the hardest-throwing and most intimidating strikeout pitchers in the National League from 1962 through 1972. The bespectacled left-hander stood 6-feet-6 inches tall and weighed 212 pounds — the combination of size, arm strength, and questionable vision made him an imposing figure on the mound and one of the most difficult pitchers to hit in his era. During his tenure with the Pittsburgh Pirates, Veale struck out 1,652 batters, second only to Bob Friend for the team record. He led the National League with 250 strikeouts in 1964, edging out Bob Gibson, and struck out a career-high 276 in 1965, only to finish a distant second to Sandy Koufax. He won a world championship ring with the Pirates in 1971, and on September 1 of that year he played in the first major-league game started by an all-minority lineup, entering the game in relief. He was sold to the Boston Red Sox in 1972, and pitched for them for three seasons. He finished with 120 wins and a career ERA of 3.07, better than the league average, and a strikeouts-per-nine-innings ratio of 7.96, which as of 2014 was a Pirates team record.

Robert Andrew Veale was born on October 28, 1935, in Birmingham, Alabama, to Robert Andrew Veale Sr. and Ollie Belle (Ushry) Veale, the second of their 14 children, and one of their largest — he came into the world at 13 pounds, 4 ounces. His father pitched for a short time for the Homestead Grays of the Negro National League. He worked for the Tennessee Coal and Iron Company, a subsidiary of US Steel that was Birmingham’s largest employer at the time. Young Veale played on the sandlots of Birmingham with both blacks and whites. “We didn’t know we were breaking segregation laws,” he said. “We just thought we were playing baseball. I had white friends, kids I played ball with all the time. We weren’t thinking about integrating anything. We were just playing ball.”1 As a youngster he excelled in both baseball and basketball. Winfield Welch, manager of the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League from 1942 to 1945 and coach of the Harlem Globetrotters, wanted young Veale for his traveling basketball team, but Veale’s father would not agree to it.

At 12 Veale played for the 24th Street Red Sox in the Birmingham Industrial League, and worked the concession stand at Rickwood Field, home to the Black Barons and the Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association. “I used to run change around to the different concession stands, anything to make a coin,” he said.2 Veale used to chase foul balls and home runs at Rickwood and then sell the balls back to the Black Barons or the visiting team. Eventually player-manager Piper Davis made him the batboy and let him pitch batting practice regularly. “I used to pitch batting practice for the white Barons and come back and do the same for the Black Barons,” Veale said. “When the game started I went to the concession stands and did the things I normally did.”3

In 1948, the youngster Veale occasionally pitched batting practice and then watched as the Black Barons — featuring 17-year-old Willie Mays in the outfield — went on to win 63 games and beat out the Kansas City Monarchs for the Negro American League pennant. The Black Barons lost to the Homestead Grays in a five-game Negro League World Series, the last of its kind.4 By 1950 Mays had been signed by the New York Giants and was on his way to a Hall of Fame career, and Veale — burning with ambition to get out of Birmingham — wanted to pitch against him one day. Hustling for money by hanging around the Negro Leagues no longer held its appeal. “You go someplace, they gonna give you a dollar to play and a dollar for meal money,” Veale said. “But a growing kid need more than that.”5

The Black Barons had a longstanding rivalry with the Kansas City Monarchs, and Monarchs manager Buck O’Neil had seen Veale pitch at Rickwood Field. While Veale attended Holy Family High School in the Ensley neighborhood. Monarchs owner Tom Baird repeatedly tried to sign Veale for his team. After the integration of the sport, Baird had realized that the future of baseball for an owner of a Negro League team was channeling talent to Organized Baseball. He wrote to the Veale family in November 1954 and again in June 1955, after Veale left Birmingham to attend Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas, on an athletic scholarship. In the second letter, Baird suggested that the father and son had agreed that Bob would sign with the Monarchs during a conversation with O’Neil in May of 1955. The Veales felt they were being coerced. “Buck O’Neil and all those guys were demagogues,” Veale said. “They were out for their own personal gain, one way or another, for financial and prestigious gain, or whatever they were seeking at the expense of others. I didn’t think it was too businesslike or too compassionate.”6

Veale played baseball and basketball in college, and by 1958, when he was a senior, he was well known to scouts. In May of that year he was invited to try out for the Cardinals in St. Louis. Unbeknownst to the host team, Pirates scout Tuffie Hashem was in attendance early that day, and watched Veale warm up. Buddy Hancken, the Pirates’ scout in Birmingham, who had been following Veale for years, seconded Hashem’s recommendation, and Veale auditioned for general manager Joe L. Brown and pitching coach Bill Burwell at Wrigley Field in Chicago, where the Pirates were playing. They signed Veale that day.

At the age of 22, Veale was dispatched to San Jose of the Class C-California League. About the same time the team was transferred to Las Vegas. In 17 games (eight starts), he was 2-6 with an earned-run average of 5.43. The following year at Wilson of the Class-B Carolina League, he became a starting pitcher. In 147 innings he gave only one home run and led the league with 187 strikeouts. On July 23, 1959, he pitched a 2-0 no-hitter against Raleigh. He completed the year with a 12-5 record and an ERA of 3.49, and was advanced three levels to Columbus of the Triple-A International League for the 1960 season.

During his time in North Carolina, Veale experienced the worst treatment of his career as a result of the racism that was prevalent in the South during the period. While the harassment was constant, Veale did not let it bother him. “To me, it was just funny,” he said. “I grew up in Alabama and got used to hearing stuff like that. It was just another stepping stone to success, I guess. Those remarks just made you work harder to achieve the goals that you had in sight.”7

Veale spent three seasons with Columbus. In 1960 he led the league in walks allowed, with 119 in 172 innings. He won 10 of 19 decisions and finished with an ERA of 3.51. Veale established himself as a genuine prospect the following year. In 201 innings he struck out a league-leading and team-record 208 batters, and cut his walks down to 92.

The Pirates were suitably impressed, and invited Veale to spring training in Fort Myers, Florida, in 1961. While the white players stayed at the Bradford Hotel, the black players were placed with host families in the black neighborhood. Veale grew up with segregation, and he did not dispute the circumstances. In some ways, he preferred staying with the Evans family in Fort Myers. “Boy, you’d have the finest cooks you’d ever want to meet,” he said. “We ate much better than the white players at the Bradford Hotel. I couldn’t wait to leave the ballpark and get home and eat dinner.”8 Sent back to Columbus, he won 14 games and lost 11 with a 2.55 ERA and only 92 walks in 201 innings pitched.

Veale stuck with the Pirates in 1962 and made his major-league debut on April 16, starting against the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field. He lasted only 2⅓ innings, allowing three earned runs on six hits and three walks. He got his first win in his next start, on April 26 in Pittsburgh when he pitched a complete game to defeat the New York Mets, 4-3, and give the Pirates their record-tying 10th consecutive victory to start the season. Veale failed to make it through the fourth inning in his next two starts, and was moved to the bullpen, where he pitched four times through May 25, when he was sent back to Columbus. On August 10 he set an International League record for the most strikeouts in a game, 22 against the Buffalo Bisons. Veale didn’t get the win; he was lifted for a pinch-hitter in the top of the 10th inning. He suffered an even worse fate on September 3, when he pitched a one-hitter against Jacksonville and struck out 15, only to lose 2-1. After winning eight games and striking out 179 in 134 innings, Veale and his good friend Willie Stargell were called up to the Pirates in September. On September 20 against the Cincinnati Reds, he pitched into the seventh inning in a 4-3 win. He followed that with a three-hit win over Milwaukee on the 28th, and earned his first save two days later.

Manager Danny Murtaugh began the 1963 season intending to use Veale out of the bullpen, preferably to face only one left-handed batter or in a mop-up role. After his first two appearances, Veale appeared in 10 games before a stretch of 15 straight Pirates losses, despite an ERA of 0.70 in relief. On August 25 the Pirates put Veale back in the starting rotation. He shut out the Phillies for seven innings, but the Pirates lost in the 11th when Johnny Callison hit a two-run home run off Elroy Face. Veale was sensational in September; in six starts, he threw three complete games, two of them shutouts, and finished with an ERA of 1.20 for the month.

Veale made his first start in 1964 against the Chicago Cubs, allowing four earned runs over seven innings in an 8-4 loss. He earned his first victory of the year two starts later with a complete game against the Mets. On the evening of June 7 against the Houston Colt .45’s, he needed only seven innings to strike out 12 batters, tying the team record for most strikeouts in a nine-inning game set by Babe Adams in 1909. He not only failed to record the record-breaking strikeout, but he also lost the Pirates’ 3-1 lead in the final frame, as the Colt .45’s tied the game on two-strike hits by both Mike White and Walter Bond. “Yes, I knew I had tied the record,” Veale said. “But I’m angry at myself for not finishing. It was all my fault.”9

Two starts later, on June 16, Veale duplicated his feat, striking out 12 New York Mets in a complete-game, 6-4 victory. Adams’ record finally fell on September 22 when Veale fanned 15 Milwaukee Braves, but it was not a happy occasion as he pitched a complete game only to lose 2-0.

Veale definitely paid attention to his strikeouts. Heading into the last day of the 1964 season, he had 245, and felt he was comfortably ahead of Bob Gibson for the league title. In the clubhouse he heard Harry Caray announce on the radio that Gibson was warming up in the bullpen for St. Louis against the Mets in New York. Veale requested three innings of work, and recorded five strikeouts, for a total of 250. Had he not pitched, he would have finished in a tie with Gibson. He concluded the season with a record of 18-12 and an ERA of 2.74. He reportedly received the largest pay increase of the team for the next season.

In 1965 Veale finished with a record of 17-12 and an ERA of 2.84. He pushed his strikeouts to 276, the most in the modern era by a Pirate. Led by Veale on the mound and Stargell and Roberto Clemente at the plate, the Pirates finished with a record of 90-72, good enough for third place in the National League, seven games behind the pennant-winning Los Angeles Dodgers.

One of the highlights of Veale’s campaign took place on June 1 in Pittsburgh, when he pitched a five-hit shutout of the Philadelphia Phillies to give the Pirates their 12th straight victory, while striking out 16 batters to break his own team record. The game was interrupted twice for long periods due to rain, forcing Veale to warm up on three separate occasions. “I watched him warm up three times,” said Phillies pitcher Chris Short, “and I swear he got faster every time.”10 On September 19, 1966, Veale pitched a 10-inning, one-hit shutout against the Phillies in Pittsburgh, striking out 12 batters. “It had to be the best game I ever pitched in the majors,” he said. “I never had a one-hitter before and never felt as confident in my pitches.”11

With an outfield consisting of Willie Stargell, Roberto Clemente, and Matty Alou, the Pirates made a serious run at the National League pennant in 1966, finishing with a record of 92-70 that left them only three games behind the Los Angeles Dodgers. Despite a sore back that flared up from time to time, Veale was a workhorse once again, starting 37 games and finishing 12 while posting a 16-12 record and an ERA of 3.02. One of his best efforts came on June 19, 1966 when he pitched an 11-inning complete game against the Atlanta Braves, allowing only five hits while striking out nine. “No man should lose if he can pitch the way Veale did that day,” said Stargell, who won the game with a home run in the final inning. “Why, I could see the blue flame rising from his fastball way out in left field.”12 The game fell on Father’s Day, leading Veale to speak of his father after his performance. “My dad would have been proud of me had he been there to see the game,” he said. 13

In 1967 Veale started fast, winning his first six starts and seven of his first eight. Accolades from opposing hitters continued to pile up, with predictions of a 20-win season. “Over the first four innings in his second game against us, Veale was faster than I’ve ever seen Koufax,” said Lou Brock.14 But by the end of a campaign that saw the Pirates finish a disappointing 81-81, Veale once again had 16 victories, but with an elevated ERA of 3.64 and only six complete games.

During the 1968 season, the nagging injuries to his back and shoulder gave way to a more serious elbow problem. After a shutout against the Cardinals in which he struck out 13 batters, Veale admitted to having pitched through elbow pain throughout the game. “My elbow was hurting me all through the game,” he said. “I wanted to get out of each inning in a hurry. I don’t believe in overpowering the batter anymore. I find when I try to cut loose I feel a dull ache in my elbow.”15

Despite the injury, 1968 was a good season for the left-handed ace, but the numbers support the change he was forced to adopt. Both his strikeout and walk rates were significantly reduced, suggesting that Veale was attempting to pitch to contact more often. The Pirates finished at 80-82 for the year – Veale’s own record of 13-14 was a reflection of the disappointing campaign.

Over the next two seasons, Veale maintained his usual workload of 200-plus innings, and the Pirates won 88 and 89 games respectively, but he finished with a losing record in both years. His ERA rose to 3.92 in 1970, and prior to the 1971 campaign there were rumors that the Pirates were looking to trade him. Danny Murtaugh, who returned to manage the club in 1970, instead switched Veale to the bullpen.

The 1971 season turned to be one of the greatest in the history of the franchise. Under Danny Murtaugh, the Pirates won the Eastern Division title with 97 victories, then defeated the San Francisco Giants three games to one in the NLCS. In an epic World Series, the Pirates defeated the Baltimore Orioles in seven games.

Veale pitched in 37 games out the bullpen, but despite finishing with a record of 6-0, his ERA was a very high 6.99. He did come on strong in September as the Pirates made their push for the division title, allowing only one run and two hits in his last 7⅔ innings. He made only one postseason appearance, however, in Game Two of the World Series. He faced five batters, allowing two inherited runners to score on two walks and one hit, as the Orioles won, 11-3.

On September 1, 1971, the Pirates became the first major-league team to start a lineup of all minorities. Veale entered the game in the third inning in relief of starter Dock Ellis, and struck out the only batter he faced. Many of the players on the team realized what was about to take place when they first saw the lineup card, while others didn’t realize what was happening until the game was under way. At one point, Dave Cash exclaimed to Al Oliver, “Scoop, we got all brothers out there!”16 Rather than cause dissension, the event brought an already friendly, loose bunch of players even closer together. “I think it was a great thing that happened there,” said Bob Robertson, who was replaced by Al Oliver in the starting lineup of the historic game. “That was the type of ballclub we had. It didn’t make a difference if you were black, yellow, green, purple, whatever. We got along fine. We enjoyed each other’s company. We had a lot of respect for one another. I thought that was a great evening, to see that.”17

While the 1971 season ended with a World Series ring, Veale, now 36 years old, realized that his time with the Pirates was probably nearing the end. Still, the team protected him on the 40-man roster. “I’d like to stay in Pittsburgh,” he said. “But if I don’t, I won’t quit. I still think I can help some club. Why is it that so many people feel you’re through when you pass 35?”18

Veale pitched well in his first three outings to begin the 1972 season, but was hit hard in his next two appearances, and the Pirates, needing a roster spot, placed him on waivers. On May 10 he was released. “I knew it was coming,” he said. “I always wondered how it would feel, the moment like this. It’s kinda harsh, you know.”19 Manager Bill Virdon delivered the message. “It wasn’t an easy thing to do,” he said. “Everybody liked Bob. He was a good man around a ballclub. Never a problem. Veale wasn’t that kind of a person.”20

Veale cleared waivers and agreed to accept an assignment to the Pirates’ Triple-A farm club in Charleston. He appeared in 17 games for the Charlies, including 12 starts, and finished with a 2.82 ERA and 76 strikeouts in 83 innings of work. On September 1, upon the recommendation of Danny Murtaugh, the Boston Red Sox signed Veale. He made his first appearance in the American League on September 10, and pitched extremely well, allowing only two hits and no runs in eight innings. The Red Sox pennant run fell short, but the club would bring him back in 1973.

Veale married his high-school sweetheart, Eredean Sanders of Graysville, Alabama, in February of 1973. He married later in life than many of his teammates; while he never made much of it, he had been waiting until he helped all 13 of his siblings attend college. Veale pointed out the problem of mixing baseball and marriage: “You’ve got to have a real fine, tolerant wife — one who understands the problems of baseball. If you’re not fortunate enough to get the right one, she can pull you down. But, thank God, I’ve got the right one.”21

Veale had a comeback season for the Red Sox, making 32 relief appearances and earning 11 saves. At the end of the year, the team released him but invited him to return to spring training in 1974 on a minor-league contract. Under the rule in place at the time, Veale could not be added to the Red Sox 25-man roster until May 15, so he began the season with Triple-A Pawtucket. There he pitched as well as served as a coach. While warming up on the night before he was scheduled to rejoin the Red Sox, he heard a pop in his shoulder and experienced enough pain that he could not lift his left arm the following morning.

The Red Sox training staff worked on Veale’s arm throughout the year, and he was able to appear in 18 games. But as the season progressed, he was used sparingly, pitching only 13 innings, with an ERA of 5.54. His last major-league appearance came on September 8 against the Milwaukee Brewers. Once the season was over, he made it known that he would like to stay in baseball as a coach or minor-league instructor, and while he had to sit out the 1975 season, he was hired in 1976 by the Atlanta Braves as a minor-league pitching instructor.

On his way to the Braves’ West Palm Beach spring training camp in February of 1977, Veale drove his car into a canal when he became drowsy from medication he had taken for the flu. “Believe me, I’m lucky,” he said. “Two feet either side of where I went into and I’d have hit a concrete culvert head-on.”22 Despite his scare, Veale enjoyed his new job. “I love it,” he said. “Actually, it’s more challenging than playing. There’s great satisfaction in being in a position to move young fellows up to the major leagues. That’s what life is all about.”23

Veale went on to work for New York Yankees in the same capacity, and in 1983 he was hired as pitching coach of the Utica Blue Sox, an independent team playing in the affiliated New York-Penn League. On “Bob Veale Day,” the Blue Sox celebrated his career, and Willie Stargell flew in for the occasion. Stargell commented, “There are givers and there are takers in the world. Bob Veale is a giver.”24

Veale had always maintained his offseason home in Birmingham, and after his retirement from baseball he returned there to stay. At the age of 58, Veale stayed connected to his baseball roots by working as a groundskeeper at Rickwood Field two days a week. He played an important role in preserving the storied old ballpark he played in as a child.

Veale was always well-liked by his teammates and trusted by his managers. Danny Murtaugh selected him to be his enforcer. “Anytime anyone got in trouble, I had to go get ’em,” said Veale. Murtaugh would send me because he knew I would bring them back.”25

Considering that he was perennially among the league leaders in walks, and was perhaps the hardest throwing left-handed pitcher in baseball, hitters were naturally reluctant to dig in against Veale. Manny Sanguillen said, “Lou Brock was a little scared of Veale sometimes because Bob was nearsighted and would take off his glasses and pitch anyway. Willie McCovey, too. One day, Bob took those glasses off and threw the ball 100 miles per hour at McCovey. I asked Veale what happened, and he said, ‘My glasses were too wet, and I wanted to show him I could throw a strike without my glasses.’ That pitch was ten feet high.”26

As fearsome as he was on the mound, Veale did not have a mean streak. “He can throw the ball through a brick wall, but everybody knew that he was a gentle giant,” said teammate Gene Clines. “If Veale would knock you down, it had to be a mistake. He didn’t want to hurt anybody.” 27

Veale did not begrudge current players the high salaries they achieved after he left baseball. “I should have been born in 1955 instead of 1935,” he was quoted as saying in 2002. “But I don’t dwell on anything like that. It’s the foam at the bottom of the spillway. It’s water over the dam. Veale had one more claim to fame; it was rumored that he was the originator of the famous baseball oxymoron, “Good pitching can stop good hitting every time … and vice versa.” Author Allen Barra once approached Veale at Rickwood Field, where Veale was consulting on the production of the film Cobb. “I asked him, ‘Mr. Veale, are you the one who said ‘Good …’ He cut me off with ‘Yes, I am.’ ” 28

When he was a young boy facing adversity, Veale often remembered the words of his father. “My daddy said, ‘If you got what it takes, everything will work out.’”29 His ambition had been to follow Willie Mays to the big leagues. When he achieved his goal, he was named to two National League All-Star teams, in 1965 and 1966. Willie Mays led off both games for his team. “That was good advice from my daddy, said Veale.”30

In his later years, Bob Veale resided in Birmingham with his wife, Eredean. In 2006, he was inducted into the Alabama Sports Hall of Fame.

He died at the age of 89 on January 5, 2025.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also relied upon the following:

Bird, John T., The Bill Mazeroski Story (Birmingham, Alabama: Esmerelda Press, 1995).

Hall, Donald, Dock Ellis in the Country of Baseball (New York: Touchstone Books, 1989).

Markusen, Bruce, The Team That Changed Baseball: Roberto Clemente and the 1971 Pittsburgh Pirates (Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing, 2006).

Powell, Larry, The Black Barons of Birmingham: The South’s Greatest Negro League Team and Its Players (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009).

Notes

1 Allen Barra, Rickwood Field: A Century in America’s Oldest Ballpark (New York: W.W. Norton, 2014), 140.

2 John Klima, Willie’s Boys: The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, The Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend (Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley Publishing, 2009), 70.

3 Klima, 71.

4 Author Klima quotes Veale as saying that he pitched batting practice for the Barons. There is no suggestion in Willie’s Boys that Veale pitched in any league games at 12 years old.

5 Klima, 84.

6 Klima, 84.

7 Frank Garland, Willie Stargell: A Life in Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2013), 41.

8 Garland, 41.

9 Les Biederman, “Tying SO Record Hard to Swallow for Veale,” Pittsburgh Press, June 8, 1964.

10 Mark Mulvoy, “Baseball’s Week,” Sports Illustrated, June 14, 1965.

11 Les Biederman, “Bob Veale,” Pittsburgh Press, October 2, 1965.

12 Les Biederman, “Blue Flame Trails Each Veale Pitch,” Pittsburgh Press, July 9, 1966.

13 Biederman, “Blue Flame Trails Each Veale Pitch.”

14 Les Biederman, “Veale Ignores an Aching Back — Buc Lefty Making Hitters Moan,” The Sporting News, May 27, 1967.

15 Les Biederman, “Smokeless Bob Veale a Puzzle to Redbirds,” Pittsburgh Press, June 1, 1968.

16 Bruce Markusen, “Remembering the All-Black Lineup,” Bruce Markusen’s Cooperstown Confidential (blog), September 1, 2006 (8:50 a.m.), https://bruce.mlblogs.com/2006/09/01/remembering-the-all-black-lineup/.

17 Markusen.

18 Charley Feeney, “There’s Still Life at 36 for Veale in Pirate Bullpen,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 4, 1971.

19 Pat Livingston, “Bob Veale the Pirate: A Memory,” Pittsburgh Press, May 4, 1972.

20 Livingston, “Bob Veale the Pirate.”

21 Fred Ciampa, “Veale Another Coup for O’Donnell,” Boston Herald, April 22, 1973.

22 Pat Livingston, “Bang, Veale’s Back!,” Pittsburgh Press, March 4, 1977.

23 Livingston, “Bang, Veale’s Back!”

24 Scott Pitoniak, “Stargell, Veale Renew a Longtime Friendship,” Daily Press [Utica, New York], 1983.

25 Garland, 69.

26 Bird, 216.

27 Hall, 33.

28 Allan Barra, “My Most Favorable Baseball Moments,” Salon, July 26, 2002.

29 Klima, 85.

30 Klima, 85.

Full Name

Robert Andrew Veale

Born

October 28, 1935 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

Died

January 5, 2025 at Birmingham, AL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.