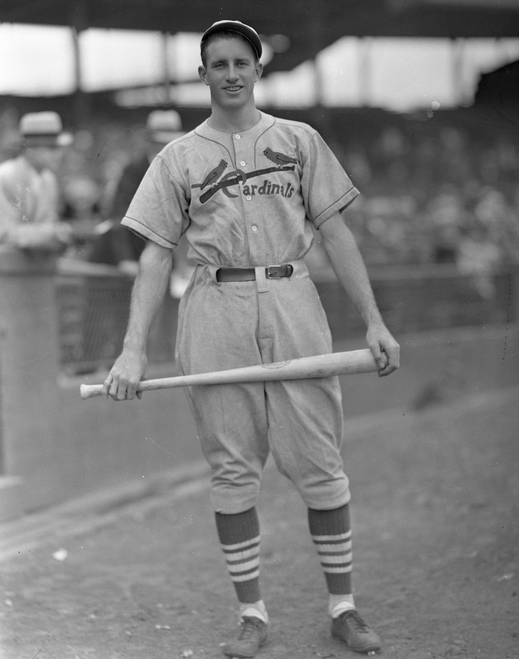

Burgess Whitehead

Burgess Urquhart Whitehead was a solid contributor to the success of the Gas House Gang in 1934, appearing in 100 games while spelling Leo Durocher at shortstop, Pepper Martin at third base, and Frankie Frisch at second. In his first full year in the big leagues, Whitehead had 332 official at-bats and hit a solid .277. He was relegated to the bench, however, in the epic seven-game World Series against the Detroit Tigers, appearing in only a single game as a late-inning pinch-runner and replacement at shortstop.

Burgess Urquhart Whitehead was a solid contributor to the success of the Gas House Gang in 1934, appearing in 100 games while spelling Leo Durocher at shortstop, Pepper Martin at third base, and Frankie Frisch at second. In his first full year in the big leagues, Whitehead had 332 official at-bats and hit a solid .277. He was relegated to the bench, however, in the epic seven-game World Series against the Detroit Tigers, appearing in only a single game as a late-inning pinch-runner and replacement at shortstop.

Whitehead was born on June 29, 1910, in Tarboro, North Carolina. His father was a dentist and tobacco farmer and shortly moved the family to Lewiston, North Carolina. Burgess, who was called Whitey, first attended Lewiston High School and then the Augusta Military Academy in Virginia, where he graduated in 1927 with the highest academic record of anyone who had attended the school in 75 years. He also batted .484 and .523 in his two years on the baseball team.1

He was a hot prospect but wanted a college education and enrolled at the University of North Carolina. After a season starring on the freshman team, he spent three weeks in the summer of 1928 working out with the New York Giants under the watchful eye of John McGraw and then two weeks with the Detroit Tigers. Both teams offered him contracts, but Whitehead opted to return to the University of North Carolina, where he became the varsity shortstop, playing alongside future big leaguer Lew Riggs.2

While at North Carolina Whitehead played semipro ball in Emporia, Virginia, for $35 a week and during the school year sold football tickets and worked in a dormitory laundry to earn spending money.3 Along the way, he continued to excel in the classroom, earning Phi Beta Kappa honors.

Burgess was named team captain before his senior year but was ruled ineligible when it was learned that he had signed a professional contract with the St. Louis Cardinals. He was assigned by the Cardinals to the Columbus (Ohio) Red Birds in the Double-A American Association. (At the time Double-A was the highest rung in the minor leagues.)4 Whitehead got off to a rough start in Columbus, however, and manager Nemo Leibold told him the club was going to release him. Whitehead then went to club president Larry MacPhail to receive his paperwork and travel money. MacPhail, however, noticed Burgess’s Phi Beta Kappa key hanging from his vest chain and decided a ballplayer with that kind of smarts deserved a longer look. So MacPhail explained to Leibold the significance of the key and further suggested that Whitehead might be more suited to second base than shortstop.5

It turned out to be a great move. Whitehead proceeded to hit .328 in 135 games for the fourth-place Red Birds. During a doubleheader against the Louisville Colonels he knocked out eight hits in nine at-bats6 and was later named to the American Association All-Star team.

The Cardinals had future Hall of Famer Frankie Frisch ensconced at second base so Whitehead was back with Columbus in 1932. Playing in 162 games with 675 official at-bats, he totaled 211 hits and batted .313 for the Red Birds, who rose to second place. The Cardinals invited Burgess to spring training in 1933 and he stuck with the club, beginning the season as a utility infielder, but after seeing sparse playing time was shipped back to Columbus.

There he became an integral part of one of the best minor-league teams of all time. The Red Birds swept to the American Association pennant by 15½ games, finishing with a 101-51 won-loss record.7 Whitehead played in 89 games and hit a resounding .346 to lead the team, before a late-season call back to the Cardinals.8 In limited action as a late-inning defensive replacement for the fifth-place Cardinals, Burgess appeared in 12 games with two hits in seven at-bats.

He made the team for good, however, in 1934, although still only 23 years old. Whitehead, who had befriended Paul Dean at Columbus, quickly became pals with Dizzy Dean and often stayed out late with the Diz. When Whitehead would express concern about missing manager Frankie Frisch’s curfew, Dizzy Dean would say, “Look, if they ship you out, I’ll go, too.”9

Frisch was enamored with Whitehead’s fielding prowess and made sure he got plenty of playing time. For the year, Whitehead appeared in 100 games, 48 at second base, 29 at shortstop, and 28 at third, with one pinch-hit at-bat. (In a half-dozen games he played more than one position.) Although he played in only one game of the World Series, he was able to put his World Series money to good use, helping his parents save their tobacco farm back in North Carolina.10

Whitehead was unable to crack the Cardinals’ starting infield again in 1935, and spent another season as a semi-regular. In 107 games and 338 official at-bats, he hit .263. He frequently spelled the 36-year-old Frisch, appearing in 80 games at second base. Whitehead was named to the National League All-Star team and appeared as a pinch-runner during the contest in Cleveland.

The way was paved for Whitehead to become a starter after the 1935 regular season, only it would not be for the Cardinals. On December 9 St. Louis shipped him to the New York Giants for starting pitcher Roy Parmelee, as outfielder Phil Weintraub, relief pitcher Allyn Stout, and infielder Al Cuccinello.11 The Giants, who in 1935 had finished in third place, 8⅓ games behind the pennant-winning Cubs, had long been in need of a second baseman, but many thought they had given up too much for Whitehead, who had never played regularly and who many considered too frail to play every day.12 (He is listed at 5-10½ and 160 pounds.) Dizzy Dean, however, knew what the Cardinals had lost, telling a reporter that the Giants had picked up “the best second baseman in the business, or the next best, anyhow, outside of Billy Herman.”13

Whitehead raised some eyebrows when he showed up to the Giants’ spring training with a tennis racket.14 But the trade turned out to be a stroke of genius by Giants manager Bill Terry. With Whitehead’s addition the only significant lineup change, the 1936 Giants won the pennant by five games over the Cubs and Cardinals.15 Burgess played all 154 games, teaming with shortstop Dick Bartell to form a stellar keystone combination. He batted a solid .278 in 632 at-bats and led the team with 14 stolen bases to prove his doubters wrong.

In the first game of the World Series against the powerful Yankees, Whitehead made a memorable play to preserve a 2-1 eighth-inning lead for Carl Hubbell. With runners at first and third, he raced to his left to spear a low line drive off the bat of Joe DiMaggio, then wheeled and threw to Bill Terry at first to double off Red Rolfe.16 Whitehead struggled mightily at bat in the World Series, however, going 1-for-21 as the Giants eventually lost to the across-the-Harlem River Yankees in six games.

On July 11, 1936, the Giants played a memorable game against the Cardinals in Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis. Dizzy Dean was on the mound and was known to groove one occasionally to his pals on other teams. Whether he did or not to Whitehead in the sixth inning is a matter of speculation, but in any event, Whitehead smashed a line drive off Dean’s forehead, knocking him unconscious for about seven minutes.17 The ball bounded into the left-field corner for a double; Whitehead, however, was distraught over the incident.18

Whitehead later denied that Dean ever took it easy on him, saying that those Giants-Cardinals games were too important. In a 1975 interview he said, “I can remember more than once passing Diz on the field at the Polo Grounds after I’d been traded and he would say, ‘Sorry, Whitey, Ol’ Diz is pitching. So be ready to go down.’ And down I’d go.”19

Whitehead had an even better year in 1937 as the Giants won their second consecutive pennant, this time by three games over the Cubs. He again played in every game at second base and increased his batting average to .286. His fielding was spectacular as he led all second basemen in putouts (394), double plays (106), and fielding percentage (.974), while finishing second in assists (514) and total chances per game (6.1). He made the National League All-Star team for the second time, although he again appeared in the game only as a pinch-runner. The Giants lost again to the Yankees in the 1937 World Series, this time in five games. This time around Burgess hit a more respectable .250, with four hits in 16 at-bats.

On May 19 that season, the Giants had another dust-up with Dean and the Cardinals. Dizzy, trailing 3-1, was being subjected to ugly bench-jockeying from the Giants’ dugout and had been called for a balk when he decided to take matters into his own hands. He proceeded to low-bridge every player in the Giants lineup except his buddy Whitehead and his respected opposite, Carl Hubbell.20

Whitehead’s slick fielding led Ethan Allen to nickname him “The Gazelle.”21 He also reputedly had the largest hands in baseball and although soft-spoken and “courteous to a fault,” would “jump for joy when he made a good play.”22 He also had a reputation, at least in the press, as being something of a Renaissance man. One sportswriter wrote that “[he] could probably answer every question you asked on philosophy, psychology, and astronomy and then tie you in knots with a few of his own. If you seated him at a banquet table he probably would not make one mistake if they put seven different forks in front of him.”23 Still, Whitehead, although a brilliant student and obviously exceedingly bright, was apparently a man without airs, as attested by his close friendship with fourth-grade dropout Dizzy Dean.

Although Whitehead seemed to be riding on top of the world after two pennant-winning seasons with the Giants, his world was about to come crashing down. He came down with appendicitis in February 1938 which was so severe that gangrene had set in.24 He was operated on immediately in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, and barely survived. The ordeal scared the daylights out of him and his convalescence at home was slow. When he finally reported to the Giants just before they broke camp in Hot Springs, Arkansas, he was still in a weakened condition and very concerned that he would do something to reopen his incision.25

Whitehead continued to lose weight, was unable to play once the season opened, and was finally admitted to a New York hospital on April 23 with what was described as colitis.26 There an attending physician announced that Whitehead’s concern over his physical condition had induced a nervous breakdown.27 As a result, Whitehead returned home to rest and missed the entire 1938 season.

He recovered enough to play in about 40 semipro games around his home in the late summer and early fall28 and traveled to New York to accompany the Giants for the last six games of the season, although he was not activated.29 He had recovered enough after the season to marry Ruth Lyon of Windsor, North Carolina, on December 26, 1938. The two had met ten years earlier when Burgess was in college at Chapel Hill and Ruth was attending St. Mary’s, a girls school about 25 miles away. Whitehead had left college without graduating to play professional baseball and so the two had planned on attending Duke University so that they both could work on obtaining their degrees.30

Whitehead’s 1939 return to the Giants, who had slipped to third in 1938, was anything but smooth. He had played in 305 consecutive games in 1936 and 1937 and was convinced that manager Bill Terry had overused him, contributing to if not causing his mental and physical breakdown.31 He was late reporting to spring training in Baton Rouge, and after a slow start there, seemed to play himself into shape. He was in the Giants’ Opening Day lineup, a win over the Brooklyn Dodgers.

On June 6 in the Polo Grounds, Whitehead participated in a record-breaking inning as the Giants hit five home runs in the fourth inning against the Cincinnati Reds in a 17-3 Giants win.32 It was one of two home runs Burgess would hit for the season, and one of only 17 that he had for his career.

As the season wore on, Whitehead again began behaving erratically, sometimes saying he was too tired to play and often arriving at the ballpark just before game time. Finally, manager Terry suspended Burgess on August 16 for violation of team rules. Whitehead reacted to the suspension by appearing the next day at Yankee Stadium in his full uniform, seeking permission to work out with the Yankees. Not surprisingly, Yankees manager Joe McCarthy turned him away.33

Terry reinstated Whitehead after five days, but on September 9 he left the team and was suspended for the rest of the season.34 For the season he batted a career-low .239 in 95 games and 335 at-bats. Although he was only 29 years old, his future with the Giants and indeed in baseball was very much in doubt.35 When later asked about Whitehead during this period, Bill Terry said simply, “He was crazy.”36

Although Whitehead had a difficult year in 1939, he did manage to gain a famous admirer. Actress Tallulah Bankhead wrote that in 1939 she “swooned over Burgess Whitehead because he moved like a ballet dancer. He was Phi Beta Kappa, a brilliant fielder but he couldn’t hit his way out of a paper bag.”37

Amazingly, after his trouble-filled 1939 season on and off the field,38 Whitehead came back strong in 1940 and hit .282 in 133 games and 568 at-bats, with only 17 strikeouts. Manager Terry shifted him to third base to begin the season and he ended up playing 74 games at third, 57 games at second, and four games at shortstop. As one writer noted late in the season, “[t]his is indeed a reconstructed Whitehead; there is no suggestion of the flighty, uncertain Whitey of 1939.”39 But even with Whitehead’s resurgence, the Giants limped to a sixth-place finish, eight games under .500.

On July 31 Whitehead was inadvertently involved in one of baseball greatest tragedies. With the Giants trailing the Reds 4-1 in the bottom of the ninth in the Polo Grounds and a runner on with two outs, Whitehead worked an 0-and-2 count to 3-and-2 before lofting a fly ball just into the stands in right field to bring the score to 4-3. Mel Ott then coaxed a walk off the Reds’ Bucky Walters to bring Harry Danning to the plate as the winning run. Danning responded by hitting an 0-and-2 fastball deep into the left-field stands for a home run and a dramatic 5-4 Giants comeback win.

The Reds catcher that day was Willard Hershberger, filling in for Ernie Lombardi, who was out with an injury to his leg. The 30-year-old Hershberger had a lifelong battle with depression and blamed himself for the defeat for not calling the right pitches. Two days later in Boston, he was again the catcher in a 12-inning, 4-3 loss to the Bees, going 0-for-5 and failing to field a ball topped in front of the plate. The following day, August 3, Hershberger did not show up at the ballpark and was found dead in his hotel room, a suicide victim.40

On the heels of his strong comeback in 1940, the Giants welcomed Burgess back for the 1941 season. Manager Terry moved him back to second base, where he played in 104 of his 116 appearances. Whitehead battled injuries and slumped to a .228 average, the lowest of his career, as the Giants could climb only to fifth place, five games under .500 and 25½ games out of first place.

After the season Mel Ott took over as manager and the Giants proceeded to clean house, selling Whitehead to the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League on December 11. As a result, Burgess spent the 1942 season playing second base in Toronto, where hit .259 and stole 26 bases in 148 games for the sixth-place Maple Leafs. He played well enough to attract the attention of the Pittsburgh Pirates, who purchased his contract at the end of the International League season. Although he reported to the Pirates, a hand injury kept him from appearing in any major-league games at the end of the season.

Although the complete circumstances are lost to history, after the season Whitehead and Frank Rickey, a scout who was Branch Rickey’s brother, paid the way for a black man from North Carolina named Octavius to watch the World Series in New York.41

With World War II in full swing, the 32-year-old Whitehead was inducted into the Army Air Corps later that fall and reported to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, on December 7. He rose to become a staff sergeant, serving as a physical-fitness instructor at Daniel Field, Georgia, and then Miami Beach, Florida. In 1945 he was transferred to Buckley Field in Denver and served as player-coach for the Second Air Force Falcons, playing with former major-league pitcher Lee Grissom among others.42 Whitehead was discharged in October 1945, after missing three full seasons of professional baseball.43

At age 35, Whitehead reported to spring training with the Pirates, who were managed by his old Gas House Gang teammate Frankie Frisch. He made the team and it was hoped that he would be a steadying influence on Billy Cox, the team’s youthful shortstop. Whether or not he was is questionable; Whitehead ran afoul of Frisch during spring training and was suspended on March 13 and reinstated over a month later on April 19.44 Once active, Burgess was slowed by injuries and did not hit much, so the younger Frank Gustine received most of the playing time at second base. For the year, Whitehead batted just .220 in 55 games for seventh-place Pittsburgh.

Not surprisingly, the Pirates gave Whitehead his unconditional release in January 1947, effectively ending his big-league career. In his nine major-league seasons, Whitehead had compiled a .266 batting average. One of the best contact hitters of his era, in 3,563 plate appearances he had struck out only 138 times. Even more amazing is that he was caught stealing only one time in 52 career stolen-base attempts.

Whitehead was not out of work long, however, and signed with the Jersey City Giants of the International League. There he helped the team to the pennant in a very tight race with the Montreal Royals. The Giants prevailed by a half-game and finished with a 94-60 record before being swept in four games in the playoffs by the Buffalo Bisons. Whitehead played in 141 of the 154 games and hit .257 in 508 plate appearances, striking out only 23 times. For his efforts, he was named the second baseman on the International League All-Star team.45

Whitehead was back with Jersey City in 1948 but injuries slowed him to only 79 games for a team that slid all the way to seventh place. Still, at 38 years old, he hit a solid .284 in 316 plate appearances with only 16 strikeouts.

Whitehead called it quits after 1948 and returned to his native North Carolina. He went into the feed mill and livestock business with two brothers in Windsor, North Carolina, where he “had some good years and some rugged ones.”46 He had no formal association with baseball although he did enjoy watching Gaylord Perry pitch when he was a high-school phenom at a nearby town and arranged for him to try out with the crack semipro Alpine Cowboys in far west Texas.47

Whitehead retired from the feed mill business in 1974 and afterward helped out as an assistant golf pro at the Cashie Golf and Country Club.48

He was elected into the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame in 1981 and was the last surviving member of the Gas House Gang when he died from a heart attack on November 25, 1993, at the age of 83. He was survived by Ruth, his wife of almost 55 years; a son, Charles Lyon Whitehead; a daughter, Susan Whitehead Harrell, and four grandchildren.

This biography is included in “The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals The World Champion Gas House Gang” (SABR, 2014), edited by Charles F. Faber.

Sources

Alexander, Charles, Breaking the Slump – Baseball and the Depression Era (New York: Columbia University Press, 2002).

Bartell, Dick, with Norman L. Macht, Rowdy Richard – A Firsthand Account of the National League Baseball Wars of the 1930s and the Men Who Fought Them (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1987).

Barthel, Thomas. The Fierce Fun of Ducky Medwick (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2003).

Barthel, Thomas. Pepper Martin – A Baseball Biography (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2003).

Blaisdell, Lowell L. Carl Hubbell – A Biography of the Screwball King (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2011).

Bloodgood, Clifford, “The Giants Get a Second Baseman,” Baseball Magazine, February 1936.

Broeg, Bob, The Pilot Light and the Gas House Gang (St. Louis: The Bethany Press, 1980).

Daley, Arthur, Times At Bat – A Half-Century of Baseball (New York: Random House, 1950).

Einstein, Charles, ed., The Fireside Book of Baseball (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1956).

Farrington, Dick, “The Man Who Found Himself After Boss Gave Him Up,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1940.

Feldman, Doug, Dizzy and the Gashouse Gang – The 1934 St. Louis Cardinals and Depression-Era Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2000).

Fleming, G.H., The Dizziest Season – The Gashouse Gang Chases the Pennant (New York: William Morrow & Co., Inc., 1984).

Frisch, Frank, as told to J. Roy Stockton, Frank Frisch: The Fordham Flash (New York: Doubleday & Co., 1962).

Golenbock, Peter, The Spirit of St. Louis – A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns (New York: Avon Books, Inc., 2000).

Graham, Frank, The New York Giants (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1952).

Gregory, Robert. Diz – The Story of Dizzy Dean and Baseball During the Great Depression (New York: Viking, 1992).

Grosshandler, Stan, “Burgess Whitehead: Last of the Old Gas House Gang,” Baseball Digest, June 1992.

Heidenry, John, The Gashouse Gang (New York: Public Affairs, 2007).

Hood, Robert E., The Gashouse Gang (New York: William Morrow & Co., Inc., 1976).

Hynd, Noel, The Giants of the Polo Grounds – The Glorious Times of Baseball’s New York Giants (New York: Doubleday, 1988).

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2nd ed., 1997).

Kelley, Brent. The Early All-Stars (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1997).

Lanctot, Neil, Negro League Baseball – the Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: Univ. of Pennsylvania Press, 2004).

Lieb, Frederick G., The St. Louis Cardinals (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1945).

Lowenfish, Lee, Branch Rickey – Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2007).

Martin, Alfred H. Mel Ott – The Gentle Giant (Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2003).

McKelvey, G. Richard, The MacPhails – Baseball’s First Family of the Front Office (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2000).

Neft, David S., Lee Allen, and Robert Markel, eds., The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1969).

Reichler, Joe, and Ben Olan, Baseball’s Unforgettable Games (New York: The Ronald Press Co., 1960).

Smith, Curt, America’s Dizzy Dean (St. Louis: The Bethany Press, 1978).

Stein, Fred, Mel Ott – The Little Giant of Baseball (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1999).

Stein, Fred, Under Coogan’s Bluff – A Fan’s Recollection of the New York Giants Under Terry and Ott (Glenshaw, Pennsylvania, Chapter & Cask, 1981).

Stein, Fred, and Nick Peters, Giants Diary – A Century of Giants Baseball in New York and San Francisco, (Berkeley, California: North Atlantic Books, 1987).

Stockton, J. Roy, The Gashouse Gang and a Couple of Other Guys (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1945).

Tiede, Joe, “Brushbacks, 2 hands, and day (games) gone by,” unidentified Raleigh newspaper, June 1981, in National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead.

Van Blair, Rick, Dugout to Foxhole – Interviews With Baseball Players Whose Careers Were Affected by World War II (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 1994).

Werber, Bill, and C. Paul Rogers, III, Memories of a Ballplayer: Bill Werber and Baseball in the 1930s (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2001).

Williams, Peter, When the Giants Were Giants – Bill Terry and the Golden Age of New York Baseball (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill, 1994).

Clippings file on Burgess Whitehead, National Baseball Library.

Notes

1. Clipping dated February 2, 1936, from the National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead.

2. Clifford Bloodgood, “The Giants Get a Second Baseman,” Baseball Magazine, February 1936.

3. Joe Tiede, “Brushbacks, 2 hands, and day (games) gone by,” unidentified Raleigh newspaper, June 1981, in National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead.

4. Whitehead was originally slated to go to the Rochester Red Wings in the International League but was assigned to Columbus instead.

5. Joe Williams, “Patience of MacPhail Made Whitehead a Keystone Star,” undated column from National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead.

6. Whitehead later said that going 8-for-9 in a doubleheader was his biggest thrill in baseball. Brent Kelley, The Early All-Stars, 177.

7. Columbus then defeated the Minneapolis Millers four games to two in the league playoffs to advance to the Little World Series, where they defeated the Buffalo Bison of the International League five games to three.

8. Columbus was loaded with future major leaguers including Whitehead’s college teammate Lew Riggs, Nick Cullop, Jack Rothrock, Bill DeLancey, and pitchers Bill Lee (21-9), and Paul Dean (22-7).

9. Bob Broeg, “Whitehead a Keystone Gazelle.” August, 30, 1975, unidentified column from National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead.

10. Charles C. Alexander, Breaking the Slump – Baseball in the Depression Era, 198.

11. John Drebinger, “Whitehead Traded to Giants by Cards,” New York Times, December 10, 1935.

12. Dick “Rowdy Richard” Bartell with Norman L. Macht, Rowdy Richard, 162; J. Roy Stockton, The Gashouse Gang and a Couple of Other Guys, 106-07.

13. Peter Williams, When the Giants Were Giants – Bill Terry and the Golden Age of New York Baseball, 189.

14. Fred Stein, Mel Ott – The Little Giant of Baseball, 70-71.

15. Brent Kelley, 177.

16. Noel Hynd, The Giants of the Polo Grounds, 303-04; Joe Reichler and Ben Olan, Baseball’s Unforgettable Games, 347. The Giants scored four more runs in the top of the ninth and went on to win Game One 6-1, breaking the Yankees’ 12-game World Series win streak. In a statistical oddity, the Giants outfielders had no fielding chances for the entire game.

17. Robert Gregory, Diz – The Story of Dizzy Dean and Baseball During the Great Depression, 293; Doug Feldman, Dizzy and the Gashouse Gang, 55; Arthur Daly, Times At Bat – A Half-Century of Baseball, 94; Frank Frisch as told to J. Roy Stockton, Frank Frisch: The Fordham Flash, 100; Thomas Barthel, Pepper Martin – A Baseball Biography, 132.

18. Robert Gregory, 293.

19. Bob Broeg, “Whitehead a Keystone Gazelle.”

20. Dick Bartell, 245-47; Dean’s beanballs apparently drew no warning from the umpires. Not surprisingly, a bench-clearing brawl ensued in the ninth inning after a drag bunt by Jimmy Ripple with Dean covering first. Robert Gregory, 322-24; Noel Hynd, 307-08; Fred Stein, 85-86; Rick Van Blair, Dugout to Foxhole, 67-68.

21. Bob Broeg, “Gas House Gang: Tag Later Than Burgess Whitehead,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 5, 1975, 2C.

22. Robert Gregory, 143-44. His speech was described as a “smooth, syrupy southern voice.” Bob Broeg, “Whitehead a Keystone Gazelle.”

23. Doug Feldman, 55.

24. Clipping dated February 20, 1938, from National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead.

25. Peter Williams, 251.

26. Clipping dated April, 27, 1938, from National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead.

27. Tom Meany, “Chiozza to Carry on at Giant Keystone,” New York World-Telegram, May 3, 1938.

28. Clipping dated December 21, 1938, from National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead.

29. Clippings dated September 16, 1938, and September 27, 1938, from the National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead. Even though he missed the entire year, Whitehead’s teammates voted him a full share of their third-place money. Clipping dated September 27, 1938, from National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead.

30. Dick Farrington, “The Man Who Found Himself After Boss Gave Him Up,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1940. It does not appear that they ever did attend Duke, however.

31. Bob Broeg, “Whitehead a Keystone Gazelle.”

32. The other Giants hitting home runs in the inning were Harry Danning, Frank Demaree, Manny Salvo, and Joe Moore. It was the only home run of pitcher Salvo’s big-league career. The record was later tied by the 1949 Philadelphia Phillies and the 1961 San Francisco Giants. C. Paul Rogers, III, “June 2, 1949, the Day the Phillies Came of Age,” 19, The National Pastime 31 (1999).

33. Clipping dated August 17, 1939, from the National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead. Another account had Whitehead not reporting for the Giants’ game in Ebbets Field against the Dodgers but instead showing up in full uniform in Yankee Stadium. Fred Stein, 101.

34. Fred Stein and Nick Peters, Giants Diary, 84.

35. Harold C. Burr, “Giants to Drop Burgess in ’40,” clipping dated August 17, 1939, from the National Baseball Library clipping file on Burgess Whitehead; Fred Stein, Under Coogan’s Bluff, 74.

36. Peter Williams, 259.

37. Charles Einstein, ed., The Fireside Book of Baseball, 23.

38. According to one unsubstantiated source, Whitehead was involved in both an assault of a woman and a nightclub incident in 1939. Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball – the Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution, 224.

39. Joe King, “Whitehead’s Comeback Is a Success,” unidentified clipping from the National Baseball Library file on Burgess Whitehead dated September 19, 1940.

40. Joe Reichler and Ben Olan, 124-27; Charles C. Alexander, 255-57; Dick Bartell with Norman L. Macht, 293-94; Bill Werber and C. Paul Rogers, III, Memories of a Ballplayer – Bill Werber and Baseball in the 1930s, 175-77.

41. Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey – Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman, 355.

42.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/whitehead_burgess.htm.

43. Brent Kelley, 175; Joe Tiede.

44. Undated clipping from the National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead.

45. Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 357.

46. Brent Kelley, 177.

47. One report has Whitehead helping the Giants sign Perry to a bonus contract (Joe Tiede, “Brushbacks, 2 hands, and day (games) gone by,” unidentified Raleigh newspaper, June 1981, in National Baseball Library clippings file on Burgess Whitehead), but Perry’s recollection is different. According to Perry, based on Whitehead’s recommendation, he and his father flew to Alpine for a tryout in 1957. Perry made the team and was the first high-school player ever to make the Cowboys. Telephone interview with Gaylord Perry, June 7, 2013.

48. Joe Tiede.

Full Name

Burgess Urquhart Whitehead

Born

June 29, 1910 at Tarboro, NC (USA)

Died

November 25, 1993 at Windsor, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.