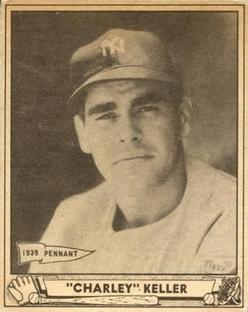

Charlie Keller

At the baseball field in Memorial Park, in Middletown, Maryland, a rural community about fifty miles northwest of Washington, D.C., stands a monument that townspeople erected in honor of Charlie Keller. It’s a bronze plaque affixed atop a waist-high, circular concrete pillar. Beneath a raised profile of Keller is a legend: “Charlie Keller … Middletown’s own … Pride, Character and Sportsmanship.” Below that are listed the highlights of Keller’s career. The pillar stands in the deepest reaches of center field. In 1930, however, the baseball diamond at Memorial Park was reversed, and the spot on which the pillar was erected is the exact place where Charlie Keller stood at home plate and learned to hit a baseball.

At the baseball field in Memorial Park, in Middletown, Maryland, a rural community about fifty miles northwest of Washington, D.C., stands a monument that townspeople erected in honor of Charlie Keller. It’s a bronze plaque affixed atop a waist-high, circular concrete pillar. Beneath a raised profile of Keller is a legend: “Charlie Keller … Middletown’s own … Pride, Character and Sportsmanship.” Below that are listed the highlights of Keller’s career. The pillar stands in the deepest reaches of center field. In 1930, however, the baseball diamond at Memorial Park was reversed, and the spot on which the pillar was erected is the exact place where Charlie Keller stood at home plate and learned to hit a baseball.

Charles Ernest Keller, Jr. was born on September 12, 1916, on a 140-acre farm about 2 1/2 miles east of the park. He was the second child and eldest son of Charles Ernest and Naomi (Kefauver) Keller. In addition to his older sister, Ruth, Charlie had two younger brothers, John (known as Hugh) and Harold, (known as Hal), who became a catcher for the Washington Senators.

All the children worked on the farm. “We all did,” said Jack Remsberg, a cousin of the Kellers who grew up with them, in reference to all the Middletown farm families. Each morning Keller would arise at 4:00 a.m. and help with milking the cows and plowing before heading to school. Such activity developed in the young boy a solid and muscular physique. Remsberg said that after school let out for the day, Charlie would play ball at the field and then run two and a half miles to the farm, where he would change into his work clothes in the barn so his father wouldn’t know he’d been playing.

At Middletown High School, Charlie Keller, Class of 1933, became a schoolboy legend. During the Depression, when he was seventeen, the Kellers lost their farm and moved into town. However bad that was for the family, it gave Charlie the opportunity to develop his athletic skills. In addition to playing baseball, he was a guard on the basketball team, the leading offensive threat on the soccer team, and a runner on the track team. Although primarily a sprinter in the 100-yard dash, Keller once ran a 54-second quarter-mile, which won a state meet.

It was in baseball, however, that he truly excelled. Starting as a catcher, Keller eventually played every position on the diamond, but alternated mostly between pitcher and catcher.1 Keller also played in a weekly Frederick County league, and by the time his senior season arrived he was one of the leading batters in the county. Unfortunately, his senior season was cut short when he was stricken with appendicitis.

That summer, while recuperating, Keller obtained a scholarship to the University of Maryland. Keller was an outstanding student and earned a degree in agricultural economics. Keller worked hard outside the classroom as well. In 2006, his ninety-year old widow, Martha, remembered Keller “dug ditches at the arts and science building,” for which he was paid $15 a month for fifty hours of campus chores. He also became one of the best multisport athletes in the university’s history.2

He played on the freshman baseball and basketball teams (freshmen couldn’t play varsity sports), and by his sophomore year Keller played not only those two varsity sports, but football as well.3 Although he had not played the game in high school, given his build (five feet ten and 190 pounds, with broad shoulders and a thick chest), the athletic department was confident he could take to football as he had to other sports.

Accordingly, when the varsity opened its 1934 season against St. John’s (Maryland) with a 13–0 victory, sophomore Keller made his football debut at left defensive end by “toss[ing] a passer for a 10-yard loss on [Keller’s] first play.” By midseason, though, an ankle injury had sidelined him indefinitely, and, fearing another injury might jeopardize his baseball chances, he decided to drop football.

Clearly, baseball was his future. He had proved to be a slugger from the moment he stepped on campus. In one of his earliest games with the freshman team, practicing against the varsity, Keller “cracked a triple over the center fielder’s head,” and he finished his two varsity seasons with batting averages of .500 and .495; the composite .497 average being at that time the best in school history. His head coach, Burton Shipley, who had managed Hack Wilson at Martinsburg in the Blue Ridge League in 1922, told the press that “Keller looks as good to me as Hack Wilson . . . in 1922.” All Keller needed, opined Shipley, “is a little experience. He has a great arm, he’s fast and he’s a fighter.”4

By the end of his junior season in the spring of 1936, Keller was one of the best college players in the country. Scouts had been coming to College Park for two years to watch him play. In the summer after both seasons, Keller traveled to Kinston, North Carolina, to play in the semiprofessional Coastal Plain League.5 He posted a .385 average in 1935, and a .466 mark with twenty-five home runs in 1936. By the time he returned to College Park, he had accepted an offer from scout Gene McCann to play for the New York Yankees.6

The Yankees had agreed to let Keller finish his education. Once graduated, he was to report in June 1937 to the Newark (Bears, the Yankees’ entry in the International League. As it turned out, he arrived in Newark sooner than expected.

“I read in the papers in March,” Keller said, “that the Newark club had gone to spring training in Sebring, Florida, and I decided that I might just as well start playing ball and get my degree the next year. So I wired [Yankees’ farm director] George Weiss I was on my way.”7

Newark’s manager, Ossie Vitt, was thrilled to have him. Keller was a left-handed hitter, a commodity Newark desperately needed. He arrived in Sebring on March 22 and took batting practice the next day. After watching the twenty-year old slugger, Vitt decided Keller would be his starting right fielder, a position Keller had never played.

The Yankees were hoping Keller would be the left-handed pull-hitter they had been seeking since the departure of Babe Ruth three years earlier, one who would hit home runs into the short porch in Yankee Stadium. Keller, though, wasn’t that type of hitter. Rather than always trying to pull the ball, he usually hit it where it was pitched, hammering doubles and triples lined to left field and center field. Hall of Fame pitcher Herb Pennock, who scouted Keller for the Boston Red Sox, said Keller hit the ball harder to left than any left-handed hitter he had ever seen, except Ruth.8

In his exhibition debut, on March 25, pinch-hitting against the Cincinnati Reds, Keller tripled to left field at Sebring Park. A week later, against the Philadelphia Phillies, he hit a two-run, inside-the-park homer over the center fielder’s head, a hit, exclaimed Philadelphia’s Chuck Klein, playing right field that day, that was “the longest drive [I] ever saw.”9 Still, if the Yankees wanted him to become a pull hitter, Keller, anxious to please, would try to accommodate them.

The experiment lasted for only a year. After trying throughout the 1937 season to please Yankees’ management by pulling the ball, by April 1938 Keller had returned to the style he favored. “They can save Babe Ruth’s crown for someone else,” he said. In 1937 Keller, who won the batting title with a .353 average and led the league in runs and hits, was named both the International League Rookie of the Year and Minor League Player of the Year.

In August 1937 Weiss exclaimed, “What I’m looking forward to is the day when Charlie Keller puts on a Yankee uniform. . . . [he is] absolutely the best outfield prospect in the minor leagues . . . can go and get fly balls with nearly anybody and he has a great arm.”10 Still, Keller was disappointed when he wasn’t invited to New York’s 1938 training camp. “I’d have given any of (the current Yankee outfielders) a real battle,” he said.11 Instead, he grudgingly returned to Newark, where he batted .365 (second in the league) and finished third in league MVP voting.12

Keller had emerged as potentially the next great Yankees’ player. Rival clubs, a newspaper said in May 1938, were “shouting and bidding for Keller’s services all winter and spring.” Bob Quinn, president of the Boston Braves, remarked, “We’d gladly give $75,000 for Keller because he’s a great ballplayer whose punch might even land us a pennant, but it’s no sale. Instead, the Yanks keep him in hock at Newark.”

On January 21, 1938, in Baltimore, Keller wed Martha Lee Williamson, an athletic instructor at a private school. Jack Remsberg remembered Martha, a Baltimore native, as a “beautiful tennis player and golfer.” Keller and Martha had met three years previously when both were students at College Park. Their marriage lasted fifty-two years, until Keller’s death in 1990, and produced three children.

On February 27, 1939, the three-time defending champion Yankees opened spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida. Manager Joe McCarthy had asked Keller to report a week ahead of the regulars so he could personally work with the twenty-two-year-old rookie who had played right field both years at Newark. Keller threw right-handed, explained McCarthy, a trait that “makes him conducive to left field,” and Keller, the manager affirmed, “definitely [is] a left fielder.”13 He was expected to compete with veteran George Selkirk, another left-handed batter, for a starting spot at that position.

McCarthy also wanted Keller to again work on pulling the ball, but Keller was reluctant to do so. He said he didn’t want McCarthy to tinker with his swing. “I can hit well enough to make the grade even with a hitting team like the Yankees,” the rookie said. “I hit with the pitch. I never will be one of those home-run sluggers. If a man cannot bat well, tinker with him. If he can hit, why not let him be?”14 Nevertheless, Keller went to work once again altering his hitting style.

If Keller initially disagreed with McCarthy, over time he came to idolize him. In the book Summer of ’49, David Halberstam wrote that one night on the team train, broadcaster Curt Gowdy, sitting around the bridge table with some of the players, asked of the former Yankee manager, then with the Red Sox, “Wasn’t he a bit of a drinker?” Afterward, Keller followed Gowdy to his train cabin and grabbed him, warning, “I never want you to make another remark about Joe McCarthy like that.” In an interview in 1973, Keller said, the Yankees “were just lucky to have the best manager that ever ran a ballclub.” McCarthy, he said, “was a leader … who had no favorites,” and “insisted that we act like men and it wasn’t long before we were proud that we were acting the way we were.”15

Throughout the spring of 1939, McCarthy mentored Keller. He calmed the rookie and settled him down as he struggled to adapt to the change in batting stroke and often became frustrated. Gradually, Keller’s natural talent took over, and by April 1, when the team broke camp, McCarthy had named him the Yankees’ starting left fielder. But when Opening Day arrived, Keller was not ready to play. A muscle tear he had suffered in his thigh while at Maryland flared up again at Newark, and went without proper treatment. At St. Petersburg the problem returned, and the Yankees’ trainer advised McCarthy that Keller’s debut should be delayed. It wasn’t until April 22 that he played in his first big league game, as a pinch-hitter against the Senators in Washington.

A week passed before Keller played again. He debuted before the home fans on April 29, against Washington. When Joe DiMaggio had to leave the game with an injured foot, McCarthy moved Jake Powell from left field to center field and inserted Keller in left. Keller had four at-bats and collected his first hit, a single off Ken Chase. On May 2, in Detroit, the same day Lou Gehrig ended his legendary consecutive-games streak, Keller made his first start. Playing left field and batting fifth, he hit a triple and a home run and drove in six runs. By June 6, he had started thirty-four games and was batting .319, with twenty-four runs batted in. Still, when DiMaggio returned to the lineup the next day, Keller returned to the bench.

According to Halberstam, when Keller arrived at the ballpark that afternoon and found he was not in the lineup, he cried. McCarthy attempted to console his young player. He told Keller someday he would be a great Yankee star, but he would have to work on pulling the ball more, particularly in Yankee Stadium. For the remainder of that season and, indeed, the rest of his career, Keller heeded McCarthy’s advice.

Throughout most of June and July, Keller was largely forgotten. Then, on August 2, McCarthy put him in right field to replace the slumping Tommy Henrich. From then until the end of the 1946 season (minus 1944 and most of 1945, when he was in the military), Keller not only remained in the lineup, he became one of the most feared sluggers in the American League.

Overall, in 111 games in 1939, he batted .334, fifth in the league, and was fourth with a .447 on-base percentage. In the World Series, as New York swept the Cincinnati Reds, Keller batted a team-high .438, with three home runs and six RBIs.16 After a season of abrupt starts and stops, it appeared that Keller had finally arrived. In 1940, as Henrich re-established himself in right field, Keller returned to left. Together with DiMaggio, the three formed arguably the premier outfield in the game during their time together.

At the University of Maryland, Keller was saddled with the nickname he never cared for, King Kong.17 In 1948, writer Milton Gross visited the team in spring training and reminded readers why Keller had received the appellation. Keller, Gross wrote, “looked massive. His black, beetle-browed eyes, his muscled blacksmith arms, his thick neck and hogshead of a chest were of wrestler’s proportions.”18 As Keller finally matured into the pull hitter the club had always desired, that impressive physique produced equally impressive results.

From 1940 through 1943, playing an average of 143 games a season, Keller batted .287 and had a .531 slugging average. He had 111 home runs, an average of twenty-eight per season, and averaged 102 RBIs over the four years. For all his power, Keller displayed remarkable patience at the plate, averaging 107 bases on balls per year.

On January 20, 1944, Keller, now 27 years old, at the peak of his skills, and earning $15,000 a year, was commissioned an ensign in the United States Maritime Service. For the next twenty months, he served as a purser, sailing the Pacific aboard merchant ships. “I didn’t see or touch a ball the whole time I was away,” he said in a 1973 interview.19 Keller returned in August 1945 to play the final six weeks of the season. “I wasn’t in shape to play,” he admitted.

On January 20, 1944, Keller, now 27 years old, at the peak of his skills, and earning $15,000 a year, was commissioned an ensign in the United States Maritime Service. For the next twenty months, he served as a purser, sailing the Pacific aboard merchant ships. “I didn’t see or touch a ball the whole time I was away,” he said in a 1973 interview.19 Keller returned in August 1945 to play the final six weeks of the season. “I wasn’t in shape to play,” he admitted.

As it turned out, 1946 was the final full season of his career. At the beginning of 1947, the thirty-year-old Keller signed a $22,000 contract. Coming off a season in which he had hit thirty home runs and driven in 101 runs, the Yankees deemed him worth every penny, and he picked up right where he had left off in ’46. On June 5 Keller led the league in home runs, RBIs, and runs scored. That day, though, after walking and collecting a pair of base hits, he complained of soreness in his lower right back, and left in the sixth inning. Afterward, Keller said he had first experienced pain the previous day; he thought it had come from swinging awkwardly. On June 27, with the pain now radiating down his leg, Keller checked into New York Hospital for observation.

He never played another game that season. On July 18 doctors removed a slipped disk from Keller’s spine. The club said he might return in September. Instead, Keller’s career was essentially finished. During the World Series against the Brooklyn Dodgers, he sat in uniform on the bench. A friend suggested that the slugger carry the lineup to home plate before the opening game. “Not for me,” responded Keller. “The next time I go . . . on to that playing field, I’m going out to play, not to try to get some sympathy. I’ll try to be back out there next April. I’ll know if I can make it. If I decide I can’t I won’t go out.”20

For the next two years, the five-time All-Star made a valiant attempt to come back from his injury, but his efforts were largely futile. In 1948 and ’49, although he played in 143 games, only 97 were as a fielder. Ironically, the surgery forced Keller to change his batting style. Instead of “murderously swinging” at each pitch, he favored his back; doing so forced him to cut down on his swing.21 On occasion Keller could still deliver the long ball, but it was soon apparent that his power was gone. Finally, after two seasons of watching him struggle, the Yankees released him on December 6, 1949. “I had some marvelous years and I’ve no regrets,” he graciously remarked.22

And with that, his Yankees playing career came to a close. On September 25, 1948, before 65,507 fans at Yankee Stadium, the team held Charlie Keller Day. With a Maryland delegation on hand, led by Senator Millard Tydings, Keller was presented with golf clubs, a watch and a “pile of other gifts.” With the money he received, the slugger began a University of Maryland scholarship.23

One has only to travel ten miles northeast of Keller’s monument in Middletown to appreciate how he spent the rest of his life. Jack Remsberg said, “Charlie began his life on a farm and ended it that way too.” Before Keller realized his dream, however, he gave baseball one last try.

On December 29, 1949, Keller signed with the Detroit Tigers for $20,000 to be the “the highest-paid pinch-hitter in the game.” Over the next two seasons, in 104 games, he batted .283 and hit five home runs, before Detroit released him on November 9, 1951. The following September, after two evening workouts at Philadelphia’s Shibe Park, Keller sufficiently impressed manager Casey Stengel for New York to re-sign the slugger as a pinch-hitter. After only one at-bat in two games (a strikeout), Keller was released by the Yankees on October 13, 1952. It was a testament to the Yankees’ respect for him that although he’d been with the team only two weeks in 1952, he was awarded a $1,000 World Series share.

Having grown up on a farm, Keller said in 1946, “I’ll know what to do with a good piece of land. Baseball to me means the best farm in my part of the country.” Sixty years later his widow remembered, “That’s why he was playing ball. He wanted a farm someday.” In retirement Keller bought four parcels of land in Frederick, ten miles from where he’d been born, and eventually amassed 300 acres. He lived there the remainder of his life.24

According to Jack Remsberg, Keller initially had standard farm animals, but when milking cows proved too demanding a lifestyle, “he got into the trotting horse business.” In 1955, Yankeeland Farms was born. The former Yankee became a breeder, and over the next thirty-five years Yankeeland Farms became nationally renowned for its line of champion harness racers.

Each day, Keller mucked stalls, repaired fences, and “savored the simplest of farming pleasures.” His son Donald, who worked beside him for thirty years, remembered that his father “liked feeding horses and liked just listening to them eat.” Keller continued to work until he died of colon cancer in 1990 at the age of seventy-three.

Today Charlie Keller rests in the Christ Church Reformed Cemetery in Middletown, two miles from the site of his birth, just behind the high school and a very long home run’s distance to right field from his monument, the place where it all began.

This biography is included in the book “Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees” (University of Nebraska Press, 2013), edited by Lyle Spatz. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Sources

Books

Creamer, Robert W., Stengel: His Life and Times. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984.

Greenberg, Hank, The Story of My Life, edited by Ira Berkow. Chicago: Times Books, 1989.

Halberstam, David, Summer of ’49. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1989.

Kramer, Richard Ben, Joe DiMaggio, The Hero’s Life. New York: Simon and Schuster, 2000.

Ungrady, David, Tales From the Maryland Terrapins: A Collection of the Greatest Stories Ever Told. Sports Publishing, LLC, 2003.

Articles

Frank, Stanley, “Muscles In His Sweat”, Baseball Digest, February 1946.

Gross, Milton, “Charlie Keller’s Comeback”, Sportfolio, September, 1948.

Rumill, Ed, “Hitting the First Pitch”, Baseball Magazine, July, 1948.

Newspapers

Baltimore Sun

Burlington (North Carolina) Daily Times-News

Cumberland (Maryland) Evening Times

Frederick (Maryland) News-Post

Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Mail

Kingsport [Tennessee] Times

Lowell (Massachusetts) Sun

Middletown (Maryland) Times Herald

Monessen (Pennsylvania) Daily Independent

Morning Herald (Hagerstown, MD)

Websites

www.tomdunkel.com/portfolio/article

www.oddsonracing.com/docs/YankeelandFarmClosesMay1506

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_Kinston_baseball_people#Kinston_Professional_Baseball_Hall_of_Fame

http://www.umterps.com/trads/md-wall-of-fame.html

Interviews

Personal interview by author with Jack Remsberg, Charlie Keller’s cousin, at Remsberg’s home on July 2, 2009.

Charlie Keller interview by Kit Crissey, SABR Oral History Committee, February 10, 1973.

Notes

1. When Keller was later at Newark, in May 1938, the press observed that the soon-to-be Yankee superstar was “one of the few young fellows who wanted to be a catcher.” Also, as detailed by author David Halberstam in his book Summer of ’49, when Yankees power pitcher Tommy Byrne, who led the American League in walks for three consecutive years, struggled to harness his wildness, “everyone tried to help with his control problem. Even Charlie Keller,” Halberstam wrote, who was then physically a shell of what he had been, “would put on a catcher’s mitt hoping to help [Byrne] develop a better sense of the target.”

2. Keller was elected to the University of Maryland Athletics Hall of Fame in 1982.

3. About Keller the basketball player, Maryland coach Burton Shipley, who coached him in both basketball and baseball for two varsity seasons, said Keller “played basketball with a gorilla’s abandon” and “would do almost anything to get hold of the ball.” Shipley said Keller “wanted the ball more than anyone I ever coached.” As a junior in 1936, Keller was named All-Southern Conference as a guard, and also served as team captain.

4. Frederick (Maryland) News, March 31, 1935.

5. In 1983, Keller was elected to the initial class of the Kinston Professional Baseball Hall of Fame.

6. Writers have suggested Keller was paid a bonus of $2,500 to $7,500, but in a Frederick Post article from January 12, 1938, Keller claimed McCann gave him ”just a couple of hundred dollars.”

7. Frederick (Maryland) News-Post, June 3, 1939.

8. Frederick (Maryland) News-Post, March 5, 1939.

9. Frederick (Maryland) News-Post, April 19, 1938.

10. Frederick (Maryland) News-Post, August 23, 1937.

11. Frederick (Maryland) News-Post, May 24, 1938.

12. In 1947 Keller was named to the inaugural class of the International League Hall of Fame.

13. Sporting News, March 16, 1939.

14. Sporting News, March 9, 1939.

15. SABR Oral History Commitee interview of Keller by Kit Crissey, February 10, 1973.

16. In four World Series, totaling 19 games, Keller batted a combined .306, with 5 home runs, 18 RBI, a .367 OBP, and a .611 slugging percentage.

17. When Keller left the University of Maryland to sign with the Yankees, the Associated Press described him as “Charlie (King Kong) Keller, ace slugger of the University of Maryland’s baseball team.” (See, for instance, Reading Eagle, March 21, 1937). In Summer of ’49, author David Halberstam related that although Keller was one of the quietest Yankees, he was also “intimidating physically.” When Phil Rizzuto once dared to call Keller King Kong, Keller picked up Rizzuto “with one massive arm” and stuffed the shortstop in an empty locker.

18. Milton Gross, “Charlie Keller’s Comeback,” Sportfolio, September 1948.

19. SABR Oral History Commitee interview of Keller by Kit Crissey, February 10, 1973.

20. Gross, Milton, “Charlie Keller’s Comeback,” Sportfolio, September 1948.

21. In a February 1946 article in Baseball Digest it was written of Keller that “chances are he will never hit .300 consistently; he swings too hard at too many bad pitches.” In a July 1948 issue of Baseball Magazine, Keller was listed with, among others, Jeff Heath and Hal Trosky as “consistent first-ball hitters;” and in his 1973 oral interview, when asked if he preferred to hit a fastball, Keller responded, “I would rather they threw it straight, yeah.”

22. Actually, according to Halberstam, Keller admitted to just one career regret: he “regretted being made a pull-hitter. He and his teammates were sure it had cost him 30 points in average.”

23. In both 1957 and ’59, Keller returned to the Yankees as a coach.

24. Keller’s two sons, Charlie Jr. and Donald, were also ballplayers and Keller managed their Little League teams. Both went on to careers in the Yankees’ Minor League system before back injuries similar to their father’s ended their careers. Charlie played four seasons, and Donald playedn three seasons.

Full Name

Charles Ernest Keller

Born

September 12, 1916 at Middletown, MD (USA)

Died

May 23, 1990 at Frederick, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.