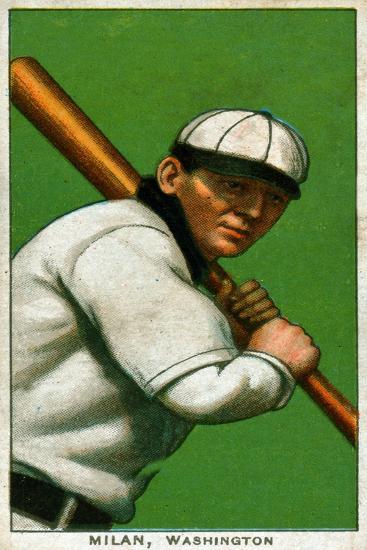

Clyde Milan

He was a left-handed hitter who batted .285 over the course of 16 seasons, and Clark Griffith called him Washington’s greatest centerfielder, claiming that he played the position more shallow than any man in baseball. Yet Clyde “Deerfoot” Milan achieved his greatest fame as a base stealer. After Milan supplanted Ty Cobb as the American League’s stolen-base leader by pilfering 88 bases in 1912 and 75 in 1913, F. C. Lane of Baseball Magazine called him “Milan the Marvel, the Flying Mercury of the diamond, the man who shattered the American League record, and the greatest base runner of the decade.” It was hyperbole, of course; Cobb re-claimed the AL record in 1915 by stealing 96 bases and went on to swipe far more bases over the decade than Milan, but Deerfoot stole a total of 481 during the Deadball Era, ranking third in the AL behind only Cobb (765) and Eddie Collins (564).

He was a left-handed hitter who batted .285 over the course of 16 seasons, and Clark Griffith called him Washington’s greatest centerfielder, claiming that he played the position more shallow than any man in baseball. Yet Clyde “Deerfoot” Milan achieved his greatest fame as a base stealer. After Milan supplanted Ty Cobb as the American League’s stolen-base leader by pilfering 88 bases in 1912 and 75 in 1913, F. C. Lane of Baseball Magazine called him “Milan the Marvel, the Flying Mercury of the diamond, the man who shattered the American League record, and the greatest base runner of the decade.” It was hyperbole, of course; Cobb re-claimed the AL record in 1915 by stealing 96 bases and went on to swipe far more bases over the decade than Milan, but Deerfoot stole a total of 481 during the Deadball Era, ranking third in the AL behind only Cobb (765) and Eddie Collins (564).

The son of a blacksmith, Jesse Clyde Milan (pronounced “millin”) was born on March 25, 1887, in Linden, Tennessee, a quiet hamlet of about 700 residents nestled in the hills above the Buffalo River, 65 miles southwest of Nashville. He was one of eight children (four boys and four girls), and his younger brother Horace also took up professional baseball, briefly joining him in the Washington outfield in 1915 and 1917. Another younger brother, Frank, became a noted Broadway actor, co-starring alongside Humphrey Bogart in the famed original staging of The Petrified Forest. Baseball was almost unknown in rural Middle Tennessee where the Milans grew up, and Clyde told Lane that he didn’t play much of the sport as a youngster. “To show what little experience I really had, I will say that in 1903 I played in just nine games of baseball, and the following season I didn’t play the game at all,” he recalled. Clyde’s chief sporting interest in those years was hunting for quail and wild turkey with his two setters, Dan and Joe.

In 1905 Clyde traveled several days to join a semipro team in Blossom, Texas, after reading an advertisement that the manager of the club was looking for players. There was a great rivalry that year between Blossom and the neighboring town of Clarksville. “Dode Criss, now with St. Louis, was the star pitcher and batter of the Clarksville team, and he surely was some hitter,” Milan told a reporter in 1910. “Well, we played Clarksville and I not only hit Criss hard, but in the ninth inning, with the bases full, I guess I made the most remarkable catch off of his bat that I have ever made in my life. I don’t know today how I ever got near the ball, but I nailed it and was a hero in Blossom thereafter.” Milan ended up joining Blossom’s rivals, but he wasn’t with the Clarksville team very long before the North Texas League disbanded in mid-July due to an epidemic of yellow fever. Milan then finished up the season in the Missouri Valley League, with the South McAlester Miners in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma).

During his short stint in Clarksville, however, Clyde managed to meet his future bride, Margaret Bowers, whom he visited each offseason for the next eight years. The couple ended up marrying after the 1913 season and eventually made their home in Clarksville where they raised two daughters.

Milan began the 1906 season by hitting .356 for Shawnee (Indian Territory) of the South Central League, but the team again disbanded before Milan received his pay. Disgusted with professional baseball, he was thinking about quitting when he received an invitation to join Wichita of the Western Association. “I felt none too sure that I could make good there, for the company was much faster,” Clyde recalled. That partial season in Wichita saw him hit just .211, but he returned in 1907 and batted .304 with 38 stolen bases in 114 games, attracting the attention of Washington manager Joe Cantillon, who had seen him in a spring exhibition. That summer Cantillon dispatched injured catcher Cliff Blankenship to Wichita with orders to purchase Milan’s contract, then go to Weiser, Idaho, to scout and possibly sign Walter Johnson. In later years Clyde loved to relate Blankenship’s remarks during his contract signing: “He told me that he was going out to Idaho to look over some young phenom. ‘It looks like a wild goose chase and probably a waste of train fare to look over that young punk,’ Blankenship said.” Milan cost the Nats $1,000, while Johnson was secured for a $100 bonus plus train fare.

Milan and Johnson had a lot in common: They were the same age, they both hailed from rural areas–Washington outfielder Bob Ganley started calling Milan “Zeb,” a common nickname for players from small towns–and they were both quiet, reserved, and humble. Naturally, they became hunting companions and inseparable friends, and eventually they became the two best players on the Senators team. “Take Milan and his roommate, Walter Johnson, away from Washington, and the town would about shut up shop, as far as base ball is concerned,” wrote a reporter in 1911.

But stardom was not immediate for Milan. After making his debut with the Senators on August 19, 1907, he played regularly in center field for the rest of the season and batted a respectable .279 in 48 games. In 1908, however, Milan batted just .239, and the following year he slumped to .200, with just 10 stolen bases in 130 games. Cantillon wanted to send him to the minors and purchase an outfielder who could hit, but the Senators were making so little money that they couldn’t afford a replacement. Fortunately for Washington, Jimmy McAleer took over as manager in 1910 and immediately recognized the young center fielder’s potential. Under McAleer’s tutelage, Milan bounced back to hit .279 with 44 steals, and in 1911 he became a full-fledged star by batting .315 with 58 steals.

Milan’s peak was from 1911 to 1913 when he played in every game but one, batted over .300 each season, and averaged almost 74 stolen bases per season. In 1912 he finished fourth in the Chalmers Award voting, and his American League record-breaking total of 88 steals would have been 91 if Washington’s game against St. Louis on August 9th hadn’t been rained out in the third inning. Running into Milan on a train that summer, Billy Evans, who had umpired Milan’s first game back in 1907, remarked on his wonderful improvement in every department of the game, base running in particular. “When I broke in, I thought all a man with speed had to do was get on in some way and then throw in the speed clutch,” Milan told the umpire. “I watched with disgust while other players much slower than me stole with ease on the same catcher who had thrown me out. It finally got through my cranium that a fellow had to do a lot of things besides run wild to be a good base runner. I used to have a habit of going down on the second pitch, but the catchers soon got wise to it and never failed to waste that second ball, much to my disadvantage. Now I try to fool the catcher by going down any old time. Changing my style of slide has also helped me steal many a base that would have otherwise resulted in an out. I used to go into the bag too straight, making it an easy matter for the fielder to put the ball on me, but I soon realized the value of the hook slide.”

In 1914 Milan suffered a broken jaw and missed six weeks of the season after colliding with right fielder Danny Moeller. He rebounded to play in at least 150 games in each of the next three seasons, 1915 to 1917, and he continued to play regularly through 1921, batting a career-high .322 in 1920. Griffith appointed Milan to manage the Nats in 1922 but the job didn’t agree with him; he suffered from ulcers as the club finished sixth, and he was fired after the season amidst reports that he was “too easy-going.”

That marked the end of his major-league playing career, but he continued to play in the minors in Minneapolis in 1923, while serving as player-manager at New Haven in 1924, and Memphis in 1925 and 1926. After retiring as an active player, Milan coached for Washington in 1928 and 1929 and managed Birmingham from 1930 to 1935 and Chattanooga from 1935 to 1937. He also scouted for Washington in 1937 and served as a coach for the Senators from 1938 through 1952.

On March 3, 1953, Clyde Milan died from a heart attack at a hospital in Orlando, Florida, two hours after collapsing in the locker room at Tinker Field. Three weeks short of his 66th birthday, he had insisted on hitting fungoes to the infielders during both the morning and afternoon workouts, despite the 80-degree heat. He was buried in Clarksville Cemetery in his adopted hometown.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily on Clyde Milans’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York, and Henry Thomas’s book Walter Johnson: Baseball’s Big Train (Phenom, 1995).

Full Name

Jesse Clyde Milan

Born

March 25, 1887 at Linden, TN (USA)

Died

March 3, 1953 at Orlando, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.