Cot Deal

Most people who have become baseball fans since 1990 have never heard of Cot Deal. If they look hard, they will find his major league career summarized in six lines of print in the baseball encyclopedias. If they look harder, they will find something about him as a minor league manager or major league coach in old newspapers or team histories. What has not been written is that Cot Deal spent 50 years in the game and, even in his retirement, he continues to be a baseball man.

Most people who have become baseball fans since 1990 have never heard of Cot Deal. If they look hard, they will find his major league career summarized in six lines of print in the baseball encyclopedias. If they look harder, they will find something about him as a minor league manager or major league coach in old newspapers or team histories. What has not been written is that Cot Deal spent 50 years in the game and, even in his retirement, he continues to be a baseball man.

Over the course of those years, he was a teammate of Ted Williams, Stan Musial, and Red Schoendienst; a minor league manager of Bob Gibson; a pitching coach of Catfish Hunter; and a friend and advisor to many hundreds, including hall of famers, stars, and ordinary folks.

The same graciousness that has been part of Cot for all those years was extended to a visitor recently as Cot reviewed his years in and outside of baseball in his Oklahoma City home.

The Deal connection to Oklahoma goes back over 100 years, to just after the days of the 1889 Oklahoma Land Rush. The third of four children born to Roy and Ruth Deal, Ellis Ferguson Deal arrived on January 23, 1923, in Arapaho, a small town in the western part of the state where Roy Deal taught school. The family eventually settled in Oklahoma City, where Ellis grew up and was called Cot for his cotton-top hair color.

All of the children were athletic. The oldest, Roy, Jr., played a season of minor league baseball before retiring due to arm trouble. The youngest, Clarence, was the Oklahoma University third baseman after he came home from being a prisoner of the Germans in World War II. Cot’s sister and brothers all live in the Oklahoma City area today.

Cot’s baseball skills developed early and, as a 16-year old, he was invited by the Pirates to spend a week in Pittsburgh. The Pirates’ manager, Hall of Famer Pie Traynor, is remembered by Cot as “a wonderfully warm man”. At the end of the week in Pittsburgh, Traynor gave the last glove he played with to the high schooler. Sadly, after returning home, Cot used the glove in a practice session, put it down to take batting practice, and never saw the glove again.

After signing with the Pirates two years before his high school graduation, Cot spent 1940 with Hutchinson, Kansas, of the Western Association, batting .312 while splitting time between the outfield and third base. The following two years saw him climb the organization ladder to Harrisburg in the Inter-State League before World War II called. As a physical training instructor for the Air Corps, Cot remained stateside until his discharge in 1945.

The next season was spent with the International League’s Toronto Maple Leafs, where he became a pitcher and was sold to the Boston Red Sox. Late in 1947 he was called up to the Sox where he lost his only decision. He was 2-for-4 at the plate, with a run scored and an RBI in a pinch-hitting role.

During spring training in 1948, after earning a spot as a starting pitcher, Cot hurt his arm for the first time. It was an injury that would plague him for the rest of his career. Reviewing his remaining ten seasons, he says, “In my own mind, I don’t think I should have ever pitched. I hurt my arm early and never really got over it.” Despite the pain, he would eventually pitch in 45 games with the Red Sox and Cardinals, winning three and losing four, and would win another 108 minor league games.

Cot and his sore arm were traded by the Red Sox in 1949 to the Cardinals’ Columbus team in exchange for infielder Charlie Harrington. For the next ten years, he established himself in the organization as a pitcher, outfielder, and switch-hitting pinch hitter. Former teammate Vern Benson recalls, “Cot Deal was one of the best competitors I have ever had the pleasure of playing with”. Another teammate, Jack Faszholz, remembers that “Cot could probably do anything that was required on the baseball field.”

Cot’s one regret from his playing days is that he did not have the chance to be a regular catcher. During spring training of 1951, he asked to be the catcher for Columbus. He earned the job, but a family emergency called him away for a few days and, upon his return, was told by manager Harry Walker that “we need pitching”. He then returned to the mound to win 10 games in spite of his sore arm. From then until he stopped playing in 1959, his on-field action would be divided between the outfield and the mound.

Those eleven years in the Cardinal organization saw a number of accomplishments as he moved from player to coach to manager. Among them were:

–Starting and completing a twenty-inning game for Columbus against Louisville on September 3, 1949. In addition to winning the game and giving up just one earned run in twenty innings, Cot also went 4-for-8 at bat.

–Hitting his only major league home run off Cincinnati’s Bud Podbielan in 1954.

–Being named player-coach at Rochester under manager Dixie Walker in 1956.

–Being named the first manager of the community-owned Rochester Red Wings in 1957 and reaching the playoffs during his second season.

–Finally getting a chance to be a catcher. He recalls, “My ‘most fun’ day was the day in Miami in 1957 when, as the manager, with three catchers (Gene Green, Dick Teed, and Bill Schantz) all hurt, I caught Bob Blaylock in a game. We beat Satchel Paige, and I drove in the winning run. I’ll never forget it.”

–Being honored with Cot Deal Day in Rochester in 1957 and receiving an Olds 88 station wagon.

Among the players Cot managed in Rochester was Billy Joe Bowman, a college all-American who went on to win 56 minor league games and earn All-Star honors in the Southern Association. Bowman says, “I will always remember Cot as one of the few men who would look you straight in the eye whether he be talking to you or you to him and you always felt he cared about you. You will not find many like that in baseball.” Jack Faszholz remembers that Cot was “a very self-confident and intelligent man, respectful to all his teammates.”

The 1959 season brought excitement and disappointment. The excitement came early on the morning of July 26. The Red Wings were in Havana playing a Saturday night game against their International League rivals, the Havana Sugar Kings. At midnight, a celebration began in honor of the new Cuban government of Fidel Castro. Despite music, fireworks, and gunfire, the game continued and, following an 11th inning argument, Cot was ejected by first base umpire Frank Guzzetta.

Utility infielder Frank Verdi replaced Cot in the third base coaching box, and took over while still wearing his protective batting liner inside his cap. As the twelfth inning began, the tumult increased and gunfire erupted inside the stadium. Suddenly, Havana shortstop Leo Cardenas felt a bullet graze his right shoulder, and coach Verdi was struck by a .45 slug which passed through his cap, deflected off the batting liner through his earlobe and glanced off his shoulder. The umpires immediately suspended the game and the Red Wings left that afternoon for Rochester. Verdi, only slightly injured, stayed with the team and kept his bullet-pierced cap as a souvenir. Had Cot remained in the game, without a batting liner, a very different fate might have resulted. (A fuller account of this event can be found in the author’s article, “Gunfire in the Ballpark”, found on the Baseball Almanac site.)

The disappointment of 1959 came after the next road trip with the Red Wings mired in the second division. In early August, Cot announced his resignation to general manager George Sisler, Jr. and planned to return home for the rest of the summer. Before leaving Rochester, however, he received a call from Cincinnati manager Fred Hutchinson, who asked him to be the Reds’ pitching coach. The result was one of baseball’s more unusual trades, in which Cot went to the Reds and their previous pitching coach, Clyde King, replaced him as the manager in Rochester.

Joining the Reds would mark the beginning of a 20-year journey across America as manager, coach, and front-office executive for a variety of organizations. The itinerary reads as follows:

1959-1960 — Cincinnati as pitching coach.

1961 Indianapolis (American Association) as pennant-winning manager.

1962-1964 — Houston as the first pitching coach of the expansion franchise.

1965 New York Yankees as pitching coach.

1966-1967 — Kansas City Athletics as pitching coach.

1968 — Oklahoma City (Pacific Coast League) as manager.

1969 — Oklahoma City (American Association) as manager.

1970-1971 — Cleveland as pitching coach

1972 — Toledo (International League) as coach.

1973 — Toledo as coach and manager.

1973-1974 — Detroit as pitching coach.

1975-1977 — Out of baseball in private business.

1978 — Columbus (International League) as coach.

1979-1982 — Oklahoma City (Pacific Coast League) as coach and interim manager.

1983-1985 — Houston as outfield coach and defensive coordinator.

1986 — Chicago White Sox as assistant farm director.

1987-1989 — San Francisco as minor league organization hitting and outfield coach.

For every stop along the way, for every hiring and every firing, there is a story.

The year and a half in Cincinnati would begin a close friendship with Fred Hutchinson that ended end too soon with Hutch’s death in 1964 at the age of 45. After the 1960 season, their friendship continued from a distance after Cot was asked by general manager Gabe Paul to manage the Reds’ affiliate in Indianapolis. There he led the team to the pennant, but at the price of missing a World Series with the Reds. Ray Rippelmeyer, a 13-8 veteran starter on with Indianapolis, remembers Cot as “one of the best managers I had the opportunity to play for.”

When Harry Craft was hired as the first manager of the Houston Colt .45’s, he was permitted to choose only one of his coaches. Cot was that choice. Three seasons later, the team changed stadiums, nicknames, uniforms, and managers. Exiting with the manager was his hand-chosen pitching coach.

During his years in Houston, Cot made a profound impression on a promising young pitcher and future manager, Larry Dierker, who recalls: “Like most players in the ’60s, I smoked cigarettes. One day, after a workout in Cocoa, Cot saw me smoking and came over with a concerned look on his face. He told me that if I was going to smoke I should at least wait until my heartbeat slowed down and I wasn’t breathing hard. I knew it was bad for me and quit a few years later. But my memory of Cot was that he cared more about us as a father than as a coach. I didn’t come across many coaches or managers with this admirable quality during my 38 years in the game.”

After the 1964 season ended, Cardinals’ manager Johnny Keane quit the world championship team to join the Yankees. His first staff selection was to make Cot his pitching coach. The 1965 season marked the beginning of a decade-long Yankee drought and, following a sixth-place finish, Cot was fired.

Shortly after the season ended, Cot was hired by Kansas City A’s manager Haywood Sullivan. Before spring training began, Sullivan was hired as Red Sox general manager and his replacement in Kansas City was Alvin Dark. The change proved to be a positive one, as Cot found Dark to be “a very, very smart manager. Of all the managers I ever was with, he was the best ‘checker-player’ as far as making moves”. With the A’s still a few years away from their dominance in Oakland, Dark and his staff were relieved and another move was imminent.

During 1968 and 1969, Cot managed Houston’s Triple-A affiliate in Oklahoma City. Both were losing seasons, and 1969 was particularly difficult as the Vietnam War took thirteen players from the roster. One of the few memorable events was when Cot’s oldest son joined the team as a catcher. Randy Deal, a graduate student at the University of Oklahoma at the time, was given permission by the school to take time off to play professional baseball under his Dad. The 89ers finished fifth and Cot was let go at the end of the season.

In 1970, Alvin Dark called and asked Cot to be his pitching coach in Cleveland. When Dark was let go during the 1971 season, Cot stayed on as Johnny Lipon finished out the season.

Lipon moved on in 1972 to manage the Tigers’ International League affiliate in Toledo, with Cot as his pitching coach. In 1973, Cot replaced Lipon as manager and then moved up to the Tigers as their pitching coach when they fired Billy Martin and Art Fowler. He stayed there in 1974, when they named Ralph Houk manager. Houk fired Cot at the end of that season, telling the press, “I need someone with a more positive attitude.” The 1975 Tigers, with a new pitching coach, finished the season last in their division and with the league’s second highest earned run average.

From 1975 to 1977, Cot worked in the Oklahoma City area in private business. But baseball beckoned and, in 1978, he joined the Columbus Clippers and their manager, Johnny Lipon, as a coach.

From 1979 to 1982 he returned to Oklahoma City as a coach in the Phillies’ organization.

In 1983 he rejoined the Houston Astros as a coach under longtime friend Bob Lillis and, following the 1985 season, he joined Lillis in being terminated despite a 248-238 record for those three seasons.

In 1986, Cot’s only front-office experience took place, as White Sox farm director Alvin Dark hired him as an assistant. At the end of the season, General Manager Ken Harrelson and his staff were let go.

The final stop in this long career came with San Francisco as a minor league coach from 1987 to 1989. Following the 1989 season, after fifty years, Cot called it a day and retired.

While baseball has been accused of recirculating managers and coaches from team to team, not every case bears out the “good old boys” syndrome. The people who employed Cot over the years — Fred Hutchinson, Alvin Dark, Johnny Lipon — found his baseball skills and personal integrity to be valuable assets on their teams. The positive comments by players whom he managed and coached testify to his reputation as a teacher and leader. Ray Rippelmeyer recalls that when he “started on a managing and coaching career of my own, I used a lot of what I had learned from Cot Deal.”

During his conversations, Cot frequently reflects on the number of former teammates and friends who are no longer alive. Many of the people for whom he had the highest regard — Fred Hutchinson, Allie Reynolds, Johnny Lipon, “Hoot” Evers, Harry Craft, Mel McGaha, and Mo Mozzali — are gone now. Others remain, and Cot treasures their correspondences. The annual Christmas cards and letters have been replaced to a large extent by e-mail, as Cot’s computer skills reveal a man much younger than his nearly 80 years.

Retirement has been good to Cot as he has watched his family grow and succeed. He and Katie celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary on September 23, 2002. All three children, Randy, Elyse, and Donnie, are employed in health-related fields and all live within several hours of home.

Billy Joe Bowman, whom Cot managed in Rochester, has fond memories of the Deals: “I enjoyed every moment I spent with Cot and Katie. They are a wonderful pair and so down to earth.” Jack Faszholz adds, “My wife was always impressed with how well-behaved and respectful Cot’s and Katie’s kids were.”

Home for the Deals is a lovely lakeside house in suburban Oklahoma City where they, their dog and their cat entertain frequent visits from the children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Their health has been good despite Cot’s battle with prostate cancer beginning in 1989, shortly after he retired. He has long since passed the five-year mark and is officially known as a cancer survivor. He is vocal in recommending that all men over 50 receive an annual checkup. He and Katie recently celebrated their 65th wedding anniversary. In his words, they were “married at 19, parents at 21 — and grew up with our kids.”

He follows baseball closely. When asked about the differences between baseball in the 1940’s and today, he cites several areas:

–The umpires are more powerful and less accommodating than they once were.

–The game has advanced technologically with specialized pitching machines and videotapes.

–The game has become more weighted toward offense with the designated hitter rule, smaller stadiums with less foul territory, and smaller strike zones.

He does not begrudge current players their salaries although he, as a minor league player and major league coach, never approached the incomes they now enjoy. Each winter he went to Puerto Rico to manage in the Puerto Rican League, adding to his income but forgoing his desire to earn a college degree. But the comfort that he and his family enjoy is largely due to his baseball earnings.

In the world of baseball, the term “organization man” is becoming less known in our current era. The names that were synonymous with loyalty — Eddie Popowski, Johnny Pesky, Frankie Crosetti etc. — are harder to come by. Cot Deal was a loyal baseball man; loyal to the organizations he served, loyal to managers who hired him and trusted him, loyal to the fans who supported him.

In his retirement Cot finds pleasure in recalling the “old days,” the players and games of many years ago. He is equally comfortable talking about the game today, its problems and its attractions. Although his interests and commitments range widely, Cot Deal is, in the best sense of the term, a baseball man.

This article originally appeared on www.baseballalmanac.com.

Note

This biography originally appeared in the book Spahn, Sain, and Teddy Ballgame: Boston’s (almost) Perfect Baseball Summer of 1948, edited by Bill Nowlin and published by Rounder Books in 2008.

Sources

Numerous interviews with Ellis “Cot” Deal, 2002-2007

The Sporting News Baseball Guide, 1941-1960

Total Baseball, Sixth Edition

The Professional Baseball Database, Ver. 6.0

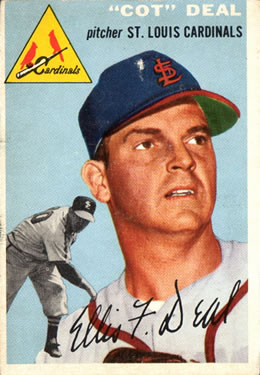

Photo Credit

The Topps Company

Full Name

Ellis Ferguson Deal

Born

January 23, 1923 at Arapaho, OK (USA)

Died

May 21, 2013 at Oklahoma City, OK (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.