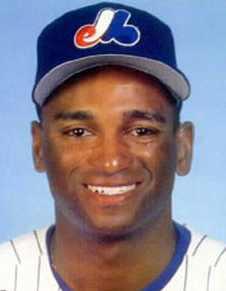

Curtis Pride

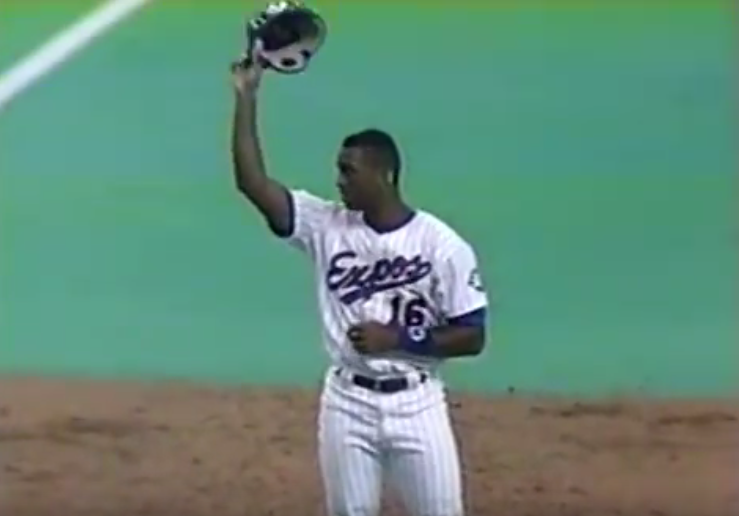

Curtis Pride’s first big-league hit came on September 17, 1993, when he was a member of the Montreal Expos. It was a pinch-hit, two-run double in the seventh inning of a win over the Philadelphia Phillies, whom the Expos were battling for first place in the National League East. As he stood on second base, he could feel the 45,757 strong at Stade Olympique roaring their approval.

Curtis Pride’s first big-league hit came on September 17, 1993, when he was a member of the Montreal Expos. It was a pinch-hit, two-run double in the seventh inning of a win over the Philadelphia Phillies, whom the Expos were battling for first place in the National League East. As he stood on second base, he could feel the 45,757 strong at Stade Olympique roaring their approval.

“The crowd was on their feet giving me a standing ovation that lasted for about five minutes,” remembered Pride. “I felt the cheer. It was so loud, as if the crowd was trying to get me to hear their applause. It was very emotional.”1

Pride was born deaf. He would go on play professionally for 23 years, including parts of 11 seasons at the major-league level. A left-handed-hitting outfielder who stood 6 feet tall and weighed a little over 200 pounds, he primarily served in a reserve role. Of his 199 big-league base hits, 50 came off the bench, including 29 as a pinch-hitter.

Curtis John Pride was born on December 17, 1968, in Washington, DC. His father, John, worked for the US Department of Health and Human Services for 38 years before retiring. His mother, Sallie, was a nurse before becoming a stay-at-home parent once Curtis was found to be deaf.

When Pride was 2 years old, his family moved to Silver Spring, Maryland, where he was enrolled in the Montgomery County Public School System’s Auditory Service infant program. He was then “mainstreamed” into the local school system from seventh grade until his graduation from John F. Kennedy High School in 1986. He was the only hearing-impaired student at the school.

There was no history of deafness in Pride’s family. (Audiologists found him to be 95 percent deaf in both ears as a result of his mother having rubella – German measles – while she was pregnant.) His parents decided to raise him using an oral approach “because of its advantages in the hearing world.” He became a proficient lip-reader and, according to a former teammate, had enough speech that he could be reasonably well understood. It wasn’t until later in life that he learned American Sign Language (ASL).

Language limitations didn’t prevent Pride from becoming an accomplished student and an elite athlete. Aided by good genes – his father played basketball and track in college – Curtis excelled in multiple sports. In 1985 he was named one of the top 15 youth soccer players in the world for his performance in the FIFA U-16 World Championship, in Beijing, China. He would later tell the Guardian that soccer was his best sport, but baseball was his favorite sport to play.

In 1986 Pride received a full basketball scholarship to the College of William and Mary, where he was a starting point guard. Academically, he graduated from high school with a 3.6 GPA before going on to earn a degree in finance, in 1990. Had his dreams of becoming a professional athlete not panned out, Pride was planning to become a financial adviser.

The New York Mets selected Pride in the 10th round of the 1986 draft. That meant decision time. It is rare that a young athlete attends college and plays professional baseball at the same time, but heeding the advice of his father, that’s exactly the road he chose. For the next five years, Pride’s offseasons were spent in the classroom, while his summers were spent honing his skills in the minor leagues.

Pride was just 17 years old when he debuted with the Kingsport Mets of the rookie-level Appalachian League. He appeared in 27 games, logging five hits, one of them a home run, in 46 at-bats. His inexperience showed, as he went down on strikes 24 times.

Pride returned to Kingsport for his age-18 and -19 seasons, putting up better numbers as he matured. Even so, there were developmental obstacles. For one, his academic schedule demanded that he finish his spring semester before resuming baseball activities. That meant no spring training and a late start to the season. Needing to be back at school by the beginning of September, he couldn’t attend the fall instructional league.

From Kingsport, Pride continued his slow climb up the minor-league ladder, spending a year each in Pittsfield, Columbia, St. Lucie, and Birmingham. In 1993, at age 24, he finally broke through. He did so with the Expos, with whom he had signed as a sixth-year minor-league free agent.

Pride began his eighth professional season with Double-A Harrisburg, but he wasn’t there for long. A .356 batting average and 15 home runs in 50 games earned him a promotion to Triple A. Once in Ottawa, Pride hit .302 in 301 plate appearances. His athleticism on display, he swiped 50 bases between the two stops. The Expos called him up in September.

Pride’s pinch-hit double in the extra-inning win over the Phillies was the beginning of something unique. His second big-league hit was a pinch-hit triple. His third was a pinch-hit home run. His fourth was a pinch-hit single. At season’s end, Pride was 4-for-9 and had hit for the cycle. Every one of his at-bats had come as a pinch-hitter.

Pride’s pinch-hit double in the extra-inning win over the Phillies was the beginning of something unique. His second big-league hit was a pinch-hit triple. His third was a pinch-hit home run. His fourth was a pinch-hit single. At season’s end, Pride was 4-for-9 and had hit for the cycle. Every one of his at-bats had come as a pinch-hitter.

The 1994 season was disappointing for both player and team. The Expos had the best record in baseball when the players strike ended any hopes of bringing a championship to Montreal. Meanwhile, Pride spent the entire campaign in Ottawa, hitting a lackluster .257 with 9 home runs.

The 1995 season marked a return to the big leagues, as well as continued reserve-role usage. Pride’s first two hits were of the pinch-hit variety, and the next four came in games he’d entered as a defensive replacement. It wasn’t until his 37th big-league game that he recorded a hit as a member of a starting lineup. He had just 11 hits all year, in 63 at-bats. Half of his season was spent in Ottawa, where his slash line was .279/.339/.448. Come October, he was a free agent for the second time.

Pride, then 26 years old, signed with the Detroit Tigers in March. He went on to have his best season. In 95 games he hit .300/.372/.513, with 10 home runs in 301 plate appearances. He looked ready to establish himself as an everyday player, but it wasn’t to be.

“I was finally given a chance to play on a regular basis, and was able to produce the way I was capable,” explained Pride. “The next year they gave my starting position to a rookie. I let that affect my mental attitude and performance.”

During the offseason, Pride was presented the Tony Conigliaro Award to honor a player who has overcome “an obstacle and adversity through the attributes of spirit, determination, and courage that were trademarks of Conigliaro.”

Thrust back into a supporting role in 1997, Pride hit a lackluster .210 in 79 games, nearly half of which came off the bench. In August the Tigers released him. The Red Sox picked him up, but gave him only two at-bats. The first resulted in a pinch-hit home run, at Fenway Park. The second was a pinch-hit strikeout. At the end of the season, he was cut loose once again.

The roller coaster continued in 1998. Signed by the Atlanta Braves, Pride went on see action in 70 games, but he started just 19 times. He hit a creditable .252/.325/.411, but that wasn’t enough for him keep his job. He was released in December.

Pride reached a crossroads in 1999. The Kansas City Royals inked him to a contract in late February, but released him less than two weeks later. A wrist injury that required surgery was a primary reason, but other factors were at play as well. The journeyman outfielder was now 30 years old, and his track record was admittedly spotty. His allure to big-league organizations was growing dimmer.

Undaunted, he soldiered on. Once his wrist was healed – and with his options limited – he signed with the Nashua Pride of the independent Atlantic League. Rusty from being on the shelf most of the summer, he recorded just a pair of hits in 32 at-bats.

Pride battled his way back to the top, but the roller coaster never stopped. From 2000 to 2008 he played for nine organizations – seven in affiliated ball, and two more in indie ball – and over that time he was either traded or released on 10 separate occasions. Amid the turmoil, there were moments in the sun.

After getting a second cup of coffee in Boston, in 2000 – this time nine games – Pride returned to Montreal the following year for his second go-round with the Expos. He hit a respectable .250 in 76 at-bats. From there it was on to the Pirates’ organization, where he hit .296/.362/.436 for Triple-A Nashville. Continuing an all-too-familiar trend, he was set free at the end of the 2002 season.

With no better offers forthcoming, the resilient 34-year-old returned to Nashua to begin the 2003 season. Sixteen games in, with a .344 batting average on his stat sheet, he was signed by the New York Yankees. Most of his time was spent in Triple A, but he did get into four games with the big-league club. His lone hit, which came in his third at-bat in a Yankees uniform, was a home run.

The following three years were at the same time atypical and emblematic of his career. Pride was in the Anaheim Angels organization from 2004 to 2007, breaking a string of nine consecutive seasons in which he switched allegiances at least once. Signed to a one-year contract each time, he continued to hit well in the minors, but receive a paucity of time in the major leagues. He came to the plate just 86 times in an Angels uniform.

Pride’s last hurrah in professional baseball came close to home. In 2008, at the age of 39, he hooked on with the Atlantic League’s Southern Maryland Blue Crabs. When that 89-game stint came to an end, he’d concluded a 23-year career that saw him play in 421 big-league games, 1,296 minor-league games, and 136 independent-league games.

Pride’s major-league numbers are modest. In 989 plate appearances, he logged 199 base hits and batted.250/.327/.405. His minor-league numbers are far superior, particularly in Triple A. One rung below the majors, he batted.291/.384/.468 over 2,914 plate appearances.

Why Pride didn’t get more opportunities at the highest level – and why he jumped from organization to organization – is somewhat of a mystery. Asked if his deafness played a role, Pride wouldn’t speculate as to whether he was discriminated against. All he’d say was, “Teams appreciated my ability on the field, and more importantly, I was a very good team player.” A former teammate concurred, adding that effort was never a problem – he took pride in every aspect of the game, from hitting to fielding to base-running.

During his career, Pride played for some of the top managers in the majors. Among them were Felipe Alou (Montreal Expos), Bobby Cox (Atlanta Braves), Mike Scioscia (Los Angeles Angels), and Joe Torre (New York Yankees).

Pride didn’t stay away from the sport for long. Shortly after retiring, he accepted the head coaching position at Gallaudet University, the country’s only liberal-arts college for the deaf. In 2014 he led the team to a school record 27 wins. Since taking over the position in 2009, Pride has become fluent in ASL.

Pride resides in Wellington, Florida, with his wife, Lisa (who is hearing), and their two children, both of whom have hearing loss. Noelle, who was 12 years old in November 2016, has bilateral cochlear implants. Colten, 9 years old at the same point 2016, is deaf in his left ear.

Along with his wife, Pride runs the Together with Pride Foundation, whose mission is to “support and create programs for deaf and hard of hearing children that focus on the importance of education and the learning of life skills along with promoting a positive self esteem.”2

In 2010 President Barack Obama announced the appointment of Pride to the President’s Council on Fitness, Sports and Nutrition. The council is a committee of volunteer citizens who advise the president through the secretary of health and human services about opportunities to develop accessible, affordable, and sustainable physical activity, fitness, sports and nutrition programs for all Americans.

In January 2016, Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred announced that Major League Baseball had appointed Pride as an “Ambassador for Inclusion.” In his role, he “provides guidance, assistance and training related to MLB’s efforts to ensure an inclusive environment.” That includes “serv(ing) as a resource for individuals in the baseball family regarding issues related to disabilities.”3

Pride’s story is perhaps best encapsulated in a quote he gave to the New York Times in 1993:

“It’s my life. I was going to do whatever I wanted.”4

Last revised: January 5, 2017

This biography appears in “Overcoming Adversity: The Tony Conigliaro Award” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Clayton Trutor.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com and the following sources:

gallaudetathletics.com/sports/bsb/coaches/pride_curtis?view=bio.

signingsavvy.com/blog/174/Living+Loud%3A+Curtis+Pride+Major+League+Baseball+Player.

Notes

1 All quotations from Curtis Pride come from an email interview with the author in November 2016.

3 m.mlb.com/news/article/161261386/curtis-pride-is-mlbs-ambassador-for-inclusion/.

4 Joe Sexton, “Expos’ Pride Can Feel the Cheers,” New York Times, September 25, 1993. nytimes.com/1993/09/25/sports/baseball-expos-pride-can-feel-the-cheers.html.

Full Name

Curtis John Pride

Born

December 17, 1968 at Washington, DC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.