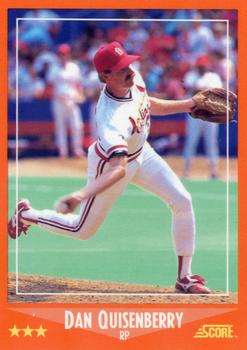

Dan Quisenberry

Lookin Up

Lookin Up

It lasted so long

it went so fast

it seems like yesterday

it seems like never

— “A Career,” from Days Like This, by Dan Quisenberry1

Sigh.

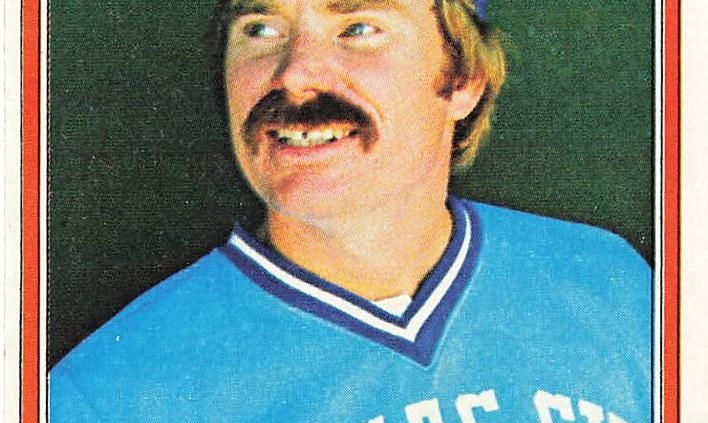

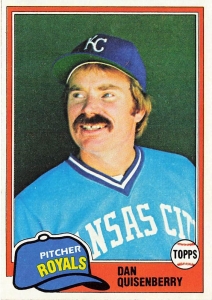

There never was, and maybe there never will be, a major-league pitcher quite like Dan Quisenberry. He literally and figuratively came out of nowhere. Because he was a right-handed submariner, hitters had to turn their heads to pick up his pitches as they materialized out of the third baseman’s jersey and shot across the plate with a cartoonish sink.

Undrafted and signed on a whim by the Kansas City Royals, he became an integral part of their first two World Series teams (1980 and 1985), set the major-league record for saves in a season (45 in ’83) and retired with 244 career saves and a stat line remarkably similar to that of Hall of Famer Bruce Sutter. Perhaps his most amazing number is under the column heading BB/9: In 1,043⅓ innings, he averaged 1.4 walks per nine innings.

He revolutionized relief pitching, yes, but he was so much more than a closer. He was a funnyman, a man of faith, a quote machine, a poet, a loving husband and father, a cherished teammate, a player rep, a humanitarian, a tenacious competitor, and a source of inspiration. He died on September 30, 1998, at the so-unfair age of 45 from a rampaging form of brain cancer. But even then, he had perfect timing: it happened in the bottom of the ninth month.

In his obituary for the Kansas City Star, the estimable Joe Posnanski wrote, “He made everyone who knew him feel alive. … People needed to be near him, needed to feel his arm on their shoulders, needed to tell him a story, needed to hear the wild hunches and beautiful thoughts that clattered around in that amazing mind of his.”2

Even now, decades after his death, his teammates dearly miss him, and some wonder why he’s not enshrined in Cooperstown. With the help of the Royals Alumni Director Dina Blevins, who’s also the daughter of former Royals catcher and manager John Wathan, here’s a small chorus of the men who played beside him.

- John Wathan: “Dan was one of the best people I ever met in baseball. He was a great teammate and friend who didn’t take the accolades he received as individual awards, but as ones that should be shared by all his teammates. Even though he looked more like a professor on the mound than a bulldog, he was a tremendous competitor. I still keep his book of poetry on my night stand by my bed.”

- Pitcher Charlie Leibrandt: “Probably my favorite teammate. We drove to the park every day for several years, and some of the lines he came up with, well, you would swear he spent hours the night before thinking of them, but they were off the cuff. Once, on a road trip to Toronto, we played golf, and Dan took several shots to advance a ball out of the high rough. From that day forward, we started calling him ‘Chopper,’ and it always made us laugh. I still think about him a lot. … A very underrated pitcher, too. He could pitch almost every day and for more than an inning.”

- Catcher Jamie Quirk: “Some of my favorite memories of Quis are about our times in the bullpen. On hot Sunday day games in K.C., he would water down the fans with a hose from the bullpen because he was the ‘fireman.’ He also had a routine of going to the bathroom in the fourth inning, so one night in Boston, where the bathroom is basically an outhouse, we lit a bunch of newspapers on fire and threw them under the door. … He came out with his pants down. For such a humble guy, he had no fear as a pitcher. He trusted his stuff and his infielders. Take Game Three of the 1980 ALCS against the Yankees. He went three and two-thirds to get us to our first World Series. I wish the Royals would retire his number.”

- Outfielder Willie Wilson: “I called him Mr. Wizard. Here’s a memory. He came in with the bases loaded and no outs against the White Sox once. He picks off the man on first, and the batter hits a line drive right at him that he turns into a double play. I can still hear him say, ‘I knew I’d get out of that inning.’ He did things you don’t see relievers do in today’s game, coming in with the bases loaded, pitching multiple innings. His mind was very special, but he had a great heart, too.”

- Infielder Greg Pryor: “He was one of the nicest, most humble players that I ever played with or against. Everybody loved Dan. I just wrote a book, and I titled one of the stories ‘The Day That Dan Quisenberry Yelled at Me.’ Whenever he threw with you, he liked to make a loud. popping sound when the ball hit his glove. We often came into the game together, me for defense, him to close. Well, one night, I’m at third, and I decided to come underneath to him and let one fly at about 85 mph so he could make that familiar ‘Pop!’ sound. It startled him so much that he yelled, ‘Pryor, stop that! You’re throwing harder than I am. … You’re showing me up.’ We both had the biggest laugh on the field.”

- Pitcher Mark Gubicza: “He was one of the funniest people I’ve ever been around. But he was also an amazingly caring person. He was a perfect example for all of us young players who wanted to be as good off the field as on. On the mound, he was a fierce competitor who pitched multiple innings and never asked for a day off. Personally, I think he was a Hall of Famer.”

- Hall of Famer George Brett: “One thing I remember about Dan is that he never took credit for saves, and always took the blame for losses, regardless of what happened. … Here’s another thing. About one month before his passing, I went to have lunch at his house with him, and he knew he was not going to win this battle. I asked him, ‘Why you?’ And he responded, ‘Why not me? I can handle this.’ That speaks volumes about the type of person he was.”

I practiced my whole life

from day dream days

in social studies

to sandlot games

little league games

hardball

tennis ball

whiffle ball

rock ball

When Quisenberry was in his heyday, Royals bullpen coach Jim Schaffer would pick up the phone 100 times a year, listen to the voice at the other end, then hang up and announce, “The Australian.” That’s because his bullpen ace came from down under.3

He actually came from Santa Monica, California. His more common nickname, “Quiz” or “Quis,” was a natural offshoot of the seamstress-challenging name above the 29 on his jersey. But it also spoke to both his inquiring nature and the riddle of his success. He looked up the derivation of his name once and discovered that there was no such fruit as a quisenberry — the name was an English mutation of the German surname Questenberg.

He and his older (by two years) brother, Marty, were very close. Their mother, Reberta, and father, John, had divorced when the kids were 9 and 7, and because Reberta worked as a color consultant for Revlon, the boys ran through a gauntlet of babysitters. Then Mom remarried a man named Art Meola, who put a little discipline into their lives. “He used to make us work around the house all the time,” Dan told Sports Illustrated in a 1983 profile written by yours truly. “We were forever changing white rocks into redwood chips, or the other way around. We got pretty sassy. We needed to be spanked.”4

But the brothers grew to love Art, a North American Rockwell engineer who encouraged them to play baseball and saved them from the ballroom-dancing careers that Reberta had in mind for them. Although Marty and Dan never played on the same organized team together, they played imaginary ballgames together, outside and inside. The indoor game was Strat-O-Matic. “When I got to the majors,” said Dan, “it was like déjà vu. There I was facing Carl Yastrzemski and Rico Carty again after all these years. Why should I be scared, after I had already been chased down the street by Harmon Killebrew?”5

They both played baseball at Costa Mesa High. Marty was actually considered the better athlete, a submarine pitcher long before Dan dropped down. He played at Orange Coast Community College and Southern California College, where he was scouted by Rosey Gilhousen of the Royals. But then Marty threw his arm out and abandoned baseball for the ministry.

Dan followed his brother to Orange Coast, where he was named the team MVP his second year, 1973. The baseball coach at LaVerne College, Ben Hines, recruited him to play there. True to his restless mind, Dan kept switching his majors, from business to religion to sociology to psychology to history. But his most fateful class was square dancing, which was a course Hines encouraged his players to attend because it improved their balance and footwork. It was in that class that Dan met Janie Howard, his future bride and soulmate.

At the time, Dan was considered something of a hothead. In later years, when asked what calmed him down, he replied, “Janie and Christianity.”6 In his two years at LaVerne, Quis went 12-2 and 19-7, pitching an astounding 194 innings his senior year and making the NAIA All-America team. But all that work took the edge off his fastball and lowered his delivery point to side-arm. “The scouts were not exactly flocking around the house,” he recalled.7

Hines gave Gilhousen a call and asked him if might be interested in Marty’s younger brother. The scout said that, yes, there was an opening for a pitcher in Class-A Waterloo, Iowa, but that the kid would have to be at Gilhousen’s house within the hour. So Dan drove 10 minutes to Santa Ana in his battered Gremlin, rang the bell, walked in and signed. “I got $500 a month, and the special-covenants clause was left blank. My bonus was a Royals bat that Rosey had in the house, a Royals pen, and a Royals lapel button. I was really pretty excited, especially about the lapel button.”8

much gets blurred

wins, losses, races

mostly I had my head down

down in the trenches

I missed stuff

sometimes the shrapnel

but sometimes I looked up

On June 22, 1975, Quisenberry had an unusual twin bill. That morning, he was formally baptized at a church in Waterloo. That afternoon, in his first game for Waterloo, he pitched a seven-inning, complete-game 5-3 victory over Wausau in the opener of an actual doubleheader.

Read that again. Quisenberry’s professional debut was a complete game. It was also his last start as a minor- or major-league pitcher. Waterloo manager John Sullivan told him right after the game that he was moving him to the bullpen because he needed a reliever who could throw strikes. Dan thought he was being demoted. “I figured that was his best chance to make it,” said Sullivan. “But I didn’t think he’d ever be in the majors.”9

One of his teammates agreed with that assessment. “I didn’t see him going to the big leagues,” said Willie Wilson, who was then 19.10

But Quis did well enough at Waterloo (2.45 ERA with four saves) to be called up to Double-A Jacksonville for eight innings at the end of the season. The next year, 1976, he divided his time between A and Double A, and while he was effective, nobody seemed to notice. After the season was over, he and Janie were married and ended their honeymoon in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho, where they decided to spend the offseason. They lived in an apartment behind a funeral home. By day Dan would work in a sporting-goods store, and by night he worked for the mortuary. In his own words, “Me and another guy would go around picking up dead bodies and throwing them — I’m sorry — putting them in the back of a hearse.”11

He pitched solely for Jacksonville in ’77, appearing in 33 games to a 1.34 ERA, then spent the winter in Mexico, where he and Janie grew closer together in sickness. Back in Jacksonville for the ’78 season, he saved 15 games and had a 4-2 record with a 2.39 ERA, but got the feeling he was stuck. “I made up mind that if I didn’t get to Triple A that next spring, I was going to quit.”12 He even went to Fresno Pacific College that winter to get his teaching certificate.

Luckily for him and the Royals — and unluckily for some California high school that missed out on a very cool history teacher and baseball coach — Quis was assigned to Triple-A Omaha in the spring of ’79. In the beginning of July, when infielder Jerry Terrell went on the disabled list and the Royals were desperate for another arm, they called up Quisenberry.

Years later, when Royals general manager John Schuerholz was asked to identify Dan’s champion within the organization, he said, “The truth of the matter is that we didn’t have anybody else. Necessity is the mother of invention, and in this case, she was the mother of Dan Quisenberry.”13

I was lookin up when I took the ball

for the first time my rookie year

from Whitey Herzog

my knees shook

like I was getting married

Lamar Johnson drilled a two hopper

that Frank White snared with a bound to his right

that I never saw in minor leagues

On July 8, 1979, Quisenberry made his major-league debut. He came into the game against the White Sox in the top of the seventh to face big Lamar Johnson with a man on and one out, and on the second pitch, Johnson grounded the ball to second baseman Frank White, who started a double play — a scene that would be oft repeated in the next few years.

Quis finished the game, giving up two hits, no walks, and no runs, but the White Sox won anyway, 4-2. Nobody at the time thought they were looking at the future. “I’d never heard of him,” said Brett. “He looked funny, he threw funny, he was funny, and I wanted to know why we didn’t go out and trade for somebody.”14

But he did reasonably well the rest of that season, finishing with five saves, a 3-2 record, and a 3.15 ERA. Not bad for a side-armer with one good pitch, a sinker. In a revealing interview for Inside Sports in 1981, Quis told Mike McKenzie, “I wasn’t supposed to stack up by visual standards. Friends couldn’t wait to face me, no heat at all. But I got them out. Having to prove myself became a way of life.”

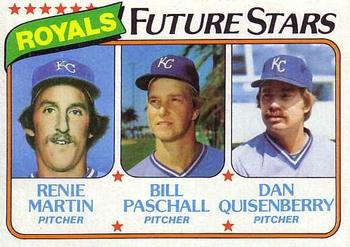

One proof came courtesy of Topps, which put him on a 1980 rookie card alongside fellow pitchers Renie Martin and Bill Paschall.15 Quis would later immortalize the triptych in a poem entitled “Baseball Cards”:

I am the older one

the one on the right

game-face sincere

long red hair unkempt

a symbol of the ’70s

somehow a sign of manhood

you don’t see

how my knees shook on my debut

or my desperation to make it 16

Fate also played a hand early in the spring training of 1980. Jim Frey had replaced manager Whitey Herzog a week after the Pirates beat the Orioles in the ’79 World Series. Well, one of the heroes for Pittsburgh was submariner Kent Tekulve, who had three saves. Frey knew him, and the Royals and Pirates trained not far from each other. So when Quis had a bad outing against the Pirates, Frey went to Tekulve and asked him if wouldn’t mind working with Quisenberry, and Tekulve said sure. Quis, however, was reluctant: “I didn’t think I needed to change.”17

Here’s how he described their first session in Bradenton for Roger Angell in his epic 1985 profile of Quis in The New Yorker: “When the day came, Jim said to Tekulve, ‘We want this guy to be like you. He throws a little like you already, but basically, he doesn’t have shit.’ So (said Quisenberry) it was a total makeover. … Well, I didn’t like this at all. Frey and a lot of our coaches were watching, and I was throwing all over the place and bouncing the ball before it got to the plate. Teke kept saying, ‘Hey, that’s a good pitch, that’s the way to throw,’ and I’m thinking I have no idea what I’m doing. But Jim liked it, and two days later, he put me in another game … and I did real well. I was on my way.”18

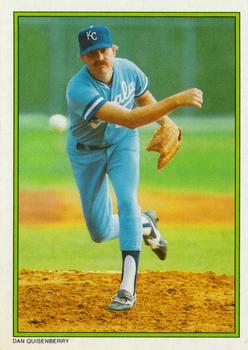

Still throwing his sinker, but now with a motion that resembled a flamingo falling over as it releases the ball, Quisenberry baffled American League hitters in much the same way he baffled the Royals’ front office. His numbers also went against type for relievers: In 128⅓ innings, he struck out only 37 batters while giving up 129 hits, but he also walked only 27. He had 12 wins and 33 saves, and most tellingly, he entered 41 games in which the Royals were leading, and they won all but two of them as they easily won the AL West. And whenever he finished a game with John Wathan catching, Wathan, would say, ‘Way to mix ’em up,’ and Quis would respond, ‘Way to call ’em.’”19

Credit Frey not only for enlisting Tekulve’s help, but also for entrusting so much responsibility to a rookie reliever. The 1980 Royals were a remarkably loose bunch with exemplary leaders like Hal McRae and Brett, who hit .390 that season and came within just five hits of .400. They provided a welcoming environment for Quis — and for a Sports Illustrated writer who was on the baseball beat for the first time. That’s when I first got to know Dan, who was kind of in the same rookie boat as I was, and I couldn’t help but fling away journalistic objectivity. He had a great story to tell, and he told it with a smile on his face.

As a whole, the Royals had as much to prove as he did. Stuck in their craw were the three straight losses to the Yankees in the ’76, ’77, and ’78 playoffs, and they had to face the Bronx Bombers again.

I was lookin up when George Brett hit a Ruthian blast

off a guy who threw as hard as God

Willie Randolph took a called third

why didn’t he swing?

it was right there

and we were series bound

The Royals took the first two games in Kansas City, 7-2 and 3-2, the latter victory coming after Quisenberry got Graig Nettles to hit into a 4-6-3 double play with the tying run on first. Asked what pitch he threw, a deadpan Quis said, “An overhand curve.”20 He hadn’t thrown one in years, of course, but reporters who didn’t know him dutifully took him at his word.

With history and a Yankee Stadium crowd on their side, the Yankees and George Steinbrenner were not expecting to be swept. And for one inning of Game Three, it looked as if they might rally. With the Royals holding a slim 1-0 lead in the bottom of the sixth, Reggie Jackson hit a one-out double off Paul Splittorff, and Frey called for Quis. The wheels promptly fell off when Oscar Gamble singled in the tying run and advanced to third on an uncharacteristic error by Frank White. Quisenberry then gave up the go-ahead run on a single by Rick Cerone before retiring the side.

After Tommy John gave up a two-out double to Willie Wilson in the top of the seventh, Rich Gossage came on. The Yankees had the Royals just where they wanted them. But then U L Washington singled, bringing Brett to the plate. The best closer in the game vs. the best hitter.

Fans will forever remember Brett launching Goose’s first pitch high and far into the third deck in right to give the Royals a 4-2 lead.

What they may not remember, though, is what Quisenberry did to shut the door. After a 1-2-3 seventh, he gave up a leadoff triple to Bob Watson in the eighth, then walked the next two batters to load the bases with no outs. “Sometimes, magical things happen when I let it go,” he used to say, and in that instance, they did — Cerone hit into a line-drive double play (6-4) as Watson held his ground, and Jim Spencer grounded out to second to keep the Yankees off the scoreboard.

With two outs in the bottom of the ninth, Quis struck out Willie Randolph looking at a 3-and-2 pitch.

Alas, the magic ran out in the World Series against the Phillies in a matchup of teams that had never won the fall classic. Frey had come to rely on Quisenberry too much, asking him to pitch in every one of the six games, which in retrospect seems insane since four of his appearances were for multiple innings. As Pete Rose of the Phillies said at the time, “The guy [Frey] is giving us the World Series by letting us look at Quisenberry’s delivery so much.”21

Quis did lose two of the games, but one of the losses came on a two-out single off his glove in the ninth inning of Game Five after he had put out a fire in the seventh and shrugged off a leadoff error in the eighth. As the Phillies celebrated after Game Six, Dan stood at his locker in the visitors’ locker room and graciously offered to take the blame.

He could handle it.

I was lookin up when Janie and I had a girl and a boy

a fifty-day strike, Marvin Miller said

“let’s show em our muscle”

I learned to hang wallpaper

change diapers

grow tomatoes

lose golf balls

After the 1980 World Series, the Royals and the Phillies appeared as opponents on the quiz show Family Feud, and it was small consolation that Kansas City won. Quis also went up against the host, Richard Dawson. Dawson approached him at one point, imitated his underhand delivery and asked, “You throw this way, don’t you? I think it’s effeminate to throw that way.”

After the 1980 World Series, the Royals and the Phillies appeared as opponents on the quiz show Family Feud, and it was small consolation that Kansas City won. Quis also went up against the host, Richard Dawson. Dawson approached him at one point, imitated his underhand delivery and asked, “You throw this way, don’t you? I think it’s effeminate to throw that way.”

Dan laughed, grasped Dawson by the lapels of his sport coat and said, “Is this more comfortable than the popular style?”22

It’s a measure of his wit that when two competing baseball quote books came out in the early ’80s, Quisenberry had seven in each, and only two were repeated.23 And he had only been in the majors for a couple of years. He once explained his humor this way: “There is a correlation between a sinkerball pitcher and being funny. If I try to force my sinker, it doesn’t do a thing. No velocity, no sink. Same with humor.”24

And he was just plain fun, as well as funny. He could keep the denizens of the bullpen amused by conducting a panel to name a hypothetical All-Star team of players they would be most afraid of rooming with. While Renie Martin, his best friend, sang songs about the game in progress, Dan would play Renie’s protuberant teeth as it they were xylophone keys. Once, as he was leading this writer to his house, he pulled up to the gates of a huge mansion in Mission Hills, got out and walked up to them as if he were about to open them. The house actually belonged to Royals owner Ewing Kauffman.

But the 1981 season was not fun, at least not at the start. He came into spring training unhappy about his contract negotiations, and the defending AL champions played dreadfully, costing Jim Frey his job. With a players strike looming, Quis had to juggle his responsibilities as player rep, new father, and closer, and he lost the last of those responsibilities at one point. When the season was interrupted on June 12, the Royals were 20-30. Fortunately for them, the slate was clean when the second half resumed on July 27. After going 10-10, Frey was replaced by Dick Howser on August 31. They won the AL West second half with a 30-23 record and Quisenberry “found a delivery in my flaw” to reclaim his closer role.25 Alas, they were swept by the A’s in the best-of-five Division Series, with Dan getting only one inning of work, a shutout ninth in Game Two.

He again led the league in saves in ’82, with 35, but the Royals, beset by drug problems, finished second in the division. Quis might have once been considered a fluke, but now he was one of the best closers in the game, and it wasn’t just because of his funky delivery. He could get ready in a hurry, so he was often called upon before the eighth or ninth, and he could pitch every day. His fielding skills played into his out pitch, the sinker. And he acquired other pitches for his repertoire: a slider, a changeup, and a knuckleball he found on a tour of Japan. Tigers starting pitcher Milt Wilcox became an admirer: “The smartest thing Dan does is come with a variation of pitches every year. I watch him. He plays the chess game real well. I don’t care what the hitters say, they’re up there guessing.”26

Quisenberry also kept a detailed scouting notebook on each of his outings for future reference. All that hard work paid off in 1983, when he set the major-league record for saves with 45. Take your pick of his incredible stats: 69 games, 139 innings, or better than two an outing! 11 walks, two of them intentional, no hit batsmen, no wild pitches! One HR for roughly every 26 innings! Had WAR been a popular metric back in ’83, Cy Young voters might have made him the second AL reliever to win the award rather than 24-game winner LaMarr Hoyt — Quisenberry’s was 5.5, Hoyt’s was 3.7. Then again, Hoyt’s White Sox did finish 20 games ahead of the second-place Royals.

That summer, shortly before the infamous Pine Tar Game, SI sent me to Kansas City to do a long takeout on Dan. Together, we decided to divide the story into nine innings, and to give him the ninth. His “outing” was mostly humorous, but there was one passage that came from his more serious side:

“I feel a lot of responsibility, more than I used to. If I lost, I used to be able to think it away easier. I could accept the result if I’d thrown a good pitch.”

“It’s not that easy anymore. I feel more guilty if things don’t go right. I think about the starting pitcher and the fans and the owner and the general manager and the friends and relatives who are going to read the paper the next morning, and the guys who built up the lead. Everybody expects me to close up shop nicely, and I feel guilty when I don’t.”

“I don’t want to sound depressing, and I’m only talking about maybe 10% of the games I’m in that I don’t do the job. It’s just that I’ve come to expect a lot more out of myself. So when everything goes right, and I get the save, I’m the one who’s saved.”27

I was lookin up when it was a cool night in October

Darryl Motley caught

A lazy fly off Andy Van Slyke’s bat

Kansas City delirious as champs

we poured champagne on sweat-soaked heads

it burned our eyes

we didn’t care

we screamed we sang we laughed

drunk with victory

He and Janie had always been active in charities, but in May of 1984, they went a step further by establishing the Quisenberry Relief Fund to benefit the Harvesters Food Bank, a Kansas City organization established in 1979 to combat hunger.28 “I feel like we all ought to do our part to better our community or alleviate some problems.”29 Besides making his own generous contribution, he enlisted the help of Warner-Lambert, sponsor of the Rolaids Award he had already won three times.

Quis would win the award again in 1984, with 44 saves and six victories, as the Royals finished first in the AL West, only to get swept by the Tigers in the ALCS. He was the hard-luck loser in Game Two after coming on to start the ninth with the score tied 3-3 — thanks to an error, Detroit broke through for two runs in the 11th.

That ALCS victory helped justify the Cy Young Award and MVP for Tigers reliever Willie Hernandez. But consider this: Quisenberry, who finished second in the Cy Young voting and third on the MVP ballots, saved 12 more games than Hernandez.

The 1985 season began on a high note when co-owner Avron Fogelman signed Quisenberry, Frank White, and Willie Wilson to “lifetime” contracts tied to his real-estate holdings.30

The Royals took years off the lives of their fans, though, by going down to the wire to win the AL West in the regular season, then coming back from 2-0 and 3-1 deficits in the ALCS against Toronto. Quis saved 37 games in the regular season to lead the league for the fourth straight year, but he had blown 12 saves and Howser started losing trust in him, especially after he faltered in Game Two of the ALCS. Still, he did get the final outs in Games Six and Seven.

That set up the I-70, Show-Me State Series against the Cardinals and old friend Whitey Herzog. Once again, the Royals dug themselves a hole, losing the first two games at home. In Game Two, Howser left the southpaw Leibrandt in too long, thinking he had a better chance against the Cardinals’ left-handed hitters than his closer did.31 Dan was not happy about his late arrival.

As it happened, my wife, Bambi, was in St. Louis for Game Three to celebrate our first anniversary, and I was able to secure two seats in the first row of the upper deck in left field, right above the Royals bullpen. In the third inning, we heard our names being called from down below. We looked down, and there were Quis and John Wathan and Jamie Quirk waving to us.32

Even the Cardinals fans around us couldn’t help but be impressed — not by our who-are-you? celebrity, but rather by how loose the team they hoped to sweep seemed to be. Bret Saberhagen pitched a complete-game 6-1 victory, so that was about the extent of the bullpen action that night. Looking up.

John Tudor threw a five-hit shutout as the Cards won Game Four, which turned the Royals’ hopes of winning their first World into prayers — they would need to win three straight elimination games. But Danny Jackson answered with his own five-hitter in a 6-1 victory to send the Series back to Kansas City.

The rest is history … and infamy. The Cardinals had a 1-0 lead in the bottom of the ninth inning in Game Six, and hadn’t coughed up a lead in the ninth all season when Jorge Orta led off the inning with a groundball to first baseman Jack Clark, who tossed the ball to reliever Todd Worrell, racing over to cover first. Umpire Don Denkinger said that Orta had beat the throw, though replays clearly showed that he had not. That opened the door for a rally that ended with former Cardinal Dane Iorg singling home the tying and winning runs. Denkinger was the goat and Iorg the hero in the 2-1 victory, but lost in the hysteria was the lesson learned by Howser, who kept the score close by replacing Leibrandt with Quisenberry at the right time this time.

Game Seven turned into an 11-0 coronation for the Royals, thanks to Saberhagen’s five-hitter and three RBIs by Darryl Motley, who made the final out in right field, unleashing a joyous riot on the field while etching an indelible memory for the Royals faithful cheering in the ballpark and watching at home. President Ronald Reagan made a call to the victorious clubhouse, congratulating, among others, “Jim Quisenberry.”33

Even in victory, there was still an air of disbelief. At the subsequent parade through downtown Kansas City, Quis said from his open convertible, “Sometimes I still think we need to play someone else. It’s hard to believe we don’t have anyone else left to beat.”34

When the Royals visited the Rose Garden of the White House on Halloween, just four days after the final out, President Reagan told them, “You proved to America what a never-say-die spirit can do.”35 He also personally apologized to Quis for calling him Jim.

The pitcher replied, “That’s okay, Don.”36

He almost didn’t make the trip, though. Dan needed to be reassured that the charter flight back to Kansas City would arrive in time for him to trick-or-treat with Alysia, 6, and David, 4. “I would have missed more if I’d missed Halloween than if I didn’t go to the White House,” he said.37

I was lookin up when Dick Howser told us

he couldn’t manage anymore

go on without him

more to life than baseball

he died that summer

we froze and played like statues

The roses faded all too quickly. There was bound to be a letdown after such a tremendous high, but 1986 was a total bummer. The team played with a hangover, and though Quisenberry didn’t pitch that badly, he fell into a closer rotation with Bud Black and Steve Farr. But the real shock came at the All-Star break. Howser, who had been feeling sick and messing up signals, was diagnosed with a brain tumor after leading the AL to a 3-2 victory.38 It was the last game he would ever manage — Mike Ferraro took over the club, which finished with a desultory 76-86 record.

After recovering from brain surgery, Howser tried to come back the next spring training in Fort Myers, but he quickly discovered that he was too weak to do the job. Here’s how Quis described him telling the team he was quitting in “Ode to Dick Howser”:

this small man

who fought big

now looked us in the eyes

just a man

who no longer talked of winning

but hinted at life beyond champagne.39

Billy Gardner was hired to replace Howser, but nobody could. He died on June 17, 1987, at St. Luke’s Hospital at the age of 51. With the team going nowhere at 62-64, Gardner was replaced by John Wathan, who gave it something of a spark. But the Royals still finished second, two games behind the Twins.

The writing was on the wall for Quis as well. Despite a decent ERA of 2.76, he pitched only 49 innings and had only eight saves. He was unhappy about his reduced role, and he made no bones about it. The Royals finally gave him his release on the Fourth of July, 1988 — Independence Day.

I was lookin up when the mirror showed

a red hat on my head

a different logo

it looked foreign

like in a prism

felt it too

like a defector in a new land

except Whitey again was manager

He promptly signed with the Cardinals. The National League appealed to him, and so did reuniting with Whitey Herzog, the first manager to show faith in him. He also drew inspiration from his old mentor, Kent Tekulve. “I watched him fall into disfavor in Pittsburgh and then resurrect himself in Philadelphia,” he told Bob Hertzel of the Pittsburgh Press, “and that has given me a lot of hope.”40

He promptly signed with the Cardinals. The National League appealed to him, and so did reuniting with Whitey Herzog, the first manager to show faith in him. He also drew inspiration from his old mentor, Kent Tekulve. “I watched him fall into disfavor in Pittsburgh and then resurrect himself in Philadelphia,” he told Bob Hertzel of the Pittsburgh Press, “and that has given me a lot of hope.”40

He made 33 appearances for the Cards in ’88, and the results weren’t pretty (a 6.16 ERA). But they brought him back the next year, and he did fairly well, saving six games with a more Quis-like 2.64 ERA. He even got his first — and only — major-league hit, an RBI single off Tim Belcher of the Dodgers, on July 6.

Later that summer, the Cardinals came to New York, and we had lunch. He even came by our apartment, where he threw Wiffle Balls to our baseball-mad 3-year-old son, Bo. Dan knew he was at the end of the line, but he was at peace with his career and looking forward to raising his own two children. The Cardinals released him at the end of the season.

But then, lo and behold, the San Francisco Giants signed him to a modest two-year deal on January 28, 1990.

I was lookin up when I sat at a table with reporters

telling them I quit

telling myself don’t cry don’t cry don’t cry

I didn’t want to break

the unwritten code of big leaguers

When Larry Stone of the San Francisco Examiner asked Quis what he still had to offer, he replied, “I can pitch any time in the game. I don’t get riled. I throw strikes. I can get hitters out. I know how to get along in the clubhouse. I know how to help out the young kids. I throw 100 miles an hour. I hit home runs. I steal bases. You choose the ones that apply.”41

The Giants and Quis were fooling themselves. He pitched in only five regular-season games. For the first time in his career, he had a sore arm. His last appearance came in a 13-3 blowout loss to the San Diego Padres on April 23, 1990. He came on to get one out in the second inning with the Giants already behind 5-0, breezed through the third, then gave up three runs in the fourth.

That was enough. On the day he announced his retirement, the Giants let him take the lineup card out to the umpires. “It’s my turn,” he told the reporters afterward. “A rite of passage. I’m doing what I have to do.” When asked what his plans were, he replied, “I’ve got a big pile of laundry I’ve wanted to get to.”42

It lasted so long

it went so fast

it seems like yesterday

it seems like never

As much as baseball meant to Quisenberry, it wasn’t everything. Retirement gave him the freedom to pour himself into his family and community. The Harvesters Food Bank kept growing, and so did Dan. He took up poetry, eventually amassing enough material to fill a book, On Days Like This. The poems about baseball are under the heading “Covering First,” and the poems about life are under “Stuff That Could Be True.”

Roger Angell, who was the fiction editor at The New Yorker when he wrote about Dan, had this to say about the book: “Like his pitches, Dan Quisenberry’s poems come at you unexpectedly, rising from a different part of the field, clear and unthreatening in their intentions, and then startling you with a late swoop or slant. … [They] turn you back to the top of the page again, wanting more time with this good poet and sweet man.”43

He and the family were on vacation in Colorado in January of 1998 when he noticed his vision had become blurry. He wasn’t expecting the news he got from the doctors back in Kansas City: They found Grade IV malignant astrocytoma in his brain. Soon after surgery to remove the tumor, he and Janie gave a press conference at Royals Stadium. He tried to put everyone at ease. “Every day, I find things to be thankful for,” he said. “My kids take me for rides, so I feel like a dog. I get to stick my head out the window and let the wind flap my ears. I love it.”44

But there was no denying the dire prognosis, and the link to Dick Howser, not to mention the other players from the 1980 postseason who had died of brain cancer: Bobby Murcer, Johnny Oates, Tug McGraw, and John Vukovich. “Dick was such a feisty leader guy,” said Quis. “And then he was this mellow man, saying, ‘Don’t worry about this stuff on the field. Do your best because winning and losing takes care of itself.’ That was so strange to hear. I didn’t really know how to process those words. Now here I am and I know what he was saying. It’s like getting new eyes. So, in a way, it’s a gift. The peace is incredible.”45

On May 30, the Royals inducted Quis into their Hall of Fame.46 He had to be coaxed into attending the festivities before the game with the A’s, but as he and Janie circled Royals Stadium in an antique Corvette convertible, the 30,000 fans and players on both sides showered him with love. “Wow,” he said, “it’s been a long time since I had a good year.”47

Though his vision had diminished, and his shaved head bore the signs of his battle, his mind was as sharp as ever. At an ensuing press conference, a reporter asked him, “Is there a lesson in all this?”

Quis made him define “this,” then begged off answering the question because he didn’t want to come up with a cliché. Later, when another writer asked him about his accomplishments, he said, “I don’t think about those things because I needed so much help. I needed a great wife. I needed Willie Wilson in center. I needed a great second baseman like Frank White.”

Then he turned to the writer whose question he hadn’t answered.

“We need each other. That’s the lesson.”48

Sigh.

Last revised: Februray 21, 2021 (ghw)

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, the Kansas City Royals Alumni Association, and the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library and Research Center.

Notes

1 On Days Like This, by Dan Quisenberry (Kansas City, Missouri: Helicon Nine, Midwest Center for the Arts, 1998). All poems by Dan Quisenberry come from this book.

2 Joe Posnanski, “Quiz, a Royal Remembered,” Kansas City Star, October 1, 1998.

3 Steve Wulf, “Special Delivery From Down Under,” Sports Illustrated, July 11, 1983.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Mike McKenzie, “The Inside Track,” Inside Sports, September 1981.

7 Wulf, “Special Delivery From Down Under.”

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid.

10 Material supplied by Royals Alumni Director Dina Blevins, January 2019.

11 Wulf, “Special Delivery From Down Under.”

12 Ibid.

13 Ibid.

14 Ibid.

15 1980 Topps #667, “Royals Future Stars.”

16 On Days Like This.

17 Roger Angell, “Quis,” The New Yorker, September 30, 1985.

18 Ibid.

19 Wulf, “Special Delivery From Down Under.”

20 Ibid.

21 Roger Launius, “Phillies vs. Royals: Reflecting on the 1980 World Series,” July 20, 2012. https://launiusr.wordpress.com/2012/07/20/phillies-vs-royals-reflecting-on-the-1980-world-series/.

22 Wulf, “Special Delivery From Down Under.”

23 Kevin Nelson, ed., Baseball’s Greatest Quotes (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1982); Bob Chiefger, ed., Voices of Baseball (New York: Atheneum, 1983).

24 Mike McKenzie, “The Inside Track.”

25 Mike McKenzie, “Quisenberry Discovers ‘Delivery in My Flaw,’” The Sporting News, June 6, 1981.

26 Wulf, “Special Delivery From Down Under.”

27 Ibid.

28 Mike Fish, “Quisenberry Launches Campaign to Battle Hunger in the Community,” Kansas City Times, May 24, 1984.

29 Ibid.

30 Associated Press, “Three Royals to Sign Lifetime Pacts,” New York Times, April 3, 1985.

31 Jeffrey Spivak, Crowning the Kansas City Royals (New York: Sports Publishing LLC, 2005), 31.

32 Steve Wulf, “Echoes of the ’85 K.C. Royals,” ESPN.com, October 22, 2014.

33 Ibid.

34 Jeffrey Spivak, 117.

35 Pete Grathoff, “Royals Were Served Cake When They Visited the White House in 1985,” Kansas City Star, July 20, 2016.

36 Wulf, “Echoes of the ’85 K.C. Royals.”

37 Krista Fritz Rogers, “Royal Father,” Kansas City Parent, June 1986.

38 Sarajane Freligh, “Howser Showed Early Signs of Illness,” Chicago Tribune, July 25, 1986.

39 On Days Like This.

40 Bob Hertzel, “Quisenberry Hoping It Works Out for Best With the Cardinals,” Pittsburgh Press, July 27, 1988.

41 Larry Stone, “Quiz Is Still a Quip Wiz,” San Francisco Examiner, March 11, 1990: 35.

42 Rod Beaton, “Quisenberry Says Cheerful Goodbye,” USA Today, April 30, 1990.

43 On Days Like This, back cover.

44 Thomas Boswell, “Quiz Faces the Toughest Test,” Washington Post, January 30, 1998.

45 Ibid.

46 “Pop(ular) Quiz in KC,” USA Today Baseball Weekly, June 3-June 9, 1998.

47 Steve Wulf, “Saving Grace,” ESPN The Magazine, October 3, 1998.

48 Ibid.

Full Name

Daniel Raymond Quisenberry

Born

February 7, 1953 at Santa Monica, CA (USA)

Died

September 30, 1998 at Leawood, KS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.