Greg Pryor

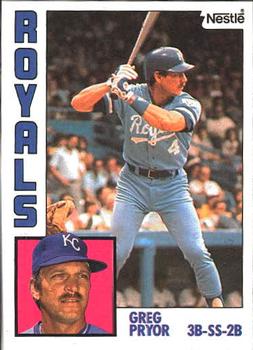

Greg Pryor played professional baseball for 16 years between 1971 and 1987, 10 of them in the major leagues. The 1970s and 1980s were rich and turbulent times for Major League Baseball. Commenting on the game on the field then, Bill James wrote, “Baseball brought into the 1980s a mixture of styles as rich as the game had had in more than a century … There have been few ten-year periods in history that could boast of players succeeding dramatically in so many different ways.”1 1984 saw Pryor’s most dramatic success. Filling for both an oft-injured George Brett and second baseman Frank White, Pryor became a “supersub” as Kansas City won the American League West. The following year, he won a World Series ring with the Royals.

Greg Pryor played professional baseball for 16 years between 1971 and 1987, 10 of them in the major leagues. The 1970s and 1980s were rich and turbulent times for Major League Baseball. Commenting on the game on the field then, Bill James wrote, “Baseball brought into the 1980s a mixture of styles as rich as the game had had in more than a century … There have been few ten-year periods in history that could boast of players succeeding dramatically in so many different ways.”1 1984 saw Pryor’s most dramatic success. Filling for both an oft-injured George Brett and second baseman Frank White, Pryor became a “supersub” as Kansas City won the American League West. The following year, he won a World Series ring with the Royals.

Off the field during these years, the game changed radically. According to Leonard Koppett, “in four short seasons, from 1973 to 1976, the entire structure of baseball would change more than it had in the preceding 90 years.”2 Greg Pryor used the most radical change, free agency, to go from being a Yankee farmhand to a major leaguer with the Chicago White Sox. After the 1984 season, because of free agency, he was able to win a generous contract with the Royals.

He was born Gregory Russell Pryor on October 2, 1949, in Marietta, Ohio, the fourth of six children of George and Martha Pryor. The Pryors came to Ohio from England. During Pryor’s youth, his father was a high school football coach and math teacher at several schools in Ohio. His mother kept house for the growing family.

During Pryor’s youth, his father encouraged his participation in all sports, not just baseball. Pryor speaks of being far more interested in golf and basketball than baseball. He vividly remembers working with his father and his brother Jeff on the problem of how to throw a baseball properly. As Pryor remembers it, “when I started playing little league baseball, my Dad, when he got done at school each day . . . would hurry home and play catch with me and my brother Jeff. To help us learn how to become pitchers, my Dad built two pitcher’s mounds side by side and he also made two home plates out of wood. Jeff and I would throw to him every day off of our own ‘personal’ pitcher’s mounds. Both of us were able to master the ability to throw strikes consistently.”3 This skill enabled both brothers to become star Little League pitchers.

In 1964, when Pryor was a high school sophomore, the family moved to Orlando, Florida. In 1967, Pryor graduated from Maynard Evans High School in Orlando. As a high school baseball player, he was a “decent” second baseman, but at graduation he was only five foot seven inches tall and weighed 150 pounds. He was neither offered a college scholarship nor drafted by a major league team. As Pryor tells it, “When I graduated from high school I got a baseball scholarship to a small college because of my older brother Jeff. Jeff was a great pitcher, and my Dad forced the coach to give me a (small) scholarship by threatening to send my brother to another college.”4

The school with which George Pryor drove the hard bargain was Florida Southern College in Lakeland, Florida. Pryor played part-time second base for the Florida Southern team. For the first two years, he was “the worst hitter on my team.” In part, this was because of a serious injury incurred playing for the Harrisonburg, Virginia, team in a summer collegiate baseball league. Diving for a ball to his left, Pryor suffered “a complete dislocation of my left shoulder.”5 After the injury, his physician told him that he had torn nerves in his shoulder and would never be able to use his left arm again. Pryor would prove the doctor and many others wrong in the course of his career.

The shoulder healed, and Pryor made the NCAA Division II All-America team as a second baseman during both his junior and senior years.6 He had gained five inches and 30 pounds from his freshman season. In June 1971, around the time he graduated with a BS in Industrial Management, Pryor was drafted in the sixth round by the Washington Senators. He reported to Geneva, New York, in the New York-Pennsylvania League. Notably, his future Kansas City Royals teammate, George Brett, was selected in the 1971 draft, as was Mike Schmidt.

As the property of first the Washington Senators (who became the Texas Rangers in 1972) and then the New York Yankees, Pryor spent seven years in the minor leagues, the last three at the Triple-A level. His main position was shortstop, though he played both second and third base too. Versatility would become his trademark as a major-league player.

It wasn’t an easy road. In 1973, the Rangers “optioned him out” to play shortstop for the Rocky Mount Phillies, the Carolina League affiliate of the Philadelphia Phillies. As Pryor remembers it, “I made 49 errors in 126 games. Fortunately, I also hit .293. My manager there was Bob Wellman, my favorite manager over my seasons in the bush leagues. Wellman never expressed discontent with my shaky defensive skills. He never mocked me or criticized me and was a great positive influence on the mental aspects of the game.”7 Pryor was the league’s Player of the Month in July and was named to the Carolina League All-Star team at the end of the season.8

After that season, the farm director of the Rangers, Hal Keller, told Pryor, “You can’t field, you can’t run, you have little power but you can hit a little bit. We don’t know what we are going to do with you.”9 Before the 1976 season, Pryor wrote to the Rangers expressing how upset he was because he wasn’t being offered a raise in salary or invited to the major-league spring training camp. In response, Keller sent him a copy of a report written by a pro scout who saw Pryor play in Spokane, Washington, around the end of July in 1975. The report was brief and dismissive: “All Tools Are Short,” “AAA Player at Best,” “Showed Me Nothing,” “Will Be 27,” “Could Release for Me.”10

Pryor remembers that as a result, he decided to work even harder on his game and to increase his strength between the 1975 and 1976 seasons. It paid off. Although he did not go to the Rangers spring training camp in 1976, he reported to their Triple-A team in Sacramento. Within four months of his receiving that bad scouting report, Pryor was called up to The Show for the first time in June 1976. He spent only 19 days with the Rangers and had three hits in eight at-bats. Over the winter, the Rangers traded him.

In February 1977 he was dealt to the New York Yankees with Brian Doyle for Sandy Alomar, Sr. After he had attended major-league spring training, Pryor was optioned to Syracuse, the Yankees’ farm team in the International League. Aged 28 and broke, Pryor was entering his third straight season in Triple A.

At this point in his baseball career, Pryor was not happy. In a May 1977 article titled “Feuds Brewing Through Entire Yankees’ System” in an unidentified newspaper, Pryor is characterized as “depressed,” feeling that “the Yankees gave him the proverbial shaft during spring training. ‘I’ve been around baseball long enough to know when you haven’t been given a chance and I didn’t get one with the Yankees,’ claimed Pryor. ‘I don’t appreciate what happened to me. I’ve got a bad attitude about the whole thing.’”11

Pryor was so intent on getting away from the Yankees that, in order to get traded or released, he organized a successful Mustache Revolt with his Syracuse teammates. According to Pryor, he told the Yankees that he was growing a mustache — against the organization’s minor-league rules — and that he was not shaving it. Because of this the Yankees were forced to allow all minor-leaguers to begin growing facial hair.12

During a solid season in Syracuse (.271-7-52 in 124 games), Pryor received a call from Marvin Miller of the Major League Baseball Players Association. Miller informed Pryor that he was an “Attachment 11” player and retained free agency rights secured by the 1976 Basic Agreement.13 Being in this category allowed Pryor to choose free agency after the 1977 season, even though the Yankees offered him a two-year contract.

The Yankees had traded for Pryor unaware that they could lose him to free agency at the end of the 1977 season. As Pryor remembers it, during the 1977 season Yankee owner George Steinbrenner summoned him to New York from Syracuse and offered him a two-year guaranteed contract and a call-up to the major league team. Pryor turned the offer down and was called a “dumbass” to his face by Steinbrenner.14 Pryor, though, according to Syracuse newspaper reporter Bud Poliquin, was “content to wait for awhile before signing because he’s hoping to reap what might be a small bonanza in next month’s (Nov. 4) draft.”15 After the season, Pryor was named shortstop on the International League’s All-Star team.

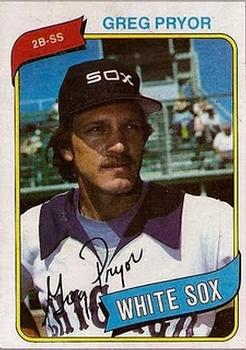

According to Richard Dozer in an October 1978 Chicago Sun-Times article, “Pryor felt he was doomed if he hadn’t joined the 44 minor league players who chose the reentry ‘escape route’ last November. It was an avenue made possible for those who hadn’t signed a contract after August 6, 1976, when the latest basic agreement was implemented.” Dozer quoted Pryor as saying, “I didn’t know anything about it until Marvin Miller told me.” Pryor credits “the Players’ Association chief with opening his eyes. ‘Otherwise I’m staring at 1978 in Triple A.’”16 Instead he worked with his first and only agent, Steve Greenberg, son of Hank Greenberg, to start the season with the Chicago White Sox on a one-year contract with the right to be a free agent after the season. At last, Pryor made the majors for good at the age of 28, thanks to his own persistence and to the gains made by the Players’ Association. Pryor spent his first four years in the majors with the White Sox.

Pryor had spent the winter of 1977-78 playing with the Zulia Eagles in Maricaibo, Venezuela, under Luis Aparicio, longtime major league shortstop and member of baseball’s Hall of Fame.17 As Pryor recalls, “I didn’t get much instruction from Aparicio as he was pretty laid back and just let his players play. I remember him firing his pearl-handled pistol into the ceiling of the clubhouse one time. We all ducked and then he fired it again and started laughing.

“I played [third base] for Zulia from November of ’77 through the end of the Venezuelan League season. Zulia lost to Caracas for the league championship, 4 games to 3. After the championship game in Caracas, the manager of the Caracas team, Felipe Alou, asked me to join his team and travel to the Caribbean World Series in Mazatlan, Mexico. I flew from Caracas and played in the four-team tournament. In my first game in Mexico, I hit a homer off of Mexican League hero, George Brunet. On my third day in Mazatlan, I got extremely sick . . . [and] ended up missing most of the rest of the Caribbean WS games. My experience in playing in the Venezuelan League really made me appreciate living in the United States.”18

At the end of Pryor’s rookie year in the majors, he was honored by the Chicago sportswriters and broadcasters as the co-winner of the Rookie of the Year award for the White Sox, having played in 82 games at three infield positions.19 During 1979 and 1980, he played mostly at shortstop, but by the end of his third season in Chicago he was playing largely in a utility role. His best season was 1979, when he played in 143 games and hit .275.20 That year, Pryor married Michelle Anne Green. They raised three daughters — Paige, Storey, and Hailey.

At the end of Pryor’s rookie year in the majors, he was honored by the Chicago sportswriters and broadcasters as the co-winner of the Rookie of the Year award for the White Sox, having played in 82 games at three infield positions.19 During 1979 and 1980, he played mostly at shortstop, but by the end of his third season in Chicago he was playing largely in a utility role. His best season was 1979, when he played in 143 games and hit .275.20 That year, Pryor married Michelle Anne Green. They raised three daughters — Paige, Storey, and Hailey.

Before the 1980 season, White Sox manager Tony La Russa wanted “to give Pryor the chance to be the kind of super utility player every club needs.”21 Pryor himself had other plans; he wanted a starting job, and he did play 122 games, many at shortstop. But by July he was asked to move to third base, as the club had acquired Todd Cruz to play shortstop.22 In the strike-shortened season of 1981 Pryor played very little. When his trade to the Kansas City Royals was announced in March 1982, he was described as a “utility infielder.”23

Pryor had grown unhappy with his utility role with the White Sox, feeling that he was as good as or better than the players who were playing regularly. Yet with the Royals, who signed Pryor as a “utility player” or “a backup guy,” the situation was different. George Brett, the third baseman, was an All-Star, one of the great players of his generation. Frank White, the second baseman, was an All-Star and consistent Gold Glover. The team was a contender, finishing second in the AL West in 1982 and 1983 and first in 1984 and 1985. In 1985 they were a championship team.

Very soon after he arrived in Kansas City, Pryor’s job was said to be “chief caddy to George Brett,” to step in when Brett was injured and to play the innings of games after Brett’s last at-bat. On July 24, 1983, Pryor was in the left field bullpen at Yankee Stadium during the infamous Pine Tar Incident, in which Brett, having homered to give his team a ninth-inning lead, was called out for having too much pine tar on his bat. Pryor had many opportunities to observe Brett’s use of the sticky stuff. He had this to say: “George Brett was one player who used an abnormal amount of pine tar on his bat around the trademark and right above the trademark. After games, George never wiped any pine tar off of his bats and the clubhouse attendants . . . would not clean his bats after games. Before every game and at-bat. George would apply more pine tar to his bats with the pine tar rag. He would apply fresh pine tar on top of pine tar that was caked on his bats and had long since dried. George always had the most impressive looking bats with pine tar caked on [them]. His bats looked like pieces of antique furniture. He used his bats like they were fine-tuned instruments. “24

1984 was a special year for Pryor. Since Brett and White were both injured at various times during the season, he played 105 games at third base (one more than Brett) and 22 at second. In May 1983, Kansas City manager Dick Howser described Pryor as “excellent,” “steady,” and “a good role player, a guy with some value to a club.”25 After the 1984 season, Tracy Ringolsby (then a Royals beat writer) described him as “an insurance policy, one that paid off big last year.”26 Pryor had graduated from sub to supersub.

In November 1984, Pryor declared free agency, since his contract with the Royals had run out. In September, Ringolsby wrote an article speculating about Pryor’s value to the team. He pointed out that “Pryor’s unexpected playing time has helped him reestablish his value after three seasons of limited activity.” According to Ringolsby, “with free agency on the horizon, Pryor now has to think about his future. He might find a team that will sign him for three or four years and give him a chance to play regularly, or he might sign again with the Royals.” 27

When Pryor opted for free agency, he made it clear that his first choice was to return to Kansas City. He said that “the reason I’m filing is that I went through the whole year knowing I could be a free agent, and I am just following the rules,” which “say I can do this and discuss what interest other teams could have.”28 By the end of the month, he had signed a three-year contract with the Royals supposed to be worth $900,000. In announcing the signing, General Manager John Schuerholz said, “Greg was the epitome of what the team was about … He filled a vital role and sometimes did more than a player in that role is expected to do.”29

The Royals won a World Series championship in 1985, and Pryor was part of it, though he was not needed nearly as often as in 1984. (He also appeared just once in the Series, without an at-bat, as was the case in the 1984 ALCS.)

Pryor played another year for the Royals after the championship year, subbing at third base, shortstop, and second base as needed. Again he played in 63 games, but his batting average declined, reaching a low of .170 in 1986. In September of that year, Schuerholz offered Pryor a job as a coach in the Royals minor-league system, a hint that he might not make the major league roster the next spring.30

Nonetheless, Pryor was not ready then to end his career as a major league player. He came to spring training in 1987 prepared to make the team, though he saw little chance of that happening. Indeed, he was released at the end of March. Bob Nightingale described the scene in the March 29 edition of the Kansas City Star: “Pryor has been a fixture in the Royals’ clubhouse. One by one the Royals’ veterans stopped by his locker and offered their condolences. Even the coaching staff stopped by for a quick visit. George Brett, perhaps Pryor’s closest friend on the team, then pulled out a bottle of champagne from his locker. Written across the label, it said, ‘Thanks for the Memories.’ It was signed by Brett, Buddy Black, Bret Saberhagen, and bullpen coach Jim Schaffer.”31 Nightingale added that Pryor found his release hard to accept.

Pryor’s 16 years as a professional baseball player had in some ways prepared him well for the career in business on which he embarked in 1987 — but in other ways, not so well. In April 1990, some three years after Pryor’s retirement from baseball and his entry into the business world, he was interviewed by Mike DeArmond in the Kansas City Star about the transition. Pryor found the emotional adjustment the most difficult.

“When I finally got a job that started at 8 o’clock (in the morning), it was quite a shock. You know I never saw the sun at this level before. I never saw these people or all these cars. Is this what happens early in the morning?” More seriously, Pryor spoke of the change: “In baseball, you, in essence, work for yourself … It’s you and the ball, totally. You catch it or you don’t. You throw it. You direct the ball. You have that control.” In the business world, “you lose that control, unless you have your own business.” Colleagues in the business world don’t understand this, and the ex-ballplayer has to become reconciled to the fact that he’ll never play again, never get back that control.” Pryor concluded that “I’m never probably going to adjust totally to being out.”32

One way of adjusting was to keep on playing baseball at a lower competitive level. This Pryor did, joining the Men’s Senior Baseball League. A 1999 article in 50 & Better magazine described the successes of his team, the Kansas City Monarchs. By 1999, the Monarchs had won their fourth Senior League World Series title in five years. Previously, Pryor had tried slow-pitch softball and coaching his daughter’s teams without finding what he wanted. He said that Senior League baseball made him “feel young again. Obviously I can’t play as well.”33 Yet it was well enough for his team to become champions again.

In this article, Pryor was identified as the owner of Life Priority Health and Nutrition, Inc. He continued to hold that position in 2017. It was clear that he’d found a perfect post-baseball job. A second 1999 article described Pryor’s being “nine years into the supplement industry and five as the owner of his own company.” Pryor came to that market after finding that supplements helped alleviate his own aches and pains. The level of competition is high, but Pryor the ex-ballplayer is used to and relishes that. “Drug companies and those in the nutritional supplement business lock horns more than they agree. Yet it’s one of the battles that keeps Pryor focused.”34

Pryor concludes that “it was really hard to adjust” in the years after the Royals … “[I] tried various fields, including advertising and insurance, but . . . there wasn’t the passion there that baseball provided then and Life Priority provides now.”35

Last revised: August 25, 2017

Acknowledgements and Sources

This biography would have been impossible without the various contributions of Greg Pryor himself. He provided me with many documents about himself, his ball-playing career, and his post-baseball business. He read and commented on earlier drafts of this biography, and in addition agreed to a telephone interview. These contributions, along with the Greg Pryor file at the Giamatti Research Center at the Baseball Hall of Fame, form the basis of this biography. Pryor’s file at the Giamatti Center was cheerfully and promptly supplied by Cassidy Lent, a reference librarian there.

In addition, I used the following histories for background material on Pryor’s years as a professional ballplayer:

Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (NY: The Free Press, 2001)

Leonard Koppett, Koppett’s Concise History of Major League Baseball (Philadelphia: Temple University Press 1998)

Charles P. Korr, The End of Baseball as We Knew It: The Players’ Union, 1960-1981 (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2002)

Dean A. Sullivan, Final Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball 1972-2008 (Lincoln, Nebraska and London: University of Nebraska Press, 2010).

Pryor’s statistical information came from John Thorn, Pete Palmer and Michael Gershman, eds. Total Baseball (NY: The Viking Press, 1995); Who’s Who in Baseball (NY: 1979-1986); and, especially, Baseball-Reference.com.

This biography was edited by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Notes

1 Bill James,” The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, New York: The Free Press, 2001: 296.

2 Leonard Koppett, Koppett’s Concise History of Major League Baseball, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1998: 353.

3 Upon agreeing to be the subject of a SABR biography, Greg Pryor sent me two documents. The first is a brief biographical sketch. The second, much longer, document runs to 12 pages. Pryor calls it the beginning of “a book on my life in baseball,” and it contains the anecdote above as well as several others cited below.

4 “Biographical sketch,” “My Life in Baseball.”

5 “My Life in Baseball.”

6 Abca.org/awards/all-americans/index.

7 “My Life in Baseball.”

8 Rocky Mount (North Carolina) Evening Telegram, July 27, 1973, 2B; August 26, 1973, 4D.

9 “My Life in Baseball.”

10 Pryor has a copy of this scouting report.

11 “Feuds Brewing Through Entire Yankees System,’ unidentified newspaper clipping, May 7, 1977, Baseball Hall of Fame Library, player file for Greg Pryor.

12 “My Life in Baseball.”

13 “My Life in Baseball.”

14 “My Life in Baseball.”

15 Bud Poliquin, “N.Y. May Ink Pryor,” unidentified Syracuse newspaper, October 17, 1977, player file for Greg Pryor.

16 Richard Dozer, “Chisox Rate Tops in Greg’s Pryor,” Chicago Sun-Times, October 21, 1978, player file for Greg Pryor.

17 Jerome Holtzman, “Chisox Put Their Faith in Numbers,” Chicago Tribune, December 17, 1977, Pryor file.

18 Greg Pryor, email correspondence with Leverett Smith, August 3, 2017. I have rearranged some of Pryor’s sentences.

19 Unidentified newspaper clipping, December 2, 1978, Pryor file.

20 Who’s Who in Baseball, 1982.

21 Bob Marcus, “Chisox Looking for Utility Man But Pryor Has a Different Plan,” January 19, 1981, Pryor file.

22 Joe Goddard, No Defense for Chisox Defense,” June 21, 1980, Pryor file.

23 Unidentified newspaper clipping, March 25, 1982, Pryor file.

24 “My Life in Baseball.”

25 Mike Fish, “There is no Pryor commitment, but Greg has solidified spot on club,” Kansas City Times, May 5, 1984, D5, Pryor file.

26 Tracy Ringolsby, “Just like last year, Pryor ready if needed,” Kansas City Times, March 15, 1985, C1, Pryor file.

27 Ringolsby, “Pryor finds his good fortune with Royals as result of misfortune,” Kansas City Star, Sept. 16, 1984, Pryor file.

28 Patrick Reusse, “Pryor Will Test the Market,” November 5, 1984, Pryor file.

29 Tracy Ringolsby, “Pryor and Royals agree to 3-year deal worth $900, 000,” Pryor file. According to Pryor in an e-mail, the actual amount was $1,005,000.This figure is also mentioned in Bob Nightingale, “Pryor expects to earn his pay this year in KC,” Kansas City Times, March 4, 1987. Tracy Ringolsby, “Just like last season, Pryor ready if needed, Kansas City Times, March 5, 1985, puts the amount at “about $1 million.” (Both articles come from Pryor file.)

30 Bob Nightingale, “Pryor expects to earn his pay this year in KC,” Kansas City Times, March 4m 1987, F3, Pryor file.

31 Nightingale, “Royals say goodbye to veterans Pryor and Law,” Kansas City Star, March 29, 1987, Pryor file.

32 Mike DeArmond, “Pryor is focusing now on succeeding away from baseball,” Kansas City Star , April 29, 1990, Pryor file.

33 Michael Goens, “Super Seniors,” CBN, November 30-December 6, 1999, 8-9.

34 Steve Walker “From the World Series to the World of Health,”50 and Better, 1999.

35 Goens, “Super Seniors.”

Full Name

Gregory Russell Pryor

Born

October 2, 1949 at Marietta, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.