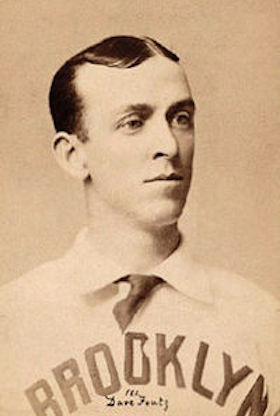

Dave Foutz

Like Bob Caruthers, Jack Stivetts, and Guy Hecker, right-hander Dave Foutz embodied a singular 19th-century baseball species: the staff ace so adept with the bat that he was often penciled into the lineup on his pitching off-days. In fact, after a thumb injury reduced his hurling effectiveness, Foutz spent the latter part of his career as a full-time outfielder-first baseman. By then the practice of using a star pitcher as an off-day position player was vanishing from the major-league scene, and would not survive the coming millennium. Sadly, neither would Dave Foutz. He died prematurely in March 1897 at age 40.

Like Bob Caruthers, Jack Stivetts, and Guy Hecker, right-hander Dave Foutz embodied a singular 19th-century baseball species: the staff ace so adept with the bat that he was often penciled into the lineup on his pitching off-days. In fact, after a thumb injury reduced his hurling effectiveness, Foutz spent the latter part of his career as a full-time outfielder-first baseman. By then the practice of using a star pitcher as an off-day position player was vanishing from the major-league scene, and would not survive the coming millennium. Sadly, neither would Dave Foutz. He died prematurely in March 1897 at age 40.

David Luther Foutz was born on the family farm just north of Baltimore on September 7, 1856. He was the second of 11 children1 born to Abraham Solomon Foutz (1827-1886) and his wife, the former Miriam Cook (1835-1923), both of whose families had resided in Maryland for generations.2 Little is known of Dave’s early life, but by 1878 he was working for the family poultry and produce business. In his leisure time, the long and lanky (6-foot-2, 161 pounds) “Scissors” Foutz played first base for his hometown Waverly, Maryland, amateur club. But he had his heart set on becoming a pitcher and, given a tryout in a pickup match against a crack semipro nine called the Washington Eagles, Dave won both ends of a Fourth of July doubleheader.3

Foutz’s baseball career began in earnest after he followed his older brother, John, to the silver-mining boomtown of Leadville, Colorado, in late 1878. The two prospected with some success, and when time permitted, Dave worked with his brother4 on perfecting the sharp-breaking side-arm curveball that would become his pitching mainstay. Foutz resumed playing ball in 1879, pitching on weekends for the semipro Denver Browns. By 1882 he was playing closer to home and the silver claims staked by the Foutz brothers in and around Leadville. That year he pitched a Leadville club to victory in two high-stakes multigame matches against opposition from Salt Lake City.5 For the season, Dave hurled 40 games for Leadville, winning all but one for a state championship team.6

Dave Foutz entered the professional ranks in 1883, signing with the Bay City (Michigan) club of the newly formed minor Northwestern League. He appeared in the box 43 times for a noncontending (35-49) sixth-place finisher, but his personal pitching log has been lost. In 61 games total, however, he posted a .251 batting average. Despite the club’s poor showing, Foutz quickly became a favorite in Bay City, where his height and unfashionable clean-shaven appearance made him readily recognizable to fans. Although a quiet, affable man who drank little, Foutz was a regular in Bay City saloons, where he used his prowess as a poker player to supplement his ballplayer’s salary.7 The following year, Dave came into his own as a pitcher, posting an 18-4 record before the financially failing Bay City club sold his services to the St. Louis Browns of the American Association.8

On July 29, 1884, Foutz made a successful major-league debut, striking out 13 and yielding only two earned runs in a 13-inning, 6-5 win over Cincinnati. From there, he continued his hot pitching, winning six of eight decisions until felled by malaria, an early manifestation of the susceptibility to illness and injury that would plague Foutz throughout his career. After several weeks on the sidelines, he returned to action, finishing his rookie campaign with an impressive 15-6 record, with a 2.18 ERA in 206? innings pitched. Foutz also played 14 games in the outfield, but batted only .227 with little power, managing only four extra-base hits and no runs batted in over 119 at-bats. The Browns, meanwhile, finished only fourth in AA standings, but a fine 67-40 record and the midseason acquisition of another promising rookie pitcher-outfielder named Bob Caruthers (7-2, and a .268 BA in 23 games), augured better things to come.

The 1885 St. Louis Browns were outstanding, perhaps the best ballclub in the nine-year existence of the American Association. Behind the exceptional pitching of Caruthers (40-13) and Foutz (33-14), and with an everyday lineup that included standouts like field leader/first baseman Charlie Comiskey, third baseman Arlie Latham, outfielders Tip O’Neill and Curt Welch, and catcher Doc Bushong, the Browns went 79-33 (.705) and cruised to the American Association pennant, a full 16 games ahead of the runner-up Cincinnati Reds. The Browns then battled the National League champion Chicago White Stockings to a 3-3-1 draw in a postseason match of league pennant winners, with Foutz posting two of the Browns’ three victories.9

The Browns encored in 1886, breezing to another AA pennant in a campaign that saw Foutz attain his pitching zenith. He led the circuit in wins (41), winning percentage (.719), and ERA (2.11), notwithstanding a lack of overpowering stuff. Instead, Foutz was a finesse pitcher, complementing his sweeping side-arm curve with effective changes of speed and pinpoint control. But it was Foutz’s demeanor that most attracted attention, his cool, unflappable poise serving as a steadying influence on the Browns defense in tight situations. He also helped his club in the field, alternating with Caruthers (30-14, and a .334 BA) in the outfield, batting .280 with 30 extra-base hits and 59 RBIs. With assistance from right-hander Nat Hudson, the star tandem then pitched the Browns to a world championship in a postseason rematch with Chicago.

Another noncompetitive title chase ended with the (95-40) Browns’ third consecutive AA pennant in 1887. The Caruthers-Foutz combo was in customary form until calamity struck in August. Despite introduction of a four-strike requirement and other experimental rule changes designed to bolster offense, Foutz’s record stood at a commendable 23-8 when he entered the box for an August 14 game against the Cleveland Blues. In the first inning, slugger Ed McKean drilled a shot back through the box that struck Foutz squarely on the pitching hand, dislocating his right thumb. Sidelined for five weeks, Foutz was ineffective upon his return, losing four of six late-season outings. He also dropped all three of his decisions in a marathon postseason match lost to the National League champion Detroit Wolverines, 10 games to 5.

It soon became apparent that the thumb injury had permanently impaired Foutz’s ability to snap off his out pitch, the side-arm curve, and his days as a frontline major-league pitcher were now behind him. Happily for Dave, the 1887 season had established his bona fides as an everyday player. Despite being limited to 102 games, he had batted a robust .357, with 43 extra-base hits and 108 RBIs. He had also begun the shift from the outfield back to first base, where his wingspan and athleticism – the long-armed and agile Foutz was an excellent handball player10 – could be put to optimum use.

Like other ballclubs of the era, the St. Louis Browns were not without their share of carousers, prima donnas, and other difficult types. But Foutz was not one of them. Club owner Chris von der Ahe, himself a mercurial hard drinker, later described Dave and catcher Jack Boyle as “quiet [and] gentlemanly, … the best-natured players” Der Poss had ever dealt with.11 Still, Foutz was among the veterans shipped out by von der Ahe in the aftermath of the 1887 championship match disappointment, sold to the Association rival Brooklyn Grays for $5,500 that November.

Joining Foutz in Brooklyn was St. Louis batterymate Doc Bushong, as well as the temperamental Bob Caruthers, from whom Foutz was now long estranged.12 Another party joining Foutz there was his new bride, the former Minnie M. Glocke of Philadelphia. The couple set up housekeeping in the City of Churches and appeared inseparable to observers. But the marriage would be childless and was doubtless strained by the mental illness that eventually required Minnie’s institutionalization.

Although largely bereft of the curveball that had kept enemy batsmen at bay, the crafty Foutz proved a capable spot starter for Brooklyn, going 12-7 with a 2.51 ERA in 176 innings pitched. Otherwise, he rotated between first base and right field for the second-place (88-52) club, batting .277, with 36 extra-base hits, 91 runs scored, and 99 RBIs. Dave also stole 35 bases. Caruthers, meanwhile, went 29-15, with a .230/5/53 slash line as a part-time outfielder.

With predecessor Dave Orr dispatched to Columbus, Foutz became Brooklyn’s regular first baseman in 1889 and had a banner year. His smooth play around the bag drew constant press praise, while his solid stickwork was much appreciated by manager Bill McGunnigle. Appearing in 138 games, Dave batted .275, with career highs in RBIs (113) and runs scored (118). He also stole 43 bases, and even chipped in a 3-0 pitching record as the (93-44) Bridegrooms (a new club nickname) nosed out the four-times defending champion St. Louis Browns for the American Association pennant. In recognition of his season’s work, readers of a New York weekly called Sports Times voted Dave “the best general player in the American Association.”13 The real key to Brooklyn’s success, however, was the yeoman pitching work of Bob Caruthers (40-11). But Caruthers was hit hard by the National League champion New York Giants in the postseason, and Brooklyn was denied a world title in nine games.

The baseball world was in turmoil as the 1889 interleague championship was being decided, and within weeks a new competitive rival was unveiled, the player-controlled Players League. Like other AA standouts, Foutz was mostly ignored by Players League recruiters bent on signing National League stars, and he later voiced disdain for the new circuit.14 But while Foutz was sticking with Brooklyn, his club was abandoning the financially troubled American Association. For the 1890 season, the defending AA champions would be a member of the National League.15

The switch in circuits had no effect on Brooklyn’s place in the standings, as the club came out on top in the talent-depleted National League. Foutz was again outstanding for the new champs, combining his dependable defensive play with potent swat: a .303/5/98 slash line, plus 43 extra-base hits, 106 runs scored, .432 slugging percentage, .801 OPS, and 42 steals. He continued his good work in the postseason, batting .300 with 4 RBIs as Brooklyn and the AA Louisville Colonels struggled to championship stalemate, the match abandoned with the games deadlocked 3-3-1 amid bad weather and fan disinterest.16

In the aftermath of the Players League’s demise at the end of the 1890 season, circuit mastermind John Montgomery Ward returned to the NL fold and assumed command of the Brooklyn club. Although he made lineup changes elsewhere, Ward retained Foutz as the Grooms’ regular first baseman. Playing through a midseason illness that doctors were unable to diagnose, Dave posted offensive stats (.257/2/73) that were subpar by his standards but befitted the lackluster (61-76) sixth-place team he played for. During the offseason, any thoughts that Foutz may have entertained about playing elsewhere – the AA Washington Senators had reportedly offered him a $4,000 contract17 – were rendered moot when the American Association folded over the winter. Returning to Brooklyn for the 1892 campaign, Dave endured a peculiar season. Manager Ward installed future Hall of Famer Dan Brouthers at first, with Foutz relegated to spot duty in the outfield and a semi-regular turn in the pitcher’s box. The results were mixed. Foutz’s batting plainly suffered, as he batted an anemic .186 in 220 at-bats. But despite presumed arm rust, he proved surprisingly effective at his erstwhile position, going 13-8, with a 3.41 ERA in 203 innings pitched, for a much-improved third-place (95-59) Brooklyn club.

During the offseason, John Montgomery Ward realized his ambition to return to former haunts in Manhattan and resume charge of the club that he had once captained, the New York Giants. Amid widespread approval, the vacant place at the Brooklyn helm was conferred upon Dave Foutz. Over the next four seasons, he would prove a competent but unaccomplished field leader, chronically handicapped by a placid disposition that made it difficult for him to assume the role of player disciplinarian. As the 1893 season began, the failing health of consumptive Darby O’Brien – he would succumb in mid-June – obliged manager Foutz to station himself in left field. He also played first on occasion. In 130 games combined, Foutz contributed a .246/7/67 slash line, with 91 runs scored and 32 stolen bases, to the cause, as Brooklyn (65-63) tied for sixth place and squeezed into the first division of the bloated 12-team National League, one game behind Ward’s Giants in the final standings.

The following season was a difficult one for the now 38-year-old player-manager. In the early going, he was troubled by colds and aches and pains, and suffered from near exhaustion.18 Thereafter, he was struck with “rheumatism in the neck,”19 often leaving the club in the hands of outfielder-captain Mike Griffin while he sought treatment. When available, Foutz remained a useful player, a slick-fielding first baseman and a decent hitter (.303 with 52 RBIs in 73 games). But Brooklyn’s progress under his command was only slight, the club posting a noncompetitive (70-61) fifth-place finish in 1894.

If 1894 had been a trying year for Foutz, 1895 would prove more so. At home, the deteriorating mental health of wife Minnie Foutz required her commitment to the insane asylum, where she would spend the remaining three years of her life. Another headache for Dave was his players, many of whom openly flouted team rules. Foutz also had quarrels with Griffin, and by midseason his removal as manager was being predicted in newsprint.20 But Foutz retained the confidence of club president Charles Byrne, and he soldiered on, the Grooms posting a third consecutive winning (71-60) but middle-of-the-pack finish under Foutz’s direction. For his own part, age, injury, and minor illnesses restricted Dave to 31 games in the field, but his .296 BA with 21 RBIs demonstrated that a degree of pop was left in his bat.

Contrary to prediction, Foutz returned as Brooklyn manager for the 1896 season, but the campaign would not be a happy one. Again, he had trouble controlling wayward players, and his quarrels with team captain Griffin continued. On May 14 Foutz placed himself in the lineup (right field) and went 1-for-4 in a 13-2 mauling by Cincinnati. It was his final major-league game appearance, bringing to a close a versatile playing career. As a pitcher, Foutz posted a sterling 147-66 record, with a 2.84 ERA, in just under 2,000 innings. To this day, his .690 career winning percentage remains second-highest among major-league pitchers with at least 100 victories.21 He was also a first-rate batsman and defensive player, particularly at first base. In 1,136 games, Foutz batted .276, with 308 extra-base hits and 750 RBIs to his credit.22 In 596 games at first, he posted a fine-for-the era .977 fielding average.

The Grooms finished poorly (58-73, tied for ninth place) in 1896, and Brooklyn co-owner Ferdinand Abell was clearly displeased with Foutz’s inability to maintain order in the ranks. At season’s end Abell declared, “Manager Foutz had very poor control over the men who did about what they pleased. If they wanted to violate club rules and discipline, they did so, and told the manager of the team to make the best of it.”23 Shortly thereafter, Foutz was replaced as Brooklyn manager by Billy Barnie. In his four seasons at the helm, Foutz posted a winning 264-257 (.507) record, but had never placed his club in pennant contention.

Foutz wanted to remain in the game, but not as a player. A deal to manage the Grand Rapids Gold Bugs of the Western League foundered on Foutz’s reluctance to play first base, as he feared the effect that physical exertion might have on his health.24 His resolve to continue solely as a nonplayer was then reinforced by a life-threatening bout of pneumonia that left him bedridden much of the winter. When he recovered, however, Foutz curiously applied for the physically taxing job of a National League umpire, and lobbied for the post in late February when the league conducted a winter meeting at Baltimore’s Rennert Hotel. A week later, Dave Foutz was dead, succumbing on March 5, 1897, at his mother’s home in nearby Waverly, the victim of an acute asthma attack.25 He was only 40. The unexpected passing of the well-liked Foutz stunned the baseball world and tributes quickly poured in. Typical were the sentiments of Baltimore sportswriter Albert K. Mott: “A very kind-hearted player has gone to his rest. Dave was a favorite of everybody. … He was exceptionally moral. He was a good fellow. He will be sincerely mourned by every person who ever came under his kindly influence.”26 New York scribe John B. Foster wished, “Peace to his ashes. He was a kind, simple-hearted man who never did anyone an evil turn, and always spoke well of his fellow man.”27

Following funeral services at the Foutz family residence, the deceased was interred at Loudon Park Cemetery in Baltimore. In addition to kinfolk and friends, attending at graveside was a contingent of Brooklyn players headed by club president Byrne, who eulogized Dave Foutz as a “quiet, honest, and conscientious man and one of the greatest ballplayers the country has produced.”28 Survivors included ill and confined wife Minnie (who would die the next year), his mother, Miriam, and nine siblings, including 19-year-old Frank Foutz, himself about to embark on a lengthy professional ballplaying career that would include a brief stint with the 1901 Baltimore Orioles.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information provided herein include the Dave Foutz and Frank Foutz files maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; Foutz family information posted on Ancestry.com; the profile of Dave Foutz by Robert L. Tiemann published in Nineteenth Century Stars, Tiemann and Mark Rucker, eds. (Cleveland: SABR, 1989); “Farewell Foutz,” an article about the early baseball career of Dave Foutz by grandnephew John C. Behlert published in The National Pastime, Number 22 (2002), 77-80, and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. Statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference and Retrosheet.

Notes

1 The other Foutz children were John (1855-1928), Evelyn (1859-1905), Margaret (1860-1938), Joseph (1862-1865), Hervey (1865-1948), William (1869-1951), Elizabeth (1871-1962), Stanley (1874-1963), Frank (1877-1961), and Howard (1879-1967).

2 The Foutz (originally Pfautz or Pfoutz) side of the family descended from Bavarian immigrants who arrived in the [then] American colonies of Great Britain in the early 1730s. The Cooks came from English settler stock. Both the Foutz and Cook clans took up residence in the Baltimore area in the 1750s.

3 As per John C. Behlert, “Farewell, Foutz,” The National Pastime, Number 22 (2002), 78.

4 John Foutz was a catcher of some ability and, at 6-feet-3, 141 pounds., was even spindlier than Dave. In 1889 John Foutz captained the Leadville Blues to the championship of the independent Colorado State League. He also became one of Leadville’s leading merchants.

5 According to his grandnephew, Dave won the only two games he pitched for Leadville in a three-game $2,500 match. Later, he won five of six games pitched against Salt Lake City in a $5,000 rematch. Behlert, 78.

6 Behlert, 78. The Foutz profile in Nineteenth Century Stars puts Dave’s log at 40-1.

7 As recalled in an item from the Grand Rapids (Michigan) Democrat reprinted in The Sporting News, March 20, 1897. Early in his major-league career, Foutz’s skills as a card sharp would lead to years-long estrangement from St. Louis pitching partner Bob Caruthers, as reported in Sporting Life, December 9, 1885, and February 22, 1888. Like many other players of his era, Foutz was also fond of the racetrack.

8 While pitching for Bay City, Foutz had been scouted by Browns owner Chris von der Ahe, who agreed to a hefty $2,000 purchase price for Foutz’s contact. Von der Ahe also gave Foutz a $1,600 salary for the remainder of the 1884 season, per Tiemann, 47. In the baseball circles of the day it was widely believed that the then 27-year-old Foutz was only 22.

9 A dispute over a second game forfeit awarded to Chicago produced hard feelings and led to the indecisive outcome.

10 As subsequently reported in Sporting Life, February 11, 1893.

11 Sporting Life, October 10, 1893.

12 See again, Sporting Life, December 9, 1885, and February 22, 1888.

13 An unidentified commentator adjudged the laurel more a reflection of Foutz’s fan popularity, and declared, “(T)he less said [on the vote’s merits] the better.” Sporting Life, February 12, 1890.

14 During the 1890 season, Foutz was an outspoken critic of the Players League, disparaging its financial stability. See Sporting Life, May 17, 1890. Thereafter, in response to rumors that he would jump leagues the following season, Foutz declared, “Why would I leave the Brooklyn club with which I am entirely satisfied to join the Brotherhood club? More money? I am getting all the money I ask for from the Brooklyn club, and I get it twice a month. Oh, no! I guess I am pretty well off where I am,” Sporting Life, September 20, 1890.

15 The American Association replaced its bolting champions with a ragtag new franchise called the Brooklyn Gladiators that did not complete the 1890 season.

16 The final two games were played in Brooklyn in late October and drew less than 1,000 spectators combined.

17 According to Sporting Life, January 9, 1892.

18 As reported in Sporting Life, May 8, 1894.

19 See Sporting Life, July 11 and August 9, 1894.

20 See, e.g., Sporting Life, June 22, 1895. See also Cincinnati Times, September 14, 1895.

21 The all-time major-league pitching percentage leader is Spud Chandler (.717). Foutz’s .69014 is an eyelash better than Whitey Ford’s .69006, while Bob Caruthers (.688) ranks fourth.

22 In a shorter career that ended in 1893, Bob Caruthers went 218-99 as a pitcher, while batting .282 in 705 games. Foutz’s other rivals for the title of 19th-century playing versatility champ accumulated roughly similar numbers: Jack Stivetts, 203-132, with a .298 BA in 601 games; Guy Hecker, 173-137, with a .282 BA in 705 games.

23 Sporting Life, October 10, 1896.

24 As reported in Sporting Life, December 5, 1896, and the Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, March 6, 1897.

25 As reported in the Baltimore Sun and New York Times, March 6, 1897, and newspapers nationwide.

26 Sporting Life, March 13, 1897.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

Full Name

David Luther Foutz

Born

September 7, 1856 at Carroll County, MD (USA)

Died

March 5, 1897 at Waverly, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.