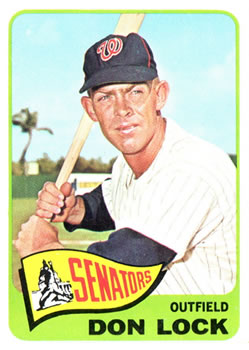

Don Lock

Don Lock was a strong defensive center fielder who twice placed in the top 10 in homers in the American League. He played in 921 major-league games from 1962 to 1969.

Don Lock was a strong defensive center fielder who twice placed in the top 10 in homers in the American League. He played in 921 major-league games from 1962 to 1969.

Lock was originally signed in March 1958 by New York Yankees scout Tom Greenwade, the same scout who signed Mickey Mantle. Greenwade signed Lock out of Wichita State in 1958 during his senior year, for a reported $12,500 bonus.1

Don Wilson Lock had grown up on a Kansas farm. He was born to John and Agnes Lock, their only child, on July 27, 1936, in Wichita. The Lock farm was in Valley Township, Kingman County. At the time of the 2010 census, the entire county had fewer than 8,000 inhabitants; Valley’s population was 102.

Lock attended Kingman public schools and Kingman High School, where he played basketball, football, and track, lettering in basketball and football. In 1951, he had played a year of American Legion baseball, and he played two years of semipro ball in 1954 and in 1957 for the Boeing Bo-Jets. Lock was recruited to Wichita State by Ralph Miller and went to college on a basketball scholarship. He ultimately completed his degree in physical education but that was a result of studies in the offseasons. He lettered in basketball.2

It was baseball that he played professionally, though. Once signed, he got in a full season with the Northern League (Class C) Fargo-Moorhead Twins in 1958, appearing in 121 games and batting .257 with 78 RBIs and 13 home runs. The team finished second in the league, and won the playoffs.

Lock was a married man, having married Delores Kay Anthony earlier that year on March 14, 1958. He was listed as 6-foot-2 and 195 pounds. It had been quite a way to start the year: “In one week, I played my last basketball game, became a pro, got married, and went to the Yankee camp.”3

Between the 1958 and 1959 seasons, he sandwiched in six months’ service in the United States Army.

In 1959, Lock was moved up to the Class-B (Carolina League) Greensboro Yankees and put up distinctly better stats. In 133 games, he hit .283, hit 30 homers, and drove in 122 runs. The team finished fifth in the six-team league with a record of 54-76. Lock led the league in homers, RBIs, and runs scored, and managed not to get elected to the league All-Star team. He was, however, honored nationally by being named to Parade Magazine’s minor-league All-Star team.4

He also played nine games at Single-A Binghamton and was 7-for-24 at the plate.

In 1960 he played 136 games for Binghamton, seven for the Double-A Amarillo Gold Sox, and three for the Triple-A Richmond Virginians. He hit well under .200 at both of the higher levels, but where he got the most work was in Binghamton and he drove in 117 runs with 35 homers and a .262 batting average. Both the RBIs and homers led the Eastern League and this year he did get named to the All-Star team.

Working his way up the ladder, Lock spent all of 1961 with Richmond. His 29 homers set a club record at the time, though his batting average suffered (.236) and apparently not as many teammates were getting on board in front of him; he drove in 77 runs.

Lock was one of the last players cut from the big-league club at the end of spring training and he began 1962 with Richmond again, and was not playing well, batting only .194 after 73 games, with 32 RBIs. He did earn a headline at one point—by being hit in the face by a pitch on June 12, but was said to have been spared serious injury because of a “mammoth cud of chewing tobacco” in his left cheek.5

On July 11, the Washington Senators and the New York Yankees made a deal, one involving mutual waivers.6 The Yankees acquired veteran first baseman Dale Long on July 11, and sent Don Lock to Washington. Senators GM Ed Doherty said, “The Yankees didn’t want to give up Lock, but they were in a hurry to win the pennant and needed Long for pinch-hitting.” In terms of what he hoped the Senators would be getting, Doherty acknowledged that Lock had not yet achieved particularly impressive batting averages. “You must always credit the Yankees with liking a ball player their scouts sign, because they don’t sign him otherwise.”7 Lock had homered four times in the five games before the deal. Now he had his chance to make it to the majors.

One could argue that Lock’s first game in the major leagues was one of his best. He made his way to Chicago and played both games of a doubleheader against the White Sox on July 17. The first game was a scoreless tie after six innings. Lock led off the seventh and hit Juan Pizarro’s 0-2 pitch to left-center field for a home run that wound up winning the game, 1-0, thanks to a shutout thrown by Dave Stenhouse. Not too many players win a game like that in their debut game. Lock came in as a late-inning defensive replacement in the second game and struck out in his only at-bat. The next time he faced Pizarro, on July 25, he homered again.

Lock acquitted himself well, playing in 71 games and driving in 37 runs. The Senators finished in 10th place, 60-101. He homered 12 times.

After the season, he played for the Senators in Florida rookie league ball.

In late 1962, Senators manager Mickey Vernon said that he hoped for more from Lock in his first full season, 1963. He said he saw parallels to Harmon Killebrew and that Lock, too, could cut back a bit on his swing: “You don’t have to hit a home run 60 rows deep, one row is enough.”8 Newsday said, “Lock has always been plagued by the big swing — and the big whiff. It’s what kept him out of pin stripes. Finally, the Yankees got fed up with the wind and peddled Don to Washington in exchange for Dale Long.”9

The Senators were concerned with his strikeouts, too. New GM George Selkirk said, “Nothing kills a ball club more than a strikeout…I know that Lock runs well, is a good fielder and has a respectable arm. But he must cut down on those strikeouts.”10

Both in 1963 and 1964, Lock led the Senators in homers and runs batted in. The team, though, languished at the bottom of the standings, 10th again in 1963 and improving only to ninth in 1964. Lock was .252 with 27 homers and 82 RBIs in 1963 and a nearly-identical .248/28/80 in 1964.

His biggest day in 1963 was probably July 27, when he drove in five runs in an 8-4 win over the Tigers in Detroit. But by that time he also had the unusual distinction of having won three extra-inning games: on May 8 with a grand slam in the 13th, on May 12 with a solo homer in the 14th inning, and on July 19 with a 13th-inning single.

Lock led American League center fielders in putouts, assists, and double plays turned in 1963, and all AL outfielders in assists the following year.

After the season, new Senators manager Gil Hodges presented Lock with the team MVP award voted on by a local Senators fan club and said, “I don’t believe you could have chosen a better player for this award. He is on his way up and I look for better things from Don next year.”11

He had two five-RBI days in 1964, but both were in losing efforts. There were three games in which he homered twice and drove in four. One of those was a loss, too. His most singular contribution was one that had to be one of his most thrilling in baseball. It came on July 29 at D.C. Stadium. Lock’s first homer was a solo one, hit into the Senators bullpen off Sam McDowell of the Indians in the bottom of the sixth, tying the game 1-1. That score stood until Lock came up in the bottom of the 12th. Gary Bell was pitching in relief. There was one out and runners on first and second. Lock homered and won the game, 4-1.

The Grandstand Managers club again voted Lock MVP honors for his ‘64 season.

Everything sort of fell apart in 1965. He had a superb spring training, batting over .400 and leading the team in homers and RBIs, but that all changed as soon as the regular season began. He played in 143 games, but his RBI production dropped by more than 50%, to 39 for the full season. He only hit for a .215 batting average and hit 16 homers. Early in 1966, he said, “I was so bad last year I’m ashamed of myself…I don’t want to be mediocre.”12 He did get hit with about a 10% cut in salary for 1966. During the 1965/1966 offseason, he worked in a Kingman bank.13

Just as 1963 and 1964 had been similar years, so too were 1965 and 1966. In spring training 1966, he said, “They pay to see you hit homers, and I can hit them, Last season, I was disgusted with myself, I hit 16 homers. It would have been no trick to hit seven or eight more. You’ve got to bear down every minute in this game. That’s what I am going to do.”14

He didn’t.

He’d gotten off to a slow start. Right at the beginning of May, he said he was just going to stop thinking and worrying too much. “For 1 ½ years I’ve been experimenting at the plate. I’ve put my hands this way and that way and I’ve shifted my feet but nothing helped…All year I’ve been worrying about my hands and whether I was squeezing the bat too hard.”15 He had some standout days. On May 29, 1966, his first-inning homer drove in all three runs in a 3-2 win over the Red Sox, and on July 2 he had a 5-for-5 day with a homer against the Yankees. Bob Addie wrote about Lock in September: “When Don is going great, he looks like a combination of Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams and Ty Cobb. Lock has been not only sensational with the glove this year, but his bat has smoked and then has snuffed out.”16

In the end, he hit the same number of homers — 16 — and scored the same number of runs (52) both years. He also had the exact same number of base hits (90) but with somewhat fewer at-bats in 1966 so he improved in batting average (albeit only to .233). He ticked up from 39 to 48 runs batted in.

The Senators traded him on November 30, 1966, to the Philadelphia Phillies for left-handed relief pitcher Darold Knowles and cash. Senators manager Gil Hodges had been willing to overlook Lock’s typically low batting average and high number of strikeouts, because of his home run potential.17 In his best home-run years — 1963 and 1964 — he was second in the league in strikeouts. But the homers hadn’t come for a couple of years. Hodges said, “He puzzles you. You look at him some days and you think he’s finally arrived. You think he’s going to put everything together and be the outstanding player he should be. But then he falls right back into his old habits.”18 Phillies manager Gene Mauch said he sought Lock mostly for his skills on defense. “I understand no outfielder in the American League could go back on a ball better than Lock. We have a deep center field at Connie Mack Stadium and we have pitchers who pitch toward center.”19 For his part, Lock said as he drew on a cigarette, “I know I drive them nuts. They see a guy who can hit the ball a long way. But it’s feast or famine.”20

Mauch also added that Lock had “made some of his best fielding plays while in the throes of a slump,” saying, “A good player must use the leather when he can’t use the wood.”21

June 25 was Lock’s best day in 1967. He’d been going well and entered the day batting .300. In a doubleheader in St. Louis, he homered once in each game and drove in three runs in each game, having himself a 6-for-8 day. He was still hitting over .300 at the All-Star break, but hit under .200 the rest of the year, finishing with a few more RBIs (51), two fewer home runs (14), and a batting average of .252.

Lock was with the Phillies for the full year again in 1968 but didn’t play as much, appearing in 99 games. He had a very slow start and was still under .200 (without a single homer) at the end of June. He hit .210 for the season with 34 RBIs; he only homered eight times.

He just wasn’t in the Phillies’ plans come 1969, after they brought up Larry Hisle. Lock was on the big-league team but only had four at-bats in April and no more until he was traded on May 5 to the Boston Red Sox, for Bill Schlesinger. The Phillies got Schlesinger, who had only one major-league at-bat — and that had been back in 1965. He had grounded out to the pitcher.

At first, the Red Sox sent Billy Conigliaro back to the minors to make room for Lock, seen by at least one Boston sportswriter as “a good all-around player” who “will help the team.”22 He wasn’t going to get much playing time, behind Carl Yastrzemski, Reggie Smith, and Tony Conigliaro. Lock didn’t help the team much on offense. In 58 games, he accumulated 70 plate appearances but only drove in two runs. He hit one homer and for a .224 batting average.

Lock stayed in the Red Sox system, but never made it back to the big leagues. In 1970 he played in Triple A for the Louisville Colonels, hitting .237 in 99 games with 15 homers and 41 RBIs. That was his last year as a player.

In 1971, Lock managed Boston’s Single-A Carolina League team at Winston-Salem. The team finished 67-67. Lock assigned himself one at-bat, but was hitless. In 1972, he moved up to Double A and managed the Pawtucket Red Sox (Eastern League). The PawSox finished 61-79. For a part of the 1973 season, he managed the Wilson Pennants in the Carolina League, but there were no pennants for a last-place 52-88 team.

Lock’s father John had passed away in 1972, and Don decided to return to Kansas to operate the family farm. He did some scouting, and no doubt took in the National Baseball Congress tournament finals, held annually in Wichita. “He did a fair amount of speaking engagements for various groups,” recalled his son Deron in March 2018. “He also made contact with the Wichita State Alumni Association and he spent a fair amount of time doing things with both the baseball and basketball programs, going to their events.”23

“I have 1,800 acres,” he said in 1991. “I used to have cattle, but now I just have mostly wheat, soybeans, and corn. I’m my own boss,” he added, “but I really work for my banker.”24

After Lock lost his wife Delores in 2003, he sold off the family farm and moved to West Wichita. Deron Lock said, “My wife and I and our kids were in East Wichita and my sister and her three kids were in Ellsworth, so he had the opportunity to go to his five grandkids’ ballgames for years. That was a fun thing for him to do and for us to be around him. I read at his eulogy that he had gone to over a thousand ballgames with the grandkids. He tried to go to as many of those as he could.”25

Lock died of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) in Wichita on October 8, 2017. Fortunately, his son said, “He didn’t have other ailments at the time and was able to pass relatively quickly.” He left their son Deron Lock and daughter Dina Davis and five grandchildren.

Don Lock is an inductee of the Wichita State Basketball Hall of Fame, the Wichita State Baseball Hall of Fame, the Wichita Sports Hall of Fame, and was pleased to have been inducted into the Kansas Sports Hall of Fame in September 2017. Given all the halls of fame he was in, he must have looked back at his playing career with some degree of pleasure and satisfaction. “Oh, absolutely,” said Deron. “It was kind of the center of who he was. He knew tons of people because of it. He had stories forever and about things they did and places they went. He kept in contact with an awful lot of his friends, both from baseball and Wichita State. He always had a lot of friends around.”

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Lock’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com. Thanks to Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee.

Notes

1 Associated Press, “Yankees Sign College Player,” New York Times, March 11, 1958: 34.

2 Most of this information comes from a couple of questionnaires that Lock himself completed for the American League and later for the Boston Red Sox. The questionnaires are found in Lock’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

3 Sandy Grady,” Mauch Tries to Find Key to Don Lock,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, March 6, 1967.

4 “Thirty Players on Minor-League All-Star Team,” Atlanta Daily World, September 30, 1959: 5.

5 Associated Press, “Tobacco No Curse for Hit Batsman,” Washington Post, June 14, 1962: D3.

6 Bob Addie, “Nats Obtain Don Lock,” Washington Post, July 17, 1962: A18.

7 Shirley Povich, “Nats Lamp Lock as Key to Pickup in Homer Output,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1962: 12.

8 Ibid.

9 “Don Lock Is Trying to Curb His Enthusiasm,” Newsday, March 21, 1963.

10 Merrill Whittlesey, “Lock Gets Batting Advice In Return for Contract,” Evening Star (Washington DC), February 10, 1963: 77.

11 The fan club was known as the Grandstand Managers. See Ron Morris, “Nats’ Lock, Osteen Cited by Grandstand Managers,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1963: 34.

12 Bob Addie, “Lock Hopes to Forget Miserable 1965, But Refuses to Make Any Predictions,” Washington Post, February 27, 1966: C1.

13 Ibid.

14 Bob Addie, “Don Lock Sets Aim With Nats: More Homers,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1966: 23.

15 Tom Seppy, Associated Press release located in Lock’s Hall of Fame player file.

16 Bob Addie, “Lock and Ortega Key Trade Bait On Nats’ Shelf,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1966: 16.

17 In 1966, he struck out 126 times in 386 at-bats. Over the course of his career, he struck out in just under 29% of his at-bats.

18 Ed Rumill, “Lock Potential May Ripen with Phillies,” Christian Science Monitor, December 9, 1966: 21.

19 Ibid. Mauch said four clubs had been after Lock, including the Yankees. See Allen Lewis, “Phils Went High To Land Lock — Need Relief Ace,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1966: 32.

20 Sandy Grady.

21 Bob Addie, “Nats Cure 2 Pains With One Deal, for Pascual and Allen,” The Sporting News, December 17, 1966: 28.

22 Larry Claflin, “Lock Another Good Sox Move,” Boston Record American, May 6, 1969: 42.

23 Author interview with Deron Lock on March 12, 2018.

24 Skip Clayton, “Don Lock — Outfielder Was a Long-Ball Hitter,” Phillies Report, June 20, 1991.

25 Author interview with Deron Lock on March 12, 2018.

Full Name

Don Wilson Lock

Born

July 27, 1936 at Wichita, KS (USA)

Died

October 8, 2017 at Wichita, KS (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.