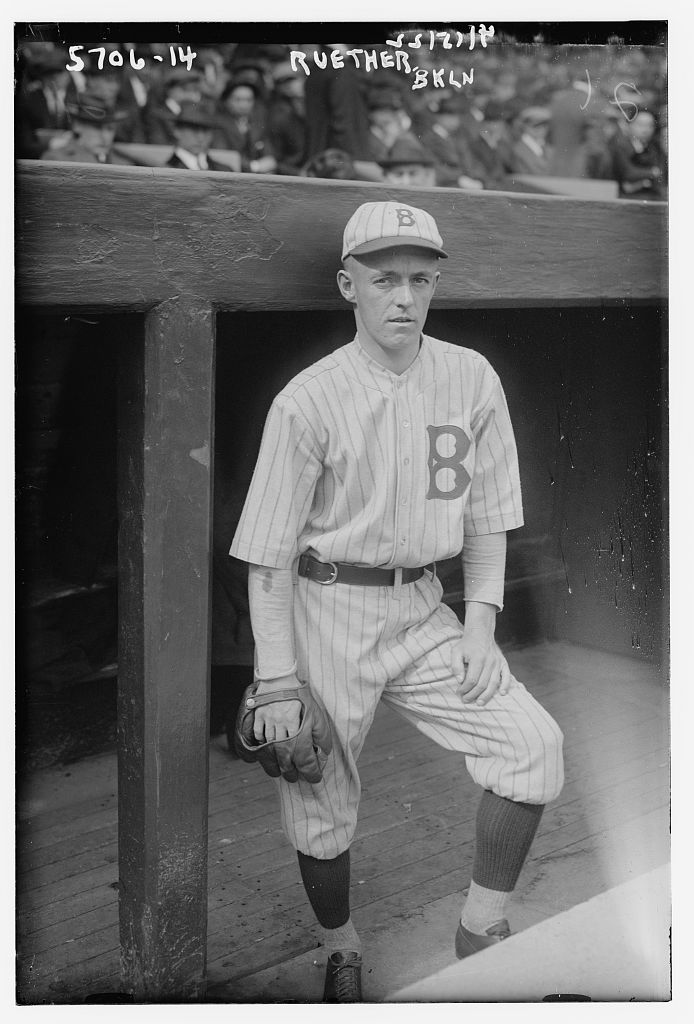

Dutch Ruether

His prep school coach almost kicked the youngster off the team, saying he was too hardheaded to ever make it as a ballplayer. The coach was wrong. Dutch Ruether had a long and successful career in professional baseball. He had a number of things in common with his future roommate, Babe Ruth, and outperformed the Bambino in some ways.

His prep school coach almost kicked the youngster off the team, saying he was too hardheaded to ever make it as a ballplayer. The coach was wrong. Dutch Ruether had a long and successful career in professional baseball. He had a number of things in common with his future roommate, Babe Ruth, and outperformed the Bambino in some ways.

Walter Henry Ruether was born on September 13, 1893, in Alameda, California. He was youngest of the three children of Augusta (nee Sohlke) and Frederick Ruether, German immigrants. During Walter’s childhood his father was a partner in a cigar manufacturing enterprise in San Francisco. Later he worked for an import-export company, also in the City by the Bay.

Walter grew up in San Francisco and tried out for the baseball team at the city’s St. Ignatius College Preparatory School,1 whose coach, George Hildebrand was a long-time American League umpire. After Hildebrand saw Walter pitch for the first time, he tried to give him some pointers, but the young man refused to listen. “Get out of here, you young hard-head,” the coach said, “You’ll never be a ballplayer as long as you live. You’re solid bone from your ears up.”2

The coach relented and kept the Dutchman, as Walter was called, on the squad. The kid was erratic, but he had an outstanding fastball. On March 10, 1913, Ruether pitched for St. Ignatius College against the Chicago White Sox in an exhibition game. He took a 2-1 lead into the ninth inning, but gave up a three-run home to Buck Herzog and lost the game, 4-2. However, his performance impressed professional scouts. The Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League offered him a contract, as did the major-league Pittsburgh Pirates. The 19-year-old southpaw signed with Pittsburgh for $900 on the condition that he could opt out of the deal if the Pirates assigned him to a minor-league club.

After a month at the Pirates spring training camp in Hot Springs, Arkansas, he was farmed out. So Ruether quit and returned to the West Coast to play in the Northwestern League.3 For several years he bounced around the West, playing for teams in Portland, Sacramento, Los Angeles, Vancouver, Salt Lake City, and Spokane by 1916. On September 15, 1916, the Chicago Cubs drafted him from Spokane in the Rule 5 draft.

On April 13, 1917, at the age of 23, the well-built (6-foot-1, 180 pounds) Ruether made his major-league debut, pitching a complete game masterpiece against the Pittsburgh Pirates, giving up six hits, two bases on balls, and one earned run, while striking out nine in the victory. He picked up one more win for the Cubs before they placed him on waivers. The Cincinnati Reds signed him on July 17, but he appeared in only seven games for the team before they lost him to the United States Army. He was assigned to Camp Lewis, near Tacoma, Washington, and missed all but two games of the 1918 season.

While he was in the Army, Ruether married Ethyle Patterson in Tacoma on May 11, 1918. She was a 21-year-old Scottish immigrant who had been in the United States for about three years and had a two-year-old daughter, Ruth. The marriage did not last; they were divorced before the January 14, 1920 census.

Ruether was discharged from the Army in time for Opening Day 1919, held as usual before a festive crowd in the Queen City. He started the Reds on their way to the pennant by defeating the St. Louis Cardinals, 6-2, although Adolfo Luque got credit for the victory in relief. The Reds won seven in a row, including one win by Ruether, before losing in St. Louis on May 2, by a score of 8-1. Ruether was the losing pitcher, but the defeat was not entirely his fault. He gave up only one earned run in five innings. Four errors led to four unearned runs and the Reds loss.

Ruether did not lose very many more games that season. He won 19 and lost 6, for a league-leading .760 percentage and an earned run average of 1.82. The New York Giants led the pennant chase most of the spring and summer, but the Reds caught them in early August and pulled away. On September 16, Ruether pitched the Reds to a 4-3 victory over the Giants, clinching Cincinnati’s first pennant since 1882, and the Reds were in their first-ever World Series. Manager Pat Moran chose Ruether to start the fall classic and the lefty cruised, winning 9-1. With the Reds leading four games to one in the best-of-nine Series, Ruether started Game Six for the Reds and pitched well for five innings, helping the Reds to a 4-1 lead, but he couldn’t get anybody out in the sixth, as the White Sox scored three runs to tie it up. Chicago then won the game, 5-4, in the tenth inning off reliever Jimmy Ring. Cincinnati lost Game Seven, then they wrapped up the Series in Game Eight. Their first World Series championship was marred by allegations that the White Sox has thrown the Series at the behest of gamblers.

The same fascination with “bad guys” that lead some people to idolize Jesse James and Billy the Kid has caused some modern writers to call the 1919 White Sox one of the greatest teams of all time and claim they would have been favored to beat a weaker Cincinnati club in an honest Series. Not so. The Reds had a better regular season record than did the White Sox and were not huge underdogs in the Fall Classic. There is ample reason to believe they could have won regardless of the fix.4

Ruether was incensed at the citing of his opening game triple against Eddie Cicotte as evidence that the Sox weren’t on the level. “Wotthehell,” he said. “I was a pretty good hitting pitcher. I was often called upon to pinch-hit and every once in a while there was talk of me becoming a first baseman when my arm gave out. I hit a double off Dickey Kerr later in the Series, and everybody knows Dickey was straight as a string. . . . . Miller Huggins used me as a pinch-hitter seven years later in a World Series with the Yankees.”5 Actually Ruether hit two triples in Game One – one off Cicotte in the fourth inning and one off Grover Lowdermilk in the seventh. The Yankee manager did use him as a pinch-hitter in the 1926 World Series, not just once, but twice.

In 1920 Ruether was the Opening Day pitcher for Cincinnati for the second consecutive year, and for the second year in a row he got the Reds off to winning start. He defeated the great Grover Cleveland Alexander and the Chicago Cubs, 7-3. The Reds led off and on all summer, but fell behind after Labor Day and finished third behind Brooklyn and New York. After the season, the Reds made some changes in personnel. Ruether was traded to Brooklyn for the veteran Rube Marquard, even up, on December 15, 1920.

Ruether did not get off to a good start in Flatbush, posting a 10-13 record in 1921. On December 10, 1921, he married Gertrude Magnolia Palmer in Redwood City, California.6 The couple had one child, Walter Jr., born in 1923. 7

Ruether came back strong in 1922, with his only 20-win season. At 21-12 it was the most wins he garnered in any season in his entire major-league career. Over the next two years his performance weakened, and he fell out of favor with Brooklyn owner Charles Ebbets. However, Washington’s “Old Fox,” Clark Griffith, and their “Boy Manager,” Bucky Harris, must have realized that Ruether was still viable. The world champion Washington Senators purchased the lefty on December 17, 1924.

Ruether had an excellent year for Washington in 1925, going 18-7, and he pitched well the following season. He had a 12-6 record with the Senators on August 27, 1926, when he was traded to the New York Yankees for players to be named later (Garland Braxton and Nick Cullop.) In the remainder of the season he won two and lost three for the Yankees. In the World Series Ruether started one game against the St. Louis Cardinals, but was the losing pitcher as Jesse Haines shut out the Bronx Bombers, 4-0. Ruether was used twice as a pinch-hitter in this Series. In Game Two he grounded out against Grover Cleveland Alexander and repeated that performance against the same hurler in Game Six. There was no disgrace in going hitless against Ol’ Pete.

In 1927 Ruether had a nice season for the Yankees, despite rooming with Babe Ruth. Ruth was surely not have been a good influence on the pitcher, who shared his love of the nightlife.

They also had other things in common. Both started their major-league careers as left-handed pitchers. Ruether won more games (137) than did Ruth (94), but only because the Babe spent most of his career as an outfielder.

Only Cy Young, Babe Ruth, and Dutch Ruether have ever pitched and tripled in a World Series game. Dutch is the only one who hit two triples in the game.

Both had reputations as carousers and heavy drinkers. Ruether reportedly liked the nightlife, and newspapers frequently called him a playboy. It is said, “he enjoyed taking a nip or two or three or four.”8 He got into more trouble with management for his behavior, but only because Ruth’s managers cut him more slack. Could anyone out-carouse, out-play, or out-drink the Babe?

The Yankees had reportedly agreed to pay Ruether a $2,500 bonus if he won 15 games during the 1927 season. According to the report, he had earned 13 victories by September 1. In order to avoid paying the bonus, the Yankee ownership ordered Huggins not to use Ruether in any more games. Angered by this treatment, Ruether quit the Yankees and returned to the Pacific Coast League.9

There may have been some truth to the report, but several details are inaccurate. Ruether had won 12 games, not 13, by September 1. After that date he made three starts, pitching complete games in all three. On September 6, he lost, 5-2, to the Boston Red Sox at Fenway Park. On September 14, he defeated the Cleveland Indians, 4-1, at Yankee Stadium for his 13th win of the year. On September 21, he lost to the Detroit Tigers at the Stadium, 6-1. He appeared in several more games, mostly as a pinch-hitter, and played in his last major-league contest on September 29, 1927, pitching three innings in relief. The Yankees released him, and his major-league career was over at age 34.

The Sporting News reported that Ruether seemed to be perfectly able to continue in major-league company for at least one more season, probably several more. But all clubs must have waived on him, because he became a free agent. Jack Hendricks, manager of the Cincinnati Reds, said he had no interest in bringing him back to Redland.10 Ruether’s liking for the bright lights had occasionally got him into trouble with his managers. Perhaps that accounts for the lack of interest in acquiring his services.

At any rate, Ruether was off to the Pacific Coast League in 1928. What a season he had for the San Francisco Seals! He won 29 games, while losing 7 for a winning percentage of .806. He was named the best pitcher in the league in the post-season selection of an all-star team. John McGraw expressed interest in drafting him for the New York Giants, but he wound up taking Tony Kaufmann instead.11

Ruether never made it back to the majors, although he tried. During spring training 1932, he applied for a job with Bucky Harris, who had been his manager in the glory days of 1925 and was now managing the Detroit Tigers. Harris told him he already had a full complement of pitchers.12

After his great 1928 season Ruether got in a salary dispute with the Seals and was given permission to make a deal for himself. He signed with San Francisco’s other team, the Mission Reds, much to the annoyance of the Seals.13 He had a good year with the Reds in 1929 (14-9, .609) but he never again approached the heights he had reached in 1928. He won 17 games for Seattle in 1930, but fell out of favor with manager Ernie Johnson in 1931. With a reputation for violating training rules, Ruether had not been keeping on the straight and narrow and was out of shape. He was soon on the move again. He finished the 1931 season with Portland; in 1932 it was Nashville, then Mission again. The Reds released him in February 1933, and he signed with Oakland as a pitcher and pitching coach. The Oaks credited him with the development of Lefty Gomez’s pitching style when both hurlers had been with the Seals, and they thought he could help their young pitchers.14

In 1934 Ruether accepted a position as player-manager of the Seattle Indians in the Pacific Coast League. Many minor-league clubs had a difficult time making ends meet during the depths of the depression. Even entire leagues folded. The Indians survived through the 1936 season before going under. Ruether told how the owner, Bill Klepper, once gave him all the gate receipts to hide from the sheriff, who came to the ballpark to collect back taxes due on admission fees. “I had all those damned dollar bills stuffed down my baseball pants, while I was coaching third base.”15

At the end of the 1936 season, Ruether’s career as a player or manager was over. At the age of 43, he was not through with professional baseball, however. He returned to the Los Angeles area and worked as a scout for the Chicago Cubs for seven years and for the Giants for 24 years.

Walter Henry Ruether died in Phoenix, Arizona, on May 16, 1970, at the age of 76. He was cremated, and the location of his ashes is unknown. The cause of his death was not included in his obituary in either The Sporting News or the New York Times. He was survived by his son, Walter Jr.

Notes

1 The boundaries between the prep school and the college (now called the University of San Francisco) were not clear. Ruether claimed he complete two years of college.

2 http://siprep.org/page.cfm?=6989.

3 Ibid. The accuracy of some of the St. Ignatius account is questionable. According to baseball-reference.com Ruether had pitched one game in the Pacific Coast League in 1911 and four games in that circuit before going to the Northwestern League in 1914.

4 See Charles F. Faber, “Winners of a Tarnished Crown; The 1919 Cincinnati Reds,” research paper presented to Pee Wee Reese Chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research, Louisville, Kentucky, June 12, 1994.

5 Tom Meany, Baseball’s Greatest Teams, (New York: A. S. Barnes, 1949), 162.

6 Gertrude was born in Illinois in 1894, the daughter of Edward Palmer, a carpenter. After two years of high school, she dropped out of school. In 1910 she was living in Los Angeles with her widowed father and working as a milliner’s apprentice.

7 The 1930 census reported that Walter’s 14-year-old son, who had been born in New York, was living with him and Gertrude. No other information about Frank can be found.

8 http://siprep.org/page.cfm?=6989.

9 http://siprep.org/page.cfm?=6989.

10 The Sporting News, December 1, 1927.

11 Ibid., October 11, 1928.

12 Ibid., February 25, 1932.

13 Ibid., March 28, 1929.

14 Ibid., February 2, 1933.

15 historylink.org/index.cfm?displaypage=output,cfmd.file_id=7566.

Full Name

Walter Henry Ruether

Born

September 13, 1893 at Alameda, CA (USA)

Died

May 16, 1970 at Phoenix, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.