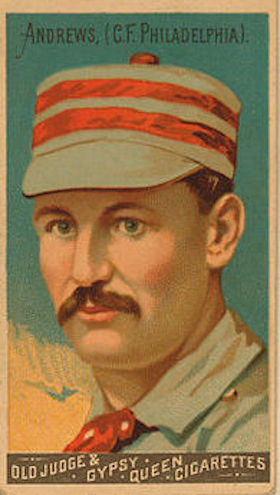

Ed Andrews

Born on April 5, 1859, in Painesville, Ohio, a small town that lies just east of Cleveland, George Edward Andrews, like many players in his time, went by his middle name. In most other ways, Andrews was a rarity in his or any other time: a model player who later became a model citizen and a highly respected spokesman for the game. With the assistance of Mike “King” Kelly (in all likelihood unwitting), he also orchestrated the denouement of his major league career so that he was able to depart at age 32 after one of his infrequent good games with Kelly’s Cincinnati Killers in his final season. It came on July 26, 1891, when Andrews played left field and went 2-for-3 in a 9-5 loss to Jo Meekin of the Louisville Colonels to lift his batting average for that season from .207 to .211, a figure 46 points below his .257 career batting average, which might seem a mark of mediocrity, especially for a player who spent most of his career as an outfielder, but in his case was highly unrepresentative of his true value.

Born on April 5, 1859, in Painesville, Ohio, a small town that lies just east of Cleveland, George Edward Andrews, like many players in his time, went by his middle name. In most other ways, Andrews was a rarity in his or any other time: a model player who later became a model citizen and a highly respected spokesman for the game. With the assistance of Mike “King” Kelly (in all likelihood unwitting), he also orchestrated the denouement of his major league career so that he was able to depart at age 32 after one of his infrequent good games with Kelly’s Cincinnati Killers in his final season. It came on July 26, 1891, when Andrews played left field and went 2-for-3 in a 9-5 loss to Jo Meekin of the Louisville Colonels to lift his batting average for that season from .207 to .211, a figure 46 points below his .257 career batting average, which might seem a mark of mediocrity, especially for a player who spent most of his career as an outfielder, but in his case was highly unrepresentative of his true value.

In a long letter to The Sporting News on November 2, 1896, among other things Andrews eloquently detailed how he came to make baseball a temporary profession that grew into one that consumed nearly a full decade in his life. In the spring of 1883, the 5’8” and 160-pound Andrews was still attending Western Reserve University and playing amateur ball in Cleveland when he passed his 24th birthday, an advanced age still to be in the amateur ranks for anyone who harbored aspirations of carving a lasting notch in the game. After the college term ended, Andrews played with the independent Akron, Ohio, team awhile and then traveled to Toledo, where he had friends on the Northwestern League club, to help out when the minor league alliance played an exhibition game with the Providence Grays of the National League. Andrews did so well that afternoon at third base that he was not only asked unavailingly to stay with Toledo by player-manager Charlie Morton, but after the game he was also invited by Providence skipper Harry Wright to have a serious talk about his future in baseball. Over dinner that night Wright revealed that he planned to manage the Philadelphia National League team in 1884 and proposed signing Andrews to a Philadelphia contract. Andrews said that he had no intention of playing ball full time but agreed that if he changed his mind Wright would be the beneficiary. After mulling it over for a few months, Andrews accepted Wright’s offer. When he arrived at the Philadelphia park in 1884 for preseason training, he found some 30 players milling about, no two in the same uniforms. “Some in rags, some in tags, and some in velvet gowns,” Andrews later described in his 1896 letter, but no sooner did Wright arrive than he quickly organized the motley group into an orderly workout. Andrews won the Quakers’ second base post in spring practice (no great feat on a team that had finished a bad last the previous year) and made his major league debut on May 1, 1884, at Philadelphia by batting last and going 2-for-4 in a 13-2 win over Detroit’s Stump Weidman.

Wright and Andrews remained close until Wright’s death in 1895. In his lengthy letter to The Sporting News, Andrews confided that early in his career in a game against Detroit he had cut third base when he had seen umpire John Gaffney’s back was to him. As Andrews took a seat on the Philadelphia bench after scoring, Wright reproachfully said, “Ed, I don’t want any games won that way,” and Andrews claimed he never again did anything that deceitful on the ball field while playing for Wright. Andrews also revealed that in the early weeks of 1890 he had been delegated by John M. Ward, the Players League’s principal organizer, to approach Wright and convince him to manage the Philadelphia Player’s League team. But when he went to Wright’s home he left empty-handed after Wright wished him and the Brotherhood every success but said he was committed irrevocably to the National League.

Andrews spent his first five and a half seasons in the majors under Wright and was a regular from Day One until he lost his job in 1889 after the Quakers acquired hard-hitting Sam Thompson from the defunct Detroit club. Used exclusively at second base in his rookie year, the right-handed Andrews began 1885 still at the keystone sack but shifted to the outfield on May 8 to make room for newcomer Al Myers. The move appeared to agree with Andrews; all through May his bat was so torrid that when the National League averages were published in Sporting Life after the games of May 27 he led the loop with a .431 mark. Over the remainder of the season Andrews’s average cooled down to a modest .266. The following year Wright batted him leadoff to take advantage of his speed, but while Andrews led the league in steals with 56 in the initial National League season that stolen bases became a recorded statistic, he neither hit nor walked enough to justify the move to the table-setter slot on almost any other team but Philadelphia.

By 1886 Wright’s club was built almost completely around players like Andrews: good at everything but hitting. After working out that winter in Jacksonville, Florida, however, Andrews led all Quakers regulars in both batting average and slugging average in 1887 with marks of .325 and .422, respectively. His defense and fine baserunning likewise made him a player in great demand. After the season, Andrews told a Philadelphia reporter that he had not been reserved by Philadelphia in 1887 and had agreed to play for $1,800, which was $200 less than he’d received as a rookie in 1884, only after Wright had promised to take care of him if he had a good year. Andrews then revealed that he wanted $5,000 and held out until March 1888. With a college education and a good offseason job as a salesman, he was in a stronger position than most players to demand the salary limit for that season, and other teams were eager to purchase him. However, the Quakers, suspecting tampering, particularly by Detroit, and probably regarding his holdout as a form of blackmail, were in no hurry to sell him. They would discuss only extravagant terms, offering him to Boston for third baseman Billy Nash plus several thousand dollars in cash and suggesting a trade for Hardy Richardson, arguably the best all-around player on Detroit’s pennant-winning team. In late March, the Quakers finally concluded that Andrews meant it when he said he would sit out rather than play in Philadelphia again and agreed to sell him to Boston if that team could come to terms with him. The complicated three-sided negotiations finally broke down, with Andrews rejoining Philadelphia and the Boston management left angry at what they regarded as a breach of faith. Andrews signed for considerably less than his asking price but still got $2,400, a substantial sum for the day.

In 1888, despite the ill will between Andrews and the Quakers front office, he led the team in both hits and runs, but it was no great achievement as the Quakers posted just a .566 team OPS. Indeed, Andrews’s individual OPS was only .569, a mere three points above the team average, and the lowest mark ever by a leader in both hits and runs on a major league club that played its full quota of scheduled games. His stolen bases fell off sharply to 35, and withal his season gave comfort to those who believed marriage was bad for a ball player; in July 1888 Andrews had wed Mary Kirby, the daughter of Dr. Edmund Kirby, a noted Philadelphia prohibitionist, and begun to lose some of his fascination with baseball. His disenchantment grew when Sam Thompson’s arrival from Detroit relegated him to the bench in the spring of 1889. Andrews’s services even as a substitute were so little needed that after he refused to be sold to Washington he was allowed to go home to Ohio and continue to draw his salary. Finally a sale more agreeable to Andrews was arranged with Indianapolis on August 16 and he supplanted Marty Sullivan in center field. In his first game back at full duty, even though Indianapolis lost 10-3 to Chicago, Andrews had personal reason to celebrate as he went 3-for-3 and followed by keeping his average around the .300 mark for the next two months before finishing at .302. The August 28, 1889, Sporting Life, illustrated an interesting rationale for arranging a batting order that took full advantage of Andrews’s strongest assets when the Indianapolis correspondent, Albert Owens, remarked that the recent acquisition Andrews was an excellent base coacher, and as a result manager Jack Glasscock had dropped himself in the batting order so that either Andrews, Glasscock himself or Jack McGeachey would always be available to coach the bases.

Andrews’s return to form not only reinvigorated his interest in the game but also made him attractive to Players League organizers and especially Ward, its prime mover. Andrews put his education to use by writing much of the publicity material at the time of the PL’s organization and signed with Ward’s Brooklyn club, joining the two outfielders that had flanked him when he occupied center field with Indianapolis, Emmett Seery and Jack McGeachey. But the trio doomed Brooklyn to be an also-ran in the 1890 Players League race when they logged the worst offensive numbers of all the regular outfielders in the league with the lone exception of Larry Twitchell. Andrews’s offensive decline continued in 1891 after he joined Mike Kelly’s last-minute American Association entry, Cincinnati Kelly’s Killers. In the April 25, 1891, issue of The Sporting News he tried to attribute both his poor start and also the team’s to a flu epidemic that had nailed several key members of the club in April, but the excuse failed to fly when the club showed no improvement after the epidemic subsided.

Andrews’s departure from Cincinnati was greased by a peculiar falling out with Kelly, who had deputed Andrews to run the team whenever Kelly was out of the game. During a July road trip Kelly left the team, and with business manager Frank Bancroft also away, Andrews was fully in charge. Upon taking command, he told reporters that Kelly two days before had confided to him that he was going to take a vacation. Andrews at first thought Kelly was joking, but Kelly really did leave for a brief spell and Andrews said he had no idea where the manager had gone. Andrews expected him to return, but the sudden departure fueled rumors already circulating that Kelly might want to take advantage of the ongoing trade war between the AA and NL to jump to the NL. A few days later Kelly resurfaced, saying he had only taken time off to rest an injury and was furious at Andrews for stirring up trouble. After that, Andrews was persona non grata with Kelly. Before the month was out, he was released to make way for journeyman Lefty Marr in right field. Marr was expected (wrongly as it turned out) to give the Killers the hitting they lacked, but observers believed that was not why Andrews was let go. As the Cincinnati Times Star put it upon learning of his exit, he fell out of favor because “he didn’t know where Kel was, and when he was asked he told the truth and said so.”

Andrews went home to Painesville, Ohio, and averred for the rest of the summer that he was entertaining offers from several ML teams. Whether or not there was any truth to it, the December 5, 1891, issue of The Sporting News said he was now ensconced on his new plantation in Eden, Florida, adjacent to the Indian River. His baseball career was over. The buyer’s market for talent that emerged from the combination of the NL and AA into a single 12-club major league was particularly unpropitious for an aging player like Andrews, and the diminished salaries teams were paying would not have tempted a man who had much better career prospects than the average ballplayer.

Consequently, although he took time on occasion to umpire in the majors and even began the 1899 season as a regular NL official before resigning on July 5, Andrews was one of the relatively few players who retired for good and never attempted to come back. He remained a resident of Florida’s East Coast for the rest of his life, eventually settling in Palm Beach, where he became a wealthy real estate developer. A skilled stenographer and typist, he carved a subsidiary career as a yachting writer and was known to both his readers and Palm Beach neighbors as “Captain George Andrews.” He died of a heart attack at age 75 on August 12, 1934, at Palm Beach Hospital in West Palm Beach.

Sources

An earlier form of this biography written by the author with assistance from the late David Ball appeared in Major League Baseball Profiles: 1871-1900, Vol. 1. The sources used in its preparation were Sporting Life (1883-1915) and The Sporting News (1886-1934).

Full Name

George Edward Andrews

Born

April 5, 1859 at Painesville, OH (USA)

Died

August 12, 1934 at West Palm Beach, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.