Eric Davis

In a 1987 Sports Illustrated article on teammate Eric Davis, Cincinnati Reds outfielder Dave Parker said, “Eric is blessed with world-class speed, great leaping ability, the body to play until he was 42, tremendous bat speed and power, and a throwing arm you wouldn’t believe.”1

In a 1987 Sports Illustrated article on teammate Eric Davis, Cincinnati Reds outfielder Dave Parker said, “Eric is blessed with world-class speed, great leaping ability, the body to play until he was 42, tremendous bat speed and power, and a throwing arm you wouldn’t believe.”1

Parker was right on all counts but one; Davis suffered far too many injuries and endured too much serious illness to allow him to play into his fifth decade. But he had all the tools, and when his body was right, he was one heck of a ballplayer. He had enough power and speed to earn membership in the 30-30 club — very nearly becoming the first 40-40 hitter — and was a good enough center fielder to earn three Gold Gloves during his career. He won a World Series with Cincinnati in 1990, but later in his career defeated a far more ruthless and dangerous opponent, colon cancer.

Eric Keith Davis was born on May 29, 1962, in Los Angeles, one of three children born to Jimmy and Shirley Davis; his siblings include an older brother, Jim Jr., and a sister, Sharletha. Eric’s father worked for Boys Market, a grocery-store chain. The family lived in very tough South Central Los Angeles, and Jimmy would go to the playground with his sons not only to shoot hoops, but to protect them from the dangers that lurked in the neighborhood. On one occasion, someone at the playground was shooting a gun wildly.

“Here I was, there to protect Eric, but the shooting was so close, I panicked,” said Jimmy.“ All I could say was just, ‘Eric, hit the dirt.’ We all ran behind the school. That’s the kind of area it is. It’s a blessing he got out without getting hurt.”2

It wasn’t unusual for kids in that area to be enticed into the drug culture. Davis was often offered narcotics as a youngster, but avoided the trap of addiction by playing sports. He played baseball and basketball at Fremont High School and often went up against childhood friend, rival, and future major leaguer Darryl Strawberry, who played at Crenshaw High School. Davis’s favorite sport was basketball, and he never took baseball seriously until his senior year in high school, when he hit .531 with 50 stolen bases. Numbers like those tend to draw scouts’ attention; it was at that point that baseball superseded basketball as a career path.

“I guess the first time I took baseball seriously was when the scouts started paying attention to me,” said Davis, who played shortstop in high school. “Darryl (at Crenshaw) always had more scouts watching him. There weren’t too many scouts who would come down to Fremont looking for talent.”3

A few teams did scout Davis, including the Dodgers and Brewers, but it was the Reds who signed him after selecting him in the eighth round of the June 1980 draft. His first stop was up the coast with the Eugene Emeralds of the short-season Northwest League. He didn’t set the world on fire immediately, hitting only .219 in 33 games as an 18-year-old.He hit only one home run, but he made it count — it was a two-run walk-off blast in the bottom of the ninth against the Central Oregon Phillies on August 18.

Davis worked his way up through the minors showing an impressive combination of speed and power; the power was especially surprising because although he was 6-feet-2, he played at only 165 pounds. He hit 48 home runs and stole 141 bases between 1981 and 1983, earning him a place on the Reds’ 40-man roster prior to the 1984 season. The Reds also decided to take advantage of Davis’s speed for defensive purposes by switching him from shortstop to the outfield, beginning in 1981 at Eugene.

Being on the 40-man roster doesn’t guarantee a trip up north with the big club, and such was the case with Davis, who began the 1984 campaign with the Wichita Aeros, Cincinnati’s affiliate in the Triple-A American Association. But sometimes you have to get a break to succeed; in Davis’s case, a hamstring injury to Duane Walker on May 17 earned Davis his first call-up to the majors. That Davis was hitting .311 with 10 home runs and 35 RBIs on the farm didn’t hurt.

Even as a rookie, Davis showed that he could both do magical things on a ballfield and lose playing time due to injury. The injury occurred when he hurt his knee sliding in a July 19 game against the Mets. He was benched for a while in the hopes that the injury would improve but the team finally put him on the disabled list on August 14. He returned on September 1 and celebrated by hitting five home runs in four games.

As impressed as he was by Davis’s power outburst, Reds manager Pete Rose was more concerned that he make contact rather than just aim for the long ball. “I told him to just be quick with the bat and the homers will come,” Rose said. “I told him, too, that I’d be watching him like a hawk. The kid understands. He has a chance to be the best player on this club.”4

Maybe the kid didn’t understand as much as Rose thought. He went north with the team after spring training in 1985 and turned some heads on Opening Day when he stole second and third on successive pitches during the Reds’ 4-1 win over Montreal. From that point on, about the only thing Davis turned was Rose’s stomach, for by June 4 he was hitting only .189, with 31 strikeouts in 90 at-bats. That’s when Rose sent Davis down to the Triple-A Denver Zephyrs, where he hit .277 in 64 games with 15 home runs, 38 RBIs, and 35 steals. The Reds recalled him in September, and Davis remained with the parent club the rest of the year. He admitted that returning to the minors was good for him. “The only thing good about going back was that it helped me mentally,” he said. “It was a test of my character, especially when I failed after all the media hype last spring.”5

Davis made the parent club again in 1986, when the Reds left spring training with seven outfielders. Rookies Paul O’Neill and Kal Daniels won jobs in Florida to join holdovers Davis, Parker, Eddie Milner, Nick Esasky, and Max Venable. As he did the previous season, he impressed on Opening Day, belting a three-run homer to lead Cincinnati to a 7-4 win over the Phillies. Unlike 1985, however, he stuck around awhile and began exhibiting some of the power and speed that had Reds executives salivating.

Davis really began to prove himself when Esasky went on the disabled list on June 14 with sore thigh muscles. After starting 12 games in April, he had been benched in early May when he was hitting .214 with 4 home runs, 12 RBIs, and 17 stolen bases in 98 at-bats. He started sizzling as soon as he resumed a regular role, hitting .371 in his first 25 games after Esasky’s injury, with 8 home runs, 19 RBIs, and 23 stolen bases. The Reds lost anyway, 8-4.

Davis joined some select company on August 25, 1986, when he hit his 20th homer of the year, off the Pirates’ Rick Rhoden. The blast qualified him for entry into the exclusive 20-60 club (20 home runs and 60 stolen bases), joining future Hall of Famers Joe Morgan and Rickey Henderson. He eventually reached the 20-80 echelon, with 27 homers and 80 steals to go with a .277 batting average, 71 RBIs, and a .901 OPS.6

Davis credited batting coach Billy DeMars with his improvement as a hitter, because DeMars changed his approach at the plate, getting him to tighten up his swing and go with the pitch instead of trying to pull everything. This meant that instead of trying to hit an outside pitch to left (Davis was a right-handed hitter), he could hit it to right, and with authority.

The lessons Davis applied in 1986 worked even better in 1987. By the All-Star break he was batting .321, with 27 home runs and 68 RBIs, including three grand slams in May. Not surprisingly, he started in the All-Star Game for the first time, going 0-for-3. He started well in the second half; on August 2 he smacked his 30th home run of the season, making him the seventh player to join the 30-30 club (30 home runs and 30 stolen bases — he already had 37 steals). It seemed inevitable that Davis would become the first player ever to become a 40-40 man.7 But he went through a second-half slump, due in part to a rib injury he suffered on September 4 crashing into the outfield wall at Wrigley Field while taking an extra-base hit away from Ryne Sandberg. The injury also forced Davis to miss 17 of the team’s last 27 games. His numbers for the season were still very impressive: 37 home runs, 100 RBIs, and 50 stolen bases. After the season, Davis had to make room on the mantelpiece in his home because he won his first Gold Glove and Silver Slugger awards. There would be more to come.

Davis could kiss a 40-40 season goodbye early in 1988 as injuries and poor production led to a terrible start. After missing three games in mid-May with a hamstring injury, he entered the “can’t-win-for-trying” society when some people thought he was hurting the team by coming back too soon from the injury, less than a year after facing accusations of malingering.

“Yes, I’ve heard both sides,” he said. “I heard I don’t play hurt, and now I hear I shouldn’t play hurt. I know some of my teammates and the manager have said things, but not to me. They say it to the media.”8

By May 31 Davis was hitting only .220 with 6 home runs, 23 RBIs, and 15 stolen bases. These numbers were so far below what he had reached the previous season that speculation as to why was inevitable. An article in the Cincinnati Enquirer on June 7 cited an unnamed National League executive as saying that rumors were going around that Davis was using drugs. Reds GM Murray Cook, who was said to be offering Davis as trade bait, flatly rejected the allegations.

“My official response is that I won’t grace it with a reply,” Cook said. “I’ll say one thing, he’s handled it [the adversity of the season] well and very maturely.”9

That maturity manifested itself in a vastly improved performance spurred on, perhaps, by Davis’s intention to disprove the drug allegations. His bat got hot just as the weather did, and he finished the year with a .273 batting average, 26 home runs, 93 RBIs, and 35 stolen bases. He also suffered the dings and bruises of outrageous fortune, as he sustained a number of freakish minor injuries that forced him to miss games on several occasions during the season. He sat out four games (and was only a pinch-runner in a fifth) with a swollen elbow after the Giants’ Atlee Hammaker hit him with a pitch on June 17. He then celebrated Independence Day by bruising his knee after colliding with teammates Barry Larkin and Jeff Treadway while chasing a fly ball. He had to be carried off the field and missed three games.

After the season Davis met reporters for the first time since imposing a personal gag order on June 1. He explained that his bad start was more typical for him than the amazing start he had in 1987. “The way I started last year [1987], that doesn’t happen often,” said Davis. In a way, it was unfortunate, because that’s what people are going to expect me to do all the time.”10

Davis signed a one-year, $1.35 million contract, plus incentives, after stories in the media appeared about his wanting to be traded. Once the season started, he managed to avoid a visit from the boo-birds of unhappiness by getting off to a hot start By June 30 he already had 14 home runs, 49 RBIs, a .293 batting average, and a .919 OPS, but only four stolen bases. The numbers were particularly impressive considering he injured himself yet again, missing 14 games after tearing his hamstring in a 6-4 loss to the Expos in Montreal on May 2.

Davis continued to play well after returning from the injury, and was named to the National League All-Star team by manager Tom Lasorda. It was typical of Davis’s emotional roller-coaster-type season that even that bit of good news became mired in controversy. Davis’s contract called for a $55,000 bonus for being “elected” to the All-Star team, but he finished fourth in fan balloting with 810,744 votes. There seemed to be some confusion about the details, with his agent, Eric Goldschmidt, contending that Davis was entitled to the bonus regardless of how he made the team. The Reds eventually paid the bonus.

After the All-Star break, Davis was good until September 3, when he continued his habit of running into outfield walls, this time at Three Rivers Stadium in Pittsburgh, while catching a fly ball in foul territory. He missed four games with a strained wrist. None of these injuries prevented Davis from having an excellent season, with a .281 batting average, 34 home runs, 101 RBIs, and 21 stolen bases, earning him his second Silver Slugger award. He also stood out again defensively, winning his third straight Gold Glove.

The 1990 season was bittersweet for Davis. He signed a three-year, $9.3 million contract in the winter, then proceeded to have a horrible start to the season which included — you guessed it — yet another visit to the disabled list. He missed 23 games in April and May with a knee injury, and just never got on track. He finished the season with a .260 average, 24 home runs, a team-leading 86 RBIs, and 21 steals in 127 games. But this was a different year for the Reds, as new manager Lou Piniella led them all the way to a stunning four-game sweep of the Oakland A’s in the World Series. Davis played well in the first three games, batting .286 with one home run and five RBIs. Disaster struck in Game Four, in Oakland.

Playing in his typical all-out way, Davis dove after and missed a Willie McGee fly ball in the first inning. After the trainer came out to have a look at him, he finished the inning, but collapsed on returning to the dugout. His teammates carried him to the clubhouse, and he was taken to the hospital after producing a blood-filled urine sample. He was diagnosed with a lacerated kidney, and spent 40 days in the hospital. A controversy erupted when he took a private plane home to Cincinnati, because Davis expected the Reds to pay for it.

“My agent talked to [then GM Bob] Quinn and asked him and he said, ‘He’s making $3 million, let him get his own plane,’” said Davis. “So I did. Then I sent them the bill.”11 The Reds eventually paid it.

Davis’s doctor said he should take the entire 1991 season off, but he was on the field against the Astros on Opening Day at Riverfront Stadium. His 2-for-4 performance indicated that maybe his doctor was being overly cautious, but as the season progressed it was clear that Davis wasn’t 100 percent. By July 20 he was hitting .252 with 10 home runs, 26 RBIs, 13 stolen bases, and a case of chronic fatigue that shelved him for 27 games in August — this was his second stint of the season on the disabled list, after he missed 14 games in June with a hamstring injury — and never did play up to his capabilities. He appeared in only 89 games all season, hitting only one home run and driving in five runs after returning from the DL.

Despite his valiant effort in 1991, Reds brass determined that Davis would never again be the player he once was or could be, and on November 27 he was traded with pitcher Kip Gross to the Los Angeles Dodgers for pitchers Tim Belcher and John Wetteland. For Davis it meant going home and playing with his childhood buddy Strawberry.

“The reality is they felt I couldn’t perform any more,” said Davis. “The No. 1 thing about how I performed last year was I had a kidney torn in three places. They held me accountable for that.”12

It turns out the Reds were right. The much-ballyhooed reunion of the boyhood mates didn’t result in a comeback for either player. Strawberry’s personal problems and injuries limited him to 43 games in 1992, and Davis’s hell-bent playing style led to more injuries, including a broken collarbone and a shoulder injury requiring surgery that ended his season in early September. Davis played in only 76 games.

Davis was a free agent after the season and, perhaps hoping there was still some of the 1987 player left in him, the Dodgers signed him to a one-year, $1million free-agent contract for 1993, plus $5,494.51 for every day he was on the active roster.13 Well, as the saying goes, a million dollars doesn’t buy what it used to. Dodgers general manager Fred Claire almost cut Davis in May when he was hitting .211, but he held on to him until August 31, when he traded Davis to the Detroit Tigers for a player to be named later.

That player was John DaSilva, who pitched in a total of six major-league games. For what the Tigers got from Davis, it was a pretty fair exchange. He played 23 games for them at the end of 1993. In 1994 he was batting .186 went on the disabled list on May 23 with a pinched nerve in his neck. He was out for 57 games, then left the first game he started upon his return (on July 26) in the seventh inning with a pulled groin.

The 1994 season was cut short due to the players’ strike, but Davis would not have returned anyway. He underwent surgery for a herniated disc in his neck — his eighth operation in seven years — then called it a career at age 32 when doctors advised him of how extensive the damage was.

Davis spent 1995 in Los Angeles overseeing several businesses, including a PR firm, and working out. But along about October, when his two favorite teams, the Reds and Dodgers, met in the NLDS, the ol’ competitive juices started flowing and visions of a comeback started dancing in his head. Finally, on January 2, 1996, Davis signed a minor-league contract with Cincinnati that promised him $500,000 if he made the team.

Davis had a great spring and did indeed make the team. The year off and a lot of work with hitting coach Hal McRae brought back some of the old Davis. Granted, he had his annual trip to the disabled list, when he missed 11 games with bruised his ribs he suffered making a diving catch in Denver on May 25, but notoriously stingy Reds owner Marge Schott really got her money’s worth, as Davis went on to hit .287, with 26 home runs, 83 RBIs, and 23 stolen bases in 129 games. His homer and ribbie totals were second on the team behind Barry Larkin, and he was third in thefts. All in all it was a great season, culminating in Davis’s winning the National League Comeback Player of the Year Award.

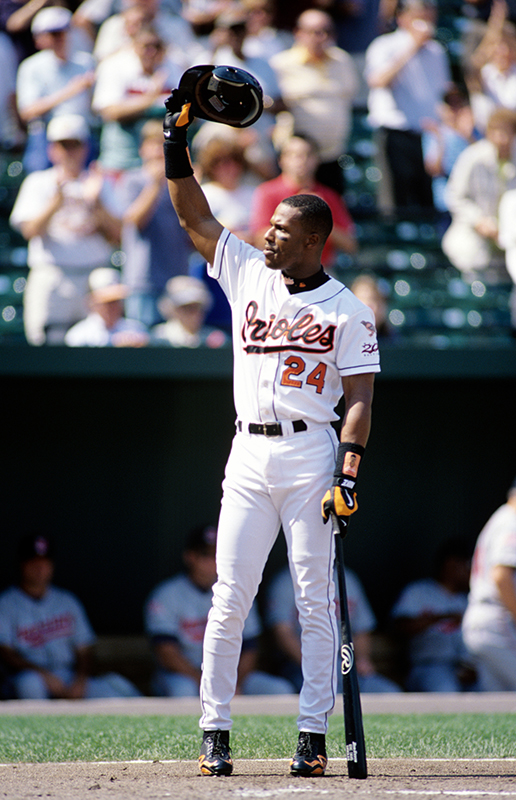

The Reds decided that even though Davis came back, he wasn’t going forward, and didn’t sign him for 1997. The Baltimore Orioles, on the other hand, were looking to replace Bobby Bonilla, who had left via free agency, and signed Davis to a one-year contract for $2.2 million with an option for 1998. He started the 1997 season off well, and was hitting .302 through May 25, when he had to stop paying due to a stomach ailment. That “ailment” turned out to be colon cancer, and he had a portion of his colon removed on Friday, June 13, at Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore.

The Reds decided that even though Davis came back, he wasn’t going forward, and didn’t sign him for 1997. The Baltimore Orioles, on the other hand, were looking to replace Bobby Bonilla, who had left via free agency, and signed Davis to a one-year contract for $2.2 million with an option for 1998. He started the 1997 season off well, and was hitting .302 through May 25, when he had to stop paying due to a stomach ailment. That “ailment” turned out to be colon cancer, and he had a portion of his colon removed on Friday, June 13, at Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore.

There were some who thought that Davis was a malingerer because of all the playing time he missed due to injury. Most were no doubt impressed by his 1996 comeback after missing more than a year because of his neck problems; certainly no one would begrudge him if he decided the hell with it after undergoing cancer surgery. But on September 15 Davis returned to the Orioles’ lineup, even while he was still getting weekly chemotherapy treatments, and helped them clinch the American League East title. He appeared in the ALDS victory over Seattle and the ALCS loss to the Cleveland Indians. Although he didn’t get a second World Series ring, Davis won the Roberto Clemente Award for being the most inspirational player, and the Fred Hutchinson Award, which is given to the player who best exemplifies character, dedication, and competitive spirit.14 In Boston, he was also honored with the Tony Conigliaro Award, presented annually to a player who has overcome an obstacle and adversity with spirit, determination, and courage.

“I was able to get operated on four days after I was diagnosed,” he said. “It was just a matter of getting this baseball-sized tumor out of me.”15

Davis returned to the Orioles in 1998, and after that season dictionaries could have put his picture beside the words comeback, courage, or determination — take your pick. He spent a lot of time as DH and none on the DL, and had a magnificent season: a .327 average (fourth in the American League), 28 home runs, and 89 RBIs. He also led the team with a .970 OPS.

The 1998 season was Davis’s last hurrah. He signed a two-year, $9 million deal with St. Louis, but the Cardinals didn’t get their money’s worth. His 1999 campaign was cut short after 58 games due to surgery to repair a torn rotator cuff, and he appeared in 92 games as a part-time player in 2000. He retired after playing in 74 games with the Giants in 2001.

Davis got involved in a number of business and baseball activities. He served as a roving instructor for the Reds, dabbled in real estate, and produced two documentaries. The first, Hitting From the Heart, is a motivational DVD that shows how athletes can overcome any obstacle to achieve their goals. The second, Harvard Park, is about how the park where Davis and Strawberry played in as kids produced so many great athletes despite being in a crime-ridden neighbourhood.

But Davis’s heart belonged to baseball. As of 2016, Davis was a special assistant to Reds general manager Dick Williams. He and his wife, Sherrie, had two daughters, Erica and Sacha.

Last revised: January 5, 2017

This biography appears in “Overcoming Adversity: The Tony Conigliaro Award” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Clayton Trutor.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used the following:

Websites

Cincinnati.reds.mlb.com.

Fredhutch.org.

UPI.com.

Newspapers

Orlando Sentinel.

Santa Cruz Sentinel.

Seguin (Texas) Gazette-Enterprise.

Star-Democrat (Easton, Maryland).

Books

Swaine, Rick. Baseball’s Comeback Players: Forty Major Leaguers Who Fell and Rose Again (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2014).

Notes

1 Ralph Wiley, “These Are Red Letter Days,” Sports Illustrated, May 25, 1887: 36.

2 Sam McManis, “South-Central L.A. Was Where It Began for Reds’ Eric

Davis — But Now, the Sky’s the Limit,” Los Angeles Times, February 2, 1987.

3 Ibid. That’s a surprising statement because the school also produced major leaguers Chet Lemon, George Hendrick, Bobby Tolan, and Bob Watson.

4 Earl Lawson, “Davis’ HR Binge Impresses Reds,” The Sporting News, September 17, 1984: 22.

5 Hal McCoy, “Davis Job-Hunting Again With Reds,” The Sporting News, April 7, 1986: 49.

6 Henderson was already in that elite group, having hit 24 homers with 80 steals in 1985. In 1986 he had 28 home runs and 87 stolen bases.

7 Jose Canseco of the Oakland A’s achieved the feat in 1988 with 42 home runs and 40 stolen bases. By his own admission, Canseco used steroids while playing. Davis, whose playing weight was 165 pounds, was never suspected of using performance-enhancing drugs.

8 McCoy, “Is an Injured Davis Hurting Reds,” The Sporting News, June 13, 1988: 25.

9 Michael Paolercio, “Davis: I Have No Drug Problem,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 7, 1988: C-1.

10 Greg Hoard, “Eric Davis Finally Has His Say,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 4, 1988: A-16.

11 Steve Dilbeck, “Davis Tells His Side of Incidents,’” San Bernardino County Sun, August 1, 1993: G5.

12 Joe Kay, San Bernardino County Sun, November 28, 1991: C7.

13 If the Dodgers were hoping that Davis would spend considerable time on the disabled list so they wouldn’t have to pay this particular bonus, they were sorely disappointed. He was on the roster all season.

14 Called the Hutch Award, it was created to honor Hutchinson by Pirates broadcaster Bob Prince. Hutchinson was the Reds manager when he was diagnosed with cancer in December 1963 and was given less than one year to live. He came back to manage the Reds in 1964, but had to stop in midseason. He died on November 12 of that year.

15 “Baseball Star Eric Davis’ Heroic Battle With Cancer an Inspiration On and Off the Field,” Jet, Volume 94, Number 16, September 14, 1998: 52.

Full Name

Eric Keith Davis

Born

May 29, 1962 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.