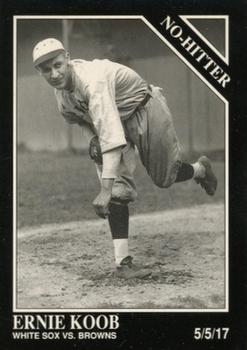

Ernie Koob

Southpaw Ernie Koob attracted national attention in mid-1915 by jumping from college to the big leagues with the St. Louis Browns. Less than two years later, the highly-touted curveballer tossed the first no-hitter by a Brownie in Sportsman’s Park, in 1917. But he never achieved the stardom many expected, compiling a 23-31 slate in parts of four seasons in the Gateway City.

Southpaw Ernie Koob attracted national attention in mid-1915 by jumping from college to the big leagues with the St. Louis Browns. Less than two years later, the highly-touted curveballer tossed the first no-hitter by a Brownie in Sportsman’s Park, in 1917. But he never achieved the stardom many expected, compiling a 23-31 slate in parts of four seasons in the Gateway City.

Ernest Gerald Koob was born on September 11, 1892, in Keeler, a small town in Van Buren County, in southwestern Michigan. He was the first child of John and Alice (nee Mikesell) Koob, followed by Lucille two years later; his mother had two other children (Percy and Bessie Abbott) from an earlier relationship. The Koobs were farmers and eventually established a fruit orchard in nearby Coloma, in Berrien County, a few miles from the shores of Lake Michigan. Ernie attended St. Joseph High School in the bustling coastal city of approximately 6,000 residents.

In the early 1910s, baseball was booming in southwestern Michigan, aided by the rise of the House of David, a religious commune in Benton Harbor, just north of St. Joseph. The sect became well known for its barnstorming team, whose opponents came from all over the region. By his late teens, Ernie was known as “Coloma’s young pitching phenom” and was a highly sought hurler by local semipro and town teams that dotted the landscape.1 In 1912, the portsider forged his reputation by striking out 23 against a visiting squad from Chicago. The following spring, he signed a contract offered by secretary Collier and manager C.M. Bloomfield of a semipro club in St. Joseph and his stature grew.2 In one noteworthy contest, the 20-year-old had “visitors looking exceedingly foolish and breaking their back going after his twisters,” gushed a report following Koob’s monumental 30-strikeout performance against the Washington Council team from Chicago in a 15-inning contest that ended in a 2-2 tie.3

Koob matriculated at Western Michigan University (then known as Western State Normal School) in Kalamazoo in the fall of 1913. After playing for the college nine, he began his professional baseball career in 1914 with the Kalamazoo Kazoos in the Class C Southern Michigan League. He played briefly and his statistics are incomplete.

Koob’s big break came the next spring when he was back with his college squad, coached by William H. Spaulding. In his first game of the season, Koob fanned 19 against Olivet College.4 On April 28, Koob’s team was in Ann Arbor to take on the University of Michigan, widely regarded the previous season as one of the best college teams in the country. As fate would have it, Branch Rickey, manager and general manager of the St. Louis Browns, as well as a graduate of the University of Michigan Law School and former coach of the baseball team (1910-1913), was at his alma mater on a scouting mission. Rickey’s protege, George Sisler, whom he had assisted earlier that year in extracting from a professional contract with Pittsburgh Pirates and would subsequently sign himself, faced off against Koob at Ferry Field. The two teams battled to a scoreless 10-inning tie; however, Koob emerged with the winning hand by striking out 10 and yielding just two hits in a distance-going outing.5 After three early-season games, Koob was unscored upon and had whiffed 49 batters while yielding just seven safeties. Wasting no time, Rickey signed the youngster on the spot.

Over the next several weeks questions arose about Koob’s status. According to the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, “scouts from practically all of the big-league clubs have been on [Koob’s] trail.”6 Reports emerged in May that both the Detroit Tigers and Philadelphia Phillies had made offers to Koob, and that the youngster had signed with the Tigers. In addition, the Battle Creek Crickets of the Southern Michigan League also claimed the pitcher’s rights and offered proof that they had already paid the player. The Crickets were skippered by Charles Wagner, Koob’s former manager with the Kazoos.

In a scenario similar to Sisler’s in January 1915, Koob’s fate was decided by the National Commission in Cincinnati. In early July, the three-person committee, which oversaw Organized Baseball before the sport had a commissioner, decided in favor of the Browns (by which time Koob had already appeared in a Browns uniform). Battle Creek, outraged by the decision, railed against Ban Johnson, the founding president of the AL and member of the commission, and disbanded its team in protest. The next day, July 7, the league folded, and the Koob decision was cited as the main reason.7

At the conclusion of his college season in 1915, Koob returned to Coloma, pitched some semipro ball in Benton Harbor, and reported to Rickey and the Browns in mid-June, his property rights still in question. The Post-Dispatch was hardly impressed upon seeing the 22-year-old, opining that “there is considerable doubt about Koob making good in the American,” given the yeoman task of jumping to the majors from college. 8 Standing 5-feet-10 and weighing only 150 pounds, Koob did not cut an imposing image on the mound, though the paper admitted that he “shaped up bigger in a baseball suit than one would think to look him over in the hotel room.”9 Koob, whose name rhymed with “robe,” had brown eyes and a tanned, yet reddish complexion, with a narrow head and square jaw, and “resembled a bank clerk more than a diamond hero,” noted Gateway City sportswriter Billy Murphy.10

The Browns were flirting with the cellar when Koob joined them. That was nothing new for the AL charter member, which had moved after just one season in Milwaukee to St. Louis in 1902. In its 15-year franchise history, the club had experienced a winning record just three times, the last in 1908. In his debut, on June 23, Koob retired the only two batters he faced against the Tigers in the Motor City. Five days later, Sisler made his mound debut for the Browns, as well, beginning his Hall of Fame career as a pitcher-first baseman-outfielder. Koob demonstrated he belonged on the big stage, tossing 7⅔ innings of two-run relief on July 16 against the Washington Senators and then holding the powerful Boston Red Sox to four hits and a run in eight innings of relief on July 22. Three days later, he earned his first start in the second game of a twin bill, also against the Red Sox, at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis and held the eventual pennant-winners to one run and four hits in seven innings in a game declared a tie, 1-1, after nine frames.

After he went the distance and held the Athletics to five hits and an unearned run at Shibe Park on July 29 to earn his first victory, 5-1, Koob’s name was plastered on sports pages across the country as the sensational schoolboy discovery of the summer. Billy Murphy of the St. Louis Star and Times praised Koob’s “cast-iron nerve, coupled with his excellent speed, a good curve ball and excellent control.”11 Starting and relieving the remainder of the season, Koob won only three more games, but they were doozies: a four-hitter against Boston at Fenway Park; a three-hitter against the A’s in St. Louis, and finally a complete-game 8-4 thrashing of pitcher Babe Ruth and the Red Sox in Boston.

The sixth-place Browns (63-91) were an awful club, outscored by 158 runs; however, Koob (4-5, 2.36 ERA in 133⅔ innings) and Sisler (4-4, 2.83 ERA in 70 innings and .285 batting average) emerged as future stars. There are “few better ball players on the Browns team,” noted beat reporter W.J. O’Connor.12

It was a busy offseason for the Browns. After the 1915 season, the Federal League, the third major league, which had vied with the National and American Leagues in two litigious seasons, folded. Owners of the eight Federal League teams were permitted to purchase existing, yet financially struggling teams. Charles Weeghman, owner of the Chicago Whales, purchased the Cubs; and Phil Ball, owner of the St. Louis Terriers, acquired the Browns from Robert Lee Hedges. Like Weeghman, Ball combined the rosters of two teams.

Overnight, the moribund franchise was infused with star pitching, including Dave Davenport, who had won 22 games and logged a Federal League best 393⅔ innings in 1915; graybeard Eddie Plank, who at 39 years of age posted 21 wins; and workhorse Bob Groom, who had logged almost 500 innings for the Terriers in two seasons. The task of forming the new team went to Fielder Jones, the former Terriers player-skipper, who replaced Rickey on the field. Rickey was relegated to the role of business manager, but soon clashed with Ball.

At the Browns spring training in Palestine, Texas, Jones whipped 17 Browns and 12 former Terriers players into shape for a 22-player roster. Sportswriter W.J. O’Connor described Koob as “the most promising young southpaw in the American League”; however, Koob’s role on the staff was not clear.13 Another Gateway City scribe, S.M. Halen lauded Koob’s “wagon load of steam” and gushed about his “fadeaway [screwball] and a ‘funeral ball’ that fools them all and he uses all this stuff in an offhand, unconscious manner that irritates the batter.”14

After a productive exhibition season, Koob seemed to have a spot in the rotation wrapped up. But he came down with a severe case of typhoid fever, nearly ruining his season. He was hospitalized, developed pleurisy, a serious inflammation of tissue surrounding the lungs, and missed the first six weeks. He was eased back onto the staff in June, mainly relieving, and made just three starts, while the preseason excitement about the Browns’ possible pennant-challenging season dissolved.

Then Koob found his groove, beginning with a masterful four-hitter in the morning contest of an Independence Day twin bill to defeat the White Sox, 2-1, at Comiskey Park. Ten days later, he went the distance, holding the Red Sox scoreless for 17 innings, yet emerged with a no-decision at Fenway Park when the game was declared a tie. His baserunning blunder in the 15th cost him the victory. Parked on second base, Koob raced home on Ward Miller’s hit and bowled over pitcher Carl Mays at home [who was injured and left the game] and was declared safe by home-plate umpire Brick Owens. The ump reversed his call when Red Sox players pointed out that Koob had failed to touch third.15 Perhaps Koob’s gaffe was not that all expected as he had little experience on the basepaths. A notoriously poor hitter, Koob went 0-for-41 in 1916; however, he did draw 15 walks and scored four times.

Koob was hitting his stride just as the Browns were embarking on one of the best stretches in franchise history. On July 30, he tossed a five-hitter to defeat the Yankees in Sportsman’s Park, then tossed a 10-inning complete game to subdue the Red Sox, 3-2, to record the Browns’ 13th straight victory and improve the team’s slate to 50-49 on August 3. Eddie Plank had taken the youngster under his wing during spring training and his tutoring seemed to have tangible effects. “[Koob] has a cross-fire and a curve that snaps sharper than any I have ever seen,” said Gettysburg Eddie, who compiled a 16-15 slate at age 40. But he acknowledged that Koob still suffered from lapses in control.

After losing a 1-0 heartbreaker to the eventual World Series champions three days later in the same series, Koob blanked the vising Washington Senators on five hits on August 10. It was the Brownies’ 20th win in their last 22 games; they’d win their next three, but cooled off thereafter to conclude the season in fifth place (79-75). After emerging victorious over fellow southpaw Babe Ruth in a 2-1 pitchers’ duel at Fenway Park on the last day of August to push his record to 9-3, Koob, too, cooled off in September, finishing with an 11-8 record. For the season he completed 10 of 20 starts among his 33 appearances, and posted a 2.54 ERA in 166⅔ innings.

The Browns’ success in 1916 raised expectations in 1917, but many wondered if and when that campaign would take place. Tensions ran high between players and owners since the collapse of the Federal League, which had helped drive up player salaries. Owners, sensing a chance to lower their costs, began a policy of entrenchment, leading to general discord. A nascent players union, the Fraternity of Baseball Players, led by Dave Fultz, threatened a strike and claimed to have 1,200 players in their ranks. The National Commission stared down the union and players gradually began breaking from the ranks in mid-January.16 “I don’t care who knows that I have signed,” said Koob, surely recognizing that he had little leverage against the owners. “I have no sympathy with the proposed strike.”17 Several days later, on February 14, Fultz called off the strike. Yet another challenge loomed. On April 6, the US Congress declared war on Germany. Baseball became a showcase for the military, and players were drilled by soldiers in pregame festivities to encourage patriotism.

Koob was “expected to prove the most dependable prop to Fielder Jones’ pitching staff,” pronounced beat reporter W.J. O’Connor, but Koob’s season unfolded differently.18 Both his starts in April were subpar and he concluded the month with a disastrous five-out relief outing, yielding four runs but escaping with the victory. On May 5, Koob was involved in a controversial game, the first no-hitter thrown by a Browns pitcher in Sportsman’s Park. The next day the Chicago Tribune ran the headline, “Koob Tames Sox in One Hit Game, 1-0.”19 How did the Tribune, and other papers across the country using wire services for their sports reports get it wrong? Koob’s no-hitter, opined O’Connor in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, was “hardly immaculate,” and added, “[I]t was slightly tainted, stained with doubt in its very incipiency.”20

After Koob fanned leadoff hitter Shano Collins to start the game, Buck Weaver hit a sharp grounder to second baseman Ernie Johnson, who “fielded [the ball] with his chest, and knocked it silly at his feet,” according to O’Connor. “He then laid a prehensile paw on the pill and came up with ample time” to throw to first baseman George Sisler. “But he suddenly lost his prehensileness and threw the ball over his shoulder like a superstitious person throwing salt to avoid a fight.”21 O’Connor noted that the play instantly evoked a debate in the press box about whether Weaver deserved a hit or Johnson an error. After the game, the official scorer, John B. Sheridan, a St. Louis sportswriter, changed his ruling, which caused a scandal and led to a formal protest by the Base Ball Writers Association of America.

Lost in the commotion was Koob’s commanding victory, though he walked five, in just 94 minutes. Koob’s teammate Bob Groom also held the White Sox hitless in the second game of a twin bill the next day, marking the first and only time (as of 2018) in baseball history that a team held the same opponent hitless on consecutive days.

Five weeks later, the St. Louis Star and Times considered Koob one of the biggest disappointments of the club,” as the 24-year-old lefty failed to live up to preseason hype.22 The Browns drifted back to the far end of the AL standings, finishing in seventh place (57-97), while Koob’s highlights were few and far between. He completed only two starts after his tainted no-no; both were stellar five-hitters. His record dropped to 6-14 while his ERA skyrocketed to 3.91 (the league’s third highest for pitchers with at least 100 innings); he appeared in a career-best 39 games, including 18 starts.

Koob put baseball on hold in 1918 when he enlisted in the Aviation section of the Army. By the end of January he was stationed at newly established Selfridge Field, in Mount Clemens, located north of Detroit on Lake St. Claire, and served with the 380th Aero Squadron.23 Contemporary newspapers reported that it was unclear if Koob eventually learned to fly a plane; it is clear that he pitched for base teams in the United States and as far away as London.24 According to the St. Louis Star and Times, Koob was one of 12 Browns players serving Uncle Sam in 1918.25

Koob was back with the Browns at their spring-training site in San Antonio in 1919. Coming off a fifth-place finish in an abbreviated season (58-64), the Browns looked to Koob to fill an obvious void as southpaws started just seven times the previous season. Dubbed the “Kalamazoo Kithogue” [kithogue is Irish slang for a left-hander] by the Star and Times, Koob had his benders snapping, but was also plagued by a strained back, reported to be a product of his military service.26 After a long layoff against big-league hitters and a lackluster campaign before that, the 26-year-old Koob could not rekindle the magic from his first two seasons with the Brownies. Used primarily in mop-up situations, Koob (2-4) made just four starts among his 24 appearances and posted a dismal 4.64 ERA in 66 innings.

Koob picked up another win in the offseason when he married St. Louis local Florence K. Daly. Together they had one child, Mary Jane, born in 1922.

Koob received a belated and rude wedding present the first week on January 1920 when he was shipped along with right-handed hurler Rasty Wright to the Louisville Colonels of the Double-A American Association in exchange for right-hander Dixie Davis.27 While Davis went on to compile a robust 75-71 slate in parts of seven seasons, Koob never made it back to the big show. He compiled a 23-31 record, completed 19 of 55 starts among his 125 appearances, and carved out a 3.13 ERA in 500 innings.

Koob spent the next 11 seasons chasing his dream. The first nine of those campaigns were spent on the Ohio River in northern Kentucky, where Koob was a sturdy workhorse for the Colonels and manager Joe McCarthy, who later became one of the most successful big-league skippers with the Chicago Cubs, New York Yankees, and Boston Red Sox. He was with the Colonels for just about a month when he tossed a no-hitter on May 11 against the Kansas City Blues, walking five, hitting a batter, and whiffing two.28 After posting a 17-17 slate and logging 251 innings in his first season in the American Association facing primarily players who had or would have big-league experience, Koob enjoyed his best year in professional baseball, winning 22 and hurling 270 innings (ranking fourth in the league in both categories), despite a high 5.07 ERA, helping the Colonels to the league championship. In 1925 the Colonels (106-61) won the league title again, led by three 20-game winners (Nick Cullop, Joe DeBerry, and Ed Holley) while 32-year-old Koob chipped in with a 9-9 slate and 153 innings (6.00 ERA). A dependable workhorse, he posted a 112-113 record and logged 1,904 innings in his nine years with the Colonels. He spent his last two seasons (1930-31) in three different Class A leagues.

Koob lived in Michigan in the St. Joseph’s area during his playing days, but settled in St. Louis with his wife and child when he retired from baseball. They lived in University City, an inner-ring suburb, located about seven miles west of Sportsman’s Park. He was employed by Andrews Manufacturing.

Ernie Koob died at the age of 49 on November 12, 1941, at the Mt. St. Rose Sanitarium in suburban Lemay after a hospitalization of approximately one month. According to his death certificate, the cause was advanced pulmonary tuberculosis. He was buried at Calvary Cemetery in St. Louis, and was joined by his wife in 1964.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Len Levin and fact-checked by David Kritzler.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author accessed Koob’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, extensive use of the archives on the St. Louis Post-Dispatch and St. Louis Star and Times, and SABR.org.

The author also expresses thanks to Bill Mortell for vital assistance research into the player’s genealogy and military record.

Notes

1 “Local Happenings,” Herald-Palladium (St. Joseph, Michigan), March 1, 1913: 5.

2 “Directors Accept Offer of Ernest Koob,” St. Joseph (Michigan) Daily Press, March 11, 1913: 1.

3 “We Lost the Opener but It Took a Real Team to Turn Trick,” St. Joseph (Michigan) Daily Press, May 26, 1913: 1.

4 “Ernie Koob Whiffs 19 in College Game,” St. Joseph (Michigan) Daily Press, April 22, 1915: 1.

5 “Koob Hurls Great Game,” St. Joseph (Michigan) Daily Press, April 29, 1915: 1.

6 “Koob, Sensational College Southpaw, Joins Manager Rickey in Boston,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 17, 1915: 19.

7 “South Michigan League May Turn Against ‘O.B.,’” Indianapolis Star, July 9, 1915: 11.

8 “Weilman Again Tames Detroit; Ham Also Shows,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 23, 1915: 9.

9 “Lowdermilk Gets Chance Today at Speeding Red Sox,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 18, 1915: 17.

10 Billy Murphy, “Have Browns Tom Ramsey’s Successor in Ernie Koob, Young Michigan Collegian?” St. Louis Star and Times, August 31, 1915: 10.

11 Ibid.

12 W.J. O’Connor, “Rickey May Be President of Browns, in Latest Freak of St. Louis Peace Judgment,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 20, 1915: 14.

13 W.J. O’Connor, “Ernie Koob Sick in Bed; Typhoid Attack Is Feared,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 26, 1916: 15.

14 S.M. Halen, “Ernie Koob Is a Game Hurler in Tight Pitches,” St. Louis Star and Times, March 16, 1916: 11.

15 “Browns and Sox Set 1916 Mark for Scoreless Battle,” St. Louis Star and Times, July 15, 1916: 7.

16 Bill Nowlin, “The 1917 Season,” The National Pastime Museum, September 5, 2017, https://thenationalpastimemuseum.com/article/1917-season.

17 W.J. O’Connor, “Ernie Koob Signed; Brown Ball Team Now Strike Proof,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 11, 1917: 29.

18 Ibid.

19 I.E. Sanborn, “Koob Tames Sox in One Hit Game, 1-0,” Chicago Tribune, May 6, 1917: 1.

20 W.J. O’Connor, “No-Hit Game Nets Koob and Browns One-Run Victory,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 6, 1917: 1S.

21 Ibid.

22 “Ernie Koob Case Source of Worry to Manager Jones,” St. Louis Star and Times, June 12, 1917: 8.

23 “‘Lord’ Byron’s First Visit Features Cardinals Defeat,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, April 23, 1918: 22.

24 Dorothy Seymour Mills and Harold Seymour, Baseball: The People’s Game (London: Oxford University Press, 1991), 344.

25 “Sixteen Cardinal Players Now in Service of U.S.,” St. Louis Star and Times, November 7, 1918: 13.

26 “Ernie Koob Works on Hill And Shows Puzzling Benders,” St. Louis Star and Times, March 21, 1919: 17.

27 “Browns Trade Pair of Hurlers for Dixie Davis,” The Dispatch (Moline, Illinois), January 7, 1920: 8.

28 “Southpaw in Fine Fettle,” Courier-Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), May 12, 1920: 6.

Full Name

Ernest Gerald Koob

Born

September 11, 1892 at Keeler, MI (USA)

Died

November 12, 1941 at Lemay, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.