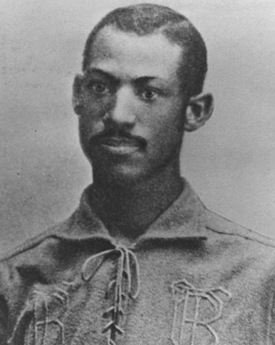

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Moses Fleetwood “Fleet” Walker, an African-American, made his major-league debut with Toledo on May 1, 1884, in an American Association game. The contest was staged in Louisville, and not all Kentuckians and game participants appreciated having a black man playing with and against white men. Many let him know that he was not welcome to do so. Walker, however, stayed the course and played in 42 games for the Toledos before being released late in the season because of injury. He never again played in the major leagues but continued for five more seasons in nearly all-white high minor leagues. He never played for an all-black team. The former law student’s life after professional baseball included his being a husband, a father, an entrepreneur, both a success and failure in business, an author, an inventor, an activist, a felon, a federal prisoner, and a killer of a man. His biographer, David W. Zang, said of him, “Moses Fleetwood Walker was no ordinary man, and in the 1880s he was no ordinary baseball player.”1

Moses Fleetwood “Fleet” Walker, an African-American, made his major-league debut with Toledo on May 1, 1884, in an American Association game. The contest was staged in Louisville, and not all Kentuckians and game participants appreciated having a black man playing with and against white men. Many let him know that he was not welcome to do so. Walker, however, stayed the course and played in 42 games for the Toledos before being released late in the season because of injury. He never again played in the major leagues but continued for five more seasons in nearly all-white high minor leagues. He never played for an all-black team. The former law student’s life after professional baseball included his being a husband, a father, an entrepreneur, both a success and failure in business, an author, an inventor, an activist, a felon, a federal prisoner, and a killer of a man. His biographer, David W. Zang, said of him, “Moses Fleetwood Walker was no ordinary man, and in the 1880s he was no ordinary baseball player.”1

Moses Fleetwood Walker was born in the eastern Ohio community of Mount Pleasant, Jefferson County, on October 7, 1856. He was the third son of the six or seven children born to Moses W. Walker and Caroline O’Harra Walker, both of whom were of mixed race. His younger brother, Weldy, also was a baseball player and was the second black man to appear in a major-league game. The early history of both parents is unclear but by 1870 the family had moved to Steubenville, also in Jefferson County, where Moses W. Walker worked as a cooper. He later became one of the first black physicians in Ohio and a minister of the Methodist Episcopal Church.

Known as Fleet by early adulthood, young Moses most probably began his relationship with baseball as a youth in Steubenville. But the first record of his play came following his father’s 1877 call to serve the Second Methodist Episcopal Church in Oberlin, Ohio. Twenty-year-old Fleet Walker enrolled in the preparatory program at Oberlin College that same year. He soon established himself as the catcher and leadoff hitter on the Oberlin College prep team. In the fall of 1878 he enrolled in the classical and scientific course in the department of philosophy and arts, Class of 1882. He continued to be attracted to and to play baseball. He was initially an excellent student, but his grades suffered significantly as his proficiency at the game increased. Contributing to his decline in academic interest may have been the loss of family discipline due to the departure of his father to another church post in 1878. Another contributing factor was, no doubt, romance. Walker met his future wives, both Oberlin students, during this time.

Baseball at Oberlin was limited to interclass play when the college dedicated a new baseball field in 1880. During that inaugural contest, Walker caught and struck a memorable grand slam. He and his batterymate, Harlan Burket, led the junior class to a win over the senior nine. Then in 1881, Oberlin College fielded its first varsity intercollegiate team. Members included Fleet, his younger brother Weldy Wilberforce Walker and Burket – all future professional players. The season’s final game was a 9-2 win over the University of Michigan. Burket reported that Walker and teammate Arthur Packer so impressed the Michiganders that they were invited to transfer there. They did, in fact, with Weldy joining them in the move. Also accompanying Fleet was 18-year-old Arabella “Bella” Taylor, who would become his first wife.

But first, there was an important game in which Fleet played a key role though he did not play in it. He was paid by the White Sewing Machine Company of Cleveland to catch for its semipro team during the summer of 1881. The club journeyed to Louisville, Kentucky, for an August 21 game against the Eclipse nine. The locals were a crack club that would enter the American Association as a charter member the following year. Seven members of the Eclipse club played in the major leagues in 1882, five with Louisville. The Eclipse players initiated Walker into the hard realities of prejudice and bigotry that would become integral to the game, in part because of Fleet Walker’s own actions. The Louisville Courier-Journal reported the following day that “players of the Eclipse Club objected to Walker playing on account of his color.”2 The Clevelands responded by holding Walker out of the starting lineup. Already greatly weakened by the loss of their starting catcher, the visitors suffered a double whammy when Walker’s replacement injured his hand in the first inning and refused to come out for the second. At this juncture and with the apparent support of the spectators, Fleet took to the field and prepared to enter the game. The local newspaper went onto say that during his warm-up, “He made several brilliant throws and fine catches while the game waited.”3 But some Eclipse players still objected to Walker’s playing and two, Johnnie Reccius and Fritz Pfeffer, left the field and went to the clubhouse in protest. In the end, “The objection of the Eclipse players, however, was too much and Walker was compelled to retire. …”4 Finally, the Cleveland third baseman volunteered to go behind the plate and Louisville went on to beat the Whites, 6-3.

Fleet enrolled at the University of Michigan for his third year of college-level study in the spring of 1882. It was baseball that had taken him there, but other purposes were served as well. The transfer enabled him to pursue the study of law and to avoid any stigma of Bella’s soon-to-be-apparent pregnancy in Oberlin.

Hopes were high for a successful spring 1882 baseball season at the University of Michigan as Fleet Walker greatly strengthened the team’s weakest position. The team practiced in the gymnasium daily during the winter and raised money for new uniforms and care of their grounds. The Ann Arbor squad made good on the promise by winning 10 of 13 games. Fleet was a leading hitter, both for average and power, but earned the greatest accolades for his catching. The college paper referred to him as “the wonder.”5

In July Fleet married Bella Taylor in Hudson, Michigan, but left her soon after to play baseball in New Castle, Pennsylvania. There, for the first time, he played an extended period of professional baseball that was covered extensively by the local press. His 1882 late-summer exploits at New Castle launched his reputation in baseball circles as a top-notch catcher.

New Castle, about 50 miles north of Pittsburgh, welcomed Walker as a member of the Neshannocks. The team, known as the Nocks, was billed as an amateur outfit but Walker and some others were paid. Already on the Nocks roster was Walker’s mate and pitcher at Oberlin, Harlan Burket. The local press gave advance notice of Walker’s impending arrival with glowing reviews calling him “…one of the best catchers in the country” and “a gentleman in every sense of the word both on the ball field and off.”6 According to Zang, the New Castle papers, unlike those in every other city where Walker played professionally, never made reference to Fleet Walker’s color. Walker “was brilliant behind the bat”7 for the Nocks and left for Ann Arbor to resume his law studies in September.

The following spring, 1883, Walker did not play at Michigan or at New Castle. Instead, he left school and answered the call to become a professional baseball player. William Voltz, manager of the Toledo entry in the Northwestern League, signed Walker as a catcher for the city’s first professional team. However, an effort was made to end Walker’s career in Organized Baseball before it started. Among the business conducted by the Executive Committee of the Northwestern League during a meeting at Toledo’s Boody House Hotel on March 14, 1883 was the following:

A motion was made by a representative from Peoria that no colored player be allowed in the league. This created quite a discussion. It is well known that the catcher of the Toledo club is a colored man. Besides being a good player he is intelligent and has many friends. The motion which would have expelled him was fought bitterly and finally laid on the table.8

Catching in the 1880s was a brutal proposition. Generally, the only protective equipment employed by Walker was a mask. According to a Toledo batboy’s much later recollection, he “occasionally wore ordinary lambskin gloves with the fingers slit and slightly padded in the palm; more often he caught barehanded.”9 Nonetheless, Walker proved durable and played in 60 of Toledo’s 84 championship games and appeared in a majority of pre- and postseason exhibitions as well. He hit a then-decent .251 but it was on defense that he shone and made his most significant contributions to Toledo’s pennant-winning season. The Toledo Blade said of him, “Walker has played more games and has been of greater value behind the bat than any catcher in the league.”10 Sporting Life chimed in with “Toledo’s colored catcher is looming up as a great man behind the bat.”11 It also said that he and Hank O’Day formed one of the most remarkable batteries in the country.”12 Most often the press used an adjective referring to Walker’s color when describing him or his play.

The beginning of the end of African-American participation in Organized Baseball may have begun when Cap Anson brought his Chicago White Stockings team to Toledo for an in-season exhibition game on August 10, 1883. Anson was the team’s very capable leader, a Hall of Fame-bound player and an outspoken racial bigot. His views were hardly unique at the time, within baseball or the country at large, but his prominent position made him a major factor in segregating baseball. The Toledo Daily Blade’s lengthy account is not at all complimentary of either Anson or his team. Further, it is exceedingly supportive of Walker and indicates that the Toledo management came to his defense and suggests that the city did as well.

“Walker, the colored catcher of the Toledo Club … was a source of contention between the home club and … the Chicago Club. Shortly after their arrival in the city … the Toledo Club was … informed that there was objection in the Chicago Club to Toledo’s playing Walker, the colored catcher.

“Walker has a very sore hand, and it had not been intended to play him in yesterday’s game, and this was stated to the bearer of the announcement for the Chicagos. … Not content with this, the visitors … declared with the swagger for which they are noted, that they would play ball ‘with no d—-d nigger.’ … [T]he order was given, then and there, to play Walker and the beefy bluffer was informed that he could play or go, just as he blank pleased. Anson hauled in his horns somewhat and ‘consented’ to play, remarking, ‘We’ll play this here game, but won’t play never no more with the nigger in.’ ”13

Toledo’s manager, Charlie Morton, who had replaced Voltz early in the season, called Anson’s bluff, forcing the latter to the field to secure his interest in the day’s gate receipts.

But Anson’s bold statement, “won’t play never no more with the nigger in,”14 proved to be the case, as he never did play against Walker. The incident of August 10, 1883, in Toledo certainly brought the issue to the forefront and began an open, blatant, and successful effort to bar black players from Organized Baseball.

Toledo’s success of 1883 propelled the city’s team into the American Association for the following season. Fleet went right along but neither he nor the Toledos fared as well in the faster company of a major league as they had the previous season. The team finished eighth in the ten-team circuit with Walker appearing in just 42 of the 104 games played. Walker’s 1884 season was no more of a success than his team’s.

Walker’s major-league debut, a baseball milestone game, saw him return to Louisville, where because of his race he had been forbidden to play three summers before. Again, tension was high and may well have contributed to Walker’s poor defensive performance and a loss. Walker was constantly subjected to abuse from fans, the press, players who did not want to take the field against him, and even his teammates. From the latter group, Walker may have had the worst experience from at least two fellow players who were open segregationists. One was outfielder Curt Welch, who played both the 1883 and 1884 seasons as Walker’s teammate; the other was Toledo’s workhorse pitcher in 1884, Tony Mullane. Walker worked under an unbelievable handicap with his batterymate that was held in secret by the pair until revealed by Mullane decades later when the New York Age of January 11, 1919, reported: “Toledo once had a colored man who was declared by many to be the greatest catcher of the time and greater even than his contemporary, Buck Ewing. Tony Mullane … than whom no pitcher ever had more speed, was pitching for Toledo and he did not like to be the battery partner of a Negro. “He [Walker] was the best catcher I ever worked with, but I disliked a Negro and whenever I had to pitch to him I used to pitch anything I wanted without looking at his signals. One day he signaled me for a curve and I shot a fast ball at him. He caught it and came down to me. … He said, ‘I’ll catch you without signals, but I won’t catch you if you are going to cross me when I give you signals.’ And all the rest of that season he caught me and caught anything I pitched without knowing what was coming.”15

Racial pressure against both Walker and the club was constant. Prior to the Toledos’ visit to the Southern city of Richmond, Virginia, Toledo manager Charlie Morton received this letter written September 5, 1884:

“Manager Toledo Base Ball Club:

Dear Sir: We the undersigned, do hereby warn you not to put up Walker, the Negro catcher, the evenings that you play in Richmond, as we could mention the names of 75 determined men who have sworn to mob Walker if he comes to the ground in a suit. We hope you will listen to our words of warning, so that there will be no trouble: but if you do not, there certainly will be. We only write this to prevent much blood shed, as you alone can prevent.”16

The Toledo club released Walker due to an injury three weeks before the trip to Richmond, and the threat became moot.

Some modern researchers have found hatred motives in an 1884 team photograph where they do not exist. The oft-published image does not include Fleet Walker or his brother Weldy, who was with the team for five games in midseason. There is good reason for their absence: Both had been released before the picture was taken.

For his shortened season, Fleet batted .263, third best on the team and 23 points above the league average, but he was plagued by injuries. He played in just six games after July 12 and was finally released on September 22. He never returned to the major leagues.

Bella and Fleet had made their home in Toledo and continued to do so after his release. Their second child, Thomas, was born there in August. Young Thomas joined his sister, Cleodolinda, who had been born in December of 1882. Their third and last child, George, came in another two years. Late in the year Fleet took a job as a postal clerk in Toledo but by spring was back in baseball. He signed with Cleveland of the Western League for the 1885 season, but his time there was short-lived. He played in just 18 games before his club folded as did the Western League just days later, on June 15. Fleet then latched on with the minor-league team in Waterbury, Connecticut, which played successively in three different leagues that year; he appeared in 39 games.

After the 1885 season, Fleet returned to Cleveland and assumed the proprietorship of the LeGrande House, a hotel-theater-opera house. He was reunited with and assisted by his brother Weldy. That Fleet was able to finance such a venture may be a testament to his earning power as a baseball player. According to Zang’s research and citation of Sporting Life, Walker may have earned as much as $2,000 for a summer’s work while a major leaguer at a time when a laborer earned about $10 a week.17 He was no longer able to demand a salary in that range, but his skills were still sought after, and he was engaged to return to Waterbury for an entire season in the Eastern League.

Walker played in about half of Waterbury’s games in 1886 and compiled lackluster statistics. In spite of that mediocre performance, he landed a job with defending champion Newark of the highly regarded International Association for 1887. Here he formed an effective all-black battery with George Stovey. Stovey won 33 games while Walker, in spite of injuries, established career bests in games played, batting average, and fielding percentage. On July 14 Cap Anson made good on the promise he made in Toledo in 1883 not to share the field with black players when he and his Chicago White Stockings came to Newark for an exhibition game. On Anson’s demand, neither Walker nor Stovey played. Cap Anson was not entirely responsible for baseball’s more than a half-century of segregation but he and Fleet Walker had a lot to do with forcing it. That same day, the International League acted not to approve the contracts of additional black players.

Walker followed his former Newark manager to Syracuse, also of the International Association, for 1888. At the age of 31 he was the Stars’ front-line catcher and, in spite of anemic hitting, helped them to the pennant. He returned to Syracuse for the 1889 season but slumped defensively and continued to be weak at the bat. A precursor of coming financial and legal issues occurred on a June trip to Toledo when the Stars’ gate receipts were attached to satisfy debts that Walker had left there. His baseball career ended when he was released on August 23 and became the last black man to play in the International League until Jackie Robinson joined Montreal in 1946.

Fleet Walker remained in Syracuse and again joined the postal service as a railway clerk. Then, on April 9, 1891, he became a killer when he fatally stabbed one of a small group of white men on the streets of Syracuse during an exchange of racial insults. All the participants had been drinking. Walker was found not guilty of second-degree murder by a jury of 12 white men. Later in 1891 he returned to his roots in Steubenville. He again was an employee of the post office and involved himself with the Knights of Pythias and later the Negro Masons. His wife, Arabella, died of cancer in 1895, and he married an Oberlin classmate, Ednah Mason, in 1898. Then in September 1898 Walker was arrested, convicted, and sentenced for mail robbery. He ended a tumultuous decade, during which both his parents had died, with a year as a federal prisoner.

After his release Walker he returned with Ednah and the three children to Steubenville, where he and his brother Weldy operated the Union Hotel. In 1904 Fleet became the manager of the Opera House in nearby Cadiz, Ohio. During this time, he and Weldy jointly edited a black-issues newspaper, The Equator, which explored the idea of black Americans emigrating to Africa. That idea morphed into a 1908 book, Our Home Colony, which Zang called “certainly the most learned book a professional athlete ever wrote.”18

The Opera House played opera, live acts of many kinds, and motion pictures and was operated by Fleet and Ednah. Walker earned a reputation as a “knowledgeable and respected businessman.”19 While there he patented three inventions for improving the changing of movie reels. Coupled with an earlier patent for an exploding artillery shell, he was a bona-fide inventor. After 22 years of marriage, Ednah died in 1920. Walker then sold the Opera House and eventually landed in Cleveland, again with Weldy, and operated the Temple Theater for a few months.

On May 11, 1924, Moses Fleetwood Walker died at his Cleveland home of lobar pneumonia. He was preceded in death by two wives, the first of whom delivered him two sons and a daughter. His only grandchild did not survive infancy, and so he left no direct descendants. He was buried, in a grave unmarked until 1991, at Union Cemetery in Steubenville, Ohio.

Setting the Record Straight

Sunday, April 15, 2007, was observed as Jackie Robinson Day across America as individual players and all of Robinson’s Dodgers honored Robinson by wearing his retired number 42. The date marked the 60th anniversary of Robinson’s major-league debut, an event referred to by many as “breaking the color barrier.” Robinson’s career in major-league baseball was stellar and significant as it began baseball’s 20th-century integration. But Robinson was not the first black man to play major-league baseball. That honor belongs to Moses Fleetwood Walker.

Moses Fleetwood Walker of the 1884 Toledo team is, without question, the first to play major league baseball openly as a black man. His brother Weldy became the second to do so that same year, also in Toledo. Jackie Robinson, the best known of these black players became the third, much later. There is no quarrel that Toledo was a major-league city that year or that the Walkers were team members. Baseball historians, researchers, writers, the Mud Hens, yours truly, and John Thorn, major-league baseball’s official historian, all agree. Thorn has said of Walker, “He would be the last black player in the major leagues until 1947.”

Recent research has caused some, including Thorn, to suggest that still another man was the first black to play major-league baseball. William Edward White, who was partly African-American and partly white, did have a one-game major-league career in 1879. White, however, played and lived his life as a white man and faced none of the trials that Walker and Robinson did. Despite the retroactive application of genetic rules, I believe that if Mr. White said he was white, we should consider him white.

Why then does the myth persist that Jackie Robinson was first? Could it be because Walker played so long ago that what he did no longer seems relevant? Or could it be because the league in which he played has not survived? Could it be that Robinson played within the memory of still living Americans and so is favored by them? I believe the answer is that Walker’s action resulted in the segregation of major-league baseball. Robinson’s, on the other hand, resulted in a completely opposite and positive outcome – the integration of the game.

Both Walker and Robinson met and withstood the assault of racial bigotry. Their experiences were often painful and very similar but separated by 63 years. Their times were very different and the results of their actions were very different. But without question, Moses Fleetwood Walker was the first.

Author’s note

The author relied heavily on David Zang’s definitive biography of Moses Fleetwood, Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart. The work is well-researched, well-documented, well-written and complete.

Sources

Chalk, Ocania, Pioneers of Black Sport (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1975).

International League of Professional Baseball Clubs, 2013 International League Record Book (Dublin, Ohio: International League of Professional Baseball Clubs, 2013).

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 2007).

Lin Weber, Ralph Elliott, ed. The Toledo Baseball Guide of the Mud Hens 1883-1943 (Rossford, Ohio: Baseball Research Bureau, 1944).

Madden, W.C., and Patrick J. Stewart. The Western League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2002).

Mancuso, Peter, “The Color Line Is Drawn,” in Bill Felber, ed., Inventing Baseball (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2013).

McBane, Richard, A Fine-Lot of Ball-Tossers: The Remarkable Akrons of 1881 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005).

Thorn, John, Baseball in the Garden of Eden (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

Zang, David W., Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart: The Life of Baseball’s First Black Major Leaguer (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995).

Toledo Evening Bee

Toledo Daily Blade

Lucas County (Ohio) Probate Court Records, Birth Records, July 30, 1884.

Toledo City Directory 1885-1886.

ancestry.com.

baseball-reference.com.

jockbio.com.

Notes

1 David W. Zang, Fleet Walker’s Divided Heart: The Life of Baseball’s First Black Major Leaguer (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 34.

2 John Thorn, Baseball in the Garden of Eden (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011), 185.

3 Thorn, 186.

4 Ibid.

5 Zang, 29.

6 Zang, 30.

7 Zang, 32.

8 Toledo Daily Blade, March 15, 1883, 3.

9 Zang, 37.

10 Zang, 38.

11 Zang, 37.

12 Zang, 39.

13 Toledo Daily Blade, August 11, 1883, 3.

14 Ibid.

15 Ocania Chalk, Pioneers of Black Sport (New York: Dodd, Mead & Company, 1975), 8.

16 Toledo Evening Bee, September 18, 1884, 4.

17 Zang, 37.

18 Zang, 97.

19 Zang, 120.

Full Name

Moses Fleetwood Walker

Born

October 7, 1856 at Mount Pleasant, OH (USA)

Died

May 11, 1924 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.