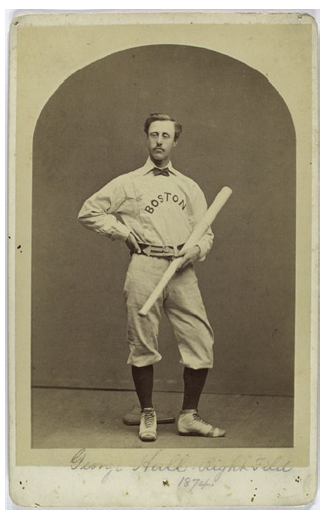

George Hall

Baseball fans generally remember players who are involved in some of game’s most famous events. The same can be assumed of players who are the first to accomplish a particular feat in the game. However, George Hall was both a central figure in one of major-league baseball’s earliest scandals and the first major-league player to earn the title of “home run king,” but is all but forgotten by the average baseball fan. Hall’s career ended abruptly in 1877 and he essentially vanished from the modern historical record. He was one of the better hitters of the era. His batting skill, involvement in some of early baseball’s famous events, and subsequent fall from grace make him one of the more colorful players in the 19th century.

Baseball fans generally remember players who are involved in some of game’s most famous events. The same can be assumed of players who are the first to accomplish a particular feat in the game. However, George Hall was both a central figure in one of major-league baseball’s earliest scandals and the first major-league player to earn the title of “home run king,” but is all but forgotten by the average baseball fan. Hall’s career ended abruptly in 1877 and he essentially vanished from the modern historical record. He was one of the better hitters of the era. His batting skill, involvement in some of early baseball’s famous events, and subsequent fall from grace make him one of the more colorful players in the 19th century.

George William Hall was born on March 29, 1849, 1 in Stepney, England, to George R. and Mary Hall; he was the third of five children. Hall’s father, an engraver, emigrated from England to the United States around the time Mary birthed their fourth child, Edwin. Mary and her four children immigrated to the United States soon thereafter and arrived at New York on July 26, 1854.2 George developed an affinity for baseball in his adolescent years in Brooklyn and proved to be an adequate fielder and skilled with the bat.3

Hall began his baseball career as an amateur and played for the Excelsior Juniors of Brooklyn in 1868 and as a first baseman for the Cambridge Stars (New York) in 1868 and 1869.4 In 1870 he joined the Brooklyn Atlantics and was responsible for ending the most famous undefeated streak in professional sports history. On June 14, 1870, the Cincinnati Red Stockings brought their unblemished 57-0 record to the Capitoline Grounds in Brooklyn to face the Atlantics. Henry Chadwick’s Base-ball Manual for 1871 estimated that nearly 10,000 people watched as the Atlantics and the Red Stockings played an intense match. Cincinnati led 3-0 after three innings, but the Atlantics rallied to score four runs in the following three innings. “The game now began to get quite exciting, and every movement of the players was watched with eagerness.”5 The teams traded the lead and were tied 5-5 after nine innings. Cincinnati refused to accept a tie-game outcome and sought to finish the match. In the 11th, the Atlantics tied the score again. Charles Ferguson was on second and George Zettlein at first. Hall batted next but what unfolded next is unclear.

Hall stepped up to the plate and hit Asa Brainard’s pitch to George Wright, who tossed the ball to Charlie Sweasy. At this point, the reports begin to differ. Cincinnati newspapers agree that Sweasy muffed the ball and hurried a throw to catcher Doug Allison, who did not catch the ball. “Hall hit to Wright, who threw to Sweasy, who muffed and threw to Alison, who missed it, and Ferguson scored the winning run. [Long and tremendous cheering.]”6 The New York Tribune simply states that “Hall closed the game in triumph for the Atlantics; his hit released Ferguson, who ran over the plate, winning the game by one run.”7 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle held that Hall got a hit. “Hall batted Zettlein out at second, and was nearly put out at second himself, but Sweasey dropped the ball passed in by George Wright, and Fergy got home, making the winning run.”8 Most newspapers held that Sweasy dropped the ball and threw the ball errantly to home plate, allowing Ferguson to score but it was Hall’s action that initiated the play that ended Cincinnati’s unbeaten streak. Chadwick’s guide called the game “The Match of the Season of 1870.”9

Despite the incredible victory, the Atlantics reorganized as an amateur club in 1871. Because of this, Hall decided to take his services elsewhere and found a home as a center fielder for the Washington Olympics of the newly christened National Association. Hall batted .294 in 1871 and continued to impress fans and players with his speed. In 1872 the Olympics reorganized as a co-op team and Hall again decided to move on, this time to Baltimore. He spent 1872 and 1873 as a member of the Baltimore Canaries (also known as the Lord Baltimores). Hall batted .340 in his two years with Baltimore and ranked third in the league in doubles and triples in 1872. Baltimore folded in 1874 despite strong second-place finishes in 1872 and 1873. The Panic of 1873 affected Baltimore’s proprietors and the funds for the Canaries quickly vanished.10 Financial uncertainty led Hall to leave Baltimore before the 1874 season and sign with the Boston Red Stockings for half of his 1873 salary.11

George Hall’s experience highlights the volatility and financial unease of 19th century baseball clubs. Prior to the formation of the National League, clubs, and especially their players, were at the mercy of gate receipts in order to stay afloat. An ambitious schedule and the need to travel from city to city made it difficult to remain financially stable and profitable on a consistent basis. Thus, players like Hall found it difficult to make a living playing the game they loved. However, players made important – and at times detrimental – personal connections when they jumped from club to club. Hall is no exception, as he met a shady character named Bill Craver and was likely introduced to his future wife, Ida Layfield, a Maryland native, while a member of the Canaries.12 George and Ida were married in 1876 while George played for the Athletics of Philadelphia.13

In 1874 Hall joined the best baseball club in the National Association, the Boston Red Stockings. The Red Stockings were crowned National Association champions in 1872 and 1873 and fielded a roster that included five future Hall of Famers, George Wright, Harry Wright, Jim O’Rourke, Deacon White, and Al Spalding. Although Hall’s career hitting statistics suggest he was a slightly above-average player, his addition to the best professional squad in the National Association speaks volumes. Both Wright Brothers, Andy Leonard, and especially Cal McVey knew how dangerous Hall could be with the bat. Additionally, McVey was Hall’s teammate in Baltimore in 1873, where the two batted .380 and .345 respectively. It’s possible that Harry Wright signed Hall at McVey’s urging. With Boston Hall split time in the outfield with the aging legend Harry Wright and others. Combined with his offensive skill, Hall’s defensive prowess improved the Boston outfield. The New York Clipper commented, “Hall was the crack player south of Philadelphia at centre field.”14 Hall’s versatile defensive talents blended nicely with the evolving understanding of outfield play. Prior to 1874, the right fielder was considered the weakest of the three, with the best outfielder playing in left field. By 1874 the Clipper opined that right field was the most active due to the lack of a shortstop on that side, but all outfield positions essentially required equal skill.15 “As a general thing, however, the three positions required the same qualities, viz., long-distance throwing, sure catching, and good judgment in the guaging [sic] of balls.”16 Pitching improved in several ways so fewer balls were hit to the outfield. Thus, by 1874, outfielders were standing much closer to the infield than in the game’s early days. Hall’s speed helped him in this style of play because he could quickly track a ball down if one were hit well, deep into the outfield. His arm was likely good to above average because he played all outfield positions successfully.17 Outfielders like Hall had to be incredibly athletic to succeed. “It will not do, therefore, to put any but the best men in those positions,” the Clipper opined.18

The Red Stockings’ first National Association game of 1874 was against the New York Mutuals on May 2. Hall’s first professional contest played with Boston was a significant one as he replaced Harry Wright in the lineup, “filling (Wright’s) position acceptably at centre-field.”19 He had one hit, scored a run, and made two putouts in center field. But Hall’s season was mediocre– actually the worst of his professional career. This is possibly due to his limited playing time; Hall played in only 47 of the 71 scheduled league games. His role on the club was again as a rotating outfielder, splitting most of his time with Harry Wright. Hall batted .288 and had 64 hits, one home run, and 34 RBIs, all figures either career lows or close to them. Still, Hall played a role in one of baseball history’s grandest tours: the 1874 World Base Ball Tour.

The Clipper called the tour “The Grand International Tour.”20 In the winter of 1873 Harry Wright proposed that the Red Stockings and Athletic of Philadelphia sail across the Atlantic in the summer of 1874 and expose Europeans to the American game. Hall returned to his country of birth on July 27, 1874, and played his first game on July 30 at the Liverpool Cricket Grounds in front of 500 onlookers. He scored two runs in the 14-11 loss to Athletic. On July 31 Hall hit one of Boston’s five home runs as the Red Stockings beat the Athletic, 23-18. This trend continued for the entire tour as he proved to be an offensive force. He hit in every game but one and belted at least two home runs.21 The London Times noted that Hall was a good fielder.22 He established himself as one of the best players on the tour. The teams returned to America on September 9. The tour proved to be a financial failure; the English reacted indifferently to the American game. “Some American athletes are trying to introduce us to their game of base-ball, as if it were a novelty; whereas the fact is that it is an ancient English game, long ago discarded in favour of cricket,” the Times lectured.23 The Red Stockings completed their season on October 30 with a loss to Hartford. Boston finished 1874 atop the National Association standings with a 52-18-1 record.

Despite playing for a champion, Hall signed with the Athletic of Philadelphia for the 1875 season. The reasons are unknown but Philadelphia may have offered a higher salary to Hall, who hit extremely well against the Athletic in Europe. In his first season with Philadelphia, Hall hit .299, with 107 hits, 4 home runs, and 62 RBIs. His play was above average (2.3 WAR) but Philadelphia finished a distant third to Boston in the final standings. The Red Stockings were a major catalyst in the National Association’s collapse in 1875 – they were simply too good and attendance waned. Chicago businessman William Hulbert formed the National League officially in February 1876. He viewed the National Association as corrupt, mismanaged, and, worst of all, weak. Hall decided to stick with Philadelphia for 1876, a decision that set up his best season in professional baseball.

The National Association’s best clubs from 1875 squared off against one another on April 22, 1876, in Philadelphia.24 Hall had several clutch at-bats that kept Philadelphia in the game. Regardless, the Athletics dropped the opener to the Red Caps, 6-5. Once again Hall was at the center of baseball history as he played a crucial role in the National League’s origin story. Although the game is now a famous first, Hall’s play in a forgotten game later that season was arguably his best performance.

The Cincinnati Reds arrived in Philadelphia and began a three-game series against the Athletics on June 14. (The first game was scheduled for June 13 but was rained out.) Both teams were bad; the Athletic carried a 5-15 record into the set while the Reds sported a balmy 4-17 record; no wonder that “the attendance was small.”25 Despite their poor record, Philadelphia put on a powerful offensive display. “The extraordinary batting of the Athletics on this occasion has perhaps never been equaled, and certainly, has not been excelled. … Hall’s wonderful batting was the feature. …”26 During the game, Hall tallied five hits in six plate appearances, “once making a clean home-run by driving the ball over the right-field fence, and making, besides, three three-basers [triples].”27 It is likely that his omitted fifth hit was a single because the Clipper noted all Athletics who registered extra-base hits that day. Thus, George Hall was probably a double away from being the first major-league player to hit for the cycle.28 His home run – one of his league-leading five in 1876 – was rare for two reasons: 1) He hit a home run in the fifth inning and 2) the ball bounded over the fence (a legal home run at the time). Such home runs were rare in the 19th century. That he hit a dead ball deep enough to bound over the fence in the middle of a game in which the Athletics notched 20 runs on 23 hits is even more impressive. The ball was surely a misshapen blob at that point. Three days later Hall hit two home runs off Amos Booth of the Reds, becoming the first player to hit more than one in a game.29 The veteran had his best offensive season in 1876, batting.366 with 98 hits, 5 home runs, and 45 RBIs in 268 at-bats. His league-leading five home runs crowned him professional baseball’s first “home run king.”

Despite Hall’s success, the 1876 Athletics were a bad team, mostly young and inexperienced.30 Financial woes hit the club hard, and it failed to complete its scheduled final Western road trip, no-shows for series in Chicago and St. Louis. The club also owed every player between $200 and $500 in back pay. Rumors circulated in Philadelphia that a new club would be organized, using the players from 1876.”31 Hall told the team management that he would stay,32 but, the Athletics were barred from the National League for the 1877 season, leaving him without a team.

Hall soon found a home along with former teammate Bill Craver on the Louisville Grays. The Grays were a formidable team with pitching ace Jim Devlin on the roster. While Chicago and Hartford failed to translate their 1876 success into the 1877 season, Louisville transformed itself from a mediocre team in 1876 to pennant contenders. On August 13 the Grays had a four-game lead over St. Louis with a 27-13 record. St. Louis offered Hall a contract for 1878. (He also expressed interest in joining the Cincinnati nine for 1878.) For whatever reason, he had no interest in signing again with Louisville, even though his salary was a healthy $2,800.33 Hall was a major catalyst for Louisville’s success in 1877, batting .323, but he was also a major factor in the club’s downfall.

The Grays were leading the pennant race by 3½ games midway through August. Suddenly, with 20 games left in the season, Louisville began to drop games. Between August 17 and September 26, the Grays went 2-11-1 and ended the season on October 6 with a 35-25 record, good enough for second place, but a distant seven games behind. Hall led the team in hitting on August 17 but hit just .143 on the final road trip.34 His performance and that of a few teammates increased suspicion that games were being fixed. John A. Haldeman, a baseball writer for the Louisville Courier-Journal, learned that four players, including Hall, had been persuaded by gamblers to throw games.35 Furthermore, after the ill-fated Eastern road trip, Hall sported a new diamond pin and cluster diamond ring.36

Speculation about the purported Louisville scandal increased at season’s end. Club owner Charles Chase interviewed Jim Devlin, who said he played loosely only during exhibition games. “Hall had seen Devlin enter Chase’s office that morning and was now filled with anxiety that he had blown the whistle on him.”37 Hall offered to tell Chase about the scandal’s mechanics if Chase “promised to let [him] down easy.”38 Eventually Hall admitted to fixing games. On October 26, at a meeting of the Grays’ board of directors with the entire team to discuss the Grays’ last 20 games, Hall maintained that he accepted payment only to throw non-League games.39 Four days later, the directors expelled Hall and others from the Louisville club. Despite that, and the League rule barring players convicted of disreputable play from signing with other National League clubs, St. Louis signed both Devlin and Hall for the 1878 season.40 On December 5 the National League Board unanimously banned Hall, Devlin, Bill Craver, and Albert Nichols from signing with any National League club until reinstated.41

The National League never reinstated Hall, and he eventually faded into obscurity. Rumors spread that he continued to play for nonleague teams, but no evidence of that has been founed. Hall moved back to Brooklyn with his wife, Ida, and took up steel engraving, his father’s trade. The couple had six children. Ida died of acute nephritis in 1912 and was buried in Brooklyn’s Evergreen Cemetery. In his later years, George either quit or retired from the engraving profession and became a clerk in a New York art museum. He died of heart trouble on June 11, 1923, and was buried next to his wife.

Hall was involved in some of professional baseball’s earliest key moments and established himself as one of the era’s better players. Baseball historian and statistician Bill James labeled him baseball’s “Least Admirable Superstar” of the 1870s.42 Hall’s role in baseball’s largest scandal of the 19th century continues to overshadow his skill as a player. He completed his career with a .322 batting average with 13 home runs, 252 RBIs, and 538 hits.

Notes

1 Hall’s birth date is disputed. Most sources claim March 29, 1849, as his date of birth while his death certificate states that it was June 22, 1849.

2 They immigrated to the United States aboard the Sir Robert Peel. Year: 1854; Arrival: New York, New York; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Microfilm Roll: Roll 143; Line: 22; List Number: 928.

3 James D. Smith III, “George William Hall,” from the archives of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum.

4 Ibid.

5 Henry Chadwick, Chadwick’s Base Ball Manual, baseballchronology.com/baseball/Books/Classic/Henry-Chadwicks-Baseball-Manual/Page-2.asp#70RedStockings1stLoss.

6 “Base-Ball: The Atlantics of Brooklyn Beat the Champions by a Score of 8 to 7 in a Game of 11 Innings, the Rest on Record,” Cincinnati Daily Enquirer, June 15, 1870.

7 “Base-Ball: Atlantics vs. Red Stockings,” New York Tribune, June 15, 1870.

8 “The Atlantics Triumphant,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 15, 1870.

9 Chadwick’s Base Ball Manual.

10 Joe Tropea, “Your Baltimore Canaries: A Very Brief History of Baltimore’s Second Professional Base Ball Team,” Maryland Historical Society, April 3, 2013. mdhs.org/underbelly/2013/04/03/your-baltimore-canaries-a-very-brief-history-of-baltimores-second-professional-base-ball-team/.

11 George V. Tuohey, A History of the Boston Base Ball Club (Boston: M.F. Quinn & Company, 1897), 68; Baseball-reference.com cites, per Preston Orem, that Hall’s salary was $1,000 with Baltimore in 1873 and $500 with Boston in 1874. If this is true, then the financial situation must have been truly perilous for Hall to accept half his salary with an employer 400 miles north of Baltimore.

12 Borough of Brooklyn, New York. Death Certificate number illegible (1912), Ida Aurelia Hall; Bureau of Vital Records, New York.

13 The 1900 US Census states that George and Ida were married for 24 years (1876). 1900 U.S. census, Kings County, New York, population schedule, New York City (page 16), dwelling 280, family 340, George W. and Ida A. Hall; digital image, Ancestry.com, Accessed September 25, 2015.

14 “Baseball: The Players of 1873. Outfielders,” New York Clipper, March 28, 1874.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 As an outfielder, Hall’s career fielding percentage (.856) was slightly above the league average (.824). His Range Factor per 9 innings of 2.17 and Range Factor per Game of 2.19 were also above the league average (RF/9: 1.99, RF/G: 2.01). Per baseball-reference.com, baseball-reference.com/players/h/hallge01.shtml.

18 “Baseball: The Players of 1873. Outfielders.”

19 “Boston vs. Mutual,” New York Clipper, May 9, 1874.

20 “Baseball: The Grand International Tour,” New York Clipper, March 7, 1874.

21 Box scores are available for only 9 of the 15 games played in Europe. Eric Miklich, “1874 World Base Ball Tour,” 19cbaseball.com/tours-1874-world-base-ball-tour.html.

22 “Base Ball.” Times of London, August 7, 1874.

23 GRANDMOTHER. “Base-Ball.” Times of London, August 13, 1874.

24 On the first major-league game, see John Zinn, “April 22, 1876: A New Age Begins With Inaugural National League Game,” in Bill Felber, ed., Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century (Phoenix: Society for American Baseball Research, 2013), 97-99.

25 “Baseball: Athletic vs. Cincinnati,” New York Clipper, June 24, 1876.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Not enough substantial evidence exists to credit Hall with hitting the first cycle in professional baseball. In addition to the Clipper’s account, the June 15, 1876, Cincinnati Enquirer states that Hall totaled 14 bases (four for a home run, nine for three triples, and one for a single). The Times of Philadelphia, June 15, 1876, credits Hall with a home run, two triples, a double, and a single (totaling 13 bases). Major League Baseball Historian John Thorn agrees with the information provided in both the Clipper and Enquirer. The accepted first cycle in the major leagues was completed by Curry Foley in 1882.

29 David Vincent, Home Run: The Definitive History of Baseball’s Ultimate Weapon (Dulles, Virginia: Potomac Books, 2007), 6.

30 William A. Cook, The Louisville Grays Scandal of 1877: The Taint of Gambling at the Dawn of the National League (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005), 78.

31 Ibid.

32 Cook, 84.

33 Cook, 124.

34 Cook, 130.

35 Ibid.

36 Cook, 137.

37 Cook, 139.

38 Ibid.

39 Cook, 139-141. George Hall’s testimony: “About three or four weeks after Al Nichols joined the Louisville Club, he made me a proposition to assist in throwing League games, and I said to him: ‘I’ll have nothing to do with any League games.’ This proposition was made before the club went on its last Eastern trip. He made the proposition to throw the Allegheny [Pittsburgh] game, and I agreed to it. He promised to divide with me what he received from his friend in New York, who was betting on the games. Nichols and I were to throw the game by playing poorly. While in Chicago, on the club’s last Western trip, I received a telegram from Nichols, stating that he was $80 in the hole, and asking how he could get out. I told Chapman that this dispatch was from my brother-in-law, who lived in Baltimore. I did not reply to the dispatch. Devlin first made me a proposition in Columbus, O., to throw the game in Cincinnati. He made the proposition either in the hotel or upon the street. We went to the telegraph office in Columbus, and sent a dispatch to a man in New York by the name of McCloud, saying that we would lose the Cincinnati game. McCloud is a pool-seller. The telegram was signed ‘D & H.’ We received no answer to this telegram. I did not know McCloud. Devlin knew him. McCloud sent Devlin $50 in a letter, and Devlin gave me $25. One of us sent a dispatch to McCloud from Louisville saying, ‘We have not heard from you.’ He sent then sent the $50 to Devlin; this was the 1-0 Cincinnati game. We telegraphed to McCloud from Louisville that the club would lose the Indianapolis game. I never received any money for assisting in throwing this game. I think it was the 7 to 3 game. Devlin said that he did not want to sign the order to have his telegrams inspected; said it would ruin him. There was another game Nichols and I threw. It was the Lowell Club of Lowell, Mass. He and I agreed to throw it. He did all the telegraphing. Never got a cent from Nichols for the games he and I threw. My brother-in-law has often said I was a fool for not making money. He has said this for several years past. His talking this way caused a coldness between us. When I was in Brooklyn the last time he asked me if we could not make some money on the games, and I told him I would let him know when we could. He bet on the Allegheny game and lost. Telegraphed him from here about the Indianapolis game. Had a talk with him in June, I think in Brooklyn, about selling games. Have sent two or three telegrams to him – not over three. His name is (Frank) Powell, and he lives (at 865 Fulton Street) in Brooklyn. Nichols first approached me about throwing games. Nichols asked me, on the last trip, if I could get somebody to work Brooklyn for me. I can’t tell you where it was that Nichols first approached me about throwing league games. When I told him that I would have nothing to do with League games, I meant that I would go in with him on outside games. I made the proposition about the Cincinnati game to Devlin. Last night I said he made it to me. I made the proposition in Columbus. Nichols spoke to me in Cincinnati about selling the Cincinnati game, and I said I would see about it. Nichols said: ‘George, try and get Jim in.’ He suggested that I should write a letter to Devlin. Devlin was not in the room when I wrote it. In the note to Devlin I think I said: ‘Jim how can we make a stake?’ I left the note on the marble-top table in our room at the Burnett House, Cincinnati. When I next saw Devlin he was in the room putting on his ball-clothes, and it was there that he said: ‘George, do you mean it?’ And I said: ‘Yes, Jim.’ After Devlin accepted the proposition I told Nichols that Jim was in it. Nichols was not in with us on the Cincinnati game. Think I wrote the letter to Devlin in Columbus, but won’t be certain. Think I destroyed the note at that time. Did not take it out of his pocket two or three days afterwards and destroy it. Am certain of this. Never got a cent for the Indianapolis game. Devlin said that he had never heard from McCloud about the money for it. Received but $25 from Devlin.”

40 “Baseball: The League and Its Work,” New York Clipper, January 20, 1877.

41 “Baseball: League Association Convention,” New York Clipper, December 15, 1877.

42 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: Free Press, 2001), 15.

Full Name

George William Hall

Born

March 29, 1849 at Stepney, London (United Kingdom)

Died

June 11, 1923 at Ridgewood, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.