George Yeager

“A ball player entertains thousands of people who go to see him at the ball grounds. But he also entertains millions who read about him in the newspapers,” wrote Olympic athlete and nationally syndicated journalist Robert Edgren toward the end of baseball’s Dead Ball Era.1 As one newspaper commented, George Yeager was “one of those quick thinking players … always ready to grasp at anything to keep the crowd in good humor.”2 However intentionally, Yeager also found many ways to enliven the nation’s sports pages. Often, though, his conduct caused consternation for umpires, management, and crowds during away games.

“A ball player entertains thousands of people who go to see him at the ball grounds. But he also entertains millions who read about him in the newspapers,” wrote Olympic athlete and nationally syndicated journalist Robert Edgren toward the end of baseball’s Dead Ball Era.1 As one newspaper commented, George Yeager was “one of those quick thinking players … always ready to grasp at anything to keep the crowd in good humor.”2 However intentionally, Yeager also found many ways to enliven the nation’s sports pages. Often, though, his conduct caused consternation for umpires, management, and crowds during away games.

George J. Yeager was born in Cincinnati to Henry and Anna (Leistner) Yeager on June 4, 1874.3 Henry was a Cincinnati native and Anna was an immigrant from Germany. Cemetery records indicate that Henry served in the Ohio Volunteer Infantry during the Civil War. In the 1880 census George had three sisters and in the 1900 census three younger siblings were still living with their widowed mother. Anna had 14 children but only six were living at that point. The youngest was his only surviving brother, Robert.

Based on city directories, George grew up west of downtown within a mile of the Ohio River. The 1880 census specified that Henry worked at a distillery. George attended school, and the 1940 census indicated that the highest grade he completed was eighth. In 1890 George Yeager had a separate entry in a city directory for the first time. His occupation was “mach. hand” and two years later it was spring maker. In 1893 he was listed as a ballplayer.

One team on which Yeager played was the Shamrocks. It was the only Cincinnati-area team mentioned in a Boston Herald profile of him a few years later.4 In 1891 one of their pitchers whom Yeager caught was Tom Sullivan, a recent major leaguer.5 That season Yeager also caught former Beaneater Dick Conway, and one newspaper article implied that the Shamrocks had several former NL players.6 The Poplar Stars were the other Cincinnati team with which Yeager was most strongly associated, primarily by Hugh Fullerton, a founder of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America. In 1906 Fullerton drew attention to the Poplar Stars among teams that produced multiple professional ballplayers, including Yeager and Barry McCormick.7

According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, George Yeager began his professional career with a club in Celina, Ohio, about 100 miles north of Cincinnati. The Herald profile said he was with that team starting in 1892.8 A box score in late September of 1892 showed Yeager batting cleanup for Celina and playing second base. He did likewise in mid-October against none other than the Cincinnati Reds, in Celina before 5,000 fans, and managed one of his team’s four hits while being shut out by Ice Box Chamberlain.9

Yeager, who was just 18 years old, continued with Celina in 1893. One box score in June had him batting second and playing second base again, but on July 2 he was the catcher in their first loss of the season, which was covered by Chicago, Indianapolis, and Cleveland newspapers.10 He soon saw additional duty behind the plate for Celina.11 At the beginning of August, the Celina team united with three others to form the Northwestern Ohio League, with each club to play 16 games to determine a regional champion.12 By then Yeager had returned primarily to second base. He reportedly considered himself a better infielder than catcher, and preferred to play second base barehanded. In any case, he displayed enough power that season to be given the nickname “Home Run.”13

In April of 1894 Yeager became the starting catcher for a team in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania.14 The club won its first game, at home on May 4 against a nine from a nearby college. Yeager was both acclaimed and scolded in Chambersburg’s newspaper: “He is one of the best catchers Chambersburg has ever had but he should confine himself to catching and not abuse the umpire as he did yesterday,” advised the paper. “Chambersburg is not accustomed to this and Yeager’s popularity as a catcher will be seriously impaired unless he learns to talk less and, when he does talk, in a more gentlemanly manner.”15

On May 12 he was involved in a fistfight that was big news locally. Around midnight a number of men were gathered at Lewis Forney’s cigar shop. A man named George Gruse tried to persuade a local named Charles Grove to fight Yeager. Ultimately Gruse challenged Yeager himself. “Yeager, it may be remarked here, gave Gruse a very severe beating,” wrote the Valley Spirit in its lengthy coverage. Forney threatened to use a baseball bat on anyone who interfered. Thus, when it appeared Grove was about to swing a beer bottle at Yeager, Forney struck. Grove sustained a skull fracture and vomited blood for hours.16 Forney was charged with assault and battery but Yeager also had to face authorities in a local courtroom. His case was dismissed because no complainant appeared.17

Yeager resumed his catching duties, including on May 18 and 24 against a team from the Carlisle Indian School.18 Within a few weeks he jumped to a team that had been in the Connecticut State League, representing New Haven. His first game with them was on June 28.19 The league had disbanded around the middle of the month but the New Haven team was already in turmoil at the beginning of June when players’ salaries were cut from $50 per month to $2 per game.20 High points during Yeager’s brief stay with New Haven included getting to test himself against the Springfield (Massachusetts) Eastern League team on July 3 and a complete-game win the next day, 10-4, as a pitcher against a team from nearby Meriden.21

Before the middle of July Yeager was back with Chambersburg, and in a game on July 13 he had four hits, including a homer and double. Nevertheless, his return lasted only about 10 days. “George Yeager, catcher for the Chambersburg club, has been released and left to-day for his home in Cincinnati,” a Carlisle newspaper reported on July 23. “Umpires in the valley towns will now feel perfectly safe since George has gone.”22

In less than a week Yeager was playing professionally with the Brockton (Massachusetts) team of the New England League.23 On August 2 he was already making enemies. “Yeager, the Brockton catcher, did a mighty mean trick … with the apparent intention of injuring the umpire,” said a newspaper. Yeager allegedly made no effort to catch one fastball and instead bent down to let it sail past him, though the ump dodged it. “This was a disgraceful performance and Yeager deserved severe punishment,” the account concluded.24

Yeager’s best game with Brockton might have been at home versus Pawtucket on August 22, when he went 4-for-4 with two doubles and three runs scored. Three days later the Brockton club disbanded, and Yeager was immediately signed by Pawtucket.25 When the New England League’s season concluded about two weeks later, Pawtucket didn’t hesitate to include Yeager among 15 players it reserved for the next season.26 The Pawtucket Tribune said he was “the fun maker of the team since he joined it and never failed to keep the boys in good humor.” As players dispersed after their final game and he went to catch a train, the Tribune reported, he “bid his friends adieu as follows: ‘The boy stood on the railroad track. He did not hear the bell. Farewell!’”27

During that offseason George Yeager said goodbye to bachelorhood. According to Kentucky marital records, he married 19-year-old Tillie Stadtlander on March 11, 1895, in Newport, just across the Ohio River from Cincinnati. In the 1893 and 1894 Cincinnati city directories, she was a laundress living with her parents.

Yeager continued with Pawtucket. Early success included home games on May 4 when he had five hits, including a double and two homers, and on June 8, when he hit a two-out grand slam. Later in June he was singled out by sportswriters for a very different reason when he was ejected from a road game for throwing a broom at the umpire. At home on July 8 one daily reported he was fined $10 by a different umpire “for insolent language and threatening with the bat.” Three days later he was back to making news for a good reason, when he went 5-for-5 in a home game.28

Yeager received some high praise from sportswriters in Boston. For one, Tim Murnane of the Globe considered him ready for the National League. Another endorsement was more specific: “Those managers who are searching for catching talent for next year would do well to look over Yeager of the Pawtuckets, who has been playing phenomenal ball this season,” wrote the Herald. “He is not only a hard hitter, but is represented as being a magnificent thrower to bases.”29

When the New England League’s season ended on September 7, Yeager was in the top 10 for batting average, with a mark of .360. In 94 games he scored 99 runs. In 78 of those games he played catcher, and his 102 assists led the league (19 more than the runner-up), but his .912 fielding percentage was the lowest among regulars at the position.30

Right after the regular season, the circuit’s top two teams, Fall River and New Bedford, were half of a temporary league of sorts that had historical significance. They were joined by an independent club in Newport, Rhode Island, plus a trailblazing African-American nine, the Cuban Giants, which featured future Hall of Famer Frank Grant. Each team was to play at least 11 games. Fall River immediately recruited Yeager to beef up its lineup. The first time Yeager faced the Cuban Giants was on September 13 in a 16-9 win for Fall River.31

Yeager returned for a third season with Pawtucket in 1896. On May 20 he added to his career tally of ejections, but that time, at least, his manager joined him. Little more than two weeks later, he was back to making news for the best of reasons when he homered twice in an 11-inning game won by Pawtucket. During the first half of August Yeager was insubordinate and thus fined “$25 for giving unsolicited advice to his manager,” as the Boston Herald put it, and toward the end of the month he became so angry catching Pawtucket’s pitcher during a game that he was ordered to switch positions with their right fielder.32

What surely mattered more was Yeager’s offense. In 98 games he scored 113 runs, stole 36 bases, hit 24 homers, batted .345, and slugged .604.33 As a result of this output, Yeager was purchased by the Boston Beaneaters on September 5. Two days later, just before leaving to join Boston, he celebrated dramatically in the second game of a three-team doubleheader. In the seventh inning his team trailed by a run when he stepped up to bat with the bases full. A fan clamored for “a farewell home run,” and Yeager proceeded to hit the very first pitch over the left-field fence for a decisive grand slam.34

Before appearing in a regular-season Beaneaters game, he played in several exhibitions.35 Yeager then made his major-league debut, at the age of 22, on September 25, 1896, in Washington before 3,786 fans. “Tom Tucker was out of condition, so Yeager covered first base,” noted the Boston Globe. “His work was equal to the best efforts of Tucker, and he played the bag as though he belonged there regularly.” He batted fifth, and his team led by just one run in the seventh inning when he faced Doc McJames, a future 20-game winner. Yeager singled and eventually scored an insurance run that helped Boston prevail, 6-3. He batted once late in the next day’s game and that was his final action for 1896.36

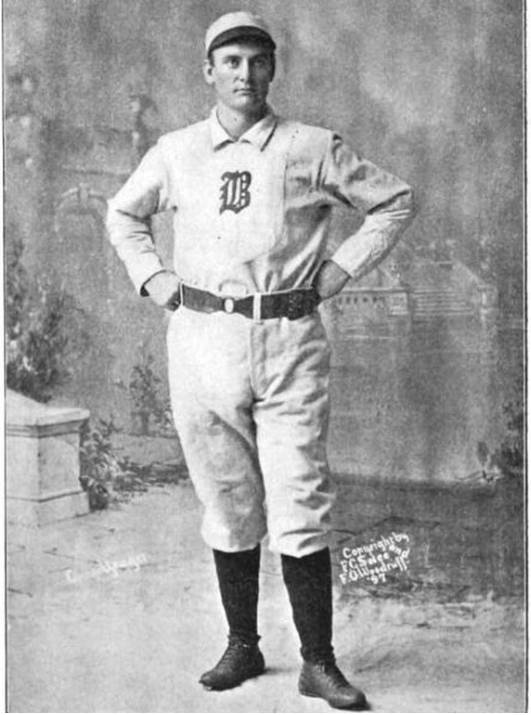

In mid-February of 1897 it was announced that Yeager had signed a contract to continue with Boston.37 Shortly thereafter the Boston Post quoted him at length:

“I signed as a catcher,” said Yeager, “and I have heard nothing to the contrary. However, I am willing to play anywhere or do anything to help the team. I am going to use part of my advance money in getting into condition. I realize that this is my chance. I have been in a minor league for three years, and this is my first opportunity to get to the front.”38

At the start of the regular season, Yeager’s height and weight were logged as 5-feet-8½ inches and 175 pounds.39 An early highlight came when the Beaneaters first played the Reds, in his hometown on May 27. He was the starting catcher, and though he was the only player in Boston’s lineup to go hitless that day, he was cheered “lustily” at one point just for reaching first base on a force out. Still, the best display by the “faithful adherents of the house of Yeager” came earlier in the contest. “When he first went to bat they sent out to their idol a six-foot stand of flowers and a diamond ring,” reported the Globe.40

Yeager soon achieved a milestone, in a home game vs. St. Louis on June 1: He hit his first major-league home run, off Bill Kissinger. His only other homer that season came on June 28. Two days later disaster struck. Boston hosted Brooklyn, and in the fourth inning rookie pitcher Jack Dunn collided with Yeager during a play at the plate. Yeager suffered a broken bone on the back of his catching hand, and one Boston paper immediately declared that he would be out for at least three weeks.41

Yeager ended up spending about five weeks back home in Cincinnati and rejoined the Beaneaters around August 3. At first he only coached baserunners, and the Globe teased that he “waltzed around the coaching lines like a dancing master on his benefit night.” By August 18 he still hadn’t played, and at that point he was loaned to Providence in the Eastern League.42 In 11 games for the Grays, he hit .286. A month later Yeager returned to the Beaneaters in the thick of a remarkable pennant race, and he quickly made a big splash in a crucial win at home against New York on September 18. As the Herald noted, “Yeager got his base every time he came to the bat – twice on balls and twice on hits.” One of those hits was a triple. He tripled again in a win against Brooklyn three days later.43 Those were his primary contributions toward taking the championship from Baltimore in the season’s final weeks.

Yeager spent all of 1898 with the Beaneaters. One early result was his inclusion in an overview of players’ quirks and traits. Readers of the Globe learned that he spent “most of his leisure time in reading scientific books,” foreshadowing his career change a decade later.44 Much more substantively, he was subjected to a lengthy assessment by the Herald in early June. That daily wrote in part:

“Yeager has shown great improvement in his work this season. He handles himself far better behind the bat than he did last season. He throws far more accurately and easily, and it is a lucky base runner who can get to second on him if he gets but half a show from the pitcher. In his hitting Yeager has greatly improved. He faces the pitcher with a great deal of confidence. Yeager is a far better man than many a catcher working regularly in the league today.”45

About a week later, the Herald noted that Yeager had hit safely in eight of his first nine games; his batting average was .323. On August 8 the paper mentioned that he had again hit safely in eight of his nine most recent games.46 Alas, Yeager entered a rough stretch later that month. At home on August 22, he was playing first base against Cincinnati when a rally-ending groundout was undone after one of the Reds insisted Yeager didn’t have a foot on the bag. He protested the changed call and was ejected. In Chicago two days later, he tried to field a sharply hit grounder only to have it strike him in the eye, which necessitated a hospital visit. Then at home on September 5 he broke a small bone on the back of his throwing hand in the first inning of a doubleheader and was projected to miss a week.47

Yeager returned at the start of a doubleheader at home on September 26 against Brooklyn. He came to bat with the bases jammed in the first inning and received an ovation, then responded by singling in two runs.48 Boston never relinquished its early lead and won both games to increase its lead in the standings over second-place Baltimore to 4½ games with 14 games remaining. Boston clinched the pennant soon enough, and Yeager was again a champion. He played in 68 games and hit .267.

The regular season lasted until October 15 and Yeager wasn’t feeling well, so he left for home immediately. The next evening he visited the Cincinnati Enquirer, which printed an extensive interview. He sang the praises of starting catcher Marty Bergen, then described tension within the team as a whole:

“After a losing game with that Boston team it was an easy matter to get a fight. All you had to do was look for one, and you would get it. They took defeat so much to heart that after a losing game everybody was ready to fight. That game of ours never knew what it was to let up. They played just as hard when they were 10 runs in front as they did when they were 10 runs behind.”

He also volunteered insights about his team’s use of secret signals: “We have very few signs. I’ll risk the remark that no team in the league had as few signs as the Bostons. We all understood each other.”49

On March 2, 1899, the Beaneaters purchased catcher Boileryard Clarke from Baltimore, and soon there was speculation that manager Frank Selee would farm out Yeager to Worcester in the Eastern League. This soon became reality. “Manager Selee has told George Yeager that he has decided to let him go to Worcester this spring,” wrote Tim Murnane. “Yeager seems perfectly willing to go there to play first base and catch a few games at the same salary he is receiving in Boston.”50

Opening Day for Boston was on April 15, 1899, and 10 days later Yeager was back with the team, albeit fleetingly. Bergen was away due to the death of one of his children, so Yeager caught in a loss at Philadelphia on April 25 and two days later batted against them once.51 Yeager was promptly returned to Worcester. In 90 games for that club he accumulated 26 doubles, 12 triples, 5 home runs, and 11 stolen bases, with a .316 batting average.

Despite his impressive performance, in Worcester on September 4 Yeager was removed by his manager for “insolence.”52 This kind of behavior again mattered little, because he rejoined Boston by September 8 to pinch-run for Billy Hamilton in the last inning of a loss. The next day he subbed for Hamilton in most of game in which Boston was one-hit by Doc McJames. That proved to be his last game ever for the Beaneaters.53 Yeager’s major-league career eventually continued, but his father didn’t live to see it. Henry Yeager died on November 9, 1899.54

Yeager joined Milwaukee of the American League for 1900, the season before that circuit was considered a major league. After 25 games he was hitting a lofty .388 when he suffered another substantial injury on May 26 in Detroit. While batting during the second inning he dropped to the ground to avoid being beaned by a pitch. He had to be carried off the field after sustaining what was described as badly torn ligaments in his left knee.55 He was still recuperating when Milwaukee released him in early July.56

Yeager continued in the American League in 1901, except with Cleveland. He made his regular-season debut in the team’s second game, on April 25, as catcher.57 He played 39 games with Cleveland, hit only .223, and was released on July 27. He returned to the National League, with Pittsburgh, on August 4. In 26 games his average improved, to .264.

During the following winter Yeager signed with the New York Giants. However, Sporting Life reported that he had recently “devised a most successful filter for the dark waters of the Ohio, and has met with such excellent success that he is putting in all his time at the filter manufacturing business just now, and is not giving base ball much thought.” In fact, Yeager helped patent that water filter.58 About a month later he also received atypical newspaper attention for his ability to communicate via sign language. He was quoted in detail about having had a deaf-mute roommate during one of his minor-league stints, and as a result he quickly befriended Luther Taylor, deaf pitcher of the Giants.59

After 39 games Yeager had a .204 average and the Giants released him on July 17, 1902. A week later the American League’s Baltimore Orioles signed him. He hit .184 in 11 games for them and was released on August 7. It turned out that his final major-league game was on August 5 in a loss at St. Louis. Ironically – for someone with a history of early exits from games due to his temper – he didn’t enter the game until the eighth inning because starting catcher Aleck Smith was ejected for arguing a call despite having full justification for doing so, the St. Louis Republic conceded.60

Yeager soon joined Minneapolis of the minor-league American Association and in 35 games he hit .328. He continued with them in 1903, and on May 13 he was named captain and manager.61 Toward the end of August he made headlines nationwide at the end of a game in Toledo during which he challenged the umpire and at one point flung a ball over the fence. A group of boys harassed him after the contest, and he threw the broom used for sweeping the plate at one of them. When fans nearby saw the 10-year-old take a tumble, they reportedly went after Yeager with stones and clubs. Policemen rescued him but charged him with assault and battery.62 Regardless, that season was a good one for Yeager at bat as he averaged .310 in 106 games.

On the other hand, Minneapolis finished near the bottom of the AA with a record of 50-89,63 and in 1904 Yeager played for another team in that circuit, Columbus. He played in 123 games for the Senators and hit .249. In 1905 he had short stints with two more AA teams, Toledo and St. Paul. In June he umpired an AA game in Louisville. Locals disapproved of his called third strike that resulted in a loss to St. Paul, and as he left the grounds he was whacked over the head with a beer bottle, punched in the face by a second fan, and struck with a baseball by a third.64 Less than a week later he jumped to Montgomery of the Southern Association.65

Yeager rejoined Minneapolis in 1906 and played in 78 games. In May he was coaching baserunners and added to his career total of ejections, and in midseason he received some attention when a teammate popped a foul near Minneapolis’s bench during a game. Yeager tried an old trick of rattling the bats to distract the fielder who tried for a putout, and the ploy worked.66

In 1907 and 1908 Yeager played for Des Moines in the Western League. It was apparently between those two seasons that he completed a degree in veterinary medicine, after which he was occasionally called Doc Yeager.67 As of 2019 baseball-reference.com listed a “Yeager?” on the roster of the Peoria Distillers of the 1908 Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League; that was George’s later team that season.68 Yeager played for St. Paul a second time in 1909, but by early August his role was reduced to advance scout due to what basically became a career-ending injury. Fittingly, shortly before that it was reported that he had been “cutting up boyish pranks all the time.”69

A 1909 Cincinnati city directory identified Yeager as a ballplayer but in the 1910 census his occupation was veterinarian. That census also revealed that he and Tillie had had a baby at some point, though by then the child was deceased. Records of the cemetery where George and Tillie are buried do not include a child of theirs.70

Not surprisingly, being a veterinarian in Cincinnati didn’t keep Yeager away from baseball entirely. By mid-1911 he had been signed to umpire in the local Saturday Afternoon League.71 City directories continued to list him as a veterinary surgeon through 1918 but by 1920 he was clerking in a yardmaster’s office for the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad. He remained in that field for the rest of his life. During 1931 and 1932, when he was past the age of 55, he was among numerous players invited to participate in old-timers’ games at Redland/Crosley Field, though he wasn’t named in coverage after they were played.72 Yeager died of a cerebral hemorrhage on July 5, 1940. He was survived by his wife and his brother Robert. Tillie died in 1944.73

How does one sum up George Yeager’s personality as a baseball player? Newspapers happened to do that late in his professional career. For example, at least two shared the Decatur Review’s assessment in 1908 that he had “much of the earmarks of a rowdy.”74 Much more recently, in one book baseball historian David Nemec called Yeager “an extreme extrovert who yammered unremittingly about himself” and in another summed him up as “egomaniacal.”75 Yeager probably would have preferred the summation one paper employed just before his final season in the high minors: “comedian.”76

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Robert Edgren, “R. Edgren’s Column,” Evening World (New York City), July 2, 1918: 10.

2 “Weather Too Chilly,” Cleveland Leader, April 11, 1901: 6.

3 His marriage license, draft registration card during World War I, Social Security application in 1937, and death certificate all agree that he was born in 1874, though the latter showed June 5 as the date. Other sources put his birth a day earlier, on June 4, 1873. For example, see George V. Tuohey, A History of the Boston Base Ball Club (Boston: M F. Quinn & Co., 1897), 158.

4 “League Games Now,” Boston Herald, April 18, 1897: 17. See also Jack Ryder, “Passing of the Millcreek Bottoms,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 1, 1905: 8.

5 “The Shamrocks Still Winning,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 27, 1891: 2. This article specified that “Sullivan, late of the Kansas Citys,” had hurled a one-hitter, and the paper also mentioned his stints with Columbus, Atlanta, and Birmingham, all of which applied to Tom Sullivan. His catcher, “Yaeger,” had two doubles and a single. “Jaeger” was another spelling in coverage of Shamrocks games during 1891.

6 “Shamrocks Beaten by Peru Again,” Indianapolis Journal, September 6, 1891: 5. In September of 1891 another local team, the Elliotts, had a catcher named Yeager for at least one game, according to “Base Ball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 23, 1891: 2.

7 Hugh S. Fullerton, “Base Ball on the Lots,” Washington Evening Star, October 22, 1906: 9. Hugh S. Fullerton, “Ball Players Like Rain,” Chicago Sunday Tribune, June 9, 1907: II, 4. Jack Ryder, “Passing of the Millcreek Bottoms,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 1, 1905: 8. The Poplar Stars apparently were under the age of 20, at least in 1891, according to “Gossip,” Cincinnati Post, April 14, 1891: 4. In the 1907 article Fullerton wrote vividly about a game during April of an unspecified year in which Yeager, McCormick, and the rest of the Poplar Stars played “against Jake Stenzel’s team. This was before Jake ever broke into fast company.” The site was the Liberty Street bottoms ballpark along Mill Creek, very close to where Yeager grew up. The Ohio River had caused extensive flooding nearby, and late in the game someone on Stenzel’s team hit a fly to left field just as a surge from the creek pushed the left-field wall inward dramatically. As a result, what might have been an easy out instead cleared the field of play. The umpire reportedly ruled it a game-tying homer and then declared the game over due to the wet grounds. (Because it was an amateur game, it may not have been reported on by any Cincinnati newspapers in the immediate aftermath.) Given that Stenzel began his minor-league career in 1887 and made his NL debut in 1890, it seems very unlikely he and Yeager ever played amateur ball together. Regardless, Fullerton wasn’t off base by associating that ballpark with Yeager; two years earlier a Cincinnati journalist did as much when the ballpark was being phased out, and he named additional major leaguers who honed their skills there in addition to Yeager.

8 “George Yeager,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 9, 1940: 9. “League Games Now,” Boston Herald, April 18, 1897: 17.

9 “Snapped,” Lima (Ohio) Daily Times, September 30, 1892: 8. This game ended prematurely when the opposing pitcher broke his arm while throwing. “Big Turn-Out,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 17, 1892: 2. See also “Baseball,” Cincinnati Post, October 17, 1892: 4.

10 “On the Diamond,” Delphos (Ohio) Weekly Herald, June 22, 1893: 3. “Sports Here and There,” Chicago Daily News, July 3, 1893: 2. “Muncie, 6; Celina, 1,” Indianapolis Journal, July 3, 1893: 3. “Other Games. Celina’s First Defeat,” Cleveland Leader, July 3, 1893: 3.

11 For examples, see “Celina Won,” Cleveland Leader, July 5, 1893: 6; “Celina, 12; Findlay, 8,” Daily Inter Ocean (Chicago), July 13, 1893: 4.

12 “Another Base Ball Infant,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 3, 1893: 5. The other three cities were Columbus Grove, Delphos, and Findlay. The article noted that nearby Fort Wayne, Indiana, might provide a fifth team in the circuit and thus cause the league’s name to change.

13 For additional examples of Yeager in box scores at second base, see “On the Diamond,” Delphos Weekly Herald, July 20, 1893: 3, and August 3, 1893: 2; “Seventh Inning,” Elwood (Indiana) Daily Press, August 21, 1893: 1. See also David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 288.

14 “Work on the Ballfield,” Valley Spirit (Chambersburg, Pennsylvania), April 25, 1894: 1. David Nemec said that Yeager spent part of 1894 with Celina. Because Yeager had stints with four other clubs documented herein, it’s difficult to envision when Yeager would have had time to return to Celina.

15 “7 to 2,” Valley Spirit, May 9, 1894: 8. The opposing team was from Franklin and Marshall College of Lancaster, Pennsylvania.

16 “His Head Broken,” Valley Spirit, May 16, 1894: 5. See also “Hit by a Base Ball Bat,” Hagerstown (Maryland) Daily Herald and Torch Light, May 15, 1894: 4.

17 “With the Policemen,” Valley Spirit, May 23, 1894: 6. Forney was charged with assault and battery but fled, only to be returned from Illinois. In August he was one of seven prisoners who escaped the local jail while awaiting trial. See “Franklin Has a Leaky Jail,” Philadelphia Times, August 21, 1894: 1.

18 “A Tie Game,” Valley Spirit, May 23, 1894: 8. “A Victory,” Valley Spirit, May 30, 1894: 3.

19 “Base Ball Gossip,” Harrisburg Star-Independent, June 27, 1894: 5. “New Haven 6, Willimantic 2,” New Haven (Connecticut) Morning Journal and Courier, June 28, 1894: 1. “New Haven 15, Edgewood 8,” New Haven Morning Journal and Courier, June 29, 1894: 1.

20 “At Savin Rock Shore,” New Haven Morning Journal and Courier, June 18, 1894: 4. “Players’ Salaries Cut,” New Haven Morning Journal and Courier, June 5, 1894: 2.

21 “Eleven to Eight,” New Haven Evening Register, July 4, 1894: 3. “New Haven Wins a Game,” New Haven Evening Register, July 5, 1894: 3.

22 “Some Fresh Baseball Notes,” Valley Spirit, July 11, 1894: 8. “Undines Defeated,” Carlisle (Pennsylvania) Evening Herald, July 14, 1894: 1. “By-By, Yeager,” Evening Sentinel (Carlisle, Pennsylvania), July 23, 1894: 3.

23 “Thirteen-Inning Tie Game,” Boston Herald, July 28, 1894: 2.

24 “Another Easy Victory,” Bangor (Maine) Daily Whig and Courier, August 3, 1894: 3. However, six months later that same paper characterized Yeager very differently when it believed that the local team had signed him. “He made a good impression when playing in this city,” according to “Base Ball Notes,” Bangor Daily Whig & Courier, February 1, 1895: 3.

25 “Brockton 14, Pawtucket 6,” Boston Globe, August 23, 1894: 3. “Brockton Team Gives Up,” Boston Herald, August 26, 1894: 4.

26 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, September 11, 1894: 2. The next day that paper published New England League fielding statistics (excluding catchers) and batting statistics. Column headings for the batting statistics were omitted, but context clues indicate that the first four columns were for games, runs, hits, and total bases. If so, as a batter for Brockton and Pawtucket combined Yeager played in 37 games, scored 25 runs, had 39 hits good for 48 total bases, and a batting average of .260. Five days later the paper published additional statistics for batteries, and in 27 games as catcher for Brockton and Pawtucket he had 158 putouts, 56 assists, 21 errors, 11 passed balls, and a fielding percentage of .911. See “New England Baseball,” Boston Globe, September 12, 1894: 2, and “New England League Work,” Boston Globe, September 17, 1894: 2.

27 “Made ‘Home’ Runs,” Pawtucket (Rhode Island) Tribune, September 17, 1894: 1. The article implied that Yeager was catching a train back home to Cincinnati, but three days later he was the umpire for a game hosted by the New England League’s champs in Fall River, Massachusetts. See “Those Exciting Intercity Games,” Boston Herald, September 21, 1894: 2.

28 “Main Clubs All Beaten,” Boston Herald, May 5, 1895: 4. “The Field of Sport,” Portland (Maine) Daily Press, June 10, 1895: 2. “Lewiston, 6; Pawtucket, 4,” Boston Journal, June 20, 1895: 3. “Slater’s Home Run,” Portland Daily Press, July 9, 1895: 3. “Pawtucket Made 32 Runs,” Boston Herald, July 12, 1895: 2.

29 “Personal,” Sporting Life, August 3, 1895: 2. “Around the Bases,” Boston Herald, August 31, 1895: 8. Most of the Herald’s assessment was lifted verbatim in “News and Comment,” Sporting Life, September 7, 1895: 2.

30 “New England Ball Players,” Boston Herald, October 8, 1895: 8.

31 “Base Ball,” Newport (Rhode Island) Mercury, September 7, 1895: 1. “Champion Fall Rivers Beaten,” Boston Herald, Sept 8, 1895: 7. “Fall River, 16; Cuban Giants, 9,” Boston Herald, September 14, 1895: 8.

32 “Leaders Lost,” Boston Journal, May 21, 1896: 4. “Over the Fence,” Boston Herald, June 6, 1896: 3. “New England League Tips,” Boston Herald, August 13, 1896: 8. “Base Ball,” Bangor Daily Whig & Courier, August 28, 1896: 1.

33 To help put his slugging percentage in perspective, only seven times during the 1890s did a major leaguer record a higher figure. See baseball-reference.com/leaders/slugging_perc_season.shtml; all of the occurrences were from 1894 to 1896.

34 “Bought Another Catcher,” Boston Globe, September 6, 1896: 4. Macque, “Pawtucket Pets,” Sporting Life, September 12, 1896: 13.

35 “Seven in Seventh,” Boston Globe, September 9, 1896: 9. “Down They Go,” Boston Post, September 12, 1896: 3. “Boston Loses,” Boston Post, September 15, 1896: 3. “Heavy Hitters Fooled, Boston Globe, September 24, 1896: 9. The exhibition games were in Fall River; Orange, New Jersey; Wilmington, Delaware; and Paterson, New Jersey.

36 “Due to Stivetts,” Boston Globe, September 26, 1896: 2. “Failed to Hit Stivetts,” Washington Times, September 26, 1896: 3. “Senators Lost the Last,” Washington Times, September 27, 1896: 7. In contrast to the latter, the Globe’s box score credited Yeager with a sacrifice hit and thus no time at bat. See “Landed Fourth,” Boston Globe, September 27, 1896: 4.

37 “The Boston Team,” Boston Post, February 16, 1897: 3. The Post certainly expected this, as indicated in “General Sporting Gossip,” Boston Post, January 3, 1897: 19. See also “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, January 18, 1897:3.

38 “General Sporting Gossip,” Boston Post, February 21, 1897: 8.

39 “League Games Now,” Boston Herald, April 18, 1897: 17. In later years nasty or snide remarks were occasionally made about Yeager’s weight, such as in “Sporting Notes,” Worcester (Massachusetts) Daily Spy, May 13, 1901: 3. At one point he weighed 207 pounds, according to “Wore Out Grass Running Bases,” Minneapolis Journal, May 17, 1904: 14. However, his weight was listed as 190 in “Statistics of the Des Moines Champs,” Denver Post, April 6, 1907: 9.

40 “Biff and Run,” Boston Globe, May 28, 1897: 9.

41 “All Three,” Boston Daily Advertiser, July 1, 1897: 4. Details of Yeager’s major-league home runs are provided at baseball-reference.com/players/event_hr.fcgi?id=yeagege01&t=b.

42 “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 1, 1897: 2. “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, August 10, 1897: 3. “Echoes of the Game,” Boston Globe, August 20, 1897: 3. “Chipped Diamonds,” Evening Telegram (Providence, Rhode Island): August 20, 1897: 6.

43 “Easy for Boston,” Boston Herald, September 19, 1897: 4. “Yellow Ball,” Boston Globe, September 22, 1897: 7. Yeager also saw action during the postseason Temple Cup series won by Baltimore. In particular, in the last game, on October 11, he went 3-for-4. He tripled in the ninth inning and then scored the Beaneaters’ final run of 1897. See “Boston Loses,” Boston Journal, October 12, 1897: 3.

44 T.H.M., “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, May 1, 1898: 8. The author was Tim Murnane.

45 “Yeager’s Work,” Boston Herald, June 5, 1898: 13.

46 “On the Bleachers,” Boston Herald, June 13, 1898: 5. “On the Rubber,” Boston Herald, August 8, 1898: 8. On both pages there were team statistics a few columns to the right.

47 W.S. Barnes Jr., “Their Lucky Escape,” Boston Journal, August 23, 1898: 7. Ren Mulford Jr., “Western Dogs o’ War Astir,” Cincinnati Post, August 25, 1898: 2. “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, September 6, 1898: 9. See also “Senators’ Helping Hand,” Washington Times, September 6, 1898: 6.

48 “Two Games at South End,” Boston Globe, September 26, 1898: 7.

49 “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 17, 1898: 4. The paper consistently misspelled his surname as Yaeger.

50 “Baseball Notes,” Boston Globe, March 15, 1899: 4. T.H. Murnane, “Sunday Run,” Boston Globe, March 27, 1899: 5.

51 W.S. Barnes Jr., “Ragged Work,” Boston Journal, April 26, 1899: 3. T.H. Murnane, “Bad Licking,” Boston Globe, April 28, 1899: 3. See also a second article by Murnane on the same page, “Boston Uncomfortable.” Barnes reported that early in the game on April 25 Yeager was injured near the elbow of his throwing arm by a foul tip, and that it hampered him all game.

52 “Worcester Drops Two,” Boston Globe, September 5, 1899: 9.

53 “Echoes of the Game,” Boston Globe, September 9, 1899: 4. On the same page see also T.H. Murnane, “Without a Run,” though Yeager’s name didn’t appear in the accompanying box score. For a description of the one-hit loss see T.H. Murnane, “Hoodoo Reigns,” Boston Globe, September 10, 1899: 5.

54 “Frosted Fan Food,” Cincinnati Post, November 10, 1899: 2. Anna Yeager lived until late 1922, according to “Death Notices,” Cincinnati Post, November 29, 1922: 13.

55 “Milwaukee 4-Detroit 2,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 27: 16. “Slug Hard Take Game,” Milwaukee Journal, May 28, 1900: 10.

56 “Yeager Released by Milwaukee,” Pittsburgh Press, July 2, 1900: 5. On July 20 it was announced that the Omaha club of the Western League had signed him, but his name didn’t appear in any of their box scores until August 2 – as the umpire in a game against Sioux City. According to one Omaha daily, that same day their local team had released “Tim Hurst Yeager,” alluding to the famous umpire known for fairness but also a very short temper. See “New Men for Omaha Nine,” Omaha Evening World-Herald, July 20, 1900: 8. “Base Ball Gossip,” Evening World-Herald, August 2, 1900: 8. For the box score of the game in which Yeager umpired, see “Rourkes Slug the Soos” on page 7 of the latter paper.

57 “Team Not in Condition,” Cleveland Leader, April 26, 1901: 6.

58 “News and Gossip,” Sporting Life, April 12, 1902: 5. See also David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011): 289.

59 “Baseball Notes,” Washington Evening Times, May 16, 1902: 3.

60 “Browns Take Series from Unlucky Birds,” St. Louis Republic, August 6, 1902: 8.

61 “Yeager Is Manager,” Minneapolis Journal, May 14, 1903: 16.

62 “Yeager Makes Himself Obnoxious,” New Orleans Item, August 30, 1903: 1. This story went out via the Hearst News Service. See also “Yeager Yanked,” Sporting Life, September 5, 1903: 5.

63 “Lose the Last Game,” Minneapolis Journal, September 22, 1903: 8.

64 “Yeager Is Assaulted,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 12, 1905: 3.

65 “A Few Foul Tips,” Montgomery Advertiser, June 16, 1905: 10.

66 Frank E. Force, “On the Inside,” Minneapolis Tribune, May 10, 1906: 8. Frank E. Force, “On the Inside,” Minneapolis Tribune, July 1, 1906: 35.

67 “Yeager Reports,” Des Moines Daily News, April 3, 1908: 14. See also Ren Mulford Jr., “Mulfordisms,” Sporting Life, April 10, 1909: 11. Mulford named Frank “Noodles” Hahn as pro baseball’s other Doctor of Veterinary Science.

68 “With Ball Players,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, June 30, 1908: 3. “Peoria Gets Big Leaguer, Dubuque (Iowa) Daily Times-Journal, July 1, 1908: 7.

69 “Line ’o Dope,” Rock Island Argus, August 5, 1909: 3. “Around the A.A. Circuit. The ‘Old Doc” Quite a Kid,” Kansas City Star, June 24, 1909: 9. The latter quoted the Indianapolis Star.

70 See springgrove.org/geneology-search.aspx.

71 “New Umpires Signed,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 12, 1911: 8.

72 Jack Ryder, “Old-Time Ballplayers to Cavort Once More over Redland Diamond,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 9, 1931: 31. Tom Swope, “Old-Timers Will Gather at Cincinnati for Game,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1931: 3. Jack Ryder, “Heroes of Past Cavort Once More on Redland Diamond,” September 6, 1931: 15. “Former Red,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 4, 1932: 2-3. Jack Ryder, “Old-Timers Presence Inspires Rixey, Who Blanks Bucs,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 22, 1932: 9.

73 “George Yeager,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 9, 1940: 9. His cause of death was specified on his Ohio certificate of death. Details of Tillie’s death are accessible via springgrove.org/geneology-search.aspx.

74 “The Same in Springfield,” Illinois State Journal (Springfield), August 18, 1908: 6. Dubuque (Iowa) Daily Times-Journal, August 19, 1908: 5.

75 David Nemec, Major League Baseball Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1: The Ballplayers Who Built the Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011), 288. David Nemec, The Rank and File of 19th Century Major League Baseball: Biographies of 1,084 Players, Owners, Managers and Umpires (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2012), 94.

76 “Grand Stand Chatter,” Jonesboro (Arkansas) Daily News, April 10, 1909: 2.

Full Name

George J. Yeager

Born

June 4, 1873 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

July 5, 1940 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.