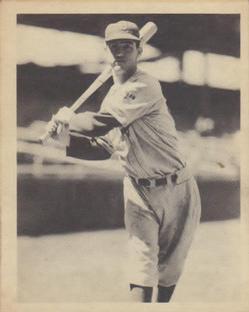

Goody Rosen

One of the most remarkable characteristics of Goodwin “Goody” Rosen is that the diminutive former National League All-Star spent the entirety of his career drawing strength from his identity as “the other” in baseball. On the one hand, Rosen was a Jew, one of only 25 Jews to play in the major leagues during the 1930s and one of only 27 Jews from the 1940s. As if his ethnicity did not already make him enough of an outsider, Rosen was also a Canadian, playing at a time when George Selkirk, all but forgotten today, served as the best ballplayer the Great White North could produce.

One of the most remarkable characteristics of Goodwin “Goody” Rosen is that the diminutive former National League All-Star spent the entirety of his career drawing strength from his identity as “the other” in baseball. On the one hand, Rosen was a Jew, one of only 25 Jews to play in the major leagues during the 1930s and one of only 27 Jews from the 1940s. As if his ethnicity did not already make him enough of an outsider, Rosen was also a Canadian, playing at a time when George Selkirk, all but forgotten today, served as the best ballplayer the Great White North could produce.

As Peter Levine remarks in From Ellis Island to Ebbets Field, his wonderful study of Judaism, immigration, and American sports, “Rosen carried a double burden as both a Canadian and a Jewish ballplayer.” Levine concludes that this ‘doubleness’ ultimately prevented Rosen from achieving the stardom his talent might have warranted. Given Rosen’s ethnicity and his general pugnacity, this may well be true. That said, it was these same characteristics that made the cigar-smoking, Yiddish-speaking traveling garment-salesman from the Toronto Annex one of the most beloved Canadian baseball players of his time.

Samuel and Rebecca Rosen came to Toronto from Minsk, to escape persecution from czarist Russia in the period preceding the First World War. Like many European immigrants of the time, the Rosens seem to have internalized an Old World mentality, as the Orthodox family retained a kosher home and Samuel and Rebecca produced eight children, the fifth of whom was Goodwin.

Like so many first-generation Canadian families, the Rosens found that success in the New World meant tailoring their religious practices to the secular mores of the traditionally Protestant, quickly modernizing culture of Toronto. Despite Rebecca Rosen’s professed Orthodox Jewish beliefs, the family was not always able to keep a kosher home, as the eating of forbidden foods was sometimes a matter of survival to the Rosen family. Furthermore, between selling newspapers to help make ends meet, as well as playing all manner of sports, Goody had little time for religion and was not even Bar Mitzvahed. That aside, Goody would retain an unconditional pride in his ethnicity throughout his entire life.

The Rosen family came to Toronto at a time in which Goody’s ethnicity could not, either in day-to-day life or the baseball world, be treated as a non-issue. While Montreal would have Canada’s largest Jewish community until the eve of the Quiet Revolution, Toronto (and North America in general) saw an explosion in its Jewish population during Goody’s childhood that thrust the importance of Jewish-Gentile interaction into the mainstream. While Toronto boasted a substantial Jewish population at the turn of the century (20% of Canada’s Jewish population), that number had almost doubled by the time of Goody’s birth, and, by the time Goody began playing baseball professionally, had doubled again.

Because of Toronto’s major Jewish influx, many of Toronto’s local baseball heroes were also Jews. While the Toronto Maple Leafs baseball club was uncompetitive for much of the 1930s, star players such as Izzy Goldstein and Harold “Whataman” Sniderman became local heroes to both Toronto baseball fans and the city’s Jewish community. The fact that a substantial number of Toronto’s homegrown star ballplayers were Jewish was significant to Goody, who, in 1984, bluntly stated his views on the place of the Jewish people: “I have always felt and believed that the Jewish people are far superior in every way to everyone else.”

In 1925, Goody became a student at his local high school, Parkdale Collegiate Institute, where he would first establish himself as an exceptional ballplayer. Like so many talented high school athletes, however, Goody was also a standout football player, though the only lasting legacy of Goody’s football playing was a broken nose, a physical emblem of the bullish attitude he would later become known for in his baseball career.

At the same time as he was playing on his high school baseball team, he was also playing in the Canadian Youth League as a 14-year-old member of the team that won the Canadian Amateur Baseball Championship. Because Toronto in the 1920s was, like any other major North American city, a highly-sectionalized series of ethnic immigrant “pockets,” Goody extended his ball playing focus beyond his high school, becoming a prominent member of the Jewish Fraternal Softball League. If nothing else, Goody’s time in the JFSL likely eased the burden any Jewish-Gentile tensions that might have arisen in the non-denominational high school and youth leagues.

A defining decision in Goody’s life came in the winter of 1930. Chatting with a friend and fellow local ballplayer while watching neighbors shoot a hockey puck up and down the ice, the two men decided to abandon their Toronto lives and hike over 2,000 miles to Florida, where they might try out for the winter league ball. Upon arriving in the Sunshine State, however, Goody and his friend found that no such league existed, and they promptly returned to Toronto.

But why might one see Goody’s failed expedition to Florida as a paradigmatic change in his life? Most importantly, the trip solidified in Goody’s mind, and the minds of those who knew him, that he was, in fact, a ballplayer by trade. With his aspirations clearly focused, Goody continued his attempts to catch on with a professional club, trying out with the minor league clubs in Little Rock and Memphis in 1931, being unsuccessful in each case.

While trying out for these low-level professional clubs, Goody also played on the non-professional Elizabeth Playground Lizzies team in Toronto, which allowed him to keep his skills sharp while trying to catch on professionally. His time with the Lizzies was important enough that Goody would often credit his success later in life to his coach on the Lizzies, Bob Abate.

Goody’s persistence and patience paid off in 1932, in his junior year with Elizabeth Playground. Having distinguished himself in Toronto’s non-professional baseball circles, Goody was invited to attend a tryout camp staged by the minor league Rochester Red Wings. Playing with Rochester in an exhibition game against the New York Giants, Goody collected two hits, a feat impressive enough to land him a spot, if only for a month, with the Red Wings. Though his play was not exceptional with his new club, the reason for Goody’s quick cut from the team was altogether galling. It was not for the quality of his play, but because the Red Wings had already decided Goody was not professional ballplayer material. Warren Giles, the business manager of the Red Wings and a future National League president, told Rosen “Son, you’ve got a lot of ability, but you’ll never be a ballplayer. You’re too small.” This would not be the last time Rosen faced this criticism.

In 1932, Goody was given another opportunity to catch on with a professional club, trying out with the minor league team in Binghamton, New York. Goody signed with Binghamton, and was sent to the team’s Stroudsburg affiliate. Unfortunately, the Inter-State League was disbanded on June 20, 1932, and the Stroudsburg team was forced to fold after a month and a half.

Mere weeks after Goody’s second attempt at a professional career, the most important event in the history of Toronto’s Jewish community took place. On the 16th of August, 1932, at Toronto’s Christie Pits baseball field, a riot broke out during a softball game between the Harbord Playground, a predominantly Jewish team, and a team representing St. Peter’s Church. During previous baseball games at Christie Pits, the Toronto Swastika Club had prominently displayed swastikas and yelled “Heil Hitler” at games played by predominantly Jewish teams. On August 16, however, racial tensions went from a simmer to a boil, and the seventh inning unfurling of a swastika banner touched off a riot that involved 8,000 people and saw violence in the streets last deep into the night.

The reverberations of the riot at Christie Pits, which Goody Rosen himself may or may not have been at (he was back in Toronto at this time), had enormous reverberations on Toronto’s entire Jewish community. As David Spaner points out in Total Baseball, the riot wasn’t only significant because of its racialist overtones, but also because it turned the game of baseball, so significant to young Toronto Jews in the 1930s, into an ethnic battlefield.

The impact of Goody’s ethnicity on his playing career should not be understated, as it was of great significance to fans, managers, coaches, fellow ballplayers, and Goody himself throughout the entirety of his playing career. During the 1930s and 1940s, Jews, especially in sports, were considered by non-Jews to be a curiosity or, at worst, an abomination. One of the silliest, and most telling, examples of the “otherness” of Jews in baseball at this time can be seen in an account from former American League MVP Al Rosen who, playing in the same minor league as Goody during the 1947 season explained that he and Goody were not brothers, and that he “used to get about 25 letters a day asking that question.” This example, though fairly benign, is indicative of the peculiar nature of Jews in baseball at this time.

To Peter Levine, the public and private images of being Jewish included, for people like Al and Goody Rosen, an assertive pride in being Jewish, regardless of formal Jewish training, as well as stressing exclusion and superiority above other groups. Goody, it is often said, was not simply willing but eager to ward off attacks on his ethnicity and religion. Commenting on the anti-Semitism Jews found on the ball field in the late 1930s, Goody commented defiantly that “we took care of ourselves, we gave as good as we got and we emerged stronger than ever. I’ve always, since I was a small kid, walked proudly that I was a Jew, and never took any crap, pardon the word, from anyone.”

In 1933, Goody caught on permanently in the professional ranks, signing with the Louisville Colonels of the American Association. Goody appeared at Louisville, only to be mistaken by the trainer as the batboy. So small was the 20 year-old outfielder that he wore his uniform bunched at the knees. From 1933 to 1936, Goody plugged away, failing to advance in the minor league ranks, a fact that, by 1937, was wearing on Goody’s patience. It was reported in February of that year that Goody wasn’t keen to return to the Colonels and had even returned his contract in an effort to have his rights traded to the Toronto Maple Leafs. Grudgingly, Goody signed his contract prior to the 1937 season and, in his final year in Louisville, hit .312 with 11 home runs and 80 runs batted in, being selected to the American Association All-Star Team in the process.

Fuelled by his antipathy for playing in the minor leagues, Goody showed unequivocally that he was ready for big league pitching. For his patience and productivity, the Louisville Courier-Journal chose Goody as the best outfielder in the history of the Louisville Colonels. At the close of the 1937 season, Goody was also voted the team’s most popular player in a radio station poll, and given a “Rosen Day” in Louisville.

Near the end of the 1937 season, the Brooklyn Dodgers called Goody up to the big club. Goody’s impact on the lackluster Dodgers was immediate, as he made his debut as a pinch-hitter in a doubleheader against the Reds. In the second game, Goody took center field in place of Johnny Cooney and collected two hits, a run batted in, and a stolen base. After his first week in the major leagues, Goody had already made a substantial impression, batting .454.

Goody’s fast start earned him semi-celebrity status in New York, as the New York Sun reported in early October that Brooklyn fans were already “keen” on their new center fielder. Goody’s successes and celebrity weren’t lost on his hometown of Toronto, either. He was thrown a celebration honoring his “accomplishments” on November 30, 1937, at Toronto’s King Edward Hotel, despite having completed a season in which he’d collected just 77 at-bats in 22 games with the Dodgers.

The 1938 season saw Goody continue his slow growth as a major league ballplayer. Despite being given a locker adjacent to then-Brooklyn batting coach Babe Ruth, Goody was a somewhat reluctant addition to the team. As was the case in the previous year, Goody played himself into the lineup and, by May, the Toronto Star reported that “earlier in the season the big town ball writers who cover the activities of the Dodgers only mentioned Rosen as ‘also on the lineup,’” though now “they’re writing feature stories about him.” Though Rosen hit a respectable .281, with 11 triples and a .368 on-base percentage over 473 at-bats, it was Goody’s defensive work that was making him a star. Despite playing only as a semi-regular, Goody ended up leading the National League in both fielding percentage (.989) and outfield assists (19).

Throughout the course of the 1938 season, Goody also refined his lifelong image as a nuisance to opponents. Throughout the course of the season, Goody broke up two no-hitters, one against Hal Schumacher and another against Bill McGee. At another point in the season, Goody had hits in eight consecutive at-bats, having it ended when the Cardinals’ Max Lanier forced Goody to ground out to Jimmy Brown.

Though he briefly led the league in batting average, Goody’s season was again truncated, this time by injury. When an on-field incident resulted in a tearing of the ligaments about Goody’s left ankle, the team doctor advised Rosen not to play. Unfortunately, manager Leo Durocher pushed Goody to play, resulting in Rosen’s average plummeting. Goody was sent down to the Dodgers’ minor league Montreal Royals club, but was recalled later that year.

Goody’s first go-around with the Dodgers ended in 1939, despite his having been the National League’s best defensive center fielder all three years. It should be noted that Goody was underpaid to the point that he was forced to supplement his income as a traveling salesman for the well-known Toronto tailoring firm of Tip Top Tailors. It would be another six years until Goody would have a season good enough to earn above-average pay for his above-average play.

Though Goody had played well in the late Thirties, his size would still have likely kept him out of the major leagues if it weren’t for the efforts of Hall of Fame pitcher Burleigh Grimes, a man to whom Goody owed nothing less than his career itself. Perhaps Grimes’s efforts on behalf of Rosen were simply due to Goody’s impressive on-field performance. It is also possible, however, that Grimes, who was an unimposing 5’10” and 175 pounds himself, saw some of himself in Rosen. Grimes maintained an active interest in Goody throughout the diminutive outfielder’s career, especially after taking the reins as manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers. It was, indeed, due to the Grimes’s efforts that Goody was promoted to the big league club in the first place and, after the promotion, it was reported in the September 17, 1937 edition of the Toronto Star that “Burley (Boiley) Grimes of the Brooklyn Dodgers boiled right over with ecstasy today in discussing Canada’s newest gift to big-time baseball.”

By October of 1938, however, Grimes was fired as manager of the Dodgers, only to take over as manager of Brooklyn’s minor league Montreal Royals club. Goody’s demotion allowed Grimes and Rosen to renew their acquaintance in 1939, however, when Goody was sent down to the Royals. Interestingly, Goody may have stayed in the majors if it weren’t for Grimes’s efforts, as Grimes, upon being asked whom he wanted sent to his club in exchange for outfielder Sam Parks (who was being called up to the big club), insisted that any package include Goody Rosen. While it may seem counterintuitive for Grimes to show his affection for Goody by bringing him back down to the minors, it is, at the very least, a testament to Grimes’s enormous affection for Goody.

Upon Goody’s optioning, along with pitchers Cletus Poffenberger and Gene Scott, to the International League Montreal Royals in June 1939, it was assumed by Goody that the move was temporary. On July 21, with the Royals in Toronto for a series against the Toronto Maple Leafs, friends and fans of Rosen held a celebration for the recently-demoted outfielder. Before a game in which he collected two hits against his hometown team, Goody was presented with a radio, a Bulova watch, a suit, a few Brill shirts, a floor lamp, a hat, and a sports jacket, as well as having a bouquet of flowers presented to him by Nan Morris, Miss Toronto of 1939.

At the end of the 1939 season, Goody, feeling healthy and ready to resume big league play, returned his contract, presumably one he believed did not fit his potential contributions to the team. When Dodgers general manager Larry MacPhail received Rosen’s contract back unsigned, MacPhail, a one-time supporter of Goody, sold Rosen’s contract to the Columbus Red Birds of the American Association. Goody and Columbus were an unnatural fit from the start, with Columbus Manager Burt Shotton telling Rosen “I’m going to cure you you’re a rebel and I’m going to put you in your place.” Rosen and Shotton’s relationship was always rocky, and Goody lasted only ten games with Columbus, hitting .212, leading to his being moved to the Syracuse Chiefs of the International League.

While Goody would never hit .300 in the next four years with Syracuse, he clearly found new life and quickly became one of the team’s most popular players, Rosen also served as the team’s official captain, leading the club to the Little World Series. Goody’s last year in Syracuse, 1944, was perhaps his worst, as he hit a paltry .261 and was on the verge of ending his career. The Second World War, however, provided spectacular opportunities for 4-F players, and the 1945 season would see Goody given the greatest opportunity of his professional life.

In the spring of 1945, Rosen felt discouraged enough to consider retiring from baseball rather than spend another year in Syracuse. It was Goody’s thought that he would go to Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Dodgers, and ask to be traded to his hometown team, the Toronto Maple Leafs. During spring training, however, Red Durrett, a starting outfielder for the Dodgers, ate tainted fish at the Bear Mountain Inn in Bear Mountain, New York. With Durrett immobilized by food poisoning, a temporary spot on the Dodgers roster opened up.

At the same time Durrett was opening up a roster spot, Chuck Dressen, then a coach on the Dodgers, was working with Goody on smoothing out a hitch in his swing. Dressen’s work with Rosen paid quick dividends, and the improvement in Goody’s play, coupled with an open roster spot, led to another opportunity for Rosen to play in Brooklyn. In his first game back with the Dodgers, Goody foreshadowed the accomplishments that were to come, collecting six hits and three walks in a doubleheader against the Boston Braves.

As the season played on, Goody showed himself to be a player of exceptional abilities. While playing the all-star level defense he was already known for, Goody also became an offensive power, hitting .325. Goody also played every game that season after becoming the regular center fielder, minus September 17, Yom Kippur. All of Goody’s accomplishments of this time added to Goody’s popularity in Brooklyn, as did his birth right, as Brooklyn’s Jewish population eagerly embraced the newest Jewish baseball star. On August 11, the Dodgers fans showed their appreciation of Goody by having a joint Goody Rosen-Marty Marion Day at Ebbets Field. While Honus Wagner presented a scroll and watch to Marion, a fan representative was chosen to present a watch to Goody, while Goody’s teammates presented him with a wealth of cigars.

Goody’s reputation as a fan favorite was solidified by his acts off the field as Rosen and his teammates were active in the Brooklyn community, even at a time before millionaire ballplayers were expected to make at least token goodwill gestures toward the team’s community. One typical example of Rosen’s largesse can be seen in his visiting an orphanage when Goody, at the behest of the orphanage’s head, said that “if someone will donate $100, I’ll tell a story in Jewish.” Getting the requested donation, Goody told a tale in Yiddish to the crowd, and then offered a financial donation of his own.

Goody’s statistics at the end of the 1945 season, even given a loss of nine games to injury, were nothing less than fantastic:

Avg. Hits Runs 2B 3B HR RBI BB SO OBP SLG OPS+

.325 197 126 24 11 12 75 50 36 .379 .460 134

For his efforts, The Sporting News selected Goody for the twenty-first annual National League All-Star team, chosen at the end of the year, as the war had led to the cancellation of the mid-season game. Goody’s season, though often underappreciated, was clearly strong enough to put him ahead of not just teammate Fred “Dixie” Walker (whom he beat by only two votes, 58-56), as well as baseball luminaries Hank Greenberg, Mel Ott, and Charlie Keller, and fellow Canadian Jeff Heath.

While Goody’s season was appreciated (though perhaps not fully) in 1945, it is almost totally forgotten outside of Canada today, despite the fact that it may have, in fact, been the best season in the National League in 1945. It can be taken for granted that Goody was the best defensive outfielder on his team, as he was the National League’s best defensive outfielder up to 1940 and his fielding percentage (.015 above the league average) and his range factor (an amazing 0.50 above the league average) in center field indicate that his defensive abilities did not diminish.

Not only was Goody the most valuable defensive player on the Dodgers, he was the most valuable offensive player on the team, too. Goody Rosen’s offensive contributions were, and continue to be, largely underappreciated. The teammate Goody finished behind in MVP voting, Dixie Walker (they finished 9th and 10th, respectively), produced 25.7 offensive win shares over the course of 153 games, while Goody, despite missing 13 games due to injuries, produced 27.3 offensive win shares. To put this in perspective, Derek Jeter, in his MVP-level 2006 season, produced 28.0 offensive win shares in nine more games and forty-two more plate appearances.

Furthermore, the 1945 Dodgers were one of the National League’s most surprising teams. Not expected to be much of a factor in the pennant race, the Dodgers finished 87-76, leading to a third-place finish in the National League. Having the third worst ERA in the NL, the Dodgers’ successes were clearly a product of their offense, featuring the highest runs per game average (5.13/game) of any team during the World War Two era, clearly outstripping the second-best offense in the majors (4.88/game for the Cardinals).

Given that Goody was the offensive leader of the Brooklyn offensive juggernaut, one would expect his numbers to look more special than they do. Upon closer investigation, however, it becomes clear that Goody’s 1945 season, featuring at least 197 hits, 126 runs, 75 runs batted in, and 11 triples in only 145 games, was a rarity. Throughout the entire twentieth century, only four other players were able to put up the offensive numbers Goody did in as few as 145 games:

Nap Lajoie, 1901

George Sisler, 1922

Al Simmons, 1930

Joe DiMaggio, 1936

Goody’s 1945 season puts him in exceptional company, as Rosen was the last player to reach these levels and is the only one not currently in the Hall of Fame.

In 1946, with outfielders Pete Reiser, Dixie Walker, and Carl Furillo on the club, the Dodgers decided to move Goody only three games into the season. The trade, which involved Rosen and first baseman Jack Graham being sent to the Giants in exchange for $25,000, was executed on April 27, 1946. Though the move was clearly not based on merit (as Goody was arguably the team’s most talented outfielder), it is not altogether clear whether Goody’s unceremonious trade was an economic move or a personal one. In 1993, forty-seven years after the fact, Goody hinted that the move may have been, to some extent, personal:

In those days, money wasn’t easy. After my big season in 1945, Mr. Rickey called me down to his office. He asked how much I expected in my 1946 contract. I told him I expected three times as much as I had been getting.’ All he said was ‘I’m not going to argue with you, but I’ll trade you the first chance I get.’ In spring training, you’d have thought I was a rookie, the way they treated me. Then the season gets under way. We’ve got two games this day with the Giants at the Polo Grounds. I’m on the subway, headed for the park, and I’m readin’ the old New York Mirror. Sports section always starts on the back page. Right across the top it says I’ve been traded to the Giants. Now, that’s the first I know about it.

Oddly, the acquisition of Goody by the Giants may have also had more to do with Goody the person, rather than Goody the ballplayer, as the 1946 New York Giants, trying to capitalize on New York’s vibrant Jewish population, had been collecting talented Jewish baseballers. On the 27th of April, Goody became the fifth Jew on the Giants roster, joining Morrie Arnovich, Harry Feldman, Mike Schemer, and star outfielder Sid Gordon.

Goody’s enormous, though temporary, success on the Giants was likely a surprise to everyone other than Goody himself. In his first day playing for the Giants, Goody collected five hits at the Polo Grounds over the course of a doubleheader. Building on his stellar 1945 season, Goody remained an effective player.

Rosen was also nothing less than poisonous to the Dodgers, for whom he surely felt no little antipathy. One of the reasons for Goody’s effectiveness against the Dodgers might be the open hostility shown to him by his former team. According to Rosen, Dodgers manager Leo Durocher would yell for his pitchers to ‘stick it in his ear’ whenever Goody came to bat, due to held over hostility Durocher felt from Goody’s time in Brooklyn. In response, Goody did what he could to ruin the Dodgers’ season. On July 5, Goody earned another footnote in history by driving home the winning run in the Giants’ 7-6 win over the Dodgers the same night Durocher famously said, in response to questions about Giants manager Mel Ott, that “nice guys finish last.” On August 31, Goody again frustrated his former team, causing a fight between the two clubs after sliding spikes-first into Eddie Stanky during a 2-1 Giants victory.

Rosen’s success against the Dodgers had profound effects on the Giants at the time and up until the current day. On May 3, 1946, New York newspapers began reporting that Branch Rickey was receiving “heavy fan panning” in Brooklyn for trading Goody Rosen, especially considering Rosen’s success against the Dodgers. In 1955, the Toronto Star reported that the Rosen trade was primarily responsible for ending all trades between the Giants and Dodgers as, in the nine years following the trade, the two teams had yet to deal again.

As late as August 10, 2007, a trade of utility player Mark Sweeney from the San Francisco Giants to the Los Angeles Dodgers led to Buster Olney of ESPN.com to comment on the hesitation of the Giants and Dodgers to engage in trades. At the time of the Sweeney deal, the two teams had not engaged in a trade for more than twenty years, the Sweeney deal only being plausible due to Ned Colletti, the General manager of the Dodgers, being the former assistant general manager under Giants GM Brian Sabean. The fact that Goody’s success against the Dodgers in 1946 led to a breakdown in trades between the Dodgers and Giants for the next six decades delighted Goody up until his death in 1994, and it would ultimately be one of Goody’s most lasting legacies.

Rosen’s success with the Giants, however significant, was also short lived, as he ran into the base of a fence while chasing a ball hit by Frank Gustine on May 8, resulting in his being sidelined until May 30 and injured for much longer. Goody later revealed that his injury was a severe sprain of the outer clavicle which prevented him from totally raising his arm for five years. Unfortunately, Goody was rushed back from injury by manager Ott, which only exacerbated the extent of the injury. Goody would later recall that “Ott came to me and asked when I would be ready to get back into the lineup. I told him I could hardly comb my hair, the shoulder was stiff, and he said: ‘Well, the front office is beginning to holler. You’d better get back anyway.’” Goody did, indeed, rush back to action and, having not recovered properly from his injury, was released at the end of the season. By 1947, Goody’s professional career was all but over.

In 1947, Goody made a final effort to continue his professional career, signing on with his hometown team, the Toronto Maple Leafs, a rival of his former team, the Montreal Royals. By all accounts, Goody’s experience with the Leafs was unexceptional. Compiling a .274 batting average, seven home runs, and 58 runs batted in, the season was a clear disappointment for both the former all-star and his hometown team. By the 26th of February, 1948, Goody’s tenure with the Toronto Maple Leafs officially ended, thereby ending Goody’s professional career itself.

It would be wrongheaded to suggest that Goody Rosen’s baseball career ended in 1947, as the end of his professional career actually began a sort of renaissance in his playing career. After Goody’s release from the Leafs in 1948, offers from non-professional teams for Goody’s services came fast and furious. Rosen began his association with the Toronto Beaches Fastball League, coached the Ontario All-Stars in a game against the Toronto Maple Leafs, and played on the Daltons of the Kiwanis-YMCA Senior League as well as the Canadian National Softball Team. On the latter team, Goody was so successful at the World’s men’s tournament in Lubbock, Texas, that he was selected as an All-World NSC outfielder at the tournament’s conclusion.

Finding continued success and regional fame in softball and the Beaches Fastball League (in which he played for three different teams), Goody was given the opportunity to play semi-pro ball in 1950. Owner Gus Murray of the Intercounty Baseball League’s Galt Terriers hired Rosen in August. Murray, an owner of a Guelph wallpaper store and team owner in the mold of Bill Veeck (one team promotion included on-field cake baking demonstrations), needed stars and, in Goody, he found a player whom he thought would draw crowds to Terrier games. Goody did, indeed, play star-level ball, hitting well over .300 in the regular season and nearly .600 in the playoffs. That success, however, did not offset the price of Goody’s services, and Goody retired from baseball for good after the 1950 season.

Though Goody would keep playing amateur baseball after 1950, his attentions were now focused almost wholly on business considerations that could provide a stable family income. Goody had his first attempt at a career alternative to baseball when he opened up the Dunaway restaurant in Toronto in January, 1947. This business failed, but Rosen did end up having a successful business career after his final retirement in 1951. On April 17, 1951, Rosen was appointed a member of the John Labatt Limited Toronto Sales Staff, a spot that capitalized on Rosen’s local celebrity in Toronto. Goody also worked a variety of other jobs in Toronto, including an extended stay with Biltrite Rubber.

In 1984, Goody, almost forty years removed from his last pro baseball game and now a successful business executive in Toronto, was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame. This was the fitting end to the career of a player who, in an April 8, 1994, Toronto Star article, was deemed one of Toronto’s “best kept baseball legends.” For the next ten years, Rosen served as an elder statesman of Canadian baseball, as well as an inspiration for aspiring Torontonian and Jewish ballplayers. So firmly entrenched was Rosen in Toronto’s municipal celebrity culture, in fact, that he received and answered approximately 2,000 pieces of fan mail annually up until his death. On April 6, 1994, Goody died at Sunnybrook hospital in uptown Toronto, due to a case of pneumonia, leaving behind his wife of fifty years, Mildred Rothberg, as well as his son and daughter-in-law Jack and Sandi Rosen.

Sources

Boxerman, Burton A. Jews and Baseball: Volume I: Entering the American Mainstream, 1871-1948. New York: McFarland & Company, 2006.

Cashion, Art. “Goody Rosen, 1940’s ML Baseball & Softball Player.” I.S.C. From The Ballpark. November 3, 2007.

http://www.iscfastpitch.com/webstartme/grumble/grum137.htm.

Dorward, Jane. “Review: Terrier Town ’49.” Nine: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture 13, Vol. 2 (2005): 157-158.

Eisen, George and David K. Wiggens, eds. Ethnicity and Sport in North American History and Culture. New York: Praeger Paperback, 1995.

Gewecke, Cliff. Day by Day In Dodgers History. New York: Leisure Press, 1984.

Horvitz, Peter S., and Joachim Horvitz. The Big Book of Jewish Baseball. New York:

S.P.I. Books, 2001.

Levine, Peter. Ellis Island to Ebbets Field: Sport and the American Jewish Experience. New York: Oxford University Press, USA, 1992.

Levitt, Cyril, and William Shaffir. The Riot at Christie Pits. Toronto: Lester & Orphen Dennys, 1987.

Lynn, Erwin. The Jewish Baseball Hall of Fame: A Who’s Who of Baseball Stars. New York: Shapolsky Publishers, Inc, 1986.

Olney, Buster. “Some Division Deals Make Sense.” Buster Olney Blog. August 10, 2007. ESPN.com Insider; http://tinyurl.com/yolld3.

Ribalow, Harold U. Jewish Baseball Stars. New York: Hippocrene Books, 1984.

Riess, Steven A. Sports and the American Jew. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 1998.

Rutkoff, Peter M. and Alvin L. Hall, eds. Cooperstown Symposium on Baseball and the American Culture. New York: Mecklermedia, 1991.

Smith, Myron J.. The Baseball Bibliography. Jeferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2005.

Speisman, Stephen A. Jews of Toronto: A History to 1937. New York: McClelland & Stewart, 1987.

Spink, J.G. Taylor, ed. 1946 Baseball Guide and Record Book. St. Louis: Charles C. Spink & Son, 1946.

Thorn, John and Pete Palmer. Total Baseball. New York: Viking Press, 1995.

Baseball Cube website. http://www.thebaseballcube.com/

Baseball-Reference website. http://www.baseball-reference.com/

Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame website. http://www.baseballhalloffame.ca/

Goodwin Rosen, #76. Gum Inc., 1939.

“Goody Rosen; Baseball Player, 81.” New York Times, April 8, 1994. http://tinyurl.com/25awv3

Pages Of The Past, Toronto Star archives. http://pagesofthepast.ca/

Retrosheet website. http://www.retrosheet.org/

Full Name

Goodwin George Rosen

Born

August 28, 1912 at Toronto, ON (CAN)

Died

April 6, 1994 at Toronto, ON (CAN)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.