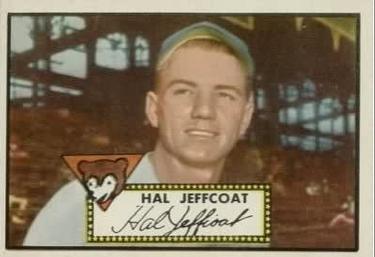

Hal Jeffcoat

When he took the mound on April 7, 1954, Chicago Cubs outfielder Hal Jeffcoat hadn’t pitched professionally since being hit hard in five games in the low minors eight years earlier. Yet, as spring training was ending, he held the Baltimore Orioles to two bloop singles and just one walk over five innings.1

When he took the mound on April 7, 1954, Chicago Cubs outfielder Hal Jeffcoat hadn’t pitched professionally since being hit hard in five games in the low minors eight years earlier. Yet, as spring training was ending, he held the Baltimore Orioles to two bloop singles and just one walk over five innings.1

This unexpected performance by the six-year major-league veteran “electrified his teammates,” Edward Prell wrote in the Chicago Tribune. They mobbed the 29-year-old Jeffcoat on the field, slapping him on the back after he retired the final batter in the ninth.2

“It was a great feeling to have everyone shake my hand,” said Jeffcoat, who called it the highlight of his years with the Cubs.3 Thus began the sudden transformation at the major-league level of a speedy, strong-armed, outfielder into a solid right-handed pitcher who would spend his last six seasons on the mound.

Jeffcoat made his regular-season pitching debut in the Cubs’ opener on April 16. So unfamiliar was he with his new position that he took several strides toward the outfield on the first fly ball hit off him before he realized where he was.4 Still, he acquitted himself well, with two scoreless innings in relief, keeping the game close. The rest of the Chicago bullpen fared less well, as the Cincinnati Redlegs pounded the Cubs, 11-5, before just 17,271 fans at a rainy Wrigley Field.5 He became a reliable reliever for two seasons and, after being traded to the Redlegs, joined the Cincinnati rotation as a full-time starter in 1957. He finished his career back in the bullpen with the 1959 St. Louis Cardinals and a year at Triple A before hanging up his spikes.

Harold Bentley Jeffcoat was born in West Columbia, South Carolina, on September 6, 1924, one of five children – four boys and a girl – of George McCoy and Alma (Bundrick) Jeffcoat. The Jeffcoat side of the family was of English descent. Hal’s mother was killed in a traffic accident when he was child, and Hal and his sister, Nellie, spent two years in a North Carolina orphanage before they returned to West Columbia to live with their brother George, nearly 11 years Hal’s senior. His father, who worked as a security guard at the mills across the river in Columbia, died in 1944.6

“Everybody played baseball back then,” said retired Navy Capt. John P. Jeffcoat, one of Hal’s three sons, of his father’s early years.7 Brother George was a heralded pitching prospect by the time Hal was old enough to play. George Jeffcoat went on to pitch in National League for the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves. Their father taught all four of sons to play as soon as they reached age 5.

The three older brothers, all pitchers, played together for the Columbia Mills semipro team near their home, as did Hal when he turned 14. Hal’s oldest brother, Charlie, a left-hander, signed with the New York Yankees in 1926 and pitched in the minors, as did brother Bill, who was signed by Bill Terry of the New York Giants, who mistakenly thought he was signing George.8

Hal Jeffcoat graduated from Brookland-Cayce High School in West Columbia in 1940. He once struck out 18 batters in a seven-inning high-school game.9 He was recruited by an uncle to play for an American Legion junior team in Montgomery County, North Carolina. To qualify, he had to enroll in the local Troy High School, where he played a season of football and baseball. This apparently was a common practice at the time, with local families providing housing for athletes brought in from elsewhere in the region.10

After graduation, Hal went to work with his uncle Charlie building World War II Victory Ships at the Jacksonville, Florida, shipyards. On June 4, 1943, the 18-year-old Jeffcoat entered the Army at Fort Jackson, South Carolina. He became a paratrooper with the 21st Engineer Regiment, 101st Airborne Division.11 By the time of his discharge, he had attained the rank of staff sergeant. He first served in France and then was moved into Italy, where he was wounded.12

While recuperating in Naples, Jeffcoat was smitten by a member of the Women’s Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC), Valma Viola Ala, the daughter of Finnish immigrants. They kept in touch. When Jeffcoat was discharged, he sent a telegram asking her to meet him at the station in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where she lived. When he arrived, neither having seen the other out of uniform, they passed five times on the station platform before they recognized each other.13

The couple married on January 14, 1946, in Lanesville, Massachusetts, Valma’s hometown. They lived there and in Gloucester in the offseason, where Jeffcoat worked at various times as a carpenter and as a stone mason and even delivered mail during the first few years of his major-league career.14 Harold G. Jeffcoat, the first of their three sons, was born in 1947 in Nashville, Tennessee, while his father was playing there.

Jeffcoat made 13 jumps as a paratrooper and earned a Purple Heart for a wound. His son John said his father never spoke much about his war experience, although it came up once when the sons were talking about fear. Jeffcoat told them that he had been under sniper fire and that he took cover behind a tree. With snipers watching for anything that moved, Jeffcoat remained there for hours until darkness fell. “You figure out what to do,” he told his boys.15

George Jeffcoat had pitched several seasons for the Double-A Nashville Volunteers in the Southern Association. He sent a telegram to Vols manager Larry Gilbert, who also owned the team, saying that he had a kid brother who “would be a great pitcher when he got out of the army.” Gilbert, who eventually signed Hal for $2,500,16 assumed that the younger Jeffcoat was what his brother said he was when the Army veteran reported to the Vols camp in Macon, Georgia, in the spring of 1946.

“Skip, I’m not a pitcher,” Hal told Gilbert. “I’m a center fielder.”17 Although he was sent down to play for Class B Shelby in North Carolina for most of 1946, Jeffcoat backed up his claim to be a position player with a 35-game hitting streak and a .346 batting average in 1947. Always fast, Jeffcoat had 36 doubles and 13 triples, while knocking in 118 runs and excelling in center field.

Following his success at Nashville, Jeffcoat was sold to the Cubs on January 16, 1948, for two Double-A prospects and an undisclosed amount of cash.18 Nashville was an independent minor-league team, but in practice acted as Chicago’s Double-A affiliate, with the Cubs having first rights to its best players.

After making the Cubs out of spring training, Jeffcoat got off to a hot start in ’48. In early June he was hitting .323, good for eighth in the league. He also was impressing fans with his speed and arm in the outfield.19 His 11 assists from center field led the league. It was the first of four seasons in which he had 11 or more, topping out at 16 assists in 1952.

The idea of pitching must never have been too far from the minds of those who watched Jeffcoat throw, even though he hadn’t pitched at all in 1947, or for the Cubs in the spring of ’48. “Hal Jeffcoat … is proving it was no mistake to make him over from a pitcher to an outfielder,” Jack Hand of the Associated Press wrote in late April 1948.

On August 28, 1948, Jeffcoat crashed into the center-field wall at Wrigley Field chasing a fly ball. He was knocked unconscious briefly and was taken to a hospital. At the same hospital hours earlier, his wife had given birth to their second son, John. While he was being examined, Jeffcoat got his first look at the newborn.20

Jeffcoat’s hustle and sparkling play in center made him an immediate fan favorite in Chicago and garnered him substantial support for the National League All-Star squad. At season’s end, he was selected as the center fielder on The Sporting News rookie all-star team.21

After his .279 performance in 512 plate appearances as a rookie, Jeffcoat went to spring training in 1949 penciled in as a regular outfielder for the Cubs. A victim of the sophomore jinx, he hit .156 in April and was optioned to Triple-A Los Angeles on June 6, but ended up being recalled before playing a game there.22

“He went after so many high outside pitches that manager Charlie Grimm benched him,” wrote Raymond Johnson of The Tennessean in Nashville.23 Jeffcoat’s batting slump limited him to 388 plate appearances in 108 games, with a negative 0.1 wins above replacement (a retrospective statistic that didn’t exist when he played). He improved, however, after his recall and hit .275 the final two months of the season.

Frankie Frisch, who had replaced Grimm in June, said after the season that he wanted Jeffcoat to work on his baserunning. “He’s got speed,” Frisch told Cubs beat writer Edgar Munzel. “He should be one of the league’s best base stealers.”24 In fact, Jeffcoat’s 12 steals had placed him third in the league in ’49.

Hoping to bounce back in 1950, Jeffcoat instead broke his collarbone diving for a ball on May 14, an injury that sidelined him until July 16. “I was in combat two and half years as a paratrooper. I made 13 jumps out of an airplane” without getting hurt, he said. “Now I get busted up for two months chasing a little white ball.”25

The injury and reduced playing time contributed to another weak year at bat, rekindling talk of Jeffcoat’s pitching prospects. “Frisch is toying with the idea of converting Jeffcoat into a hurler. He had two reasons: 1. Jeff isn’t hitting … 2. The Cubs are in dire need of hurlers,” wrote Raymond Johnson in the August 1, 1950, Tennessean.26

In the spring of 1951, team owner P.K. Wrigley had the Cubs train on Catalina Island, off the coast of Southern California. While there, some of the players participated in a series of rodeo-style events, with Jeffcoat winning the overall championship.27 Whether Catalina Island had any effect isn’t clear, but Jeffcoat had his best year at the plate since his rookie season. He was limited to 299 plate appearances, but hit .273. His 20 doubles – 26 of his 76 hits were for extra bases – helped him post a career-best .718 OPS (on-base-plus-slugging, a retrospective statistic).

During 1951, Jeffcoat’s roommate on the road was a 6-foot-5 first baseman named Chuck Connors, who gave up baseball after another season to try acting. He later became a star in the TV western series The Rifleman, which ran from 1958 to 1963. “Every time it was on, John Jeffcoat recalled, his dad would say, “There’s my roomie.”28

Encouraged by Cubs coach Spud Davis, a longtime catcher, Jeffcoat often threw with him in sideline sessions, working on various pitches and his control of them in years before his switch to the mound. He became one of the Cubs players’ favorites to throw batting practice, but once Phil Cavarretta replaced Frisch as manager at midseason in ’51, the idea of trying Jeffcoat as a pitcher was shelved.29

Caverretta, with slow-footed veterans playing left and right, was enamored of Jeffcoat’s defense. But as the ’52 season began with Hal getting just two hits in his first 32 at-bats, the manager was forced to bench him. He ended the year with a career-worst .219 batting average.

“I still haven’t given up” on him, the manager said. “Jeffcoat’s hustle, speed, and determination make up for a lot of other shortcomings.” Hal also had the backing of Wid Matthews, the Cubs’ general manager (officially the director of player personnel), who praised Jeffcoat in a column by J.G. Taylor Spink of The Sporting News.

“Hal Jeffcoat has unlimited potential,” Matthews said. “I had a chance to deal Jeffcoat but I didn’t. To me, he’s the greatest center fielder in the league and a tremendous asset regardless of what he hits.”30

Although his on-base percentage jumped 55 points to .314 in ’53, Jeffcoat was most often used as a defensive replacement, getting to the plate just 206 times in 106 games. Clearly, his major-league career was on shaky ground headed into the 1954 season.

Cubs coach Bob Scheffing was an advocate of trying out Jeffcoat on the mound. He would catch him as he warmed up to throw batting practice. “Scheffing … liked what I was throwing. The pitch was a natural sinker and he asked me if I could throw it all the time,” Jeffcoat told the Cincinnati Enquirer in 1958. “I told him I thought so.”31

Scheffing finally managed to get Cavarretta to agree to let Hal, who was still working out as an outfielder, pitch in a spring-training game. Before that happened, Caverretta was fired. His replacement, Stan Hack, needed little convincing after Scheffing got him to watch Jeffcoat throw a bullpen session.

“He showed me more stuff” than most of the other pitchers had, Hack said, “with his fastball, two varieties of curveball and a screwball.”32 The stage was set for Jeffcoat’s debut in the exhibition game played in New Orleans on April 7. He had to borrow a glove and use his regular spikes when he entered the game against the Orioles.

“They’re gonna have to buy me a new pair of shoes, complete with a leather toe plate,” Jeffcoat said after his five shutout innings. “I’ve been trying for three years to get a chance to pitch in a game for the Cubs.”33 He mentioned the encouragement of Davis, Scheffing, and Roy Johnson. “The coaches talked to me many times about making the switch.”34

His regular-season debut on April 16 at Wrigley was no walk in the park. The 5-foot-10 righty retired Reds left-handed sluggers Gus Bell and Ted Kluszewski during his two innings.

Hack was duly impressed. “I’m not afraid to relieve with him when the chips are down. He’s got plenty of moxie and he can get the ball over the plate,” Hack said. “Later on, I’ll give him a starting shot.”

Jeffcoat’s 1954 performance was uneven. He did get three starts that season and completed one of them. He notched seven saves, but he walked 58 batters in 104 innings and his earned-run average was 5.19. He went to Puerto Rico that fall to pitch in the winter league – on a team that featured Willie Mays – to refine his mound skills. It paid off. In 1955 he blossomed into one of the league’s top relievers. He pitched in 50 games – 49 in relief – and lowered his ERA to 2.95. His walks were still too high – although a league-leading 12 of them were intentional – but he rarely yielded the long ball – just 0.6 homers per 9 innings.

That fall the Cubs traded the 31-year-old Jeffcoat to Cincinnati for 25-year-old backup catcher Hobie Landrith. At first Jeffcoat resisted the move, saying he planned to retire and concentrate on selling insurance. Redlegs manager Birdie Tebbetts persuaded Jeffcoat to keep pitching and sell his policies in the offseason.35

He performed well in a swing role for the Redlegs. He went 7-1 and started 12 games in the season’s second half. Overall, he was 8-2, with two complete games and two saves. More importantly, his walks per nine innings were way down.

On June 23, 1956, against the Dodgers, Jeffcoat threw a pitch that hit Don Zimmer in the face, breaking his cheekbone and causing a detached retina. Zimmer missed the rest of the season and was never again the same player. Sportswriter and ESPN commentator Tim Kurkjian in a column shortly after Zimmer’s death in 2014 said Zimmer thought that Jeffcoat had thrown at him and was bitter that Jeffcoat had never called him after his injury.36

In May 1957, however, Zimmer was quoted by Murray Robinson in The Sporting News as saying that he didn’t see the pitch that hit him “and it was an accident.”37 John Jeffcoat said his father told his mother on several occasions that that the pitch simply got away and that he did not mean to hit Zimmer.

On the final day of the ’56 season, September 30, Jeffcoat faced Monte Irvin in what was the future Hall of Famer’s final major-league plate appearance. In relief and trying to protect a 4-0 lead, Jeffcoat threw a wild pitch that allowed a run to score before walking Irvin. The Redlegs held on to win, 4-2.38

Jeffcoat was happy with his steady improvement. “Adding a sidearm curve helped me fool the hitters, and I improved … by getting better control,” he said after season. “I won’t have to feel my way next year … as I did the first half” of ’56.39

Tebbetts obviously liked Jeffcoat. “There isn’t anything he can’t do well,” the manager said as the 1957 season began. “He’s the best bet on our club now to win 20 games.” The respect was mutual. “I learned from Birdie to take things as they come,” Jeffcoat said. “I used to get mad. He taught me that doesn’t pay off in the win column.”

In the starting rotation for a solid Redlegs team in 1957, Jeffcoat was a 1-0 loser to the Braves in the season’s second game. He shut out the Braves on three hits through the first five innings before surrendering a homer to Hank Aaron in the sixth. But by the All-Star break, he had eight wins. Jeffcoat tossed his only complete-game shutout against the defending champion Dodgers at Ebbets Field on June 9, winning 3-0 on a six-hitter in the second game of a twin bill. A month earlier, two unearned runs had denied him a shutout on the same field, but he did win, 4-2.

Although he stayed in the rotation all season, his performance indicated that the workload tired him in the second half. So in ’58, Tebbetts used him exclusively in relief, a practice Jimmy Dykes continued after replacing Tebbetts 104 games into the season. Jeffcoat responded with nine saves in 49 games and a career-best 1.360 WHIP (walks and hits per nine innings).

Jeffcoat’s 1959 season started well enough. He had a 3.32 ERA in 17 relief outings and a save when he was traded to the Cardinals for 29-year-old Jim Brosnan, a deal that worked out much better for the Reds (the team went back to being “the Reds” in ’58). Although Jeffcoat thought pitching in the more spacious Busch Stadium would help him,40 it didn’t turn out that way. In just 11 games, his ERA was 9.17. The Cards released him in October.

At 35, he gave it one more try with Seattle, the Reds’ Triple-A affiliate, in 1960, but the results weren’t there. His ERA was 6.38 after 17 games. He was out of baseball in 1961, but took over as manager of the Palatka Cubs in the Florida State League in 1962. Headed for a last-place finish and missing his growing sons, he left before the season ended, replaced by Rube Walker.

Jeffcoat returned to his new home in Tampa and took a job with the Continental Can Co., where he stayed until he reached retirement more than 20 years later. “Dad had to provide for the family,” son John said. “He earned a pension [from his playing career], but in those days, you couldn’t collect until you were 45.”41

Jeffcoat watched his oldest son, Harold “Bucky” Jeffcoat, develop into a pitching prospect for the San Francisco Giants, making it to spring training with them after a standout year at Fresno in 1966. But the younger Jeffcoat eventually chose a different career, earning a doctorate and becoming the president of two universities.42

When the majors expanded to Tampa Bay, Jeffcoat became a fan, son John said, although he didn’t attend many games. He was active in his church – Holy Trinity Lutheran – and held a number of lay-ministry positions for more than 50 years. His brother George, who died in 1978, had become a minister after his playing days.

John Jeffcoat said he was proud that Ernie Banks, with whom his father played when Mr. Cub was rookie, recalled his dad as “a fine gentleman” on hearing of Hal Jeffcoat’s death on August 30, 2007.43 In 1998 Frank Robinson, who in his rookie season also played with Jeffcoat, said the former outfielder took 15 to 20 minutes every day helping Robinson learn how to play the tricky left-field Terrace in Cincinnati’s Crosley Field.

Jeffcoat’s name came up on August 18, 2016, when the Giants’ Madison Bumgarner duplicated a feat that only Jeffcoat had managed previously in a post-1900 game. Both pitchers had given up grand slams in the top of an inning, and then hit go-ahead homers themselves in the bottom of the inning. Jeffcoat did it on May 26, 1957, yielding his slam to Stan Musial and hitting his homer off Herm Wehmeier. Bumgarner was victimized by the Mets’ Justin Ruggiano, and then hit his off Jacob deGrom. Both homer-hitting pitchers ended up winning their games.44

Jeffcoat is buried in the Florida National Veterans Cemetery in Sumter County, Florida. He and his wife had been married for 61 years when he died. Valma Jeffcoat died in 2010 and was laid to rest next to her husband.

Notes

1 Edward Prell, “Cubs Win, 2-0; Jeffcoat Hurls 5 Innings,” Chicago Tribune, April 8, 1954: 63.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Edgar Munzel, “Hal Fourth Jeffcoat Brother on Mound,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1954: 3.

5 Prell, “Rain, Hit Showers Spoil Cub Opener, 11-5,” Chicago Tribune, April 16, 1954: 39.

6 Email from Harold G. Jeffcoat, February 21, 2017; obituary, St. Petersburg Times, October 1, 2007, accessed online February 16, 2017; telephone conversation with John P. Jeffcoat, February 16, 2017.

7 Ibid.

8 Munzel, “Hal Fourth Jeffcoat Brother.”

9 Prell, “Cubs Win.”

10 Ibid..; John Galloway, Montgomery (North Carolina) Herald, posted August 9, 2002; montgomeryherald.com/sports/article_58986c26-e0d6-11e1-a667.

11 Gary Bedingfield’s Baseball in Wartime, baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/jeffcoat_hal.htm.

12 Email from Harold Jeffcoat; conversation with John Jeffcoat.

13 Ibid.

1418 Ibid.

15 Ibid.

16 Associated Press, “2 of Cubs’ Kiddie Corps Making Grade,” Des Moines Register, May 6, 1948: 14.

17 Raymond Johnson, “One Man’s Opinion” Tennessean (Nashville), June 15, 1947: 45.

18 Unbylined news brief, “Cubs Purchase Hal Jeffcoat From Nashville,” The Tennessean, January 17, 1948: 7.

19 Associated Press, “2 of Cubs.”

20 Conversation with John Jeffcoat.

21 Edgar Munzel, “Early Foot Cubs Find Center Field an Achilles Heel,” The Sporting News, May 5, 1952: 15; Edgar G. Brands, “Second-Division Players Top Rookie Team,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1948.

22 Associated Press, “Cubs Option Hal Jeffcoat to Angels,” Bloomington (Illinois) Pantagraph, June 7, 1949: 13; Associated Press, “Cubs Option Burgess, Recall Hal Jeffcoat,” Pantagraph, June 16, 194: 17.

23 Johnson, “One Man’s Opinion.”

24 Edgar Munzel, “Petunia Man Frisch Plans Strawberries,” The Sporting News, November 23, 1949: 13.

25 Hal Jeffcoat biography, Baseball Historian, baseballhistorian.com/players.cfm?lookieplayer+jeffcha01.

26 Johnson, “One Man’s Opinion.”

27 Edward Burns, “Enchanting Catalina, Isle of Fantastic Confusion and Cubs,” Chicago Tribune, March 25, 1951: 33.

28 Conversation with John Jeffcoat; Prell, “Cubs Win.”

29 Prell, “Cubs Win”; Associated Press, “Jeffcoat Turns Pitcher,” Decatur (Illinois) Daily Review, April 8, 1954: 45.

30 J.G. Taylor Spinks, “Looping the Loops: Cubs Upsurge Tribute to Wid,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1952: 4.

31 Bill Ford, “Bill Ford’s Notes,” Cincinnati, Enquirer, June 1, 1958: 59.

32 Munzel, “Hal Fourth Jeffcoat Brother.”

33 Ibid.

34 Associated Press, “Jeffcoat Turns Pitcher.”

35 Tom Swope, “Hal Jeffcoat Balks at Trade, Then Decides to Join Reds,” The Sporting News, December 7, 1955: 21.

36 Tim Kurkjian, “Don Zimmer Simply Loved Baseball,” espn.com/mlb/story/_/id/11035595/don-zimmer-leaves-legacy-devotion-baseball-mlb, June 5, 2014.

37 Murray Robinson, “Don Zimmer, Frequent Target, Defends ‘Brushoff’ Pitches,“ The Sporting News, May 29, 1957: 11.

38 Jim Baker, “Exiting Stage Left,” baseballprospectus.com/artcle.php?articleID+7387, posted July 7, 2008.

39 Tom Swope, “Three-Year Mound Rise Under Tebbetts Buoys Reds’ Hopes,” The Sporting News, December 5, 1956: 11.

40 Ralph Ray, “Cards Hunt Aces in Rapid Shuffle by Dealer Devine,” The Sporting News, June 17, 1959: 14:

41 Conversation with John Jeffcoat

42 Denny Paterson, The Decaturian, student news site at Millikin (Illinois) University, February 13, 2013, http://decaturian.com/news/2013/02/13/president-harold-jeffcoat-retires-2/.

43 Ibid.

44 Michael Wagaman (Associated Press), “Giants Finally Get Some Offense in 10-7 Win Over Mets,” apnews.com/7f5582a0e7534c6a88ff5e552cec64aa, August 18, 2016.

Full Name

Harold Bentley Jeffcoat

Born

September 6, 1924 at West Columbia, SC (USA)

Died

August 30, 2007 at Tampa, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.