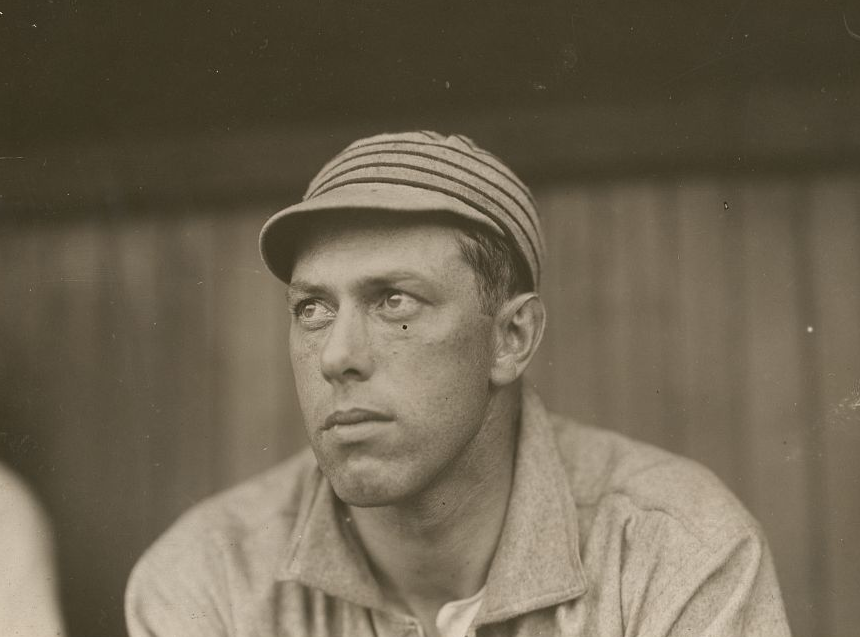

Jack Coombs

For one magnificent season, “Colby Jack” Coombs was the equal of any pitcher of the Deadball Era, Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson and Grover Cleveland Alexander included. Armed with an above average fastball and a devastating drop curve, Coombs had one of the most dominant pitching seasons in baseball history in 1910, rolling up a 31-9 record to propel Connie Mack‘s Philadelphia Athletics to the American League pennant by 14½ games. He put together a remarkable 1.30 ERA in 353 innings pitched and completed 35 of the 3 games he started. In addition, Coombs threw 13 shutouts, an American League record that will stand for the ages. In 11 other games he held the opposition to one run.

For one magnificent season, “Colby Jack” Coombs was the equal of any pitcher of the Deadball Era, Christy Mathewson, Walter Johnson and Grover Cleveland Alexander included. Armed with an above average fastball and a devastating drop curve, Coombs had one of the most dominant pitching seasons in baseball history in 1910, rolling up a 31-9 record to propel Connie Mack‘s Philadelphia Athletics to the American League pennant by 14½ games. He put together a remarkable 1.30 ERA in 353 innings pitched and completed 35 of the 3 games he started. In addition, Coombs threw 13 shutouts, an American League record that will stand for the ages. In 11 other games he held the opposition to one run.

For the last half of the 1910 season, Coombs was simply unhittable, all the more remarkable because of his heavy workload. He threw 12 shutouts, pitched 250 innings and won 18 of 19 starts in July, August and September. From September 5 to September 25 he racked up 53 consecutive scoreless innings to set a major league record (broken three years later by Walter Johnson). Jack then topped off his incredible year by pitching three complete game wins against the Chicago Cubs in six days as the Athletics won their first World Championship in five games. He was nearly as good in 1911, leading the A’s to their second straight pennant with a record of 28-12.

John Wesley Coombs was born on November 18, 1882 in Le Grand, Iowa, a tiny farming community some 50 miles northwest of Des Moines. Coombs’ family moved to a farm near Kennebunk in southern Maine when young Jack was about four years old. He attended Freeport High School and a prep school named Colburn Classical Institute in Waterville, Maine, showing pitching prowess and starring in football as well. Entering Colby College in 1902, he starred in baseball, basketball, football and track, serving as captain of the first two. Jack was an outstanding runner in football and the fastest sprinter in New England, running the 100-yard dash in 10.2 seconds. In baseball he pitched and hit Colby to several Maine collegiate championships, playing every position, including catcher in emergencies. He spent his summers playing semi-professional baseball in St. John, New Brunswick (1903), Northampton, Mass. (1904) and Montpelier, Vermont (1905).

An excellent student, the bespectacled Coombs majored in chemistry and had every intention of making that his life’s work. In fact, he had been accepted to MIT for graduate work when Tom Mack, Connie Mack’s brother who lived in Worcester, Mass. and had followed Jack, signed him to a big league contract in December, 1905, with the understanding that Coombs would report to the Athletics after graduation in 1906. As a senior, the 6’0″, 185-pound right-hander led Colby to a 14-3 record, hurling a 1-0 victory over the University of Maine on his own home run. The day after his graduation he defeated traditional rival Bowdoin 6-0 for the Maine championship.

Colby Jack made his major league debut on July 5, 1906 and it was a memorable one, as he pitched a seven-hit shutout to defeat the Washington Senators 3-0. After that impressive debut Coombs had rather indifferent success for July and August and went into a September 1 start against Boston with a 5-7 record. That day’s scheduled doubleheader turned into a single, epic 24-inning contest, in which both rookie starters, Coombs and Boston’s Joe Harris, went the distance. Coombs won the game, striking out 18 and allowing 15 hits in 24 innings. Colby Jack threw two more complete game victories in the next 10 days. Dogged by arm trouble in the final weeks of the season, Coombs nonetheless finished his rookie year with a solid 10-10 record in 173 innings. After a strong start in 1907, Coombs again strained his arm and struggled to a 6-9 record for the second -place Athletics, causing considerable concern that he was a flash in the pan.

A’s outfielder Socks Seybold broke his leg in spring training the next year, prompting Connie Mack to insert the good hitting but still ailing Coombs in right field. Jack, who would bat .235 for his career, started the season like a house afire, hitting over .300. When he slumped to .215, however, he found himself back on the bench, replaced by veteran second baseman Danny Murphy. Still, his hitting record at season’s end was better than the league average.

Back on the mound for the last half of 1908, Coombs posted a 7-5 record and an excellent 2.00 ERA in 153 innings as the Athletics slipped to sixth place. Still not completely healthy, he was 12-11 in 1909 with 18 complete games in 24 starts and an impressive 2.32 ERA as the A’s rebounded and lost the pennant by only 3½ games to the Detroit Tigers. After four years, his won-loss record was an unimpressive 35-35. He began 1910 slowly, getting beaten in succession by the Senators and the Highlanders. Those efforts earned him a demotion from the starting rotation.

Two weeks later Connie Mack inserted Coombs into the ninth inning of a 3-3 tie against Ed Walsh of the White Sox when Eddie Plank was removed for a pinch hitter. For the next three innings Jack held the Pale Hose hitless as the A’s finally pushed across a run in the eleventh to win 4-3. His rediscovery of his overhand curve apparently was the key. As former catcher Malachi Kittridge observed, Coombs’s devastating breaking pitch wasn’t “one of those outdrops, but a ball that comes up to the plate squarely in the center and falls from one to two feet without changing its lateral direction.” His season revived, Coombs found himself starting two to three times a week on the way to his remarkable 31-9 season. On August 4 he again hooked up against Walsh in a sixteen-inning duel that ended in a scoreless tie because of darkness. Coombs considered this the best game he ever pitched. For the afternoon, he struck out 18 and gave up only three hits. On September 25 Colby Jack and Big Ed found themselves in another long duel in the first game of a doubleheader. Again relieving Plank in the ninth, Coombs pitched the final six innings of the 14-inning game, starting the A’s winning rally himself with a hit in the 14th. However, Coombs was spent, and gave up three runs to the Sox in the second inning of the second game, thereby ending his record-setting 53-inning scoreless streak. It was during Coombs’ monumental 1910 year that he earned the sobriquet “Iron Man.” And earn it he did, at one point pitching ten complete games and finishing two others during a 16-day period.

In the World Series against the Cubs, who had swept to the National League pennant by 13 games, Coombs defeated Cub ace Mordecai (Three Fingered) Brown in Game 2, 9-3 in Philadelphia after Chief Bender had won Game One for the A’s. On the train to Chicago the following day reporters asked Connie Mack who would pitch Game 3. When he replied, “Why Coombs will go for us again,” they thought he was spoofing. But sure enough, Jack trotted out for Game 3 with one day’s rest in a sleeper car and defeated the Cubs, 12 to 5 in another complete game performance. After Bender lost Game 4, 4-3, Coombs pitched with two days’ rest, defeating Brown for the second time, this time by a 7-2 score to wrap up the Series for the A’s. All told Coombs had pitched three complete game victories in six days. He even hit .385 in the Series with five hits in 13 times at bat. For the Series, Connie Mack used only two pitchers, Coombs and Bender, leaving such stalwarts as Eddie Plank (sidelined with a sore arm) and Cy Morgan on the bench.

To top off his banner 1910 year, Coombs married the former Mary Elizabeth Russ of Palestine, Texas in November. He met his future bride during a spring training trip in 1907 and fell in love not only with her but with her hometown. For the rest of his life the Coombses maintained a home in Palestine. Jack, even when coaching college baseball at Duke after his retirement as a player, would spend most of the winter in Palestine, hunting, fishing and relaxing. (He lost a finger on his left hand in a 1936 hunting accident when a barrel of his shotgun burst as he fired at a quail.) He eventually acquired extensive land holdings in the area.

The Colby Kohinoor, as Coombs was sometimes called in the press, fell back to earth in 1911, posting a poor 3.53 ERA despite leading the American League with 28 wins. The Athletics won a second consecutive pennant, this time by 13½ games over the Detroit Tigers, and Coombs pitched the pennant-clinching win on September 28. Jack also flexed his muscle at the plate, batting a lusty .319 for the year. He hit two extra-inning home runs, in the fourteenth inning against the Browns on July 17 and in the eleventh on August 29 against Detroit, the last homer ever hit in old Bennett Park. (After the latter homer, however, he fumbled away the game on the mound in the bottom of the 11th.) Among major league pitchers, only Dizzy Dean has tied Coombs’ mark of two extra-inning home runs.

In the World Series against John McGraw‘s New York Giants, Coombs pitched the memorable Game 3 against Christy Mathewson, winning the contest 3-2 in extra innings after Frank Baker had tied the game with a ninth inning home run. Coombs allowed only three hits in his fourth World Series triumph. Following the A’s Game 3 triumph, the Series was beset by a week of rain but Coombs started Game 5 eight days later, hoping to close the Series out for the Athletics. It looked like he would, too, as he came within one out of a 3-1 victory. The Giants, however, rallied to tie the score and send the game into extra innings. It turned out that Coombs had badly strained his groin in the sixth inning, catching his spikes on the mound during a pitch. Twice Connie Mack sent Chief Bender to the mound to see if Coombs could continue and both times he refused to leave the game. In the top of the 10th Jack beat out a bunt hit, his face contorted in pain. With that, Mack put in Amos Strunk as a pinch-runner. The A’s lost in the bottom of the tenth on a Fred Merkle sacrifice fly against Eddie Plank. That evening, Coombs was feverish and bed-ridden.

Coombs still felt the effects of his groin pull in 1912, and after starting opening day, missed the next month of the season. He recovered enough to win 21 games while losing only 10 in 262⅓ innings, about 75 innings fewer than the year before. During spring training in 1913 Jack came down with a high fever in Montgomery, Alabama which initially was diagnosed as ptomaine poisoning and pleurisy. After considerable rest, Coombs started the opening game for the A’s at Boston on April 10. After three hitless innings, he gave way to Bender in the sixth, leading 10-5. Two days later he started again against Boston but left after facing only five batters, giving up two hits, a walk and hitting a batter.

Jack accompanied the team to Washington after the Boston series but he was in so much pain the team sent him home to Philadelphia. There he entered the hospital and by May he was near death from typhoid fever which settled in his spine. In early August, Coombs felt well enough to work out at the ballpark but soon landed back in the hospital for a lengthy convalescence. He endured 17 weeks of bed rest with weights hanging from his head and legs to strengthen his spine. His weight fell from 180 to 126 pounds.

He spent the winter resting in Palestine, but was not ready to resume his career in 1914. He worked out with the team when he felt strong enough and started two late season games as the A’s captured their fourth pennant in five years. After the “Miracle” Braves swept the Athletics in the World Series Connie Mack began to disband his powerhouse team. Mack released Coombs, who signed with the Brooklyn Robins, managed by Wilbert Robinson. At 32, after missing virtually two complete seasons, Colby Jack made a remarkable comeback in 1915, winning 15 and losing 10 with a 2.58 ERA in 195⅔ innings for the third-place Robins. Facing Christy Mathewson for the first time since the 1911 World Series, Coombs twice beat him in head-to-head duels, keeping his perfect record against the Giants legend intact.

Coombs had thrown so many curveballs during his career that, according to F.C. Lane, “his arm is actually shortened by the stiffening of the cords at the elbow.” Despite the heavy workload his right arm had sustained over the years, Coombs remained an effective spot starter for the Dodgers in 1916, as he went 13-8 with a 2.66 ERA to help Brooklyn to its first World Series appearance. Although the Dodgers lost the Series to the Boston Red Sox in five games, Jack started and won Game 3, 4-3 against Carl Mays for Brooklyn’s only victory. It was Coombs’ fifth World Series victory without a loss. Coombs continued his role as a spot starter and reliever for 1917 and 1918 with less success, compiling 7-11 and 8-14 records. He threw his 35th and last big league shutout on August 1, 1918, blanking the Cincinnati Reds 4-0. On August 30, Jack lost to Pol Perritt of the Giants 1-0, allowing the lone run in the ninth inning. The game took but 56 minutes to play. Afterward, Coombs announced his retirement.

The second-division Phillies signed Coombs to manage for 1919 but it was not a happy experience. He resigned on July 8 with an 18-44 record. He served as a coach for Hughie Jennings and the Detroit Tigers in 1920 and even relieved in two games.

Coombs soon found his niche, however, as a college baseball coach, first at Williams (head coach, 1921-1924), then at Princeton (pitching coach, 1925-1928) and finally at Duke for 24 years (head coach, 1929-1952). While at Duke he authored the leading instructional book of its day, Baseball – Individual Play and Team Strategy, published in 1938 by Prentice-Hall. The book went through many editions and was eventually used at 187 colleges and universities and at hundreds of high schools.

At Duke Coombs led the Blue Devils to an overall 382-171 record, winning seven North Carolina state collegiate championships, five Southern Conference championships and earning the title “Mr. College Baseball.” Twenty-one of his players made the major leagues including Billy Werber, Dick Groat, and his nephew, Bobby Coombs. Many more were All-Americans, including Bill W. Werber, Billy Werber’s son.

Werber, who played shortstop for Coombs from 1928-1930, later described Coombs as “a great man and a great coach,” and “the most beloved teacher or coach to ever walk the Duke campus.” He recalled that Jack had a breezy, disarming personality that could win anyone over. Coombs and his wife Mary had no children and would often entertain his student-athletes at their campus apartment. Werber remembers Coombs walking up behind Duke University President William Preston Few, a scholarly, dignified man in a dark suit and felt hat, slapping him on the back in a friendly fashion and saying, “Prexy, we’re having a practice game tomorrow and I’m counting on you to umpire.” “I’ll be there, Jack,” was the reply.

As the Duke coach, Coombs always wore a coat, tie and hat in the dugout and usually a vest irrespective of the heat. He made the team wear large baggy pants in the Deadball Era fashion. Bill W. Werber remembered that Coach Coombs was direct and had a sense of humor. His most common admonition to him in the field was to “get your buttocks down, Werber.” He also told young Bill more than once, “Don’t think Werber. When you do you hurt the team.”

After a forced retirement from Duke in 1952 – university policy mandated retirement at age 70 – Jack and Mary Coombs returned to live in Palestine full-time. Each spring until he died he conducted a free baseball clinic there for high school coaches and players. Coombs enlisted Ira Thomas, his old battery mate from the Athletics, and players he had coached to come in to assist him.

On April 15, 1957 Coombs became ill while running errands in downtown Palestine. He returned home and went into the bedroom to lie down. By the time his wife Mary could summon the family physician, he was dead from a heart attack. He was buried in St. Joseph’s Cemetery in Palestine. The baseball fields at both Colby College and Duke University are named in his honor. He is a member of the Collegiate Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame, the Duke Sports Hall of Fame, and the North Carolina Sports Hall of Fame.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

For this biography, the author used a number of contemporary sources, especially those found in the subject’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

Full Name

John Wesley Coombs

Born

November 18, 1882 at Le Grand, IA (USA)

Died

April 15, 1957 at Palestine, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.