Jack Dunn

Jack Dunn was a right-handed pitcher who played professionally during the late 19th and early 20th century. His signature pitch was a slow curveball, and he was one of the few pitchers of his era who did not wear a fielder’s glove. Dunn was also a skilled position player, playing equally well in the infield and outfield. Jack, who stood just 5’9” and weighed around 170 pounds, was known as a fierce competitor and an extremely smart ball player

Jack Dunn was a right-handed pitcher who played professionally during the late 19th and early 20th century. His signature pitch was a slow curveball, and he was one of the few pitchers of his era who did not wear a fielder’s glove. Dunn was also a skilled position player, playing equally well in the infield and outfield. Jack, who stood just 5’9” and weighed around 170 pounds, was known as a fierce competitor and an extremely smart ball player

He began his baseball career on the sandlot diamonds of Bayonne, New Jersey. Dunn signed his first minor league contract in 1895 and two years later was pitching in the majors with the National League Brooklyn Bridegrooms. An arm injury cut short his time in the pitcher’s box, but he was versatile enough to continue on as a position player.

When Jack left the big leagues, he finished out his baseball career as a player-manager in the minors. When his active days on the diamond ended, he continued to manage and later purchased the Baltimore Oriole franchise from his former boss at Brooklyn, Ned Hanlon. During that time, he gained lasting notoriety in the baseball world by signing an unknown left-handed pitcher by the name of George Ruth. His young prospect would soon be ordained with the sobriquet of “Babe” and later became one of the greatest stars of the game. Dunn signed and sold numerous players to the big leagues including Hall of Fame pitcher Robert “Lefty” Grove.

Jack won a total of nine minor league championships as a manager, one with Providence and eight with Baltimore. His International League Orioles captured seven consecutive pennants from 1919 through 1925, a feat that is unequaled in the history of professional baseball. In post- season play, the Orioles nabbed three Junior World Series titles during that time.

As an owner, Dunn was popular with his players, paying them fairly and treating them well. During the 1920’s, Dunn’s annual Oriole payroll, which was the highest in the International League, was estimated to be around $50,000. When his team played on the road he put them up in the best hotels. Dunn’s success can be attributed to a variety of factors including his ability to use a network of scouts in cities all over the country. This group of ivory hunters was made up of his former and current players, umpires, baseball executives and loyal fans. Over the years, they supplied Dunn with a multitude of potential players.

Jack was a great motivator and possessed an astute knowledge of the inner workings of the game. He was honest and well liked, which led to him cultivating working relationships with numerous major league owners. In addition, through sheer determination, Dunn was able to keep his star players exempt from the major league draft for most of his managerial career. All of these qualities helped him establish and sustain one of the greatest dynasties in the history of professional baseball.

John Joseph “Jack” Dunn was born on October 6, 1872, in Meadville, Pennsylvania. His parents John and Maria Dunn, who were married in 1861, were born on the Canadian island of Newfoundland. John’s occupation was listed as a cooper in the 1870 census. Jack was the third oldest child in a family of three boys and two girls. The Dunns were residing in Massachusetts when their first child Catherine was born in 1864. A short time later, they moved to Cochranton, Pennsylvania, near Meadville. By 1880, the Dunn family had relocated once again, this time moving back east to Bayonne, New Jersey.

As a teenager, Jack worked as a cooper at Standard’s Barrel Company while pitching for amateur teams on evenings and weekends. Dunn and his batterymate Maurice Hickey went on to local stardom with two of Bayonne’s finest nines, the Westside Baseball Club and Centerville Athletic Club. Later, the pair signed with the Bayonne Piersols, a standout team in one of the Garden State’s most competitive semi-pro leagues. Jack married his high school sweetheart Mary in 1892, and on December 11, 1894, their only child Jack Jr. was born.

In 1895, Dunn and Hickey signed with the Binghamton Crickets of the New York State League. The following year, the Dunn-Hickey battery separated. The latter signed with Williamsport of the Central Pennsylvania League while the former hooked up with the Eastern League Toronto Maple Leafs. Jack appeared in 30 games for Toronto, 27 of them as a pitcher. At the end of the 1896 season, he was drafted by the National League Brooklyn Bridegrooms. The Pittsburgh club objected to Brooklyn acquiring the rights to Dunn because he had been playing with Toronto, the Pirates’ minor league affiliate.

After a bit of legal wrangling, a decision on the case was finally reached: Even though Jack was playing for Pittsburgh’s farm club, he wasn’t officially under contract and was therefore free to sign on with any team

Dunn made a good impression in his first campaign in the bigs, winning 14 games for Brooklyn while going the distance in all 21 of his starts. Jack also filled in at second base, third base, and the outfield that season.

The next year, Dunn’s record in the box showed 16 wins, 21 losses and a 3.60 earned run average. Once again, he displayed his versatility by making appearances at shortstop, third base, and the outfield.

In 1899, the Brooklyn team changed its name to the Superbas in honor of their new owner-manager Ned Hanlon. The Superbas went on to win the National League pennant, and Dunn’s work in the pitcher box was a key part of the team’s success. The wiry right-hander compiled a pitching record of 23 wins and 13 losses in 299 innings of work. On September 22, he tossed his first major league shutout against Cy Young and the St. Louis Perfectos, winning the game 2-0.

The following season Jack had contract issues with Brooklyn’s front office. However, he still reported to spring training at Augusta, Georgia, and continued to practice with the team until a deal could be worked out. On April 28, Dunn and the Brooklyn club finally came to a financial agreement.

Jack never got on track once the season started, and an elbow injury in early June led to his being sent home to rest. Dunn rejoined the Brooklyn club on July 14, but his bad luck continued when he injured a tendon in his pitching arm a short time later. The beleaguered pitcher struggled through the injury, but his inability to regain his old form led to his being released from the Brooklyn team on August 14, 1900.

A few days later, Jack was signed by the Philadelphia Phillies. On August 24, the veteran right-hander won his first start, defeating the New York Giants 3-1. He pitched in 10 games with Philadelphia, winning five of them. Jack tossed complete games in all nine of his starts and hit .303.

Dunn, already showing his propensity for developing players, told reporters that when his playing days were over he wanted to start a school for pitchers. He was going to charge each prospect a $25 fee for enrollment. He said at the time that if one out of hundred of his students were signed to big league contracts his school would be a success.

Jack was released by Philadelphia the following spring and signed with the Baltimore Orioles on May 11, 1901. The Birds new acquisition played the majority of his games at third base, hitting .249. He also made a handful of appearances in the pitcher’s box for Baltimore, posting three wins and compiling a 3.62 earned run average.

In early spring of 1902, the National League New York Giants contacted the Baltimore club in regard to acquiring Dunn. The Orioles initially spurned the Giants’ offer of $500 for Dunn because of questions regarding the health of player-manager John McGraw who was recovering from a knee injury. Baltimore did not want to sell Dunn until they were sure McGraw, the team’s third baseman, was healthy enough to play. After the first few days of practice in Savannah, McGraw announced in the press that he was fully healed and ready for the season. The Baltimore club, with their star third baseman back in the lineup, sold Dunn to the New York Giants on April 19th.

Jack ended up playing in 100 games for the Giants in 1902, spread out among third base, shortstop, pitcher and the outfield. McGraw would later reunite with Dunn when he took over the reigns of the New York club later in the year. Jack’s defensive versatility helped McGraw’s Giants during the season, but he finished the year with only a .211 batting average.

The next season, Jack appeared at every infield position except first base for New York, bringing his batting average up to .241.

The 1904 season was Jack’s last in the majors. The right-handed spray hitter compiled a .309 batting average while belting out 12 doubles for McGraw’s National League champs. He played every infield position for the Giants while making a few cameo appearances in the outfield. New York manager John McGraw and owner John T. Brush refused to play the American League champion Boston Pilgrims in the World Series, so unfortunately, there was no Fall Classic that year.

Jack appeared in a total of 142 major league games as a pitcher during his 8-year tenure in the majors. He posted a lifetime record of 64 wins, 59 losses and an earned run average of 4.11. At the bat, Dunn was about an average hitter, finishing with a lifetime .245 batting average.

In 1905, the former major leaguer signed on as the player-manager of the Providence Clamdiggers of the Eastern League. The pennant race that year turned out to be one of the closest in the league’s history. The season came down to the wire culminating with Dunn’s Providence club edging out Baltimore by just one-half game. Player-manager Dunn played 127 games at second base for the league champs, hitting a solid .301. The seasoned veteran led the loop in hits and still had enough life left in his legs to steal 19 bases. Dunn’s skill at running a ball club began to garner national attention, and in late August of 1905, he was mentioned as a managerial candidate for the Boston Braves. Jack did not take the job, and soon his fortunes in Providence would take a turn for the worst.

The 1906 season did not go well for Dunn as his team eventually fell to sixth place in the Eastern League standings. The Club’s poor performance, just one year removed from winning the championship, led to Dunn’s being released by Providence at the end of the year.

It was through a chance encounter a few months later with Oriole owner Ned Hanlon at the Baltimore Sports Bar “The Diamond” located on 519 N. Howard Street in Baltimore, that led to Dunn signing with Baltimore. During the unplanned meeting between the two men, Hanlon offered Jack Dunn the job of player-manager for his Eastern League Orioles for the upcoming season. Jack accepted the terms and on January 12,1907, was officially introduced in the Baltimore press as the new skipper of the Orioles. The Birds’ new leader led the team to a sixth-place finish in 1907. Jack played 98 games at second base, .222 and stealing 16 bases.

Dunn’s long-range plans included buying his own franchise. In October of 1907 he offered Rochester owner C. T. Chapin $ 10,000 for his ball club. Chapin declined, saying in the press that Dunn’s offer was much too low so the deal fell through.

The following season, Dunn guided Baltimore to the Eastern League Championship

The Oriole leader suffered a knee injury in August but still managed to play 90 games at second base, hitting .245.

The following year, the Baltimore club slumped badly. In the off-season Dunn was finally able to realize his dream of buying his own franchise. Jack began his negotiations with owner Ned Hanlon in the fall of 1909, and the deal was consummated in late November. The Sporting Life noted that sale price for the Oriole team was $35,000, but other sources have listed a higher figure. It was rumored that Dunn borrowed money from Philadelphia Athletics owner Connie Mack in order to purchase the club. Over the years, various comments in Sporting Life have verified that Mack was indeed an Oriole shareholder. Dunn’s attorney Charles Knapp and former Oriole catcher Wilbert Robinson were named directors of the franchise.

The Birds played much better under their new boss, climbing back up to third place in the standings. Part of the team’s success was due to rookie pitcher Lefty Russell, who won 24 games and led the Eastern League in strikeouts. Dunn sold Lefty to the Philadelphia A’s owner and manager Connie Mack for what was considered to be the astronomical price of $12,000, the most money ever paid for a ball player up to that point in professional baseball

For the next few years Dunn’s club experienced mixed success on the diamond, but he continued to do well financially by selling his best players to the major leagues. Jack also had a small ballpark built in the Back River section of Baltimore County. He used this for exhibition games and to avoid the Blue Laws, which prohibited ball playing in the city on Sunday.

The Orioles played numerous exhibition games against major league clubs during Dunn’s tenure with Baltimore, coming out on the winning end on many occasions.

In 1912, the Eastern League changed its name to the International League due to the two Canadian teams that were now members of the circuit. Fourth- and third-place finishes followed, but the 1914 season would mark a milestone in Baltimore baseball history.

In the winter of that eventful year, Jack Dunn signed a young pitcher from St. Mary’s Industrial school in southwest Baltimore. This school was a training facility for boys who were orphans or wards of the state. As the story goes, Mt. St Joseph High School baseball coach Brother Gilbert was trying to hold on to his star pitcher, a youth named Lee Meadows, for another season. In order to keep Meadows from signing with the Orioles, Brother Gilbert recommended St Mary’s southpaw ace George Ruth to Dunn. The rest is baseball history.

On February 14, 1914, George Herman Ruth signed with Jack Dunn’s International League Orioles. In order for Ruth to be released from St Mary’s, Dunn had to become his legal guardian. The former incorrigible youth from the hard-scrabble streets of Baltimore was now a Baltimore Oriole under the care and guidance of his new mentor Jack Dunn.

The Orioles held their spring training in Fayetteville, North Carolina, that year. It didn’t take long for Ruth to make his mark with the team. Dunn’s latest prospect pitched good ball against major league competition in addition to playing solid defense as the team’s left-handed shortstop. The future Sultan of Swat also showed his proclivity for power hitting by belting the longest home run ever recorded in the city of Fayetteville. It was during those Oriole practice sessions in North Carolina that Ruth was christened with the everlasting moniker of Dunn’s baby, later shortened to Babe. A friend of Dunn’s named Scout Steinmann, who was managing one of the Orioles’ intra-squad teams, gave the nickname to the future idol of the baseball world. By the end of spring training, Ruth had earned his way into the number two-spot in Dunn’s pitching rotation.

The opening of the 1914 baseball season presented a unique situation for Baltimore baseball fans. Not only were Dunn’s Orioles representing Baltimore in the International League but a new professional team, the Terrapins, had also taken up residence in Charm City. The Baltimore Terrapins were members of a new major circuit called the Federal League that was beginning its inaugural season in 1914. To make matters worse for Dunn, the Terrapins built their ballpark directly across the street from his Oriole grounds.

Although both teams rarely played on the same day in Baltimore, local fans took to the Terrapins big league brand of ball and shunned Dunn’s Birds at the box-office. The drop in attendance affected the Oriole magnate’s ability to make payroll, and soon he began to look for ways to remedy the situation.

As early as June 17, Dunn announced in the Baltimore press that he had been offered $62,500 for 49 shares of his ball club by investors in Richmond, Virginia. He said at the time if the Baltimore fans did not start supporting his team, which was in first place, he would have no choice but to relocate the franchise.

The situation never got any better for Dunn in Baltimore, and soon he started selling his best players to the majors in order to cover team expenses. Birdie Cree, Bert Daniels, Dave Danforth, Ensign Cottrell, and a host of others were dealt to big league clubs in order to keep his Oriole team in the black. However, the most important transaction to the game of baseball involved a three-player deal with Boston Red Sox owner Joe Lannin. In early July, Dunn sold star pitcher George Ruth along with catcher Ben Egan and another tosser named Ernie Shore to the Red Sox. The sale price for this deal has been reported to be anywhere from $ 8,500 to $ 28,000. Egan would go on to have his best days in the minors, Shore turned out to be a pretty fair pitcher, but Ruth would gain baseball immortality as the undeniable Sultan of Swat. Dunn had offered Ruth to his friend Connie Mack, who turned him down. Mack said that he did not have the cash for the deal due to the high salaries he was paying his players to keep them from jumping to the Federal league.

The situation never got any better for Dunn in Baltimore, and soon he started selling his best players to the majors in order to cover team expenses. Birdie Cree, Bert Daniels, Dave Danforth, Ensign Cottrell, and a host of others were dealt to big league clubs in order to keep his Oriole team in the black. However, the most important transaction to the game of baseball involved a three-player deal with Boston Red Sox owner Joe Lannin. In early July, Dunn sold star pitcher George Ruth along with catcher Ben Egan and another tosser named Ernie Shore to the Red Sox. The sale price for this deal has been reported to be anywhere from $ 8,500 to $ 28,000. Egan would go on to have his best days in the minors, Shore turned out to be a pretty fair pitcher, but Ruth would gain baseball immortality as the undeniable Sultan of Swat. Dunn had offered Ruth to his friend Connie Mack, who turned him down. Mack said that he did not have the cash for the deal due to the high salaries he was paying his players to keep them from jumping to the Federal league.

The Birds minus their key players limped into a sixth-place finish. With the 1914 season now over, Dunn with no viable options available, made plans to relocate the Baltimore franchise to Richmond, Virginia, for the 1915 season. Baltimore’s Federal League team had literally put Dunn out of business.

In December, Dunn and Connie Mack, who still retained a financial interest in the Baltimore team, along with International League President Ed Barrow, traveled to Richmond to finalize the move.

A few weeks later, Dunn and a group of local businessmen paid a $12,500 territorial fee to the Virginia State League. This payment along with a few other loose ends that Dunn took care of cleared the way for the Baltimore Orioles to officially become the Richmond Climbers.

Dunn’s club presented a talented lineup that had a number of former major leaguers on the roster including Johnny Bates, Angel Aragon, and George Twombley. Unfortunately, even with this veteran leadership, the team played inconsistent ball, finishing with a record of 59 wins and 81 losses. However, the club drew decent crowds at the gates, so Jack did well financially. In addition, he made a nice profit by selling off some his better players including pitcher Allen Russell, Lefty’s brother, to the Yankees for $4000.

Over the next few months Dunn’s baseball plans would change drastically as the financially troubled Federal League disbanded after the 1915 season. Sensing an opportunity, the savvy businessman sold his shares of the Richmond ball club to local Virginia investors and severed his ties with the team.

Dunn then purchased the struggling Jersey City franchise for $75,000 and moved that team to Baltimore for the start of the 1916 International League season. After the deal for his new club had been finalized, he purchased the old Federal League ballpark for an estimated price of around $30,000. He also took out an eight-year lease on the property. Dunn’s former grounds across the street, which had been in use from 1901 through the 1914 season, were eventually torn down.

Major league baseball suggested to Dunn that he help out the disbanded Terrapins by amalgamating the franchise with his own Oriole team. He flatly turned them down saying in the press that “he wasn’t amalgamating with anybody.” As it turned out, Baltimore’s Federal League team was the only club from the defunct circuit that never received any type of financial compensation.

Jack was determined to stock his new Oriole roster with high quality players that he could groom and eventually sell to the big leagues. In early 1916, the Baltimore magnate announced in the press that he had made a deal with the Philadelphia A’s and New York Yankees that gave him access to all of their surplus players.

By August of 1917, an article in the Washington Post noted that Dunn had been managing in the minors for 12 years and sold 23 players to the major leagues. The article added that Dunn had made over $150,000 from those sales along with acquiring numerous players that were included in the deals.

The 1918 season started out with ten minor leagues in operation. Because of wartime hardships and lack of fan support, though, the International League was the only minor circuit that was able to finish out the year. Players being drafted for military service, taking jobs related to the war industry, and jumping to independent leagues were some of the problems that Dunn faced that year. However, due to his resourcefulness, he was able to deal with all of these issues and still field a competitive and financially successful club.

At this time, Dunn in an article in the Washington Post announced his opposition to major league baseball imposing a draft on the International League. Jack thought it unfair that big league teams could purchase his star players for the discount price of $5000 when he knew that in most cases they were worth much more. The Orioles and other teams in the high minors had informal agreements with major league clubs in regard to the farming out and selling of their excess players. Dunn said in the press “that he would sign players from the sandlots and lower minor leagues if the disgruntled major league owners voted to stop dealing with his organization.” The working relationships that Dunn had previously enjoyed with big league clubs were irreparably broken because of his stand on the draft. Philadelphia’s A’s owner Connie Mack was the only exception and remained Dunn’s friend throughout.

The 1919 season saw the start of one of the greatest dynasties in the history of professional baseball. Dunn’s Birds won their first of seven straight championships that year, finishing eight games in front of the second-place Toronto Maple Leafs. Jack’s Oriole squad included the league’s highest average hitter, outfielder Otis Lawry (.364), and the league’s top pitcher in wins and strikeouts, Rube Parnham (28 and 187).

In the early part of the 1920 season, Dunn signed future Hall of Fame pitcher Robert “Lefty” Grove. The fire-balling portsider was playing for Martinsburg in the Blue Ridge League when he was discovered by Jack Dunn Jr. The younger Dunn served as the team’s business manager, secretary, and in this case, scout. The Martinsburg club was in need of a new outfield fence and some equipment, so Dunn Sr. was able to purchase Grove for the bargain price of $3,500.

In addition to Grove, Dunn’s two-time champs showcased outfielder Merwin Jacobson’s league-leading .404 batting average and Jack Ogden, who along with Toronto’s Red Shea topped the circuit with 27 victories. The red-hot Baltimore club closed out their schedule with a 25-game winning streak.

The following season would be the most successful in the storied history of the Baltimore franchise. The 1921 club won 119 games while featuring ace pitcher Jack Ogden, who won 31 games and first baseman Jack Bentley who batted .412 while winning 12 games as a pitcher. The high-flying Birds put together another amazing winning streak that year, this time making it all the way to 27 straight games.

The 1922 campaign started out with more of the same for the other teams in the International loop. Finally in June, the owners around the league decided to do something about the Baltimore club’s dominance of the circuit. The International League executives held a secret meeting in New York without Dunn present. The group then issued an ultimatum to the Oriole leader. The crux of the statement was that if Dunn did not start selling off his best players to the majors, the owners would vote for the major league draft to be reinstated. These outclassed clubs figured they would rather lose out on player sales, as opposed to not having any fans showing up to their ballparks. Attendance was suffering around the league because it seemed now that the Orioles usually had the loop wrapped up by midsummer.

The Baltimore team, still loaded with stars, went on to win its third pennant in a row that year. Dunn, acquiescing to the wishes of the league owners, sold first baseman-pitcher Jack Bentley to John McGraw’s New York Giants for $72,500.

The 1923 Orioles started out the preseason in early March with their annual spring training workouts in the city of Winston Salem, North Carolina. Sadly, a few days into practice, Jack Dunn Jr. who had been battling pneumonia for weeks, passed away at his home in Baltimore. He was 28 years of age.

In the days before young Jack’s death, Dunn Sr. could be heard pacing the hallways outside his son’s room imploring him to “fight it” and “to stay with those he loved.”

Jack Jr. briefly regained consciousness long enough to recognize his wife before expiring in his father’s arms. Dunn Sr, as one would expect, was emotionally and physically devastated by the loss of his beloved only son.

Dunn Jr. had been a star football and baseball player at City College (High School) in Baltimore. He played a few seasons of professional baseball, but his preordained destiny had been to take over the reigns of the Baltimore franchise when his father stepped down.

Dunn Jr.’s funeral was held at St. Mary’s of Govans Catholic Church and was attended by a multitude of baseball dignitaries and players, past and present. In addition hundreds of telegrams were sent to the Dunn family expressing condolences.

After the services, Dunn Sr. relinquished all team duties to his trusted captain Fritz Maisel and retreated into a grief stricken pall that lasted for months. Dunn finally rejoined the Baltimore club in early June and with a heavy heart resumed his managerial role. The Birds, inspired by the tenacity of their leader, captured the International League crown for the fourth straight year, finishing 11 games in front of Rochester. Lefty Grove led the league with 330 strikeouts to go with 27 wins while Rube Parnham finished 33-7 for a league-best .825 winning percentage. Dunn sold star second baseman Max Bishop to the Philadelphia A’s for $25,000 after the season in his continued effort to level the league playing field.

For the next two years, Dunn’s Oriole teams continued to dominate, setting the unprecedented mark of winning seven consecutive International League pennants.

During that time he sold pitcher Lefty Grove to the Philadelphia A’s for the tidy sum of $100,600. This was the highest price ever paid for a player up to that point in baseball history, exceeding the Boston Red Sox’ sale of Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees by six hundred dollars. Dunn’s fellow International League owners voted at this time to reinstate the major league draft although the stubborn Dunn continued to sell his players to the highest bidder.

Baltimore’s championship run finally ended with a second-place finish in 1926. In October of that year, the Baltimore Sun reported that Dunn had sold 29 players to major league teams and received a total of $404,100 in cash from these transactions.

The loss of his key players eventually began to take its toll, and Dunn’s Birds dropped dramatically in the standings in 1927 and 1928. Nonetheless, he still cashed in by selling pitcher George Earnshaw to the Philadelphia A’s and batting champion Dick Porter to the Cleveland Indians for a combined $80,000.

In the fall of 1928, Boston Braves owner Emil Fuchs asked Dunn to manage his team, but Dunn turned down the offer, saying he was happy in Baltimore and determined to rebuild his Oriole franchise.

On October 22, 1928, the avid hunter and sportsman was competing in field trials with his prized hunting dogs just a few miles north of Towson, Maryland. Dunn was on horseback, leaning forward, watching his dogs chase down a bird, when he toppled from the saddle, a victim of a fatal heart attack at the age of 56. Members of the crowd immediately sought help while one of the judges, Reverend E.C. Callahan, administered the last rites of the Catholic Church to the fatally stricken Dunn. A short time later, Dr. Daniel from the nearby Thomas Jennifer School arrived at the field. Sadly, there was nothing the physician could do for the Orioles’ esteemed leader, who was pronounced dead on the scene.

Dunn, who never smoked or drank, had been under doctor’s care for a coronary condition that had been brought on years earlier by the death of Jack Jr. His wife Mary A. Dunn, along with his sister Mrs. P.J. Spain of Baltimore and brother James Dunn of Chicago, and his grandson Jack Dunn III survived him.

Jack Dunn’s funeral was held at St Mary’s of Govans Catholic Church, and he was buried beside his son in the adjoining cemetery. Hundreds of mourners, including executives from every team in the International League, attended the services. Floral arrangements arrived to the church in droves, including a large display sent by baseball Commissioner Kennesaw Mountain Landis. Connie Mack, Clark Griffith, Ned Hanlon, and J. Conway Toole (president of the International League) were just some of the baseball dignitaries who were present for the Requiem Mass.

Jack’s wife Mary took over as the team’s owner and remained in that capacity until her death in 1943. Jack Dunn III became the owner from that point on and ran the club until the St. Louis franchise was moved to Baltimore for the start of the 1954 season.

Jack Dunn Sr. guided his teams to nine championships during his illustrious career. His many accomplishments as a player, manager, and team owner have assured him his place in baseball history as one of the game’s most influential figures.

Sources

The Baltimore Sun

The Bayonne Evening Review

The Bayonne Herald

The Bayonne Evening Times

The Bayonne Daily Times

Washington Post

Baseball Magazine

Sporting Life

Ancestry.com

Baseball-reference.com

Minorleaguebaseball.com

Retrosheet.org

SABR.org

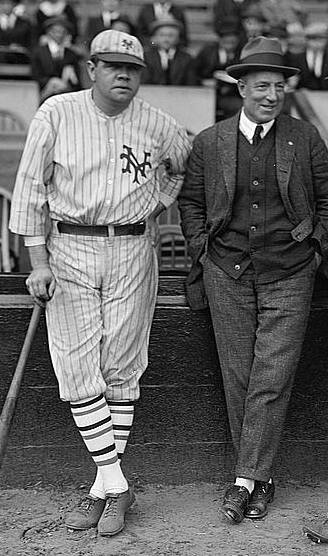

Blair Jett for contributing the photograph of Jack Dunn

Johnson, Lloyd, and Miles Wolff, eds. Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball. 3rd ed. Durham, NC: Baseball America, 2007.

Keenan, Jimmy. The Lystons: A Story of One Baltimore Baseball Family and Our National Pastime, self- published 2009

Wright, Marshall. The International League: Year-by-Year Statistics 1884–1953. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 1998.

Full Name

John Joseph Dunn

Born

October 6, 1872 at Meadville, PA (USA)

Died

October 22, 1928 at Towson, MD (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.