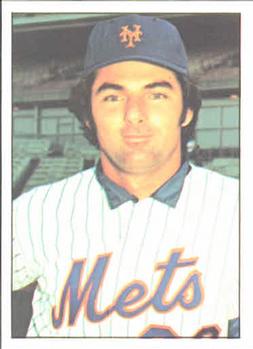

Jerry Cram

Jerry Cram’s signature moment in the big leagues came on September 11, 1974. He threw eight scoreless innings in relief for the New York Mets — the 17th through the 24th of what became a 25-inning loss to the St. Louis Cardinals. If the Mets could only have scratched across a run, Cram would have been the marathon’s hero. Nonetheless, this strong performance was instrumental in the team’s decision to put Cram on its Opening Day roster in 1975.

Jerry Cram’s signature moment in the big leagues came on September 11, 1974. He threw eight scoreless innings in relief for the New York Mets — the 17th through the 24th of what became a 25-inning loss to the St. Louis Cardinals. If the Mets could only have scratched across a run, Cram would have been the marathon’s hero. Nonetheless, this strong performance was instrumental in the team’s decision to put Cram on its Opening Day roster in 1975.

Cram was an unheralded amateur signed by the Minnesota Twins in 1967. The righty reached the majors two years later, but he had just four short stints there — five games with the Royals in 1969 and four with them in 1976, book-ending 14 with the Mets in 1974 and ’75. “Good enough to get there, not good enough to stay, that’s the way I put it,” he said.

Yet he made his mark as a pitching instructor in the minor leagues, starting in the Royals system in 1980 and continuing through 2017 with the San Francisco Giants chain. He had a hand in the success of many notable future big-leaguers along the way.

Gerald Allen Cram was born on December 9, 1947 in Redondo Beach, California. His father, Robert, served on a destroyer in the U.S. Navy during World War II as a radar technician. After the war, he became a building contractor. Robert’s wife, Rosemary, worked in real estate. They were married in 1945.

Cram never strayed too far from the Los Angeles area while growing up. His family moved to Placerville in El Dorado County when Jerry was in eighth grade. He then attended Ponderosa High School, where he was active in all three major sports. He played forward in basketball; in football, he was a quarterback, offensive and defensive end, and punter. “Later I also kicked field goals,” he said. But baseball was his primary sport, and pitching his greatest talent.

Cram suffered a cerebral hemorrhage during his sophomore year that cost him a full year of participating in sports. His family moved again, this time to Lake Elsinore in Riverside County, where Cram focused solely on baseball beginning with his junior year at Lake Elsinore High School. After graduating, he attended Riverside Community College, where he continued to pitch. Though all 20 big-league clubs bypassed him during the 1967 draft, he got his break after participating in open tryouts with the Los Angeles Dodgers.

After walking on at the tryout camp, Cram was called back by the Dodgers for another look. “One was in Dodger Stadium and the last one was in Riverside County somewhere, I can’t remember exactly,” he said. “Some of the guys that were scouting at the time, some of the big scouts, were there for the tryouts, especially for the one in Chavez Ravine.”

He recalled being nervous — “Yeah, especially because I come from a small school, and I’m kind of a shy type anyway” — and realized it was his big chance. “I was aware there were scouts,” said Cram, who successfully caught the eye of one. “It ended up Jess Flores with the Twins called and they wanted to come over and sign me, and that’s pretty much how it happened,” he said.

Cram was assigned to St. Cloud in the short-season Northwest League. There he registered a 2.70 ERA and 6-2 record in 24 games, four of which were starts. He had 94 strikeouts in 70 innings. In one game on July 19 against Duluth-Superior, he struck out the last nine batters of the game in relief to preserve the win.1

The Twins then moved him up to Wilson in the Class-A Carolina League for 1968. Starting 29 times in 30 appearances, he won 16 games, lost just 10, and had 204 strikeouts in 208 innings. Yet despite his very high strikeout ratios, he wasn’t a flamethrower back then — it only meant that he was a strike-thrower, he explained.

“I could throw strikes; in Wilson I threw a four-seam fastball and an overhand curveball. I could throw my curveball inside and outside, but I didn’t walk anybody [just 2.1 per 9 innings at Wilson]. You get a lot of swings and misses, you’d get guys guessing. I probably struck out more guys with fastballs than curveballs.

“As you get higher (in the minors), I didn’t have that kind of stuff. But as I got to Triple-A I probably quit trying to strike people out. As a reliever I went to a sinker and then I developed some other pitches.”

The Twins then failed to protect him from the expansion draft, and Cram was scooped up by the Kansas City Royals. “You’re a young kid, you don’t really understand, but it’s probably a good thing,” he said. “It was just like being traded, only it happened when I was much younger and not really understanding it.”

Cram reported to Kansas City’s instructional league team in Sarasota, Florida, where he made an impression on Joe Gordon, the Royals’ first manager. “On a couple of occasions, Cram showed me as good a curve as I’ve ever seen,” said Gordon. “He has a curve that breaks straight down. You should see lefthanders swing at it. He has them chopping on it. It looks like they’re swatting flies.”2

Gordon compared the pitch to the one thrown by Camilo Pascual, and said Cram could get it over “any time he wants to.” The skipper added, “He is not overpowering, but he can get by with his fast ball (sic). He pitched ten scoreless innings when I saw him. I’d have to say he’s a good prospect.”3

Cram prepped in Fort Myers, Florida with the big club during spring training in 1969. He then vaulted all the way to Triple-A Omaha to begin that season. He got off to a rocky start, with a 0-1 record and 12.38 ERA in his first eight games before settling down. But his appearances soon dried up in favor of more seasoned hurlers, and he was assigned to High Point-Thomasville, where he spent the month of June.

There Harry Malmberg, the manager of the Class-A club, echoed Gordon’s earlier sentiments. Malmberg said that Cram’s curve rivaled that of most hurlers in the majors at the time. “He definitely has big-league stuff,” he proclaimed after Cram threw a one-hit shutout on June 2 against Kinston. “Few pitchers in the majors have as good a curveball.”4

Cram said the curveball was always a plus pitch for him, and that it just came naturally to him after he began tinkering with it at a very young age. “Yeah, I knew I had a good curveball,” he said. “I always threw a curve, even from when I was a kid, in Little League. I threw like a drop.”

He credits Ken Hunt, his baseball coach at Lake Elsinore High, with helping him refine it. “He taught me the proper technique in throwing the curveball, and actually my junior and senior year the curveball got way better,” Cram said.

After posting a 1.26 ERA in eight starts at High Point-Thomasville, Cram returned to Omaha to begin July. He threw a complete game shutout against the Denver Bears in his first game back on July 3, allowing seven hits in the 3-0 victory. “He’s got his fastball back, and it’s a good one,” said catcher Jim Campanis.5 Cram remained with Omaha through the end of the American Association season, going 10-4, 4.21 in 126 innings and 15 starts, helping his club to an 85-55 record and first-place finish.

Cram’s final numbers in Triple-A weren’t stellar — he allowed 144 hits with a 1.44 WHIP — but they were good enough to earn a September call-up to the big leagues. His debut came on September 3, when he pitched two scoreless innings in relief against the Detroit Tigers at Municipal Stadium, in what became a 4-2 victory for Detroit. After retiring Jim Northrup, his first batter, on a grounder to first, he allowed two hits and a walk with one strikeout — future Hall of Famer Al Kaline, the second batter he faced.

“I believe it was a swinging strike; a fastball,” Cram recalled. If his nerves were jumping as Kaline, a perennial All-Star, strode to the plate, he said he didn’t really remember. “I probably didn’t know who was coming up that inning,” he said. “No, I don’t remember a whole lot about it.

“I knew who he was, yes — I guess the concentration of being out there and trying to throw strikes was more than enough for me, and I was lucky enough to strike him out.”

The real thrill for Cram was walking out to the mound in a big-league game for the first time. “Well, it was obviously pretty exciting getting called up,” he said. “It’s quite an experience, your first walk across those white lines.”

His first start came on September 8, a no-decision in which he allowed four hits and three earned runs over four innings in a 7-3 win vs. Oakland. He fared better in his next turn against the Seattle Pilots on September 15, allowing one earned run and four hits over seven innings as the losing pitcher in a 3-2 defeat. He walked one batter and struck out five. It was his last start in the big leagues — and his longest outing at the top level until his effort in the marathon of 9/11/74.

Cedric Tallis, then the Royals’ executive vice president, said that Cram, along with Al Fitzmorris, had impressed the brass in 1969. “They showed us they could come out and get guys out last year,” Tallis remarked that winter. “Cram has that great curve and Fitzmorris has an excellent sinker. Both get the ball over.”6

Cram then spent all of 1970 at Omaha, going 7-9 with a 3.21 ERA in 27 starts. There were some good games, including a shutout against Iowa on May 20 in which he stranded 10 baserunners and another on August 18 at Evansville.7 However, they were offset by some bad ones, most notably a start vs. Denver in the playoffs where he lasted only one-third of an inning and gave up five runs, four of them earned.8

His 1.44 WHIP was the same as the one he registered at Omaha the previous year, but this time he was bypassed by the big club once September rolled around. “Just one of those things, I just didn’t get a chance to go back to the big leagues,” he said. “Actually I was the last pitcher sent to the minor leagues that spring. So, I felt that I did what they wanted me to do, it just didn’t work out.” It proved a precursor of things to come — he spent the next two seasons at Omaha without a sniff of the big leagues.

Again doing what the organization wanted, Cram played winter ball in Latin America for the first time in the winter of 1970-71. He was with Tiburones de La Guaira in the Venezuelan League. Though his won-lost record was just 5-10, his ERA was a tidy 2.76.

With Omaha in 1971, Cram was consistent, recording a WHIP just a tick under what it was the previous two years at Triple-A, but his record slipped to 5-11, 4.35. That winter, he went back to Venezuela, this time joining Tigres de Aragua. In January 1972, however, he was released along with four other American players in a dispute with the league. Allegedly they had sought bonuses from the Aragua club to take part in post-season play. One of the five, Graig Nettles, called it “a big frameup.” Bobby Maduro, coordinator for Inter-American Baseball in the commissioner’s office, said that he was seeking statements from the players. 9 Venezuela’s National Institute of Sports planned to conduct its own investigation of the affair, which had the nation’s sportswriters up in arms.10

The Sporting News noted that December that all five players denied the charge, in another report about Venezuela’s “higher than average dismissal of imported players.”11

Returning to Omaha, Cram bounced back in 1972, although he was used lightly. He was 3-4 with a 3.05 ERA in 26 games, almost all out of the bullpen. The Royals then traded him to the Mets for pitcher Barry Raziano on February 1, 1973. Cram spent his fourth consecutive year toiling at Triple-A, this time with Tidewater of the International League.

He went 6-0, 3.68 that year, with just 30 appearances, all in relief. In August, after Tidewater starters went all the way in 42 of the team’s first 99 games, Cram observed, “With this club a relief pitcher has to throw a lot in the bullpen.”12 Later that month, he was sidelined by a back spasm that forced him to wear a neck brace.13

Cram seemed destined for the minors yet again in 1974. “I wasn’t invited to spring training, I was a little disappointed,” he said. And one day before the season started, he let his feelings show.

“Billy Connors (minor league pitching coordinator) came over to me one day and said ‘I need you to go over and throw batting practice for the big league club,’” Cram recalled. “And I said ‘Y’know, Billy, I wasn’t good enough to go over in the beginning, I don’t think I’m good enough to go over there now.’”

Cram laughed while telling the story. “I made every trip after that…he sent me on every trip in the minor leagues,” he said.

Then something clicked, and Cram began to display the promise from earlier in his career. And when his next opportunity to pitch to the Mets’ big-leaguers came up, during an exhibition game that summer, he didn’t opt out.

“We played the Mets in Tidewater, and I had gotten hurt; I pulled a rib cage a little bit,” he recalled. “I said I’m not missing this game, I’m gonna pitch against them. So I had the trainers ‘ace-bandy’ my chest a little bit, and good enough that I could pitch. And I did well. Then later on in the year I ended up getting called up.”

After posting a 2.92 ERA in 36 games and 71 innings, Cram replaced injured pitcher George Stone. He was riding a string of four saves and two victories over his last seven appearances. “Cram was the hottest pitcher down there,” said General Manager Bob Scheffing.14

Cram said that being around Tom Seaver, Jon Matlack, and Jerry Koosman — among the best pitchers in baseball — was an eye-opener. “All those guys used to hold their own meetings prior to pitching, and they were all very astute about what they were talking about,” he recalled. “And then Seaver talked about pitching to guys, and he went through the whole lineup. And he’d say ‘Now we’re going to talk about them with men in scoring position,’ and I went ‘oh, we’re talking about a whole different level here, baby.’”

Cram was unscored on in his first three appearances before taking a loss. He surrendered a pinch-hit home run to Cliff Johnson on August 28 in a game that the Houston Astros won 3-2 in 10 innings.

His next appearance on September 11 would prove the most memorable of his big-league career. In the 18th inning, he got the first (and only) hit of his big-league career off Claude Osteen. “A solid line drive over the shortstop’s head,” he said.

Inning after inning, the Mets couldn’t score, and Cram kept walking out to the mound. He said he didn’t stop to think about how many more innings he could go. “You get three outs, you go back in, you get three outs, you go back in,” he said.

As each frame ticked by, Cram remembered Rube Walker, the Mets’ pitching coach, getting fidgety. “Rube kept coming over to me and saying, ‘You okay, kid?’ I said, ‘Yeah Rube, I’m fine, I’m fine.’ I don’t know if it was a superstition or what, but he came over just about every inning, especially after about five innings.

“I understood because I hadn’t pitched that many innings, but I knew myself I was fine, it wasn’t a surprise to me to step up and go eight innings,” he said. “In the minor leagues, whenever I would spot start, I didn’t surprise myself by being able to pitch six, seven, maybe even eight innings or completing the game.

“Actually I was a short reliever all year, but once I got called up I don’t remember pitching any more than maybe two innings until that night, or that morning I should say.”

In the 25th inning, Cram gave way to Hank Webb, whose wild pickoff attempt enabled Bake McBride to sprint all the way around from first with what held up as the winning run. Finally — mercifully — the game ended at 3:12 a.m. after 7 hours and 4 minutes. Cram joined his teammates on the slow trudge to the clubhouse and slumped in front of his locker, too tired to even pull off his jersey.

“I remember just going to my locker and sitting there, I was drained,” he said.

Cram believes that outing raised his stock with the team brass, setting himself up to break camp with the big club in 1975 for the first time in his professional career. “I think so,” he said. “I think at that point in my career, one of the things I was proud of, I was able to get back to the big leagues after five years in the minor leagues. And then to make the club the next year.”

Cram appeared in five more games before the season ended. He finished with a 1.61 ERA in 22.1 innings. One of his fondest memories was being part of the Mets trip to Japan following the 1974 season. One day, he sat “three-quarters of the way” down the right-field line and watched the two premier power hitters on the planet — Hank Aaron and Sadaharu Oh — match up. “I got to see one of the greatest home-run hitting contests in the game,” he said.

Before the 1975 season started, the Mets had stripped the pen of veteran arms like Bob Miller, Jack Aker, Ray Sadecki, and even star closer Tug McGraw. Thus, Cram was a big leaguer on Opening Day.

After going unused by the Mets in the first four games of the season, Cram strode to the mound in the ninth inning of a 3-3 game against the Philadelphia Phillies at Veterans Stadium. He promptly gave up a long home run to Mike Schmidt and took the loss. He didn’t pitch again until April 30, throwing two scoreless innings in a 7-4 loss to the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field.

He made only two more appearances after that, ending with a one-inning stint against the Astros May 18 in which he didn’t allow a run. He was then removed from the 40-man roster and outrighted back to Tidewater to make room for Bob Gallagher, a spare outfielder. His career with the Mets was done.

“Things didn’t work out; I only pitched five innings in like six weeks or something like that, and got sent back to Triple-A,” Cram said. “It was just one of those things.”

Cram went on to put up solid numbers for the Tides the rest of the way — an 8-1 record with a 2.88 ERA and 1.18 WHIP to go with 43 hits and 16 walks allowed in 50 innings. But it wasn’t enough to convince the Mets to bring him back.

“I did well the year before in the short time I was there, and got off to a tough start in ’75, but you go down and do your job,” he said.

Cram had married Cathy Edson, a girl from Omaha, and purchased a home back there. They had two children, Gerald Jr. and Andrea. Cram requested a trade back to the Royals if he was no longer in the Mets’ plans.

“I actually asked them the day they sent me down, if I’m going to have to play in the minor leagues if they could get me back with Kansas City, and that did happen the next year,” he said. In January 1976, the Mets traded Cram back to the Royals for Randy Hammon, a pitcher who never appeared in the big leagues.

Cram then became a staple on the Omaha pitching staff for the next five years, appearing in 209 games for the club from 1976 to 1980. He got into a last two in 1981, his second year as a player-coach.

A workhorse for Omaha in 1976, Cram logged 102 innings in 51 appearances, all but one in relief, and posted an 11-3 record. His team went 78-58 and won the Eastern Division of the American Association by 10 games. In the playoffs against Denver, Cram appeared in three games, holding the Bears scoreless over three innings in Game Two.15

After that series ended, Kansas City rewarded his efforts by calling him up for the rest of the parent club’s season. He was immediately called upon, getting into his first game with the Royals after a seven-year absence on September 10. He gave up two runs in 1 1/3 innings in an 18-3 pasting at the hands of the Twins, his first professional organization.

The Royals were on their way to a divisional championship and their first-ever playoff appearance, so Cram was mostly a spectator. He did not appear again until September 23, when he pitched two scoreless innings without a hit in the Royals’ 8-1 loss to Oakland.

His final appearance came on September 27, when he became the fourth of five Royals pitchers to enter a wild sixth inning against the A’s. After Sal Bando homered, Dennis Leonard plunked Don Baylor, who charged the mound and then punched George Brett when he tried to intervene.

After Steve Mingori and then Bob McClure relieved, Cram came in and allowed a double to Phil Garner before throwing a wild pitch with Bill North at the plate. He was promptly relieved by Ken Sanders in what became an 8-3 A’s victory. With that, his time in the big leagues was complete.

Cram then returned to Omaha for his final sojourn as a player. He had one of his best seasons in 1977, going 10-5 with a 2.01 ERA and 1.10 WHIP, with 81 hits allowed in 103 innings. Though his performance helped Omaha clinch a divisional championship yet again,16 it wasn’t enough for another trip to the big leagues.

From there Cram’s numbers began to fade, with nearly a hit per inning allowed in 1978 (3.45 ERA and 1.34 WHIP in 99 innings), and more hits than innings pitched in both 1979 and 1980, his first year as a player-coach. He was activated in early May that season and went on to allow no runs and only four hits in his first 12 2/3 innings pitched, finishing 6-5 with a 4.09 ERA and 1.39 WHIP for the year.

He appeared in two games late in 1981 after being activated again for the stretch run. “What happened was they put me on the roster at the end of the year when we were going to be in the playoffs, and I pitched one inning in relief, and then I started the second game of a doubleheader right near the end of the year so we could set our rotation,” Cram recalled. “I pitched four innings — actually I went out for the fifth inning and I didn’t get nobody out in the fifth, so that was the end of that story.”

However, it marked his segue into his full-time career as a coach. “Going right from being a Triple-A player to a Triple-A pitching coach was kind of a challenge, but I made the transition pretty easy,” he said.

Cram remained at Omaha until 1983, when he was shifted to the Royals’ rookie-league club in Butte, Montana at midseason. The following year the Royals made him a roving pitching instructor, a role in which he remained through 1997.

“The one thing I enjoyed was the levels of teaching,” he said. “When you went to rookie ball you taught a different way than you did when you went to Triple-A. I enjoyed it; I liked it that way. I liked the fact that I could use different techniques in different levels.”

He then moved on to the Colorado Rockies’ system from 1998 through 2000. After that, he got a call from Jack Hiatt, a former big-leaguer who was working at the time for the Giants, and got hired there before the 2001 season.

“I had pitched against him when he was managing at Wichita, and he asked me questions about some of the people that tutored me with the Royals,” said Cram. “He knew those people and I was able to get hired.”

He started out with the Hagerstown Suns in the South Atlantic League before moving on to San Jose in the Class-A California League, where he served as pitching coach through 2003. He then moved on to the Salem-Keizer Volcanoes in the short-season Northwest League as pitching coach from 2004 through 2008 before returning to San Jose in 2009 and 2010. Then it was back to Salem-Keizer for two more years before becoming assistant pitching coach for the Double-A Richmond Flying Squirrels in 2014. He then served as pitching coach for the Augusta GreenJackets, a low-A affiliate, in 2015-16 before returning to Salem-Keizer yet again for the 2017 season.

He had a hand in the development of many well-known big-leaguers along the way, from Danny Jackson, Bud Black, and Charlie Leibrandt in the Royals’ system to Tim Lincecum and Madison Bumgarner with San Francisco. Yet Cram is not one to call attention to himself for any degree of credit.

“I’ve never been one (to say that) I did this or I did that,” he said. “Every pitching guy has a chance to touch somebody one way or another, and somewhere along the line some of the stuff sticks and some of it doesn’t. I think we all have a hand in it.”

Most of the pitchers that made up the Giants’ 2010, ’12, and ’14 championship staffs received Cram’s tutelage. “I’ve had most of them,” he said. “The only guy I didn’t have during the season probably would be (Matt) Cain, I only saw him during Instructional League. Actually I was Lincecum’s first professional coach at Salem-Keizer, it was my job just to get him ready to move on and that’s what he did, he moved on.”

He reported no difficulty relating to pitchers just starting out today, despite the changes in the game. “When I mention that when I was in A-ball I completed 14 games, their jaws all drop,” he said.

As a player, Cram always listened to the older pitchers, including Bill Fischer and Gary Blaylock coming up through the minors with the Royals and Koosman and Seaver with the Mets. Those lessons were passed on years later when he became an instructor.

“You pick up all kinds of little things that you learn if you’re listening, like listening to Seaver talk, and (his fellow pitchers) talk about how they’re going to pitch guys, and how they’re gonna pitch ’em with men on base,” he said.

“I guess I was fortunate too; I didn’t spend a lot of time in A ball,” he said. “I spent most of my time in Triple-A, listening to the older guys. I learned a lot by listening and being able to apply some of the things they talked about. Being around Bill Fischer, a real mechanics person, I learned a lot from him, and same thing with Gary Blaylock, I learned a lot from those people. They tutored me well.”

Cram has been married to his second wife, Charlene Guarriello, more than 20 years. They live in Round Hill, Virginia. The 2017 season was his last in baseball, but Cram is proud of what he accomplished in his career. His time in the majors was short, and he never won a game while there. But his overall career, including yeoman’s work in one of the longest games ever and 50 years in professional baseball as either a player or coach, makes Jerry Cram a winner in every sense of the word. Not bad for a walk-on at a tryout camp.

Last revised: February 7, 2019

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgment to Jerry Cram for his memories. All quotes come from the author’s telephone interviews with him on October 16, 2016; December 1, 2016; January 26, 2017; and January 27, 2019.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Notes

1 “Class A Highlights,” The Sporting News, August 5, 1967, 41.

2 Joe McGuff, “Gordon Counts on [Bill] Butler for Quick Royal Service,” The Sporting News, December 7, 1968, 41.

3 Ibid.

4 “Class A Leagues,” The Sporting News, June 21, 1969, 50.

5 “American Association,” The Sporting News, July 19, 1969, 44.

6 Sid Bordman, “Vacancy Sign in Royal Bullpen; Lefty [Jon] Warden Says He’ll Fill It,” The Sporting News, January 17, 1970, 41.

7 “Cram Escapes Jams,” The Sporting News, June 6, 1970, 42. “A.A. Day by Day,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1970, 33.

8 “American Association,” The Sporting News, September 26, 1970, 38.

9 “5 Players Are Thumbed Out in Venezuela,” The Sporting News, January 22, 1972, 47.

10 Eduardo Moncada, “Zulia Pitching Staff Shows Zip Under [Dick] Billings,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1972, 47.

11 Eduardo Moncada, “Rod Carew Latest Casualty in Venezuela,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1972, 55. Besides Cram and Nettles, the others were Chuck Brinkman, Billy Wynne, and Tony Muser.

12 “International League,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1973, 38.

13 “International League,” The Sporting News, September 1, 1973, 32.

14 Jack Lang, “Yogi [Berra], Mets take a ‘Cram Course,” Long Island Press, August 11, 1974.

15 “American Association,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1976, 32.

16 For the second year in a row, Denver won the playoffs in six games.

Full Name

Gerald Allen Cram

Born

December 9, 1947 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.