Sadaharu Oh

“I had reached the point where I simply lived to hit. How can I say it without sounding foolish? I craved hitting a baseball in the way a samurai craved following the Way of the Sword. It was my life.” – Sadaharu Oh, A Zen Way of Baseball (1984)

Easily the most lionized athlete in the history of Japan’s professional national pastime, Sadaharu Oh also owns a leading claim to the title of baseball’s greatest all-time home run slugger. Across a 22-season career with the Central League Yomiuri Giants – Japan’s most celebrated, popular and successful team – the left-handed hitting and throwing first baseman stroked a career total of 868 round-trippers, a number that outstrips those of major league baseball’s most potent long-ball sluggers Barry Bonds (762 in 22 seasons), Hank Aaron (755 in 23 seasons), and original “Sultan of Swat” George Herman “Babe” Ruth (714 in 22 seasons).1 But the claim is certainly not without its controversies and its reasonable challenges. Foremost is the issue of an adequate assessment of the nature and level of Japanese League play during the era of Oh’s productive career; critics point to the lesser quality of Japanese pitching, the size and layout of Japanese ballparks, and the issues surrounding the type of lightweight baseball employed in the Japanese game. But controversies aside, on the basis of raw numbers alone it is indisputable that the charismatic and workaholic Oh produced one of the most impressive career resumes found anywhere that professional baseball has been played at the highest levels.

Easily the most lionized athlete in the history of Japan’s professional national pastime, Sadaharu Oh also owns a leading claim to the title of baseball’s greatest all-time home run slugger. Across a 22-season career with the Central League Yomiuri Giants – Japan’s most celebrated, popular and successful team – the left-handed hitting and throwing first baseman stroked a career total of 868 round-trippers, a number that outstrips those of major league baseball’s most potent long-ball sluggers Barry Bonds (762 in 22 seasons), Hank Aaron (755 in 23 seasons), and original “Sultan of Swat” George Herman “Babe” Ruth (714 in 22 seasons).1 But the claim is certainly not without its controversies and its reasonable challenges. Foremost is the issue of an adequate assessment of the nature and level of Japanese League play during the era of Oh’s productive career; critics point to the lesser quality of Japanese pitching, the size and layout of Japanese ballparks, and the issues surrounding the type of lightweight baseball employed in the Japanese game. But controversies aside, on the basis of raw numbers alone it is indisputable that the charismatic and workaholic Oh produced one of the most impressive career resumes found anywhere that professional baseball has been played at the highest levels.

The differences between Japanese and North American major league baseball left aside for the moment, Oh’s numbers stack up quite impressively against those of his three main rivals for the title of supreme slugger – Aaron, Bonds and Ruth. With 3,000-plus fewer at-bats than Aaron (his seasons were 14-32 games shorter) Oh still managed 100-plus more round-trippers; and with only 2,786 total career hits, nearly a third of his safeties actually left the ballpark. His AB/HR ratio is the best of the quartet (a homer every 10.7 official ABs, compared to 11.8 for Ruth, 12.9 for Bonds and 16.4 for Aaron). Oh also claims the best walks-to-strikeouts ratio (he walked 1071 more times than he struck out, slightly ahead of Bonds’ 1019 positive ledger in walks versus strikeouts). And his 13 consecutive home run crowns in the Central League (15 in total) have no parallel in the majors. Many would of course claim that Bonds should be dropped from the comparison altogether, given that the bulk of his long-ball numbers were achieved in a recent “Steroid Era” tainted by acknowledged reliance on performance-enhancing medications.

The remarkable story of Oh’s four-decade career (as both player and manager) is, however, a saga that stretches far beyond mere raw numbers and record-book batting feats. Comparisons with big leaguers or idle speculations over Cooperstown status miss out on the appreciation of unprecedented athletic accomplishments taken in their own context and thus only tend to reveal the frequent parochialism inherent in many North American discussions of the bat and ball sport. Sadaharu Oh’s arduous rise to prominence in the Japanese League and the unparalleled longevity of his topflight performances contain the saga of one of the most dedicated and tenaciously serious pro athletes the sport has ever produced; Oh’s physical dedication and tenacity stand far above the crowd even within a Japanese-style of baseball play famed for its slavish devotion to physical training and mental discipline. Nothing came especially easy for the self-made slugger – from the first physical and emotional setbacks of his earliest schoolboy career; to the difficult transitions, unfulfilled potential and accompanying frustrations of his first four professional seasons; to the late-career pursuits of distant landmarks owned by Ruth and Aaron – and thus the story of Oh’s career development is one of the most inspiring personal tales found anywhere in the world of sport.

Not to be entirely overlooked in any portrait or career summary of Japan’s greatest ballplayer is the rather substantial fact that Oh is also the co-author (with American journalist David Falkner) of one of the most remarkable ballplayer biographies ever published. In that volume Oh not only provides readers with one of the fullest understandings of the special nature of baseball in Japan; at the same time he also offers one of the most honest and revealing self-portraits ever penned by a former professional athlete. One recent online reviewer looking back on the volume published nearly 30 years ago (in 1984) adequately describes A Zen Way of Baseball as “not strictly an autobiography [but instead] more the story of an idea and a process.”2 Oh writes with great sensitivity about the triumphs and failures of his remarkable life, both on and off the baseball diamond. But most of the book’s ink is focused on his intimate relationship with hitting coach and personal spiritual guru Hiroshi Arakawa and their lengthy joint struggle to master an approach to hitting a baseball based on stoic mental discipline and grounded in the dedicated practice of rituals drawn from traditional Zen and Aikido philosophy. Oh lays out the personal failures and triumphs of his career in a most eloquent and humble manner, one entirely devoid of the self-aggrandizement found at the heart of most personal reminiscences penned by ex-athletes. The engaging self-portrait is thus both emotion-packed and gripping from start to finish.

A great irony surrounding Oh’s storied baseball tenure is the fact that while he would eventually become the most widely known and celebrated product in a baseball-crazy Asian nation – the only universally recognized Japanese ballplayer within the game’s epicenter in North America and the Caribbean – nonetheless he was for most of his career never the most popular player in his own homeland or even on his own celebrated Tokyo Giants team. That honor seemingly always fell to Yomiuri Giants teammate Shigeo Nagashima, a beloved third baseman whose own slugging feats stood only a shade behind Oh’s.3 Nagashima broke into the Central League one year ahead of Oh but retired a half-dozen seasons earlier, serving as Giants manager across Oh’s own final six campaigns. Together Oh and Nagashima were known far and wide in Japanese baseball lore of the 1960s and 1970s as the ON Hou (the Oh-Nagashima Cannon) and their presence in the same lineup made the Yomiuri ball club the most dominant in Japanese League history. But it was always Nagashima that seemingly attracted the highest devotion among Japanese fans (and a wide majority of Japanese fans were dedicated Yomiuri Giants rooters, whether they lived in the capital city of Tokyo or elsewhere in the Japanese islands). Writing during Nagashima’s Tokyo managerial tenure, renowned Japanese baseball commentator Robert Whiting (perhaps the English-language author most responsible for the popular notion of Oh’s second-tier status) went so far as to suggest that the star third baseman was “the best loved, most admired, and most talked about figure in the history of sport … the adulation accorded to Nagashima [even being] unequalled by Babe Ruth’s fans in his years with the Yankees.”4

The reason for differing hometown reactions to Nagashima and Oh – to whatever degree they actually existed – seemingly had at least something to do with the strong racial prejudice and jingoism which has long been a central feature of Japanese cultural and social life. Not to be pure-blooded Japanese carries a heavy social stigma in the island nation and Sadaharu Oh – like many other top Japanese League stars down through the years – was widely known to be of foreign ancestry. Fiercely proud of their native baseball traditions, Japanese fans and ballplayers alike often made life difficult for American imports (especially ex-big-leaguers) when they began to arrive on the scene in the 1950s and 1960s and the “Gaijin” phenomenon has long been one of the defining staples of professional baseball played Samurai style.5 And while the label of unwelcomed “Gaijin” (literally “foreigner”) stuck fast to virtually all American imports – both surly and uncooperative underperformers like Joe Pepitone and Don Newcombe, and also more quickly acculturated high-level performers like Daryl Spencer, George Altman and Clete Boyer – it also discolored the Nippon league careers of such Japanese-raised stars as Russian-born pitching nonpareil Victor Starffin and Hawaiian-born American Nisei Wally Yonamine. And many Japanese-born natives owning Korean or Taiwanese roots have been forced to hide (as much as possible) their non-Japanese ancestry in order to maintain respectable professional careers on Central League and Pacific League diamonds in the Land of the Rising Sun.

The future baseball star and national idol arrived in the most humble of circumstances, being born (with twin sister Hiroko) in the Sumida district of war-torn Tokyo during May of 1940, the second son of an immigrant Chinese father (Shifuku) and a native Japanese mother (Tomi).6 His birth date is today widely published as May 20, 1940, but the actual date (as reported by Oh himself in his celebrated autobiography) was in fact ten days earlier on May 10.7 Oh’s parents were working class shop keepers with little formal education and at the time of his birth they ran a small Chinese noodle restaurant in Tokyo’s Asakusa neighborhood. Shifuku originally hailed from the Zhejiang Province of mainland China and carried a PRC (Communist China) passport throughout his own life span in his adopted homeland. But worried about the eventual fate of the two separate Chinas at the close of the Second World War, Shifuku eventually obtained ROC (Taiwanese) passports for each of his sons. While Sadaharu would grow up speaking only Japanese and also displaying thoroughly Japanese orientations in his cultural attitudes, he would maintain his ROC passport throughout his adult life as a sign of paternal respect as well as permanent tribute to his own ethnic heritage. It would nonetheless be a heritage that would have considerable negative impact on the future ballplayer’s widespread perception as a “foreigner” (or Gaijin) posing as one of Japan’s greatest popular culture heroes.

Oh’s original Chinese name of Wang Chenchih holds a somewhat ironic meaning once translated into its Japanese equivalent (meaning roughly “emperor” or “king”); the rather strange-sounding “Oh” was simply the Japanese pronunciation of the common Chinese surname Wang. Oh would later find much significance in the fact that he was actually born as a twin and that the sister with whom he shared his birth would die only fifteen months later. He would write in the opening pages of his autobiography about the strange sense he has always felt that he somehow carried two lives and two personalities within his single being and that his strengths (physical, mental and spiritual) in later life were thus not merely his own exclusive property. He would also in those same pages explain that although he was born left-handed (a later strength in his baseball career) he grew up as a young child believing he was right-handed, due to the popular practice at the time of suppressing left-handedness which was traditionally considered an evil omen and even a vile curse. Fortunately, although trained to write and use chopsticks with his right hand, an innate left-handedness could not be suppressed permanently on the athletic field.

The future ballplayer’s earliest years were filled with the considerable hardships suffered by all urban Tokyoites during and immediately after the horrific years of World War II. His father was arrested and imprisoned for several months, purportedly under suspicion of being a foreign spy, but more likely simply because he was Chinese and also because he aggravated local officials by keeping his noodle restaurant open beyond wartime curfew hours. Oh’s first childhood memories include being carried on his mother’s back as they fled their devastated neighborhood during the fire bombings that destroyed most of urban Tokyo.

It was older brother Tetsushiro (ten years the senior) who would play a major role in developing young Oh as a talented baseball player and also inspiring early-formed and deep-seated love for the popular Japanese national game. Tetsushiro was charged with babysitting his younger sibling while both parents daily manned the family business and thus would regularly drag him along to the local sandlot games in which Tetsushiro honed his own skills. Soon enough Sadaharu was also enthralled with playing the game, at first swinging from the right side of the plate like all the other boys since he assumed that was part of the fixed rules of the game. As with so many future professional ballplayers, however, young Oh had to overcome some deep-rooted objections of his immigrant father toward idle ball-playing; Shifuku envisioned his sons pursuing some more respectable occupation of the kind envisioned by any lower-class immigrant parent aspiring to middle-class financial success for his own offspring. His dream was that one son might become a medical doctor and the other an electrical engineer. Tetsushiro as eldest sibling would please his father greatly when he entered Keio University as a medical student when Sadaharu was still only in the fourth grade of primary school.

Tetsushiro’s abiding love for baseball would in the end, however, work to defeat a father’s more prosaic ambitions for the younger of the two offspring. He not only included his brother in local neighborhood ballgames (where Sadaharu displayed an early talent as a pitcher while still in elementary school) but also planned outings to Korakuen Stadium where Sadaharu would first thrill to the play of the popular Yomiuri Giants and watch the exploits of such early post-war era stars as 400-game-winner Masaichi Kaneda, Hanshin Tigers slugger Fumio Fujimura, and Giants’ hitting wizard Tetsuharu Kawakami. Tetsushiro’s own playing would be suddenly derailed by a career-ending injury when he broke an ankle in a neighborhood league game while still a medical student at Keio. But his role as inspiration for his more talented and fortune-blessed brother would indeed have an immense future impact on Japan’s national sport and consequently also on the nation’s soon thriving post-war popular culture.

Horrified that his elder son’s injury and resulting hospitalization came on the eve of the boy’s crucial university medical examinations, Shifuku forbade any further ball-playing by either of his offspring. As the dutiful and respectful elder son, Tetsushiro pledged to abandon the sport but Sadaharu (while quietly nodding his own agreement to his father’s demand) continued to indulge his baseball passion as much as possible out of the senior Oh’s sight. Since his popular junior high school baseball team boasted a long waiting list for enrollment of any new aspiring players, Sadaharu was forced to perform on a collection of local neighborhood sandlot clubs, including a squad of much older university medical students that had been organized by his brother. The first taste of true baseball success for Sadaharu would eventually come as a high school pitching star at one of Japan’s most celebrated secondary-school baseball factories. But even getting to attend the prestigious Waseda Commercial high school took some effort since it was accomplished only against the strong initial objections of Oh’s practical-thinking and stubborn father.

Resigned to follow his brother’s footsteps and honor a father’s long-standing wishes, the young Oh was prepared for dropping baseball as a career option and pursuing an engineering career. But fate intervened and charged his life’s course when he failed to score high enough on entrance examinations that would have admitted him to the Sumidagawa Public School for a pre-college course of studies. He had, however, been accepted to the Waseda Jitsugyo (Commercial) campus and a visit to the baseball facilities at Waseda arranged by a local sporting goods dealer quickly awoke renewed dreams of pursuing baseball as more than an idle hobby. Shifuku of course strongly objected to any such plan, but eventual gentle if forceful persuasion from Sadaharu’s brother and uncle turned the tide. Sadaharu reports in his autobiography that his fortunes took a fateful and perhaps destined turn when Shifuku Oh was finally convinced by Tetsushiro that perhaps it would be okay to “let there be one strange profession” in the Oh family.8

High school baseball in Japan – today as well as during the decade of Oh’s youth – is not at all similar to the North American high school sport. A far better comparison might be made with top-level college football or basketball, but even that does not quite do the Japanese version of the scholastic game full justice. An annual spring national high school championship tournament staged at Koshien Stadium in Osaka has for decades now been a centerpiece of Japan’s baseball fanaticism. Upwards of a half-million spectators pass through the turnstiles for the ten-day event and national television provides day-long coverage of the games. The fascination with schoolboy baseball spills over to the collegiate ranks as well and Tokyo’s Big Six University League draws nearly as much attention as the celebrated professional Yomiuri Giants. Robert Whiting reports in the late-1970s that Big Six games between traditional rivals Keio and Waseda universities would “for sheer spectacle [surpass] a Michigan-Ohio State football game.”9

Oh began his career as a celebrated schoolboy pitcher, although he also displayed early talent as a powerful batsman. By the time his freshman season commenced at Waseda he was already swinging from the left side of the plate, a practice he had taken up more than a year earlier when he was told by pro outfielder Hiroshi Arakawa that as a natural southpaw he was wasting his talent by swinging from the right side in imitation of his teammates. The fortuitous meeting with Arakawa (Oh’s future batting instructor and spiritual guru) took place in November 1954 when the big leaguer had by chance stopped to watch a sandlot practice game in which the 14-year-old was playing. But as a high school rookie several months later it was young Oh’s work on the mound that drew most public attention. As the Waseda squad’s number two pitcher he hurled a no-hit, no-run masterpiece in an early round of the national playoffs designed to determine qualifiers for the summer’s prestigious Koshien tournament. He also smashed a homer in the final game of that preliminary event which launched his squad into the Osaka-based Koshien championships.

While the first year of Oh’s high school career would experience a number of such celebrated moments of triumph it would also own its full share of painful episodes involving defeat and disappointment. The first such setback came in an early-season tournament match with an arch rival school which Waseda defeated 4-0 on the strength of a complete-game shutout tossed by Sadaharu (who was still a week short of his sixteenth birthday). But celebration was quickly transformed into sadness when Tetsushiro delivered a devastating post-game tongue lashing. The stinging post-game rebuke Oh received from his brother (for showing up his defeated opponents by tossing his glove in the air in unbridled celebration) made such a deep impression on the young athlete that it firmly fixed his resolve to forever hide his emotions on the field of play, a practice that would continue across the next quarter-century of his budding baseball career.

An even deeper disappointment came at season’s end when starter Sadaharu Oh completely lost control of his pitching mastery in the second contest of the Osaka Koshien tournament. Unable to locate the plate Oh was quickly removed from the game and Waseda consequently received a severe drubbing that sent them heading home from Osaka after only two outings. This sudden attack of pitching wildness had also occurred several times earlier in the season and Oh’s coaches would quickly conclude that perhaps inadequate body balance and a faulty pitching rhythm were the true culprits. They also speculated that a solution might be found in developing a novel no-wind-up delivery. By the end of that 1956 fall high school season Oh had become the first pitcher in Japan to experiment with the then-novel no-wind-up pitching style. Ironically Oh adopted the unique pitching approach in precisely the same month that Don Larsen of the New York Yankees employed identical mechanics while pitching the first-ever no-hitter and perfect game in the history of the North American major league World Series.

At the outset of Oh’s sophomore high school season his Waseda club returned to Osaka for the spring version of the Koshien tournament. Unlike the summer Koshien event which required qualification, the spring version was an invitational affair involving only a couple dozen schools. 10

Despite brighter prospects for Waseda this time around, the second Koshien trip would again involve a tantalizing mixture of challenging pain and pride-filled triumph for the promising young pitcher. Oh had developed severe blisters on the fingers of his pitching hand during the intensive training sessions leading up to the tournament and although he successfully completed his first couple of starts (he was now on the mound for all his team’s tournament games) he also struggled against destracting pain in the damaged digits that made it most difficult for him to grip the baseball let alone heave it at top speed. Despite increasing pain, a bloody baseball, and the need to rub dirt into his torn fingertips after each pitch, Oh agonized most severely not over his physical discomfort but rather over the fear that he would have to reveal his hidden ailment to his teammates, or that he might be responsible for yet another team failure at Koshien. Watching the games on television back in Tokyo Shifuku miraculously somehow sensed his son’s problems and made a surprise 700-mile round trip to Osaka bringing a traditional Chinese folk ginseng-root remedy that quickly relieved Sadararu’s suffering. With his father’s unexpected but deeply appreciate aid Oh was ultimately able to struggle through the nine innings of the final game in which Waseda was this time crowned as Koshien champions.

Oh’s Waseda high school career would also involve one additional deeply painful personal defeat – one that underscored the exclusion and prejudice he would continually experience has a non-pure-blood Japanese resident of Chinese ancestry. On the heels of the victory in Koshien the Waseda club was selected for a second invitational tournament, this time the Kokutai or National Amateur Athletic Competition to be staged in Shizuoka Prefecture. But this national competition was specified as open to native Japanese athletes only and as a result the star Waseda pitcher was informed that he could not take part alongside his teammates. Deep disappointment was soothed only by the solidarity displayed by teammates and coaches who insisted that their banned star hurler don his uniform and travel with the team even though he could not take to the field to compete. It was this event that Oh would later remember as a cherished symbol of the deep-seated spirit and camaraderie inherent in Japanese high school baseball.11

Sadaharu’s high school club would not make it back to Koshien at the conclusion of his final season; they would instead suffer a year-end heartbreaking defeat against their top rivals from Meiji that ended their season (and Koshien qualification hopes) with what Oh remembered as his toughest defeat during a lifetime of playing baseball. Oh was on the mound to surrender the game-winning hit that capped a miraculous Meiji five-run rally in the bottom of the twelfth. But that final schoolboy defeat was quickly enough washed away when dreams of a future baseball career loomed on the horizon. Later that same winter the heavily recruited youngster rejected an opportunity to pursue college play at nearby Waseda University and then also turned down a contract offer to sign with the Central League Hanshin Tigers. He opted instead to ink a contract with the Yomiuri Giants, the beloved hometown team he had followed passionately throughout his childhood. The proffered first-year Giants contract specified a hefty rookie salary of 13 million yen (about $60,000 US).

Despite the optimisms surrounding such a hefty investment in an untried rookie, Sadaharu’s earliest seasons as a Yomiuri Giant were marked mostly by failure and frustration as he struggled to make the transition from amateur to professional-level competition. It was almost immediately determined that his future promise lay in his considerable promise as a strong batter and not as an undersized pitcher, and by the time spring training concluded before his 1959 rookie season he had settled into the starting lineup as a first base replacement for the legendary “God of Batting” Tetsuharu Kawakami, a longtime all-star who had recently retired to become the Giants hitting coach. But such early votes of confident from manager Shigeru Mizuhara (in his final Giants season) bore very little immediate reward.

Oh’s early seasons (especially a rookie campaign that produced a mere .161 batting average over 94 games) were marred by a technical weakness in the youngster’s approach to swinging a bat that had remained largely unnoticed during triumphs as a high school star but quickly became a fatal flaw for the struggling pro. Kawakami worked long and patient hours with his young disciple to correct improperly rigid leg and hip movements that were causing Oh to pull his head up and his eyes off the ball; the defect left him particularly vulnerable to breaking balls and any pitches tossed by left-handed hurlers. The St. Louis Cardinals had paid an late fall exhibition visit (October 24-November 15, 1958) to Japan and the following spring the struggling nineteen-year-old Giants rookie attempted briefly and quite unsuccessfully to experiment with Stan Musial’s renowned contorted batting posture. That failed adjustment was quickly dropped. In his debut Central League game Oh struck out twice and didn’t put a single ball in play; through his first 13 games and 26 at-bats he went hitless until the string was broken by his first big league hit (a “Chinese” homer that barely topped the fence and was hit off an old high school rival, Genichi Murata, who was now pitching for the Hanshin Tigers).12

As Oh’s struggles persisted and as strikeout totals continued to mount (he ended the season with 72 in but 193 ABs, more than one for every three official plate appearances) hometown fans began publicly mocking his Chinese name (literally translated as “King”); during each plate appearance in jam-packed Korakuen Stadium many in the throng would loudly chant “Oh! Oh! Sanshin Oh!” (“King! King! Strikeout King!”). And to make matters even worse, this was also a time when Oh was perhaps less than totally serious about his dedication to the game. He received further stinging criticism from coaches and the press alike for his newly developed habit of post-curfew partying, heavy after-hours drinking, and lavish spending in Tokyo’s Ginza bar district.

It was early in his career and in the midst of his struggles to find some degree of hitting success that Oh played a significant role in what is still celebrated a half-century later as the most famous game in Japanese professional baseball history. This was the now-legendary “Emperor’s Game” (June 25, 1959) that would write the name of Shigeo Nagashima indelibly in the island nation’s celebrated baseball lore. The Japanese Emperor (Hirohito) and Empress (Kojun) attended their first-ever baseball game that day at Korakuen Stadium to witness a match between the Giants and visiting Hanshin Tigers. Coming off his rookie-of-the-year 1958 debut season Nagashima was already an established Yomiuri star and didn’t disappoint on this most historic occasion; his fifth-inning homer gave the popular home team a brief lead. After the Tigers had again seized the advantage, promising rookie Oh belted a seventh-inning round-tripper of his own (one of only 7 he hit all season) to again equalize the affair. Scheduled to depart the stadium at 9:30 pm, the royal couple remained in their seats to watch one final at-bat by star slugger Nagashima in the home ninth. A storybook ending unfolded when Nagashima drove a pitch from ace hurler Minoru Murayama into the left-field seats for the most celebrated sayonara home run of Japanese league history. All remember that Nagashima stroked the most legendary round tripper in national lore on that memorable day; few recall that it was rookie Sadaharu Oh who had set the stage for Nagashima’s indelible heroics.

Perhaps the single element that best defines the career of Japan’s greatest slugger was his unique approach to batting and the unparalleled batting stance and swing that would become a calling card during the most productive middle and late years of his career. Of course there have been a fair share of big league batsmen also known for odd approaches to the art of batting a thrown ball and equally renowned for their strange yet effective stances at the plate. There was Ty Cobb with his famed split-hands grip designed to increase bat control in an age of “small-ball” slap hitting. There was Stan Musial and his corkscrew position in the batter’s box that was the closest parallel perhaps to the stance that later defined Oh. There was Gil McDougald with his oddly dropped bat (the top end of his war club nearly touching the dirt at the rear of the batter’s box) and also Mel Ott (another parallel for Oh) with his raised leg accompanying an unorthodox and seemingly off-balanced swing. There has never been only one approach to successfully stroking a spherical ball with a round stick of lumber.

But Oh’s approach was easily the most unusual of all and one that involved great physical discipline to fully master. The batting posture that came to define the unique hitting approach of the Giants’ top young prospect appeared in his fourth pro season and was the outgrowth of a lengthy struggle to overcome a failure in technique that had marred his three earliest campaigns. It was also the result of a long period of tutoring (approximately two years) under the wing of former Japanese big leaguer Hiroshi Arakawa. In his masterful autobiography (Chapters Six and Seven) Oh details at great lengths the origin and development of his hitting style, as well as the near-career-long relationship with his own personal batting guru.

Oh’s first fateful meeting with Arakawa had been that brief chance encounter at a local sandlot game which had prompted him to first adopt a better hitting strategy as a natural left-handed swinger. A still more fortuitous and career-changing reunion came at the outset of the 1962 season (Oh’s fourth with the Giants) when Kawakami succeeded Shigeru Mizuhara as manager and inked Arakawa as the club’s new hitting coach. Arakawa was a devoted student of Zen philosophies as well as a former outfielder with the Mainichi Orions (his best season was 1954 when he hit at a .270 clip) and had employed his Zen studies and practices to improve his own hitting techniques during a mildly successful nine-season Pacific League career. It was Arakawa-san who first concluded that Oh’s primary difficulty was not so much the earlier troubling tight hip problem but a severe “hitch” in his swing and that the solution to correct the flaw might well be Arakawa’s own favored approach based on “down swinging” and not “upper cutting” the pitched baseball. The pair began a lengthy teacher-disciple relationship that would last until Arakawa signed on in 1974 to manage the rival Central League Yakult Swallows.

The struggle to correct Oh’s early-career batting weaknesses became a lengthy and arduous one and that personal battle represented the most difficult sustained period of the slugger’s otherwise success-draped career. To combat the debilitating and ingrained “hitch” Oh (under Arakawa’s careful tutelage) developed a seemingly awkward approach at the plate that involved balancing himself on his left leg, with the right leg lifted off the ground and the tip of his bat tilted toward the pitcher to maintain the necessary perfect balance. It was an approach Oh would perfect not only through hours of “shadow swings” in front of a full-length mirror about also with the painstaking study of ancient Aikido philosophy (in the pursuit of perfecting his single-leg “balance”) as well as several years of disciplined exercises swinging a Samurai sword. The eventual remarkable success of his new “flamingo” stance (Oh’s own name for the approach) is today the stuff of Japanese baseball lore. And the connection with a Japanese tradition of Samurai warrior swordsmanship is a major part of the fairy tale-like story.13 The immediate results were two breakout seasons (1962 and 1963) that produced the first two of an unparalleled 13 consecutive home run titles. And several days after Oh smashed his first “flamingo” style home run in Korakuen Stadium (versus the Hanshin Tigers) Arakawa issued a surprising challenge to his rapidly improving pupil when he suggested that they now set their sights squarely on overhauling Babe Ruth’s long-established and iconoclastic big league home run record. It seems that Arakawa may not only have been a master teacher but also something of a miraculous Zen soothsayer.

The 1964 campaign marked Oh’s arrival as Japan’s greatest slugger. It was also the year that he would indisputably seize the reins from Nagashima as the Giants’ most potent offensive weapon. Benefitting from the use of handmade tamo-wood bats fashioned for him by a master craftsman named Jun Ishii, Oh went on a slugging rampage in 1964 that produced a still-record 55 homers and included an early May four-homer explosion against the Hanshin Tigers in Korakuen Stadium. Two days after that record one-day outburst a new wrinkle entered the unfolding Oh saga when the visiting Hiroshima Carp introduced a new defensive strategy that would become known as the “Oh Shift” and would replicate the defensive alignments first conceived in 1946 for use against Boston Red Sox slugger and dead-pull-hitter Ted Williams by Cleveland Indians manager Lou Boudreau. The alignment employed by Hiroshima against Oh (the entire left side of the field left open with the third baseman standing behind second base) was slightly more extreme than the famed American League “Williams Shift” (which had the left fielder positioned about 30 feet beyond the infield in short left-center). But the object was the same and Oh’s reaction paralleled that of Williams. He refused to take easy base hits (and thus perhaps batting .400 or more) by slicing the ball toward the opposite field. The reason in this case was that to stop pulling the ball would have meant giving up on his new stance and hitting style – the very psychological effect that Hiroshima (and later other teams) most obviously had in mind.

Once Oh found his stride and his unorthodox stroke in his fourth pro season he never looked back. Few players (big leaguers, minor leaguers, or otherwise) have ever enjoyed so heady and long a run of unrivaled successes. His initial Central League home run title in 1962 (with 38, bettering by one the total of his first three campaigns combined) was the first of an unparalleled 13 straight and 15 in the following 16 years. He would pace the circuit in walks for 18 straight years (and in all but four of his total career seasons). He was a Central League batting champion five times (three consecutively during 1968-1970) and an RBI king on 13 different occasions, with strings of four straight seasons (1964-1967) and later eight straight (1971-1978). He paced the Central League in total base hits on only three occasions but in total runs scored on 15 (13 consecutively, 1962-1974). There were also a pair of Triple Crowns (1973, 1974) thrown into the mix. For two full decades Oh-san (Mr. Oh) literally owned the Japanese baseball record book when it came to all phases of successful and even masterful power hitting.

Late career years were surrounded by the ultimate pursuit of Babe Ruth’s once seemingly invincible career mark of 714 big league dingers. The challenge presented early on by Guru Hiroshi Arakawa was no longer an impossible dream by the time the 1976 season rolled around. Milestone home run 500 had come on June 6, 1972 in Hiroshima; number 600 (the first time a Japanese leaguer had reached that plateau) came in the midst of his second Triple Crown year (May 1974) and was struck against the Hanshin Tigers at Koshien Stadium. Despite a 648-game playing streak coming to an end in 1975, Oh charged on and the magic number 700 was finally reached on July 23, 1976 in Kawasaki versus the Taiyo Whales (ironically in the same stadium where Oh had debuted his “flamingo” stance back in 1964). Ruth was finally overhauled on October 11 of that same season (only four games from the end of the campaign) and if there was any disappointment attached to the historic event it was only the fact that Hank Aaron had already crossed the big-league milestone in Atlanta two full seasons earlier (on April 8, 1974).

With Ruth in the rearview mirror, next came the struggle to surpass Hank Aaron who had also bypassed the Babe’s once-cherished record far ahead of his Japanese rival. Oh and new big league record holder Aaron would actually meet in Tokyo’s Korakuen Stadium in November 1974 for a head-to-head slugging showdown celebrated all across Japan even if largely ignored by North American fans. With 50,000 fanatics in attendance for the event, the pair alternated five fair-ball swings each for four rounds and Aaron game out the winner with 10 successful long balls in his allotted 20 swings; Oh socked nine out of the park in fair territory. By the time Oh had reached and surpassed Ruth at the end of the 1976 campaign, Aaron was already announcing his own retirement after ringing up a final 755 career total. Oh would himself surpass that mark (off a delivery from Yakult Swallows hurler Yasujiro Suzuki) on September 3, 1977 before a wild overflow home crowd in Korakuen Stadium. With Aaron finally conquered, the quest continued and new goals were set, although Oh admits those later milestones never had quite the same allure. Home run number 800 was struck late in the 1978 season, but the final goal of 900 would never be reached before Oh finally retired at the conclusion of 22 campaigns in November 1980. Oh later wrote that he was saddened by Aaron’s earlier 1976 retirement and thus the end of their ongoing head-to-head long-distance competition.

Oh’s career in the end produced nine Central League MVP awards, four in the 1960s, five more in the 1970s and in the end also four more than his more fan-favored long-time teammate Shigeo Nagashima. But the many team successes earned by the O-N Cannon Giants (as the team was popularly known) were even more numerous and totaled 11 Japanese Series titles during Oh’s two-decade-plus career. In brief, he celebrated as a Japan Series winner (Japan’s World Series) in a full half of his league seasons as an active player. A comparable achievement would be Joe DiMaggio’s collection of nine World Series Titles in only 13 career seasons with the Yankees, although DiMaggio’s successes admittedly came over a much shorter career span. But by the second half of the seventies Oh found his slugging powers waning and perhaps an earlier retirement might have left his record of team championships looking far more like that enjoyed by DiMaggio and the Yankees. Oh’s last Japan Series victory came in 1973 (although his club did reach the final playoffs in both 1976 and 1977, only to lose on both occasions to the Hankyu Braves). But the personal drive for home run records would be sufficient to stretch Oh’s career several years beyond its prime. He still slugged 30 homers in his final season at age 40 but only managed to post an anemic batting average that dipped slightly below the .240 standard.

The loss of his headlining role as celebrated active player hardly meant the close of Oh’s five-decade career on the baseball diamond. He quickly threw himself into the next stage as a high-profile coach (assistant manager) with his beloved Giants; he also built a new home which fittingly contained an old-style training room with tatami mats just like the one in which he had trained under Atakawi. He would serve as the assistant skipper of his old club for three full seasons under new bench boss Motoshi Fujita (who had replaced Nagashima); in that span the club captured one Japan Series, won two Central League pennants, and limped home in second place on the third occasion.

In 1984 Oh moved into the top slot as Yomiuri Giants field manager, a position he would hold for a short span of only five moderately successful seasons. The skein would produce a single Central League championship banner in 1987 (but also a six-game loss in the Japan Series to the Seibu Lions). Oh’s tenure also featured an overall .568 winning percentage, two second-place finishes, and another pair of seasons in third slot. He would later manage the Fukuoka Daiei (later SoftBank) Hawks (beginning in 1995) where he enjoyed even greater pennant successes, achieving three Pacific League titles (1999, 2000 and 2003) and twice reigning as Japan Series champion. After his managerial career was briefly interrupted by the life-threatening 2006 bout with cancer, Oh reclaimed his spot on the Fukuoka bench for a single swansong 2008 Pacific League season, his final team finishing in the league cellar more than a dozen games off the pace. After retirement as an active field boss Oh would serve two additional seasons as the Hawks front office general manager. Over 19 campaigns as an active Japanese League manager the final ledger for the former home run king would read 2501 total games, 1345 wins, 1141 losses, and an impressive overall .541 winning percentage.

In 1984 Oh moved into the top slot as Yomiuri Giants field manager, a position he would hold for a short span of only five moderately successful seasons. The skein would produce a single Central League championship banner in 1987 (but also a six-game loss in the Japan Series to the Seibu Lions). Oh’s tenure also featured an overall .568 winning percentage, two second-place finishes, and another pair of seasons in third slot. He would later manage the Fukuoka Daiei (later SoftBank) Hawks (beginning in 1995) where he enjoyed even greater pennant successes, achieving three Pacific League titles (1999, 2000 and 2003) and twice reigning as Japan Series champion. After his managerial career was briefly interrupted by the life-threatening 2006 bout with cancer, Oh reclaimed his spot on the Fukuoka bench for a single swansong 2008 Pacific League season, his final team finishing in the league cellar more than a dozen games off the pace. After retirement as an active field boss Oh would serve two additional seasons as the Hawks front office general manager. Over 19 campaigns as an active Japanese League manager the final ledger for the former home run king would read 2501 total games, 1345 wins, 1141 losses, and an impressive overall .541 winning percentage.

Sadaharu Oh’s most prestigious stint as a field manager was perhaps his most successful and easily his best known – at least to fans outside of Japan. Appointed skipper for the inaugural showcase MLB World Baseball Classic in March 2006, Oh led his nation’s team to a dramatic Gold Medal victory over the upstart Cubans (the only serious contender without any big league players on its roster). The Oh-led Nippon squad featured such current or future MLB notables as pitchers Daisuke Matsuzaka, Hiroki Kuroda and Akinori Otsuka, plus Seattle Mariners stalwart Ichiro Suzuki, yet the team nonetheless struggled early on, losing an opening-round match with rival Korea in the Tokyo Dome and only advancing to the San Diego finals on the strength of a single controversial round-two win over Team USA and a resulting complicated tie-breaker scenario. In the final wild shootout at PETCO Park, however, Oh’s forces up-ended the Koreans 6-0 in a rain-drenched semifinal and then outlasted Cuba 10-6 mainly on the strength of four-run outburst in both the first and ninth innings.

Oh’s managerial career would not be without its controversies, especially the three instances (one with the Giants and two during his tenure with the SoftBank Hawks) involving a trio of serious challenges to his single-season home run record launched by foreign-born “Gaijin” imports. The events were all-too reminiscent of earlier situations in which Japanese pitchers thwarted potential Gaijin home run or batting crowns by pitching around Americans Daryl Spencer (1965), Dave Roberts (1969) and George Altman (1971). The first incident involving Oh came in 1985 when American Randy Bass (Hanshin Tigers) entered the season’s final game versus Oh’s Giants only a single blast short of Oh’s cherished 1964 record; Bass received four straight walks on four wide pitches each. In 2001 Tuffy (Karl) Rhodes (Kintetsu Buffaloes) had already tied the long-standing mark with seven full games remaining on the schedule; but Rhodes received the same treatment and same assortment of unhittable wide tosses during a final weekend series with the Oh-managed Hawks. Finally, in 2002 Venezuelan Alex Cabrera had again equaled the standard with five games remaining; again he was walked repeatedly in the season-ending set of games versus Fukuoka. In each case Oh denied ordering his pitchers to conspire against the challengers, and there is even evidence that he actually ordered his staff to throw hittable strikes to Cabrera. Whatever Oh’s own direct involvement in the apparent conspiracies might have actually been can only now remain a matter of pure speculation.

Early in his budding professional baseball career Oh had married Kyoko Koyae to whom (along with mentor Arakawa) his impressive 1985 autobiography would later be dedicated. He had known Kyoko originally as a starry-eyed autograph seeker he had met during his rookie campaign with the Giants and he was immediate struck by her beauty as well as her practical intelligence; he was also impressed by the fact that she wrote him repeated insightful letters for several years even though she wasn’t even a true baseball fan. The long-term correspondence carried on for more than half a decade before the pair was finally officially married a full seven years later. The couple had three children, all daughters.14 Kyoto would die at age 57 (in December 2001) from stomach cancer, the same disease that would eventually slow but not fell Oh himself in mid-2006. Less than one year after her death Kyoko’s ashes were sadly and quite mysteriously stolen from the family grave site in Tokyo.

Sadaharu himself would later suffer from the same disease (he was diagnosed only a few months after Japan’s victory in the inaugural WBC) and, although he recovered fully, the brief bout with cancer did keep him from repeating his managerial role with Team Japan during the 2009 second edition of the World Baseball Classic.15 The Nippon squad under new skipper Tatsunori Hara (Yomiuri Giants manager) nonetheless claimed its second consecutive WBC championship, with Oh personally attending many of his former club’s 2009 WBC games during his lengthy ongoing post-surgery rehabilitation. He would also again be a notable presence at the third edition of the WBC in March 2013 when he threw out the ceremonial first pitch to open initial tournament round robin action in Fukuoka’s Yahoo Dome.

Post-career years also provided a number of non-baseball awards befitting a national hero. Oh was named an Ambassador-at-Large to the Republic of China in 2001 by Taiwanese president Chen Shui-ban, with an official charge of promoting sports exchanges between Japan and Taiwan. Eight years later (February 2009) he also received the prestigious Taiwanese Order of Brilliant Star from the then-president Ma Ying-jeou (a decoration he would subsequent refer to as “the greatest honor of my life”). The supreme lasting tribute to Oh, however, is the extensive Sadaharu Oh Museum today housed at the Yahoo Dome Stadium in his adopted home city of Fukuoka. This museum is easily the most extensive, most impressive and most complete shrine dedicated to a single ballplayer to be found in any of the major ball-playing nations. It may well also be the most elaborate museum structure dedicated exclusively to any single athlete in any major sport. More than twenty separate rooms and connecting hallways feature state-of-the-art interactive displays celebrating every important milestone of Oh’s career, from childhood days, through playing and managing careers, and on to the 2006 WBC championship triumphs. There are original balls and bats from every landmark home run and team championship, as well as family photos, personal scrapbooks, game-worn uniforms, and even a complete re-creation of the bedroom from his childhood home. The museum is in fact considerably larger and houses far more valuable memorabilia than even the central Japanese National Baseball Hall of Fame now housed in the country’s largest sports palace, the Tokyo Dome.

Oh’s home run records are today fodder for many heated debates among those wishing to make speculative comparisons with Bonds, Aaron or Ruth. The debates surrounding Oh’s actual achievements – especially as they might be speculatively compared with major league performance – also focus on the proposals voiced by many that Sadaharu Oh deserves enshrinement in the North American National Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown. Jim Albright in a well-reasoned and thorough online treatment has perhaps best capsulized the arguments in favor of (and opposed to) Oh’s recognition has baseball’s true home run champion. Albright actually breaks his argument into two quite distinct areas of debate and treats these topics in separate detailed online articles. Part I of Albright’s work tackles the issue of Oh’s actual Japanese record (with detailed statistical review not only of performances in Central League games, Japanese All-Star Games, and the post-season Japan Series, but also in 110 specific exhibition contests played against touring big leaguers); Albright then also offers some subjective analysis of the overall Oh record (including quoted observations by big leaguers and others who saw him play first-hand). In Part II (a separate article) Albright expands on the “subjective” argument by introducing the issue of “hypothetical projections” from the statistical record – the type of argument often advanced by those arguing for equating top Negro league stars with big leaguers from a similar era.16

Oh’s home run records are today fodder for many heated debates among those wishing to make speculative comparisons with Bonds, Aaron or Ruth. The debates surrounding Oh’s actual achievements – especially as they might be speculatively compared with major league performance – also focus on the proposals voiced by many that Sadaharu Oh deserves enshrinement in the North American National Baseball Hall of Fame at Cooperstown. Jim Albright in a well-reasoned and thorough online treatment has perhaps best capsulized the arguments in favor of (and opposed to) Oh’s recognition has baseball’s true home run champion. Albright actually breaks his argument into two quite distinct areas of debate and treats these topics in separate detailed online articles. Part I of Albright’s work tackles the issue of Oh’s actual Japanese record (with detailed statistical review not only of performances in Central League games, Japanese All-Star Games, and the post-season Japan Series, but also in 110 specific exhibition contests played against touring big leaguers); Albright then also offers some subjective analysis of the overall Oh record (including quoted observations by big leaguers and others who saw him play first-hand). In Part II (a separate article) Albright expands on the “subjective” argument by introducing the issue of “hypothetical projections” from the statistical record – the type of argument often advanced by those arguing for equating top Negro league stars with big leaguers from a similar era.16

The related Cooperstown argument is more complicated, even if one is of the opinion that Oh’s slugging can indeed withstand legitimate comparison with similar records established in the big leagues. Many North American Blackball stars have now been enshrined over the years, and few of the arguments in their favor are based on any easily defensible or thoroughly documented evidence that the Negro leagues and big leagues were in any way equivalent in talent level. There have to be other standards beyond mere box score numbers if one wants to broach the subject of comparing ballplayers across eras or across leagues of different stature.

And all this begs a much larger question, the parochial assumption of so many North American fans and commentators that professional baseball is an exclusively North American institution and therefore that Cooperstown is the only legitimate Valhalla to house the sport’s immortals. There is little evidence that Cooperstown enshrinement would mean anything to Oh (he never speaks of it) or to any of his multitudes of Japanese fans, or that such an honor would in any way amplify his substantial legend in the sport’s century-plus annals. One might as well be asking here if Joe DiMaggio’s New York Yankees legacy is in any way diminished by that fact that Joltin’ Joe never found his way into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame in Tokyo (although his one-time San Francisco Seals mentor Lefty O’Doul actually did).17 Such idle speculations comparing ballplayers from different leagues, epochs or countries are perhaps delightful fodder for Hot-Stove discussions; in the end they offer little true insight into any athlete’s true achievements.

No matter where one stands on competing interpretations of Oh’s actual statistical achievements, or on his true stature in the Japanese record books and in Japanese baseball lore, there is no room for argument concerning the fact that his remarkable career was the true stuff of baseball legend. No player outside of Babe Ruth himself has to date ever dominated for quite so long one of the game’s top professional leagues. None ever brought to the game a more revolutionary or unique style of hitting a baseball. Few if any of the game’s greatest on-field stars can also boast a more successful and celebrated managerial career. And if the diamond sport is ultimately a game of numbers – as so many of its commentators contend – no single batter in any of the world’s top circuits has left behind a more impressive and enduring numerical and statistical legacy.

Last revised: April 1, 2014

Acknowledgements

This author wishes to thank Sadaharu Oh for several brief but informative personal conversations at Fukuoka’s Yahoo Dome Stadium during the first round of the 2013 World Baseball Classic. But even more importantly this biographical essay owes a deep debt of gratitude to leading Japanese baseball scholar Rob Fitts whose careful reading and editing contributed to the final improved version.

Sources

Albright, Jim. “Sadaharu Oh and Cooperstown, Part I” online article (posted in 2002) at: BaseballGuru.com (http://baseballguru.com/jalbright/analysisjalbright12.html)

Albright, Jim. “Sadaharu Oh and Cooperstown, Part II” online article (posted in 2002) at: BaseballGuru.com (http://baseballguru.com/jalbright/analysisjalbright13.html)

Albright, Jim. “All-Time Foreign Born Team” (from the “Japanese Insider”) online article at: BaseballGuru.com (http://baseballguru.com/jaqlbright/analysisjalbright05.html)

Bjarkman, Peter C. Diamonds around the Globe: The Encyclopedia of International Baseball. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Publishing Group, 2005. See Chapter 3: Japan, Besuboru Becomes Yakyu in the Land of Wa (121-157).

Deford, Frank. “Move Over for Oh-san,” in: Sports Illustrated, Volume 47:7 (August 15, 1977), 58-67.

Ivor-Campbell, Frederick. “Sadaharu Oh’s Place in Baseball’s Pantheon” in: The National Pastime 12 (1992). Cleveland, Ohio: Society for American Baseball Research, 35-36.

Lefton, Brad. “Sadaharu Oh Still Feels and Thinks the Game,” The New York Times (May 4, 2008). Online article (http://www.nttimes.com/2008/05/04/sports/baseball/04oh.html?_r=0)

Oh, Sadaharu with David Falkner. A Zen Way of Baseball. New York: Times Books, 1984.

Whiting, Robert. The Chrysanthemum and the Bat – Baseball Samurai Style. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1977.

Whiting, Robert. You Gotta Have Wa* – When Two Cultures Collide on the Baseball Diamond. New York: Macmillan Publishing, 1989.

Wu, Debbie. “Baseball Great Has Roots in ROC,” The Taipei Times (November 16, 2003). Online article (http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/taiwan/archives/2003/11/16/2003076035)

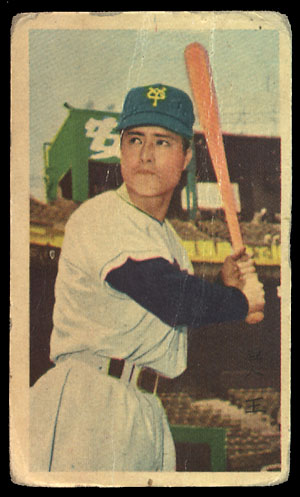

Photo Credits

Author’s Collection (Japanese Hall of Fame plaque photo by Peter C. Bjarkman)

Notes

1 The most thorough and sensible comparison between the quality of Japanese professional baseball and the game played in the big leagues (at least in relation to the case of Sadaharu Oh) may be found in the pair of online articles by Jim Albright arguing for Oh’s legitimate Cooperstown credentials.

2 Eric Neel (“Second look at A Zen Way of Baseball”) writing in his “Page 2 Column” on: ESPN Page 2 (http://espn.go.com/page2/s/neel/020814.html/)

3 If Oh was overshadowed by Nagashima in Tokyo popularity polls, he in turn far outdistanced his more adulated teammate in the record books. As Jim Albright stresses in the second article of his two-part series, during their 15 overlapping seasons Oh recorded 645 more games played, 1156 more at-bats, 697 more runs scored, 315 more hits, 424 more homers, and 648 more RBI. Nagashima twice paced the league in homers; Oh did so 15 times. Nagashima captured a single Triple Crown (1961), Oh claimed two (1973, 1974). Nagashima did hold a six-to-five advantage in Central League batting crowns, but Oh claimed a nine-to-five edge in league MVP trophies. The only clear advantage for Nagashima was in career batting average where Shigeo maintained a slim final lead (.305 to .301); but that final edge might well be explained by a shorter career span of five less seasons.

4 Whiting’s claims (The Chrysanthemum and the Bat, 100-101) seem to contain at least a small element of hyperbole, but unlike most North American writers he was at least close to the Japanese baseball scene at the time in question. Whiting further contends that “of all sports heroes in the world, only Brazil’s Pele can claim Nagashima’s stature,” and also that “Joe Namath and Muhammad Ali have their detractors but Nagashima has none.”

5 The best sources for discussion of the racism that defines Japanese baseball are found in the several excellent books by Robert Whiting, especially his earliest volume. I also elaborate more on this phenomenon in my SABR Biography Project essay on the life of Victor Starffin – having been born outside Japan, owning clear Caucasian features, and reaching his peak career during the World War II decade of extreme nationalism, Starffin was of course a far more obvious victim of Japanese exclusionism than was Sadaharu Oh. Another useful source on the “Gaijin” problem in Japanese baseball is Jim Albright’s online article devoted to selecting an all-time Japanese League foreign-born team (see references above).

6 Oh pays loving tribute to his parents and their sacrifices on his behalf in his autobiography, although never refers to them by their given names. His mother, Tomi Oh was born in the city of Toyama (in September 1901) and lived until August 17, 2010, when she passed away peacefully in Tokyo at the remarkable age of 108 years.

7 Oh explains the discrepancy in birth dates as follows. As the puniest of a pair of fraternal twins, he was not expected by doctors in attendance to survive more than a handful of days. Believing that he would not make it beyond the first week of life, his parents reportedly altered his birth certificate in order not to be burdened with the red tape of later filing a separate death certificate (given the expectation that he would already have deceased by the time his posted “official” birth date of May 20 arrived). Ironically it was the twin sister, Hiroko, who would succumb to a severe measles infection only fifteen months later.

8 See Oh’s A Zen Way of Baseball, 34. Oh attributes the successes of his uncle and brother in convincing Shifuku to allow his youngest son to pursue baseball dreams at Waseda mainly to their honest approach that eschewed any tricky strategies. The true irony here was that the father wanted both his sons to enter professions that could serve humanity and aid fellow citizens. In the end, as one of Japan’s most celebrated athletes, Sadahura would of course have a far greater impact on his nation and its baseball-crazy citizenry than any career in engineering would likely have provided.

9 The Chrysanthemum and the Bat, 2. Writing in 1977, Whiting reports that 60,000-plus would attend each game during a pair of annual three-game series between the two schools. Each school’s fans were spurred on by “karate-chopping cheerleaders and raven-hair pom-pom girls” and those games also drew a nationwide television audience similar to the one also fixated each spring on the Koshien high school tournament matches.

10 The more prestigious summer Koshien event involved a preliminary national qualifying tournament in which more than 1,700 teams competed, 124 from the city of Tokyo alone. Details are found in Oh’s A Zen Way of Baseball, Chapter 2.

11 See A Zen Way of Baseball, 55-57. Oh would later also remark that (perhaps as a result of this high school experience) he always rejected the option of seeking Japanese citizenship since it would prove little in light of the fact that everyone knew he was Chinese anyway.

12 Oh’s first two plate appearances (both strikeouts) came against Japan’s all-time strikeout king, Masaichi Kaneda of the Kokutetsu Swallows (a hall of famer, the league’s only career 400-game winner, and also the country’s career leader with 4,490 Ks). Ironically, one year earlier famed teammate Shigeo Nagashima also debuted ignominiously with the Giants by striking out four consecutive times against the same Masaichi Kaneda.

13 The period of intense sword training began immediately after the 1962 season (his first as league home run champion) and lasted for more than two years (encompassing the 1963 and 1964 calendar years). Oh explains his physical and spiritual training regimen as a key element in the traditional samurai warrior’s devotion to rigid self-discipline, a key element of Zen beliefs. In addition to the further guidance and inspiration provided by Arakawa during this period, the daily sword sessions were carried out in the Haga Dojo training center of Master Haga Sensei.

14 The middle daughter – Rie Oh (born in 1970) – would later become a talented Japanese sportscaster and a featured celebrity on Japan’s popular J-Wave radio network. Like their father, all three Oh children hold Taiwanese rather than Japanese citizenship, although none of them learned to speak any Chinese.

15In July of 2006 Oh underwent laparoscopic surgery to completely remove his stomach and all surrounding lymph nodes. Although suffering major weight loss and able to eat only slowly and sparsely, Oh returned to his position as manager of the Fukuoka SoftBank Hawks less than 20 months after the major surgery.

16 As Albright admits, many will dismiss as “pure fantasy” the mathematically complex projections which aim to assess how any non-big leaguer might have done in the majors by assessing parallel performances in another league (often tweaking those performances through questionable speculations, such as comparisons with actual posted numbers for a small handful of other contemporary players who performed in both leagues). Using his complex formulas Albright eventually adjusts Oh performance to show a potential 527 big league round trippers, nearly 5000 total bases, and respectable career batting (.279), slugging (.484) and on-base (.412) percentages. One small argument in favor of Albright’s approach is that in Oh’s case at least the projections are based on a wealth of accurate statistical data of the kind largely unavailable in the cases of just about all former Negro league stars.

17 Frank Deford ends his insightful 1977 Sports Illustrated article devoted to Oh’s chase after Aaron’s big league record (it was written with Oh sitting on 742 homers) by speculating on how glorious for American baseball it might be to one day see Aaron and Oh induced jointly into Cooperstown’s pantheon. (“But [Deford mocks], of course, the Special Committee will put in another octogenarian umpire from the Federal League instead.”) Deford’s admirable point here is to emphasize the parochial North American view of baseball as a strictly American possession. He argues that the most frequently raised question about Oh (whether he could have been a true star in the majors) is in the end both “diverting and condescending” since “it keeps us from properly considering the man in his own environment.” See Deford, 58 and 67.

Full Name

Sadaharu Oh

Born

May 10, 1940 at Tokyo, (Japan)

Stats

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.