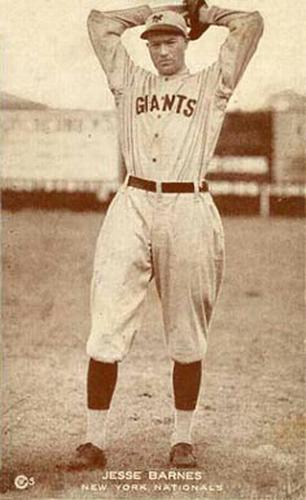

Jesse Barnes

When Jess Barnes was at the top of his game, the right-handed pitcher from Circleville, Kansas, held his own with the elite of his day. Named to Baseball Magazine’s All-American team following the 1919 season, Barnes shared the honor with such luminaries as Walter Johnson, Rogers Hornsby, Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, George Sisler, and Joe Jackson. His career accomplishments were not, in the end, weighty enough to lodge him forever in that exclusive company, but during his twelve years in the major leagues spanning the period 1915-1927, Barnes stocked his résumé with an impressive array of highlights and dramatic moments.

When Jess Barnes was at the top of his game, the right-handed pitcher from Circleville, Kansas, held his own with the elite of his day. Named to Baseball Magazine’s All-American team following the 1919 season, Barnes shared the honor with such luminaries as Walter Johnson, Rogers Hornsby, Ty Cobb, Babe Ruth, George Sisler, and Joe Jackson. His career accomplishments were not, in the end, weighty enough to lodge him forever in that exclusive company, but during his twelve years in the major leagues spanning the period 1915-1927, Barnes stocked his résumé with an impressive array of highlights and dramatic moments.

In 1919, he led the National League in wins, and was the winning pitcher in the fastest nine-inning game ever played in the major leagues. In 1921, he was acclaimed as a World Series hero. In 1922, he pitched a no-hitter. In 1924, he logged 267 2/3 innings without throwing a wild pitch or hitting a batter, still a National League record. Along the way, he played checkers with Mathewson, struck out Ruth, and dueled with Alexander.

Straddling the Deadball and Liveball eras, Barnes plied his trade on behalf of the Boston Braves (twice), New York Giants, and Brooklyn Robins, and compiled a major league record of 152-150 with an ERA of 3.22. Although he pitched fewer than half of his games for the mighty Giants, most of the sweet spots in Barnes’ career were clustered in New York. His record with the Giants was 82-43, which at .656 still ranks fourth in winning percentage among all Giants franchise pitchers with 100 or more decisions.1 The glory days were in New York, but even in Boston, where the Braves performed dismally during much of his tenure, Barnes left an imprint which has endured—his ERA of 3.07 with the Braves is still seventh best among modern era Braves franchise pitchers who worked 1,000 or more innings.2

At 6’0” and 170 pounds, Barnes was lean, lanky, and fit. According to Ernie Quigley, long-time National League umpire and fellow Kansan, Barnes pitched “like pitchers are supposed to pitch,”3 and had mastered what Quigley considered to be the three pitching essentials: fastball, curve, and control. Barnes regarded himself primarily as a fastball pitcher—“I could pitch fast balls all day”4—but the other pitches in his arsenal, the curve and the changeup, were featured in some of his most celebrated performances. His pitching arm would later develop something of a mind of its own, but during his prime, control was a Barnes hallmark.

The Road to the Majors

The start of Barnes’ story is a humble one, but even at the beginning, he was part of an adventure. Jesse Laurence Barnes5 was born on August 26, 1892, in Oklahoma Territory, the setting for a short-lived dream that failed to pan out for his parents, Luther and Sade (née Sarah Eva Bailey). Nearly a year earlier, the couple, still in their twenties, had left their home in northeast Kansas with their young son Guy and migrated to Oklahoma, drawn by the lure of free land which opened up in the Land Run of September 22, 1891. In competition with 20,000 others, Luther and Sade Barnes successfully laid claim to one of the 6,100 homesteads available for settlement, a 160-acre parcel located in what is now Cimarron Township, Lincoln County, Oklahoma.

Although his birthplace typically is given as Guthrie, or sometimes Perkins, it was on his family’s rural homestead that Jess Barnes drew his first breath. On the night Jess was born, Luther had committed to play fiddle at a dance held in a nearby country school. Since the school was visible from the Barnes homestead, Sade and Luther agreed on a lamp-in-the-window signal in the event Sade went into labor. Luther paid a youngster a nickel to be his lookout, and when the boy spotted the light, the music and dancing quickly came to an end. Luther rushed home to perform midwife duties at Jess’ birth, aided only by a medical reference book.

Homesteading was arduous under the best of circumstances, but in attempting it at the time they did, Luther and Sade steered into a heavy economic headwind spawned by the Depression of 1893. Sade, in particular, was known to have been unhappy in Oklahoma. In the fall of 1893, two years after arriving and a year after Jess’ birth, the couple disposed of their Sooner land and returned to northeast Kansas, where they had roots and family, and where community life was more established. They settled near Ontario, a small town on the Jackson/Nemaha County line and now long gone, in the same general vicinity where they had farmed during their first years of marriage.

For a while, Luther again tilled the land in Nemaha County, but he gradually moved towards other means of supporting the growing Barnes family. He became a vegetable gardener who marketed his produce locally, and rounded out his work life by hiring out as a house plasterer, farm laborer, handyman, railroad laborer, and at one point, as a government contractor to dig water wells on the nearby Potawatomi reservation.

By early 1902, the Barnes family had moved from the country into the nearby farm community of Circleville, a Jackson County town of 225 that bustled in a small-town way, thanks in large part to the rail lines that connected it to agricultural markets and larger urban centers. By 1908, the family composition was complete. Luther and Sade produced 10 children, three of whom died young. An unnamed child died in infancy, daughter Agnes died at the age of one in 1888, and son Guy, aged eight, died suddenly in 1897. Of the surviving children, Jess was the oldest, followed by Gladys (b 1895), Virgil (b 1897), Juanita (b 1899), Hattie May (b 1901), Charles (b 1905), and Clark (b 1908). Jess—whose childhood nickname was “Spot” because his face was blanketed with freckles—was nine when the family moved to Circleville. His education had started in the country schools close to Ontario and Bancroft, and continued in Circleville, where he remained on the pupil rolls until 1913. No records have been found to indicate that he graduated from high school, however.

With nine family members supported by a laborer’s wage, the Barneses’ lifestyle was no doubt austere, but the family embraced the cultural enrichments that were available to it. Luther was self-educated and political, an ardent Populist who greatly admired William Jennings Bryan. Sade was an amateur artist who had an appreciation of the classics; the poet Virgil may have been an inspiration in the naming of the couple’s second eldest son. Both parents were musical—Luther, as noted earlier, played the violin and Sade, the piano—and music was a popular form of family entertainment. Jess followed the musical lead of his parents and is known to have played at least the banjo and saxophone. He had a fine singing voice and, as an adult, joined with the other three brothers in singing barbershop harmony.

For the four Barnes sons, however, the defining feature of childhood was Luther’s love of sports, especially baseball. Luther had been an amateur pitcher in his own day, and he carefully created an “atmosphere of baseball” in rearing his boys.6 He instructed them in the basics of the game and introduced them to a training regimen when he added to their daily chores the task of pitching a baseball into a peach basket nailed to a shed. He also made sure that they had a place to hone their skills. The seven McKinley Avenue lots purchased by the family on the edge of town faced open country to the north and provided ample room not only for Luther’s gardening operation, but baseball practice as well.

Jess’ youth was filled with school, the raucous rhythms of a large family, baseball drills and games, and the laid-back freedoms found in small town life. He helped with the vegetable garden and, at the age of seventeen, reported “gardener” as his first occupation. As he advanced through his teenage years, however, the baseball lessons learned at the hands of the father took him further and further away from the gardening and practice lots on McKinley Avenue.

The first reports of Jess Barnes’ entry into the world of amateur ball occurred in the summer of 1909, when one news item in the Jackson County World placed him on the Circleville town team, and another placed him, at least for a short series, on a team in the neighboring community of Corning. Circleville did well that year—at the end of July their record was 21-7—but Barnes’ contributions to the team’s success are not known since the news accounts did not include lineups, line scores, or box scores. In the items found, he was mentioned by name in the account of only one Circleville game, a wild, extra-inning affair played against Goff as part of the Fourth of July festivities in Wetmore, Kansas. Playing before a crowd of 600 for a $50 winner-take-all purse, Circleville won the game, 5-4, in the eleventh inning. The Wetmore paper reported that Circleville had sent about 200 citizens in support of its team, which, if true, would have been pretty much the whole town.

The following year, Barnes competed in the only season of the Eastern Kansas League, which was designated as a Class D league, the lowest level in Organized Baseball at the time. The league was comprised of teams from six northeast Kansas towns. Barnes was “the kid” who played first base for the Holton team, where he did well enough to foster speculation about his prospects for advancing to the next level. When the Holton team folded in early August 1910 and its franchise was transferred to Blue Rapids, Barnes did not move with the team but instead signed a contract to play first base with the league’s Seneca team at a salary of $80 a month. Seneca was his first recorded contract with an officially sanctioned team in Organized Baseball.

In the 1911 season Barnes played for a town team in Nebraska. During this time, he also toured with a semipro team that barnstormed in Kansas and Nebraska. Somewhere in Nebraska, he crossed paths with catcher George Shestak, whose recommendation and contacts led Barnes to a tryout with the Keokuk Indians of the Class D Central Association. First base was his regular position, but Keokuk needed a pitcher, not a first baseman. Barnes decided to take a chance on his arm, a “pretty fair whip,” and presented himself to Keokuk as a “first class twirler.” 7 The pitching tryout went well enough to secure a contract for 1912, thereby setting his career on a fortuitous new course. During the 1912 season he compiled an 11-14 record for the Indians, a team that finished 49-76, a distant 29 games behind the league leader.

Although the Keokuk team fared poorly, Barnes’ performance there led to a promotion. In October 1912, Barnes was drafted by the Davenport Blue Sox of the Class B Three-I League, where he signed on to pitch in the 1913 season at a salary of $120/month. Davenport proved to be crucial in Barnes’ development as a pitcher, and he would later recall his time in the community with great fondness. The coaching and support he received in Davenport soon produced results. His record in 1913 was 20-10, and his winning percentage of .667 ranked sixth among the league’s pitchers.8 By the spring of 1914, some observers considered him the most promising pitcher in the Three-I League, and he earned his first shot at a major league job.

In May 1914, the Chicago Cubs purchased Barnes’ contract, subject to satisfactory completion of a 30-day trial. The tryout did not go well, and manager Hank O’Day sent him back to Davenport at the end of the trial period. Several years later, Barnes expressed his view that he had not been given a fair chance by the Cubs—he saw no action in a game situation, warming the bench instead, and was mainly asked to work batting practice when nobody much was looking.9 Different news articles offered different thoughts about the reason for his release: his arm went dead at a critical juncture; Davenport’s asking price was too high; he did not have enough physical heft to withstand the rigors of major league play; he just failed to impress. Whatever the reason, Barnes returned to Davenport, where he helped the Blue Sox win the franchise’s first league championship title in 1914 and where, in 1915, he became the league’s dominant pitcher. His midseason record of 18-6,10 with an ERA of 1.38,11 propelled him again to the big leagues, this time for good.

The Show in Boston

The call to the major leagues came from the Boston Braves on July 25, 1915, when the team paid Davenport $2,500 for Barnes’ contract. Barnes had been scouted by Mike Kahoe, who recommended him to Jim Gaffney, Braves owner, shortly after Kahoe himself had been hired by the club. Barnes debuted for the Braves on July 30, 1915, in Cincinnati, where he went two innings in relief but was not a factor in the team’s loss to the Reds. His first start, first win, and first complete game all occurred in Brooklyn on September 8, when he “burned the ball down the trail” and allowed the Robins but five hits and one run.

Barnes’ break-in with the Braves during the final two months of the 1915 season was auspicious—his record after 45 1/3 innings at the major league level was 3-0 with an ERA of 1.39. Yet, for all the promise in the beginning and despite the pitcher-friendly dimensions of Braves Field, Barnes’ 19-36 record over the next two seasons with the Braves was disappointing.

A shoulder injury early in the 1916 season precluded any carryover momentum from 1915. Although allusions to arm problems would surface occasionally throughout Barnes’ career, the period May-June 1916 is the only clear-cut instance found where an injury sidelined him for any significant period. He was placed on the inactive list for part of this time, and lengthy intervals were recorded between game appearances. He managed only one win during the first two months of the 1916 season.

A bigger problem, though, was the fact that the Braves had shed the “miracle” mantle of 1914, when the team had mounted a wonderfully improbable last-to-first pennant drive that culminated in a World Series sweep over Philadelphia. The Braves maintained respectability in both 1915 and 1916, but slipped markedly in 1917, when the team ended its season in sixth place, 25½ games behind the league-leading Giants.

Of Barnes’ 51 starts for the team in 1916-17, the Braves offense delivered only 2.96 runs per game in support, compared to the league average of 3.49, and the team lost 21 times while scoring two or fewer runs. In six of Barnes’ starts in 1917, his team was shut out altogether. His Boston teammates may not have given him the offensive support he would have liked, but they did give him an unusual nickname—Doorknob—because at 6 1/8, his hat size was the smallest in the major leagues. Variants of the moniker later evolved into “Nubby” and “Big Knub.”

Unquestionably, Barnes was the Braves’ workhorse on the mound in 1917. His team highs for the season included: 50 game appearances; 33 starts (including 27 complete games); 17 relief appearances (tied with Pat Ragan); 295 innings worked; and 21 losses. His loss total was the highest among National League pitchers, an unwanted distinction he shared with Eppa Rixey of Philadelphia. Carrying the heaviest load for a losing team did have an upside for Barnes, though, because he could showcase his talent on a regular basis, and by mid-1917, he was starting to get notice as a hard-luck pitcher with a great fastball and a future.

Despite the general implosion of his team and the grind of heading to the mound every three or four days for nearly five months, Barnes finished the final weeks of the 1917 season with authority, winning five of his last eight starts. On October 2, in his final game of the season, he entered the record book for a rather incidental feat when, in the third inning of a game with Brooklyn, he was walked twice by Jeff Pfeffer, and thus became the only pitcher ever to draw two walks from the opposing pitcher in the same inning.12

On two occasions in September 1917, Barnes in effect auditioned for the most powerful manager in baseball, John McGraw. On September 4, in New York, Barnes led the Braves to a 3-1 victory over the Giants. He “pitched some great ball in the pinches” and twice retired the Giants after they had loaded the bases. Ten days later in Boston, the Braves suffered a 5-0 loss to the Giants, but all five runs were made in a scoring flurry following a fielding error on a play that should been an inning-ending out—thus marring an otherwise solid pitching performance.

A Giant Upgrade, A Season Interrupted

Whether in the fall of 1917 or earlier, Barnes had caught McGraw’s attention. The biggest break of Barnes’ career occurred on January 8, 1918, when he became a member of the New York Giants. Barnes arrived in New York via a three-team trade involving the Giants, Braves and Cubs. Charley “Buck” Herzog, Giant second baseman and team captain, was traded to Boston in a straight-up exchange for Barnes and “Laughing” Larry Doyle, a second baseman and former Giant, who had been traded from the Cubs to the Braves solely to round out the deal. Herzog and McGraw had been at serious odds since Herzog refused to accompany the team on its final western road trip of the 1917 season. Herzog wanted to leave New York, and McGraw was willing to accommodate—but not without receiving fair value in return. Barnes was squarely in McGraw’s sights as he entered trade negotiations with Boston.

What had seemed a done deal in January began to unravel in March. Herzog failed to report to the Braves, holding out for a higher salary and a signing bonus. Former Harvard football coach Percy Haughton, now president of the Boston team, gave ground on a bonus but considered the balance of Herzog’s demands to be unreasonable and he stood ready to cancel the deal. The outcome remained in suspense until April, almost literally to the last hour, when Herzog finally signed his contract with the Braves.

Another uncertainty loomed even larger for Barnes in the early months of 1918. When the Giants traveled north to begin the season, the country had been at war with Germany for a year. Major league teams had already lost 62 roster players to military service, and more were bound to follow through enlistment and the draft—the only questions being how many more, who, when and for how long. Barnes had registered for the draft in May 1917, and was awaiting his fate at the hands of the Jackson County, Kansas draft board. His younger brother Virgil (whose nickname was “Zeke”), soon to be on the Giants’ horizon himself, had enlisted months earlier and was on his way to France.

Anxiety about the future may have stalked in the background during his New York debut on April 17, 1918, but it hardly mattered to the outcome. Barnes and his teammates required only 75 minutes to dispose of the Robins in a seven-hit, 2-0 shutout. In the process, he gave New Yorkers a taste of his characteristic “cool under fire,” a steely nerve that was noticed early and valued highly by his new manager. Barnes thrived with his new team, winning six of the nine starts he made during the first several weeks of the 1918 season, and recording but a single loss. He had an ERA of 1.81, and took full advantage of the solid defense and run support delivered by his teammates. Then the hammer fell in the form of a notice to report for military duty, and his season was finished.

Jess Barnes was inducted into the U.S. Army on May 29, 1918, in Holton, Kansas. He was assigned to Camp Funston, a temporary training cantonment adjacent to Fort Riley, Kansas—only about 55 miles from Circleville. For the next eight months, his home would be the Camp Funston/Fort Riley complex and his mission, to learn the trench warfare techniques needed for deployment to France. Barnes initially was assigned to the 164th Depot Brigade and later was transferred to Company C in the 20th Infantry, doing well enough to be promoted to corporal during his tour of duty.

Jess was never far from a baseball, though, even in the Army. The camp sponsored a baseball team which practiced daily after the military training drills were done. The team represented Camp Funston in contests with other camps and military units, and traveled as far as Kansas City, St. Louis, and Little Rock to play. Barnes was one of the team’s pitchers, as reported in Trench and Camp, the Camp Funston newspaper, but there is some indication that he may have been experiencing a “sore arm” in mid-summer 1918. Only one account of a game appearance was found, that being against a Kansas City team on September 1, 1918, a game which Camp Funston won handily by a score of 4-0.

Barnes did not see action abroad but in mid-September 1918, war of a different kind visited Camp Funston, disrupting life there as it did throughout much of the world. The influenza pandemic struck nearly a quarter of the personnel at Fort Riley/Camp Funston, hospitalizing over 15,000 before dissipating in early November. It is not known whether Barnes took ill, but a Circleville news item in late October 1918 indicated that “most” of the town’s men at Camp Funston had been hospitalized with influenza. The end of the epidemic at Funston, or at least the worst of it, roughly coincided in time with the signing of the Armistice, which in turn cleared the way for resumption of Barnes’ career. He was discharged from the Army on February 6, 1919, in plenty of time for spring training.

A Career Year and Consecutive 20-Win Seasons

Upon joining his teammates in Gainesville, Florida, Barnes began prepping for the 1919 season under the guidance of the new Giants pitching coach and a fellow checker player, Christy Mathewson. Some of the most dramatic single moments in Barnes’ career would come later, but 1919 would be his high-water mark in terms of sustained performance over the course of a full season. In the abbreviated 140-game major league schedule played in that first postwar year, Barnes crafted a 25-9 record, leading all National League pitchers in wins. For most of the season, he found himself on a roll—not only did he compile an enviable pitching record, including an ERA of 2.40 and four shutouts, he notched a career-best .267 batting average in 120 plate appearances.

With the Giants locked in an early race for the league lead, Barnes managed to squeeze in an important personal milestone in the summer of 1919. After pitching a complete-game win over the Cubs during the Giants’ first western trip of the season, Barnes left the team and boarded a train for Kansas. Late the next afternoon, June 17, 1919, in a small ceremony at a Presbyterian parsonage in Topeka, he married Rebecca Margaret Shafer, his hometown sweetheart and former classmate from Circleville. Immediately after the ceremony, the newlyweds left for St. Louis, where he rejoined the team in time for his next scheduled start, a 4-2 victory over the Cardinals.

Throughout June and July, the Giants and the Reds engaged in a gripping race for the National League lead. The Giants started to blink in early August, but a huge six-game showdown with the Reds loomed at the Polo Grounds in mid-month. Cincinnati swept the first of three doubleheaders, and the Giants swept the second. In the final and deciding set, Barnes was the starting Giant pitcher in the first game, which proved to be a “nerve-tingling demonstration of two fighting teams.”13

The game turned on a fielding error followed by one bad pitch in the fourth inning. The inning would have been over, save for an error committed by Giant shortstop Art Fletcher while attempting to tag a runner in a base-stealing play at second. After giving an intentional pass to bring Reds pitcher Hod Eller to the plate, Barnes dished up a treat that Eller sent out of the park, driving in three runs. The Giants went on to lose in a heartbreaker, 4-3. The loss broke up a win streak for Barnes, who had led his team to 10 consecutive wins in his 10 previous starts.14

A piece of Barnes lore survives from this game. Despite the fact that Eller was known for trick pitches, notably the shine ball, the Reds repeatedly asked the home plate umpire to examine the ball that Barnes was using. When the request came to scrutinize Barnes’ glove as well, he flung the glove at the batter in a fit of indignation. The glove ended up near the foul line, where it lay in silent protest as Barnes finished the game barehanded.

New York not only lost both halves of the final doubleheader with the Reds, falling 6½ games behind, the team also lost its main chance for regaining momentum. The Giants barely broke .500 the rest of the way, while the Reds never looked back.

Pennant hopes had evaporated, but Barnes still had a stake in the final weeks of the 1919 season as he vied for the league pitching title. Wins in September were the hardest of the year to come by for Barnes, and for a while it was an open question whether he would reach the 25-win benchmark. Two of Barnes’ September contests had significance beyond his own quest, however, and for very different reasons.

On September 10, 1919, Barnes entered a game in Chicago in relief of Fred Toney, who retired with a 3-1 lead after working two innings. Barnes completed the game, which the Giants won, 7-2. From news accounts at the time, it seemed a routine enough game, but a year later Toney testified to the Cook County Grand Jury investigating the Black Sox scandal that the game had been anything but that. As he later revealed publicly, Toney claimed that he had removed himself because he had been approached between innings by Heinie Zimmerman, the Giants’ third baseman, with a $200 offer to throw the game. Toney reported the incident to McGraw that evening, and the next day McGraw suspended Zimmerman for the rest of the season, without pay, ostensibly for missing curfew and repeated violation of team rules. When the real reason for the suspension became public, Zimmerman maintained his innocence, but he did not play in the major leagues again.

Later that month, on September 28, Barnes achieved his goal of 25 wins in a record-setting 6-1 contest between the Giants and the Phillies at the Polo Grounds. In that game, his last start of the season, Barnes became the winning pitcher of the fastest nine-inning game ever played in the major leagues, a game clocked at an astonishing 51 minutes.15 Plenty of action spiced the contest—18 hits (including a double by Barnes), 7 runs, 3 walks and an error—but it was action executed with unusual dispatch, even considering the shorter game times typical of the era. Accounts vary as to when the players shifted to a hustle gear—one suggests the sixth inning and another, the ninth—but there was no lapse in serious effort, except perhaps with the final at-bat, when Phillies shortstop Dave Bancroft made but a feeble attempt to put the ball in play. Barnes delivered only 64 pitches in the game, which the New York American reported at the time to be a major league record for the fewest pitches in a nine-inning game.

The last week of September 1919 was important to Barnes for another, more personal reason. His brother Zeke made his first appearance as a New York Giant, pitching two innings in relief in a road game against the Braves. Zeke had pitched for Sioux City since returning from Army service in France and had been given a tryout with the Giants, probably on Jess’ recommendation. Zeke was not yet ready for prime time—his first two major league innings were rocky, as he yielded six hits and four runs—but McGraw saw his potential, and later that fall the Giants purchased his contract from Sioux Falls for $3,000. Zeke played in the minor leagues for another two years, but his affiliation with the Giants was set, thus creating a “Barnes brothers” story line that would develop along its own track over the next several years.

Except for the pennant disappointment, 1919 had been a very good year for Barnes: the National League pitching title, the twenty-five wins, the fastest game, his marriage to Rebecca, and his brother’s new connection to the Giants. In the fall of 1919, however, clouds rolled in from an unexpected direction.

Jess Barnes and Giant center fielder Benny Kauff were good friends. Kauff was probably the flashiest member of the team, known for his flamboyance, his temperamental but fun-loving ways, and his finely-tailored wardrobe. Like Barnes, Kauff had wed in 1919, but sometime before their respective marriages the two had shared an apartment in New York. They socialized; their wives became friends. When Kauff decided to pursue a business venture, he asked Barnes to join him as a partner. Barnes agreed, but probably soon regretted it.

On September 4, 1919, Kauff and Barnes opened a tire store at 185 Columbus Avenue in New York City. The idea had first been pitched to Kauff by his chauffeur, Frank Hone, as a way of making extra money during the offseason. Hone was a baseball crank who relished his ties with Kauff; he often presented himself at Kauff’s brother, step-brother or half-brother, but Kauff denied any familial relationship. Since Kauff and Barnes would be away from New York much of the time, they agreed, at Kauff’s suggestion, that Hone would manage the store. Two other employees—James Shields and James “Buddy” Whalen—both salesmen, filled out the staff.

Their business plan mapped a short, straight road to disaster. During the early weeks of the store’s operation, Barnes and Kauff were absent for long stretches, first on road trips with the team and then on personal trips. While Kauff and Barnes were gone, the store’s inventory began to go missing. Sometime in November, they discovered that Hone had stolen up to a third of the store’s tires and was nowhere to be found. When they calculated the damage, the partners estimated that they had been hit with $4,000-$5,000 in losses from the stolen tires and other business expenses. Financial pressures ratcheted up quickly as the tire companies grew increasingly insistent in their demands for payment on the tires they had supplied the store. The Giants came partially to the rescue by giving the two players a loan, of an unknown amount, to help them work their way out of trouble. But trouble was not finished with them yet.

In mid-October, Barnes had bought a Cadillac, the first car he ever purchased, from Jimmy Shields, one of the salesmen at the store. Two months later, strapped for cash, Barnes sold the car to a dealer named William Reddington, using Kauff as his agent. Shortly thereafter, it was discovered that the Cadillac had been stolen, putting Barnes in the position of having to reimburse Reddington $1,100. Worse, both of the store’s salesmen—who had managed to sell all of seven tires between them—turned out to be car thieves. Not surprisingly, the store closed its doors for good in early January 1920.

After Shields and Whalen were arrested in February 1920, they helped police clear twelve car theft cases, and they alleged that Benny Kauff had participated directly in the theft and sale of one of the vehicles. Though he steadfastly proclaimed his innocence, saying that he had been duped and victimized by Shields and Whalen, Kauff was arrested, indicted, and placed under a legal shadow that would linger for more than a year, and ultimately prove a fatal blow to his career.

Offseason woes had set a new tone that continued into the 1920 season. The Giants broke slowly from the gate, with a 3-9 record, and languished near the bottom of the league standings into early July. The bats were cold and the pitching shaky—including Barnes, whose start on the season was 7-11.

The Polo Grounds harbored a raft of unsettling developments during the first half of 1920. Hal Chase and Heinie Zimmerman, the team’s infield anchors in 1919, were both gone in 1920 because of alleged game-fixing activities (although the reason for their absence would not become public until that fall). Frankie Frisch, the promising new infielder who had taken Zimmerman’s spot at third base, had an emergency appendectomy in April and was lost to the team until mid-June. Christy Mathewson, the beloved Giant legend and team coach, was in ill health and had to leave the team in early July, thus marking the start of his long battle with tuberculosis, thought to have been caused when he was gassed accidentally during a training exercise in World War I. Shufflin’ Phil Douglas, chronically high maintenance because of his alcohol binges, was suspended briefly in midseason for his “failure to keep in playing condition.” Benny Kauff, distracted by his legal problems, was having a sub par season, especially in the field, which finally prompted McGraw to send him to Toronto in early July so he could “pull himself together.”

Finally, the team began to stir and started a sustained run in July that placed them in the thick of the pennant race with the Brooklyn Robins and the Cincinnati Reds by late August. Barnes’ return to form was one of several welcome factors in the team’s turnaround. His season pivoted on July 9, 1920, when he faced off in Chicago against Grover Alexander in a classic duel. The game went thirteen innings, with neither pitcher allowing more than two hits in a frame. Both pitchers went the distance. In the bottom of the thirteenth, with two outs, Barnes finally gave up a single that scored the winning run for the Cubs. Although he lost the game, 3-2, it was a superb performance and signaled that he once again was in command of his pitching arm. From that point on, Barnes’ record was 13-4, allowing him to finish the year with a record of 20-15—his second and last 20-win season.

The Giants’ advance took them to one game off the league lead, but their momentum fell short of being enough. Despite having three pitchers with 20 or more wins—Art Nehf, Fred Toney, and Barnes—the team finished in second place, seven games behind the Robins, their interborough rival.

During the postseason, Barnes joined a squad of players led by McGraw to compete in Cuba’s “American season,” which in 1920 featured a month-long series of games beginning in mid-October between two Cuban teams, the Almendares Blues and the Habana Reds, and the American team composed primarily of Giants players. For the Americans—whose team was supplemented in late October by its headliner, Babe Ruth—the trip was an opportunity to boost their earnings for the year, to engage against high-caliber competition, and not so incidentally, to relax in a resort setting without the strictures of Prohibition.

One source gives Barnes a 1-2 record in Cuba with one tie,16 although another reports that he was winless.17 All accounts agree that he experienced a tough 1-0 loss to the Habana Reds when, though hurling a one-hit game, he loaded the bases with a walk, then forced in the winning run with another. An arm strain suffered in one of the early games apparently kept him out of action during the latter part of the series.

Signs of Wear But A Hero in October

By 1921 Barnes was beginning to be viewed as something of an “in-and-outer” and a “fading veteran.” Measured by number of starts and innings pitched, Barnes would still be one of the top three Giant pitchers in 1921, but he would no longer lead the rotation or receive the first or second nod to start in crucial games. When all was right with his arm, Barnes could be dominant and impressively so, but consistency had started to elude him. For the first time, his ERA would top the 3.00 mark in 1921. As Cullen Cain of the Philadelphia Public Ledger would later observe: “He has an uncertain arm. It goes bad on him and is coy.…and hard to please.” 18 Barnes himself, much later in life, told an interviewer that he had experienced arm trouble in 1921.19 There was evidence of struggle—he started the season with a 4-5 record—but this was an era when pitchers were expected to pitch through their problems, and Barnes had no extended absences during the season.

McGraw could be hard on his pitchers. Southpaw Art Nehf, a teammate of Barnes, observed that McGraw viewed pitchers as “cogs in a machine” and was not averse to “burn[ing] up a pitcher in two or three years” if the good of the team required it.20 In one interview, Jess stated that, “Speed pitching is natural pitching….It is the curves that get your arm.”21 The extent to which the curves got to Barnes’ arm is not known, but the mound mileage was beginning to add up. Entering 1921, he had pitched an average of 294 innings during each of his first two full seasons with the Giants, and his cumulative major league total now surpassed 1,100 innings. The manager had a strong affinity for the curveball and molded his pitching corps accordingly, expecting them to throw an “uncommon number of curves.” Jess Barnes, his brother Zeke, and Nehf all viewed heavy reliance on the curve as punishing to the arm.

There were off-the-field distractions during this time as well. The Kauff auto theft case finally went to trial in May 1921. For its day, it was star-studded. The witness list included not only Kauff and Barnes, but John McGraw, George Burns (Giant outfielder), John Tener (former National League president and former governor of Pennsylvania), Frank Graham and Samuel Crane, both New York sports journalists. The attorneys in the case were also on their way to prominence. Emil Fuchs, Kauff’s attorney, would later own the Boston Braves. Ferdinand Pecora, the assistant district attorney who prosecuted the case, would later receive prestigious appointments as the lead congressional investigator into the causes of the stock market crash of October 1929, as an initial member of the Securities and Exchange Commission, and as a judge in the New York state judicial system.

Barnes appeared as a defense witness on May 12, the fourth day of the trial, and was questioned extensively about his relationship with Kauff, their business partnership, the operation of the tire store, and his own actions relating to the purchase of two vehicles subsequently found to be stolen. There was plenty of heat in the witness box that morning, but McGraw saw no need to scratch him from his scheduled 3:30 start that afternoon in a game against the Cardinals. If Barnes was rattled by his encounter with the justice system, it was not evident early. His control waned, but not until the fifth inning, when he was relieved; the Giants prevailed nonetheless. The next day, Kauff was acquitted by a jury that required less than an hour to render its verdict, but the two friends would never again compete as teammates. Commissioner Landis, who had earlier suspended Kauff from play pending resolution of the court case, refused to reinstate him.

Hints emerged from the trial that Barnes may not have recovered financially from the tire store fiasco. In his testimony he stated that he and Kauff still owed the Giants for the loan they received when the tire store failed. Another worrisome development arose in early May. For the first time as a Giant, Barnes saw his name mentioned in a possible trade, as speculation paired him with infielder Goldie Rapp in a proposed transaction with the Reds for Heinie Groh. The trade did not materialize—although the Giants would later acquire Groh—but the mere mention of it suggested that Barnes’ standing with the team was not as secure as it had once been.

The distractions were not all unhappy ones, however. Worries about the trial, finances, or the possibility of being traded were more than offset by the eager anticipation of a new family member. Gloria Jean, Jess and Rebecca’s only child, was born in New York on July 4, 1921, just in time for an exciting pennant drive, a marvelous postseason, and the brightest, kindest spotlight of Barnes’ career.

Over a five-day period in October 1921, at the best possible time, Barnes would find his finest form and display it on a national stage not once, but twice, in exceptional outings against the New York Yankees. The buildup to Barnes’ dramatic postseason started in August. Although the Giants kept themselves within striking distance throughout the summer, the Pittsburgh Pirates held the league lead for most of the season’s first four months, seemingly in command and set to go the distance. In mid-August the Giants made a move, but in the wrong direction, slipping to 7½ games behind the Pirates. This was the Giant vantage point on the eve of a five-game showdown series with the Pirates—not a preferred spot, but still a perfect setup for making a statement. In the space of four days, the Giants swept the Pirates, knocked them on their heels, and reduced Pittsburgh’s lead to 2½ games. Some two weeks later, on September 11, the Giants took an undisputed lead they would not relinquish.

As in 1920, Barnes’ performance was much improved in the second half of the 1921 season, with a July-September record of 11-4. McGraw did not use him in the Pittsburgh series, but he won four of his final six starts, including two that contributed to the team’s 10-game win streak in mid-September. With the help of the Pirates, who capitulated twice in a doubleheader with the Cardinals, the Giants clinched the pennant on September 29—an off-day for them after having capped a 23-7 run.

The 1921 championship would be decided in one city, in one stadium. New York had its first dream series, the Giants and the Yankees, set to unfold in a best-of-nine format at the Polo Grounds, traditional home of the Giants and leased home of the Yankees. Not only would the World Series settle the year’s major league title, it was an opening volley in the battle for New York baseball supremacy, pitting the established order ruled by John McGraw against the new, upstart challengers led by the sport’s first megastar, Babe Ruth.

The Series opened badly for the Giants; their bats were silent in the first two games, and the team was shut out twice by a score of 3-0. Barnes dipped his toe in the water in Game One, when he pitched an uneventful inning in relief of Phil Douglas, yielding two hits but no runs. He was not a factor in the decision.

Game Three, played on October 7, was pivotal for the Giants but initially looked to be cut from the same cloth as the first two games. Right-hander Fred Toney, who had won 18 games in 1921, lost all control in the top of the third, failing to retire any of the five batters he faced. His last pitch of the day came with the bases loaded and yielded a two-RBI single by Babe Ruth. When McGraw sent Barnes in to relieve Toney, the Yankees led 3-0 with no outs. On the first play following Barnes’ entry into the game, Giant catcher Frank Snyder threw out Babe Ruth on an attempted steal of second base, significant because Ruth aggravated an elbow injury he had suffered in Game Two. The cut on the injured elbow became infected, and would later cause Ruth to miss the last three games (except for one at-bat as a pinch hitter) of the Series.

One of the runners Barnes inherited scored on a ground ball, but he escaped the third inning otherwise unscathed. He finished the game with seven strikeouts, one of whom was Ruth, allowing only four scattered hits and one earned run. Barnes, who was a left-handed batter, also ignited the first of two Giant scoring sprees. His leadoff single in the bottom of the third positioned him to score the first Giant run of the game and the Series; by the end of the inning, the score was tied. The Giants had an eight-run breakthrough inning in the seventh, and went on to win Game Three by a comfortable 13-5 margin.

The teams split the next two games, so the Series stood 3-2 in favor of the Yankees going into Game Six, played on October 11. Once again Toney got the start, but this time he did not survive even the first inning. The score was 3-0, advantage Yankees, when Barnes took the mound with two outs in the bottom of the first. The Giants quickly countered with three runs in the second. Barnes wobbled when he resumed work in the Yankee half of the frame, giving up a two-run home run to Chick Fewster, Babe Ruth’s replacement. From that point on, Barnes’ pitching baffled and confounded the Yankee offense.

Barnes reeled off 10 strikeouts in Game Six, setting a Series record for a relief pitcher which held until 1966, when it was broken by Moe Drabowsky.22 Barnes completed a “cycle of strikeouts” by fanning every Yankee player in the lineup (and second baseman Aaron Ward twice). Seven of the 10 victims accepted their fate with a called third strike. Although interspersed with walks, seven consecutive Yankee outs were recorded via the strikeout, including the entire side in the bottom of the fourth.

His world-class performance was not wasted. The Giants gained the lead when they mounted a four-run rally—including a hit and a run scored by Barnes—in the top of the fourth inning, and they eventually won the game, 8-5. At the end of Game Six, the Series was tied three-all. For Barnes, the Series was over, but he had helped to turn the tide. The Giants prevailed in Games Seven and Eight, capturing the championship by a margin of five games to three.

In the 16 1/3 World Series innings that he worked in 1921, Barnes faced 63 batters, struck out 18, walked 6, allowed 10 hits, and had an ERA of 1.65. He also went 4-for-9 at the plate, for an average of .444, and scored three runs. His was not the only impressive pitching performance in the Series—Yankee Waite Hoyt pitched 27 innings with an ERA of 0.00—but Barnes was a difference-maker. Twice he entered the fray in a time of peril, then steered his team away from the cliff’s edge by holding a potent offense at bay. Barnes, the fastball pitcher, brought the Yankees to heel largely with his curveball. In an article proclaiming Barnes as “The Hero of the 1921 World’s Series,” Baseball Magazine described his curves as having “a break as sharp as a razor…with wonderful control,” and estimated that up to 90 percent of the pitches he threw were curves. Johnny Evers, the former Cub second baseman and manager, said in a post-Series interview that Barnes had “curve[d] the Yankees to death,” and pointed to Barnes’ performance as a “vivid example of … curve-ball pitching at its best.”23 The Yankee batters found themselves “swinging shamefully at balls which they could not reach.”24

It was a time to savor, but the Series and the last few weeks of the pennant race had been pressure-packed and stressful. When it was over, Barnes was ready for the tonic of the countryside and eager for the pleasures of a favored pastime, hunting. Returning to Kansas as a celebrity, Barnes gave credit to his father, who had traveled to New York to see his son pitch, and plainly stated his immediate plans, “I need a dog and gun, a river bank with trees, sunshine in the country and a few squirrels, chickens and rabbits.”25

A Holdout, A No-Hitter, and A Series Stalemate

If 1921 ended on a sweet high note, its resonance dissipated early in 1922. On February 20 the Giants management confirmed that both Barnes and Phil Douglas—the pitchers who had accounted for four of the team’s five World Series wins in 1921—were being placed on the auction block, open to acquisition by whichever club offered the best deal. The team was not forthcoming about the details, but there was ample room for speculation about the reasons prompting the action. Douglas was well-known to be a handful; his alcoholism required that he be monitored almost constantly. Barnes was viewed as being past his prime. Probably more significant was the fact both players were contract holdouts who were trying to leverage their World Series achievements into higher salaries. It is possible that the Giants’ attempt to market Barnes and Douglas was not really that at all, but a pressure tactic meant to bring them into line in the renewal of their contracts. Although the Giants initially claimed to have received offers for both players, no bona fide bid was found to have been reported in the media. One National League manager, Irving Wilhelm of the Phillies, flatly stated that the Giants were just peddling “propaganda,” that his team could use Barnes and/or Douglas, but “there’s no way of prying them loose.”26 An additional clue might have been given in early January, when a Washington Post article reported that National League “magnates” had tacitly agreed not to deal with players who held out for large salary increases.

For two weeks the status of Barnes and Douglas remained uncertain. Despite the limbo he found himself in, Barnes reported for spring training in San Antonio. During an interview en route,27 he implied that, in his mind, there was a connection between the Giants’ action and the fact that he had not yet signed his contract. He also indicated that his differences with the team “were not serious,” would be resolved fairly easily, and had not warranted placing him on the market. Eventually, both he and Douglas came to terms with the team and signed contracts to play again with the Giants in the 1922 season. In Barnes’ case, the standoff, if it could be called that, appeared to have paid off. The dollar amounts are not known, but The Sporting News reported that Barnes beamed upon exiting his final contract session with McGraw, and exclaimed happy disbelief that McGraw had given him so much.

The spring of 1922 brought another important development for Barnes. Brother Zeke had trained with the Giants each spring since 1920, and had been called up to the major league team following completion of the Milwaukee Brewers’ season in September 1921. This time, Zeke would stay with the Giants when the team broke camp to begin the 1922 campaign. Luther Barnes, former amateur pitcher who had taught his boys every baseball thing he knew, had two sons on the roster of the New York Giants, the best team in the land.

Jess Barnes’ season stats in 1922 continued to trend downward; he would end the year 13-8, with 212 2/3 innings pitched and an ERA of 3.51. However, he still had a date or two with the extraordinary moment. One of these occurred on May 7, 1922, when he pitched his finest major league game, a 6-0 no-hitter against the Philadelphia Phillies, before a spellbound crowd of 32,000 at the Polo Grounds. Barnes chased perfection into the fifth inning, but then walked Cy Williams, the Phillies’ center fielder. Because Williams was later eliminated in a double play, Barnes faced only the minimum number of 27 batters in the game. Unlike his World Series gems, on this day he relied mainly on his fastball, which he threw with “faultless control.” Only three of his pitches were hit to the outfield.

The game had some edgy moments, though. The closest call came in the sixth inning, when Phillies catcher Butch Henline hit a slow-moving ground ball to Dave Bancroft, the Giants’ shortstop. Bancroft’s throw to first on the play beat the runner, but only “by an eyelash.” The crucial ruling at first was made by umpire Hank O’Day, the former Cubs manager who had shut the major league door on Barnes during his 1914 tryout with Chicago. Also in the sixth inning, Barnes lost his composure, not while pitching but during his turn at bat. Phillies relief pitcher George Smith had thrown several brushback pitches since entering the game, provoking protest from Giants players. Barnes must have been the target of one of these pitches—after grounding out, he argued with Smith and started after him, only to be restrained by the home plate umpire and Cozy Dolan, a Giant coach. In the seventh inning, a Philadelphia coach asked to see the ball Barnes was using. After inspecting it, he reportedly pointed out several marks or cuts to the home plate umpire, who threw the ball out and replaced it. Down to the final outs, Art Fletcher, Phillies manager and former Giant, tried to put his team back into the game in the top of the ninth by using three of his best hitters from the bench. The maneuver failed. In turn, his pinch hitters flied out to center, grounded out to second, and grounded out to short.

The Giants were on their way to winning another pennant in 1922, but the strength of the pitching staff was a concern for McGraw. In an effort to upgrade his pitching corps for the stretch drive, McGraw made a trade with the Boston Braves in late July, acquiring right-hander Hugh McQuillan for Larry Benton, Fred Toney, Harry Houlihan, and $100,000 in cash. McQuillan and Barnes soon became friends and running buddies. Away from the intense, competitive atmosphere of the ballpark, Barnes had a reserved, soft-spoken, and good-natured demeanor. But, he also had a rowdy side that was drawn to after-hours action—an interest shared by McQuillan. Characterized by one writer as “a couple of partying pitchers,”28 McGraw dubbed the pair Gallagher and Shean after a vaudeville duo that became popular with the Ziegfeld Follies in the summer of 1922. Although no stranger to night life himself, McGraw would sometimes mock and deride them as they hurried from the clubhouse, eager to start on the evening’s pursuit of a good time.

Jess and Zeke Barnes both had multi-year affiliations with the Giants, but 1922 was the only year when they both were on the team’s roster for the entire season. The brothers appeared in the same game on nine occasions during 1922, with Jess being the starter in six of the games. Of the nine joint appearances, four resulted in no decision for either brother, four resulted in a loss for Jess, and one resulted in a win for Jess and, in retrospect, a save for Zeke. The most interesting of their joint outings occurred on September 24, when both brothers appeared in relief of Rosy Ryan in a game against the Cardinals. Each brother delivered a home run pitch to Rogers Hornsby—his 41st and 42nd of the season—making Hornsby the first batter to homer off two brothers in the same game.29 Much later in life, Jess Barnes made it clear that he viewed Hornsby as something of a nemesis, calling him “the greatest hitter of them all.” 30

In the early fall of 1922, although it was not publicly revealed until December, Barnes’ name entered into the mix in a possible Giants-Reds deal. The Reds had asked waivers on pitcher Dolf Luque in September, just months before he began his best season: in 1923, he would lead the league with 27 wins. Garry Herrmann, president of the Reds, also wrote to McGraw around this time, inviting him to make an offer for Luque. McGraw was not interested in acquiring Luque at the waiver price, but he offered Barnes instead. McGraw received no direct response, but in December Herrmann told the Cincinnati newspapers that he had refused the Barnes-for-Luque trade proposal, implying (wrongly, in McGraw’s view) that the Giants had first broached the subject of acquiring Luque.

The 1922 postseason was a reprise of 1921 in that the Giants, who clinched the pennant on September 25, would once again face the Yankees at the Polo Grounds, this time in a best-of-seven format. Although the Giants had a league-leading team ERA of 3.45, the consensus view going into the World Series was that Giants pitching was a worry, especially considering the importance of pitching strength in a short series. The team had lost one of its starters to scandal in August, when it was learned that Phil Douglas had written to Leslie Mann, an outfielder for the contending Cardinals, with an offer to desert the Giants in exchange for compensation. At the time he was expelled from the team, Douglas had an 11-4 record and an ERA of 2.63. There were question marks of one sort or another surrounding most of the remaining Giant pitchers. One New York Times article later stated that when the Giant hurlers took to the mound, most of them were thought to bring little more than a “glove and a prayer.” The three best—Art Nehf, Rosy Ryan, and Barnes—had season wins of 19, 17, and 13, respectively. In contrast, the top three of the Yankee rotation—Joe Bush, Bob Shawkey, and Waite Hoyt—had 26, 20, and 19 wins. On the eve of the Series, the question was whether the Giants’ high-octane offense, with its team batting average of .305, and its infield with three future Hall of Famers (George Kelly, Frank Frisch and Dave Bancroft), would be sufficient to compensate for the shortcomings of its rotation.

Compared to 1921, Barnes in 1922 had two fewer wins, his ERA had climbed from 3.10 to 3.51, and the finish to his season was not as strong. He had been relegated to the bullpen in October 1921, yet a year later McGraw handed him the ball to start Game Two. His starting assignment was a reflection of the general state of affairs in the Giant rotation, but it probably also had something to do with the class he had demonstrated the year before. He had gained the reputation of being “one of the best ‘money players’ in the game,”31 able to elevate his level of play when the stakes required it.

Game Two was played on October 5, a sun-filled day more summer than fall and perfect for baseball. Dressed in road gray, Barnes took the hill in the bottom of the first inning and embarked on a “splendid battle” with Bob Shawkey that would lead to one of the strangest finishes in World Series history. Barnes entered the game under circumstances much different from those he had encountered in the 1921 Series. This time, the Giants had a one-game advantage, having won behind Rosy Ryan the day before, and his teammates had handed him a three-run lead—instead of a three-run deficit—before he even touched the ball. Three runs were all that he would get, though, and the Yankees chipped away. An unearned Yankee run scored in the first. Aaron Ward, the weak-hitting second baseman, homered in the fourth with two outs. Babe Ruth scored in the eighth.

McGraw orchestrated the pitch selection, and Barnes executed the manager’s strategy beautifully. Because the Yankees were known for their fastball hitting, the idea was to strictly ration their pitch of choice, even though Barnes, when he used it, threw his fastball that day like “a man snapping a whip.” As in 1921, McGraw’s strategy in Game Two emphasized use of the curve, but he also directed Barnes to introduce an effective new weapon—the “slow ball,” probably referring to what is now known as the palmball. In describing Barnes’ slow ball, a writer for the New York Times reported that the pitch “floated up in a lazy droop” and moved so slowly that “the seams stood out before the eye.”

One of the prime recipients of the slow ball/curveball treatment in Game Two was Babe Ruth; Barnes did not offer Ruth a single heater in five at-bats. He fed Ruth so many slow balls that the crowd, unaccustomed to the pitch, twice jeered Barnes because they mistakenly believed that he was avoiding a head-on confrontation with Ruth. The crowd may have grown impatient at times, but seasoned eyes were more appreciative. Barnes’ masterful delivery—the wafting slow balls, the curves that “flecked the plate like a lash,” the fastballs that sometimes bordered on unhittable—was described in one article as “a delectable treat in pitching.” Even McGraw was generous in his praise: “Jess Barnes was working wonderfully. He had a greater variety of curves and slow balls than I had knowledge of. He’s a top notch pitcher. He’s got the fighting spirit in him, too.”32

The Giants were clinging to a thin one-run lead in the eighth inning when Ruth stepped down the timing of his swing and, in his only hit off Barnes, doubled a slow one off the end of his bat to left field. He advanced to third on a long fly to center, then scored when left fielder Bob Meusel doubled. Ruth’s run knotted the game forever at 3-3.

They played through 10 innings. As the Yankees trotted out to take the field for the top of the eleventh, George Hildebrand, the chief umpire, caught the entire stadium off guard with the stunning announcement that the game was being called because of darkness. As the news registered, thousands in the stands roared their disapproval since it was 4:40 p.m., with an estimated 30-45 minutes of daylight remaining. Hundreds converged around Commissioner Landis as he left the stadium, venting their anger at the game’s abrupt, inconclusive end.

Hildebrand and one of the other senior umpires, Bill Klem, had started discussing visibility conditions as early as the eighth inning. By the ninth, they agreed that the game should be called after the tenth if the score remained tied. A haze had settled in that sometimes camouflaged the ball, both at the plate and in the field, prompting complaints from several Yankee players. The pace of the game had been slow, and the officials were concerned that playing conditions would deteriorate unacceptably if another inning were attempted.

So, for the third and last time, a World Series game ended in a tie.33 Neither the commissioner nor the clubs had a part in the decision to suspend the game, but they were left with a huge public relations problem. Fans were disgruntled about having been cheated out of a chance for a proper finish, and some suspected that, in extending the Series, Organized Baseball had seized an opportunity to pry more money from their collective pocket. In an attempt to defuse the issue, Commissioner Landis, after meeting with the owners of the two teams, released a statement later that evening saying that the entire proceeds from the game, about $120,000, would be donated to New York charities.

The action may have mollified the public, but it stoked player discontent that had already been building on other fronts. Efforts had been underway since the spring of 1922 to organize a players union, and the decision to donate Game Two receipts gave at least a temporary boost to the cause. Hastily convened “fraternity sessions” among Series players were held to discuss the matter, and there was some talk of staging a walkout before Game Three. Although the players decided not to mount a public protest, the matter represented one more point of contention between baseball’s management and labor.

Another Series intrigue played out beyond public view, one in which Barnes is known to have played a role. Giants bench jockeys, including Barnes, had taunted Ruth aggressively through the first three games, riding him, as Ruth said, “with spurs.”34 Ruth thought some of the epithets being used went beyond the bounds of good sportsmanship, so he and Bob Meusel went to the Giants clubhouse after Game Three, looking to have a conversation with Johnny Rawlings, the utility infielder Ruth thought to be the worst offender. Before the pair could find Rawlings, they were greeted by other Giants players who gave them a testy welcome. Barnes gravitated to the middle of the action and challenged Ruth, telling Ruth he had a “hell of a nerve” coming over to bring Rawlings to account, considering some of the things Ruth had called Barnes when he pitched the previous day. Ruth denied calling Barnes any names, which Barnes angrily retorted was a lie. As their tempers flared, the two shed their coats and were preparing to square off when cooler heads intervened. Accounts vary as to who de-escalated the situation—McGraw, other players, Hugh Jennings—but shortly thereafter, the Yankees were asked to leave, which they did to the sound of Giants laughter.

For all the tension, the controversy surrounding Game Two, and the early worry about pitching, the Giants won the 1922 World Series in four straight decisions (excluding the tie). Rosy Ryan, Jack Scott, Hugh McQuillan, and Art Nehf each earned a win. The Giants’ team ERA for the five games was 1.76; the Yankees had hit a paltry .203 against them. In his 10 innings, Barnes matched the team standard with a 1.80 ERA, allowing eight hits, two earned runs, and one home run.

The Series over, Barnes returned to Kansas with plans to spend the fall hunting with Zeke. However, competing at the highest level of his sport had not dulled Barnes’ appetite for the smaller-scale rivalries found in town team ball. On October 29, he was the starting pitcher for Holton in a game against Valley Falls, played on neutral ground in Topeka. He pitched nine innings before being relieved by Zeke in the tenth. In a bit of déjà vu, the 2-2 game went 11 innings before being called because of darkness.

Barnes had an abbreviated offseason. In early February 1923 he, along with Giants rookie Clint Blume, went to Ithaca, New York, to work out with and provide instruction to the pitchers on Cornell University’s baseball squad. The pair spent two weeks coaching a dozen student-athletes, an assignment that also gave them a head start in their own conditioning for the spring.

The imminent arrival of spring training portended the possibility a contentious go-round between players and management over contracts and salaries. During the offseason, activity surrounding the new National Baseball Players’ Association had picked up. By December, it was estimated that 132 National League and 93 American League players had joined, representing almost one-third of the players on major league rosters. By mid-February, a players strike seemed at least possible.

It was reported by the New York Times that “practically every member” of the Giants had joined the organization, with Dave Bancroft, team captain, being among the most active. McGraw generally viewed the union’s members as ingrates and was angered by the fact that the organization had been embraced by so many of his own team’s members, who were among the highest paid in baseball. The Giants clearly viewed the players’ attempt to organize as a development in need of quashing. One of the team’s most visible actions in response was to ban from spring training camp any player who had not yet signed his contract.

The Giants’ pitchers and catchers were the first to face a confrontation since they had an early reporting date of February 22 at Marlin, Texas, for advance workouts before the start of the full camp on March 1 in San Antonio. As of February 19, only one frontline pitcher, Hugh McQuillan, had signed. Holdouts at that point included six members of the pitching staff (Jess and Zeke Barnes, Art Nehf, Jack Scott, Bill Ryan, and Jack Bentley, an offseason acquisition); and four position players (Frank Snyder and Earl Smith, catchers; Dave Bancroft, shortstop; and, Johnny Rawlings, infielder.)

For several days, Barnes played out the limited amount of slack he had to work with. He had missed his originally scheduled departure of February 19 from New York because of his holdout status. On the next day, he wired the team to advise them that he planned to report as instructed—which team officials took to mean that he had signed and sent in his contract. Upon arrival in Marlin, when it became clear that he still had not signed, Hugh Jennings issued an ultimatum on behalf of the team: either sign the contract or be cut from the team roster. When Barnes countered that he had never received notification of the team’s ban on unsigned players (although he acknowledged that Zeke had received a telegram to that effect), Jennings presented the issue to Charles Stoneham, president of the Giants, for guidance. The reply came quickly. The ban was to be strictly applied, and Barnes was no exception. Left with little option, Barnes signed the contract and began workouts with his batterymates. One by one, the Giants players fell into line, and the team prepared to defend its championship title.

“Down the River”

The Giants’ prospects looked good at the beginning of the 1923 season. The team had exceptional assets in the prowess of its infield and the firepower of its offense. The principal concern continued to be the pitching staff, despite its impressive performance in the 1922 World Series. Barnes’ role on the team was no longer a central consideration—his career was regarded as “nearing the end”—and, as it transpired, he had but 36 innings left in a Giants uniform.

On May 18, 1923, right-hander Jack Scott fractured a small bone in his pitching hand when he was struck by a batted ball during pregame warm-ups. He was expected to be sidelined for up to six weeks, a blow to the Giants since he was a key figure in the starting rotation, having already won five games. At the time of the injury, the team topped the league standings with a 3½ game lead over the Cardinals.

To keep the Giants in the thick of the pennant chase, McGraw took action to address the void left by Scott’s absence. The deal he struck—a straight-up exchange of Barnes and catcher Earl “Oil” Smith for Boston Braves pitcher John “Mule” Watson and catcher Hank Gowdy—was announced on June 7. McGraw, in informing Barnes and Smith of the trade, reportedly told them, “You’re going down the river—you’re headed for Boston.”35 On the day of the trade, Barnes made his last appearance for New York; he picked up a loss in two innings of relief against the Cubs in Chicago. When the Giants left the Windy City, Barnes and Smith stayed behind to suit up for their second consecutive series against the Cubs, this time donning less prestigious colors.

Being traded probably was not a total surprise to Barnes—the injury to Scott may have done little more than influence the timing and the particulars. Still, moving from the league-leading, reigning champion to a near tailender, 16 games removed from first, must have required some getting used to. Swagger rights were gone, as were the Giant standards for player amenities.

The trade became something of a precipitating factor in a legal petition filed in the fall of 1923 by a group of Boston citizens who requested an investigation of the Red Sox and Braves ownership and their respective relationships with the Yankees and Giants. The investigation did not materialize, but the petition gave brief voice to long-held suspicions that there were “irregularities” in the relationships between the two pairs of teams, given the many trades over the years that on balance favored the New York clubs.

Whether the Barnes-for-Watson swap gave the Giants an advantage is, in retrospect, debatable. During the balance of the 1923 season, Barnes had more wins than Watson (10 vs. 8), and he had a better ERA (2.76 vs. 3.41). True, he had significantly more losses (14 vs. 5), but he played for a team that finished 41½ games behind the Giants. Watson started Game One of the World Series for the Giants, but he pitched only two innings and allowed three earned runs. Although younger than Barnes, Watson lasted only one more year in the major leagues, going 7-4 for the Giants in 1924.

Barnes would spend two and a half seasons in Boston during his second run with the Braves; in 100 appearances he had 83 starts, 50 complete games, and 36 wins. Deep in the twilight of his major league career, he nonetheless compiled a creditable record in 1924. Just as he had in 1917, Barnes became the workhorse for the Braves in 1924. He had an ERA of 3.23 and led the team in wins (15), complete games (21), shutouts (4), and innings pitched (267 2/3). Most notably, he completed the 1924 season without a wild pitch or a hit batsman, and still holds the National League record for the most innings worked by a pitcher to have accomplished that feat.36

For the second time in his career, Barnes also led the team and the league in losses, with 20. The 1924 Braves finished last in the league with 100 defeats, largely because of the team’s anemic offense. At .256, the team batting average was 44 points lower than the league-leading Giants and 19 points below the Phillies, the club with the second-worst batting average. In 11 of Barnes’ 20 losses in 1924, the team was either shut out or scored only one run.

Barnes’ work in 1924 wasn’t completely obscured by his team’s claim on the cellar. Burt Whitman, sportswriter for the Boston Herald and The Sporting News, regarded the veteran as still being “one of the very best pitchers in either league.” Whitman and others reported that Barnes retained the respect of National League managers, some of whom ranked him high among the league’s pitchers “when smartness and stuff both are taken into consideration.”

Less welcome media attention came during a road stop in Cincinnati midway through the 1924 season, when news of Barnes’ off-the-field activities spilled onto the sports page. Rain had forced cancellation of the Braves-Reds game scheduled for July 14, so some of the Braves players decided, Prohibition notwithstanding, to turn the unexpected downtime into a party marathon that extended well beyond midnight. Hours into the revelry, the fun deteriorated into something else, triggering angry outbursts that led to a “free-for-all” involving five or six Braves players. The Cincinnati Enquirer reported the principal antagonists to be Barnes and catcher Mickey O’Neil, both of whom brought visible signs of injury with them to the ballpark for the next day’s game. O’Neil sported a black eye and damage to his chin and jaw. Barnes suffered from a sprained or dislocated thumb and was unable to make his scheduled start.

The 1924 season also marked the beginning of the Barnes vs. Barnes matchups when, on May 2 in Boston, both Jess and Zeke entered the same game in relief. They were not the first brothers to appear in the same major league game, but when they were each handed the ball on June 26, 1924, in New York City, the Barnes brothers became the first pair to oppose each other as starters.37 Jess took the loss in the Braves’ 8-1 defeat by the Giants, but Zeke did not figure in the decision. Altogether, the brothers would share opposite-team box score billing 10 times in their major league careers, including five instances when they both started for their respective teams. Of the 10 joint appearances, Jess won five and lost three, while Zeke won three and lost four. Zeke pitched for the Giants in all 10 contests. Jess appeared six times for the Braves, and four times for the Robins.

In addition to their same-game appearances, the brothers brandished both their family and team colors by winning their respective halves of a doubleheader in Boston on September 1, 1924. In the first game, Jess went the distance on the mound, hit safely in two of his four at-bats, and drove in three runs for the Braves, who prevailed by a score of 5-4 in 11 innings. Zeke had an easier time in his complete-game outing for the Giants, who took the second game by a score of 10-2. He also had a good day at the plate, going 2-for-4 and scoring two runs.

Not a great deal is known about the relationship between the two brothers, but they seem to have been close. They spent time together in Kansas during the offseason, occasionally playing town team ball or even basketball. Both were avid outdoor sportsmen, and they especially loved to hunt. Evidence of their marksmanship comes through in a family story about a recreational outing to an arcade, probably in the New York area, that included a stop at the arcade’s shooting gallery. Jess and Zeke wore out their welcome by cleaning out the gallery’s prizes, and were barred from ever returning.

Jess had helped open major league doors for Zeke, but there also must have been some good-natured rivalry once they found themselves on opposing teams. If Zeke’s comments to Jess following a win in 1925 are any indication, there were mild taunts when one or the other prevailed in a head-on contest: “I thought you were going to show me how to pitch…when you’re not busy come around and I’ll show you how to twist them…” 38

Boston retained Jess through the 1925 season, when his record dipped to 11-16 with an ERA of 4.53. In October of that year the Braves announced that he had been traded to Brooklyn, along with outfielder Gus Felix and catcher Mickey O’Neil of the Cincinnati scrum. In return, the Braves acquired catcher Zach Taylor, infielder Jimmy Johnston, and outfielder Eddie Brown.

As Barnes moved through his 1926 and 1927 seasons with the Robins, it became evident that the major league ride was nearly over. In 1926, his total innings fell to 158 while his ERA soared to 5.24; during his four-month season in 1927, he pitched only 78 2/3 innings, had a 5.72 ERA, and won but two games. Although his arm had been the intermittent question mark during his career, an interview-based article late in Barnes’ life suggests that ailing knee joints were a factor in the gradual breakdown of his pitching mechanics.39

A Step Down, Then Out

Just two days before his thirty-fifth birthday, on August 24, 1927, Brooklyn gave Barnes his unconditional release. Even though he had cast a faint shadow near the end of his career, there was some show of support in the media at the time of his departure. One writer, Eddie Murphy, felt that Barnes’ performance had suffered because he had been underused, that he was a pitcher who needed steady work to be at his best. Thomas Rice, sportswriter for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle and columnist for The Sporting News, wrote that it was a “pity” that no major league club claimed Barnes through the waiver process.

His knees and/or arm may no longer have passed major league muster, but they were still good enough to earn him a paycheck, and this time, Barnes arranged for his own transition to a new clubhouse—after having requested and received permission from Brooklyn manager Robinson to explore opportunities with other teams. At the same time his release from the Robins was announced, it was reported that he had signed with the Toledo Mud Hens, the American Association team managed by his former teammate Casey Stengel.

When Barnes joined the 1927 Mud Hens, the team was on its way to securing the American Association title for the first time in franchise history, and the race was a nailbiter. At the start of action on the final day of the season, three teams remained in contention—Toledo, Milwaukee, and Kansas City. Toledo emerged victorious by sweeping a doubleheader with Indianapolis, which placed the Mud Hens two games ahead of both Milwaukee and Kansas City in the final standings. The championship entitled the Mud Hens to represent the league in the “Junior (or Little) World Series,” the annual duel between the titleholders of the American Association and the International League.