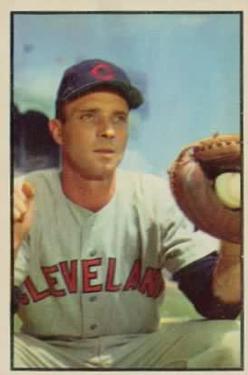

Jim Hegan

The Cleveland Indians of the early 1950s, including the 1954 team, were well known for their Big Four starting rotation, consisting of Bob Feller, Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, and Mike Garcia. But when asked which superstar pitcher was the best, Yankees manager Casey Stengel said, “Give me that fella behind the plate. He’s what makes ’em.”[fn]Hal Lebovitz, “Trade will help Cavaliers – if Turpin has heart,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 20, 1984. [/fn]

The Cleveland Indians of the early 1950s, including the 1954 team, were well known for their Big Four starting rotation, consisting of Bob Feller, Bob Lemon, Early Wynn, and Mike Garcia. But when asked which superstar pitcher was the best, Yankees manager Casey Stengel said, “Give me that fella behind the plate. He’s what makes ’em.”[fn]Hal Lebovitz, “Trade will help Cavaliers – if Turpin has heart,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 20, 1984. [/fn]

Stengel was referring to Jim Hegan, the Indians’ longtime catcher, who had a reputation for excellent defense. Hegan’s catching prowess and game-calling ability helped the Tribe have one of the game’s most dominant pitching staffs from 1947 to 1956. Beyond his success on the field, Hegan was one of the Indians’ most popular players, among both his teammates and the Cleveland fans. He spent 14 of his 17 major-league seasons with the Indians and never lacked for job security despite a career batting average of just .228.

James Edward Hegan was born on August 3, 1920, in Lynn, Massachusetts, a few miles north of Boston, to John and Laura Hegan, a working-class Irish couple. His father was a policeman. Family was the focal point of the Hegans’ lives. John sang in a barbershop quartet, and any time they were all together after dinner, they would gather to sing in the living room. Emphasis on family and an affinity for barbershop quartets remained with Jim for the rest of his life.

The Hegan family – Jim had two sisters and four brothers – also possessed a substantial amount of athletic ability. Jim’s youngest brother, Larry, played basketball and pitched for his high-school baseball team despite having a deformed hand. His oldest brother, Ray, was a very good football player and received a scholarship to Dartmouth.[fn]Interview with Mike Hegan, August 12, 2009.[/fn] Jim starred in baseball, basketball, and football in high school. He was the only one in his family to play a sport professionally.

“He was a tremendous, all-around athlete,” said Hegan’s son, Mike, who followed his father into baseball, had a 12-year major-league career, and has been a play-by-play broadcaster for more than three decades. “He quit playing football in his sophomore year because I think he knew he wanted to play baseball professionally. My mother and others have told me that he was an outstanding receiver in football.” Mike said his father was a center in basketball and played semipro in the offseasons in Boston for a forerunner of the Boston Celtics, before the NBA was created.[fn]Thanks to Mike Hegan for supplying much of the information regarding Jim’s family background.[/fn]

Hegan met his future wife, Clare, at Lynn English High School. He was a senior and she was a sophomore. It took little time for them to realize that they wanted to get married, and they were wed in 1941.

Jim and Clare had three children, Mike, Patrick, and Catharine. Mike was the oldest, born in 1942, seven years before his brother, Patrick, and 12 years before his sister, Cathy. Mike played for three teams during a 15-year playing career before becoming known to another generation of Indians fans as a TV and radio broadcaster for Indians games.

Like most young families, the Hegans had to work hard to make ends meet. Before moving from Boston to Cleveland, the family shared a house with Clare’s sister, across the street from Clare’s parents.

“My dad was very much a family man,” Mike said. “He puttered around the house. Even when he was semi-retired, he and my mom spent a lot of time together, shopped together, and vacationed together. He had good friends, but they were basically his family. Family was most important to him.”[fn]All additional quotations from Mike Hegan come from the 2009 interview.[/fn]

Hegan broke into professional baseball in 1938, when the Indians offered him a contract at the age of 17.[fn]Hal Lebovitz, “Hegan has gone, but leaves us memories of a truly class act,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 19, 1984, 1-D.[/fn] He played in the minor leagues with Springfield of the Class C Middle Atlantic League in 1938 and 1939, and split the 1940 season between Oklahoma City of the Texas League and Wilkes-Barre of the Eastern League. He played for the same two teams in 1941, and was promoted to the Indians in September. His debut with Cleveland, on September 9 against the Philadelphia Athletics, must have been a daunting event for Hegan; he was assigned to catch Bob Feller. But the rookie went 2-for-5 with a home run and drove in three runs, and the Indians won, 13-7, as future Hall of Famer Feller earned his 23rd victory of the season.

After the game manager Roger Peckinpaugh told Hegan, “Nice game,” which Hegan later said was “like handing me $1 million.”[fn]Ibid.[/fn] Sportswriters were equally complimentary; the Cleveland Plain Dealer said that “although Feller is one of the most difficult pitchers in the major leagues to catch, Hegan handled him perfectly and performed like a veteran.”[fn]Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 10, 1941.[/fn]

Hegan’s debut was a sign of a promising career to come, although the realization of that career took some time. In 1942 he played in 68 games and batted only .194 in 170 at-bats as Otto Denning and Gene Desautels handled the bulk of the catching. With the US fighting in World War II, Hegan was away serving in the Coast Guard from 1943 through 1945. He returned to the Indians in 1946 and batted .236 in 271 at-bats while splitting the catching duties with Sherm Lollar and Frankie Hayes.

Hegan became the starting catcher in 1947, though he was hobbled by manager Lou Boudreau’s decision to call the pitches from his position at shortstop. That angered the pitchers and stung Hegan, though he advised the pitchers not to rebel. The Indians went 80-74 but didn’t fulfill expectations. Owner Bill Veeck nearly fired Boudreau as manager.[fn]Lebovitz, “Hegan has gone,” 3-D.[/fn]

Before the 1948 season Boudreau told Hegan to forget about the previous season and gave him the duty of calling pitches. The Indians posted a team ERA of 3.22, leading the American League, and proceeded to win the pennant and World Series. Perhaps Boudreau’s demonstration of confidence boosted Hegan’s offensive production; he had his best season with the bat, hitting .248 with career highs in home runs (14), RBIs (61), and doubles (21). He finished 19th in the American League Most Valuable Player voting, ahead of notable players like teammates Feller and Larry Doby and fellow catcher Yogi Berra of the Yankees. (Boudreau won the MVP award.)

After the Indians defeated the Braves in the World Series, team owner Veeck praised Hegan, saying, “There isn’t a better catcher in the league.”[fn]Associated Press, “Veeck Contemplates Few Changes In Indians’ Squad for 1949 Season,” New York Times, October 15, 1948, 29.[/fn] Judging from Indians pitchers’ performance during Hegan’s years as the everyday catcher, few could argue with Veeck. From 1947 to 1956 the Indians led the American League in ERA six times. In those ten years a Cleveland pitcher won 20 games 17 times. Hegan caught three no-hitters, one of only 14 catchers to do so, as he was the receiver for Don Black’s no-hitter in 1947, Bob Lemon’s in 1948, and Bob Feller’s third in 1951. (One of the 14, Jason Varitek, caught four.)[fn]Mike Petraglia, “No-hitter a record fourth for Varitek,” available at http://mlb.mlb.com/news/article.jsp?ymd=20080519&content_id=2733852&vkey=news_mlb&fext=.jsp&c_id=mlb[/fn]

The most spectacular pitching staff during Hegan’s tenure, of course, was the one from the 1954 team. That year, the Indians led the American League with a sparkling 2.78 ERA. With such a dominant staff leading the way to a 111-win season, losing the World Series in a four-game sweep to the Giants was hard to take, particularly for Jim.

“The 1954 year might have been the most satisfying and the most frustrating for him, simply because they won 111 games but didn’t win it all,” Mike Hegan said. (The Indians were swept by the New York Giants in the World Series.) “They were not the best baseball team, yet they were. All those guys from that team just kind of shake their heads. It just might have been a quirk of fate, the way it worked out.”

The Hegans relocated permanently to Cleveland in 1954 after spending offseasons in the Boston area. The family moved to their new home in Lakewood, just west of the city, and Hegan joined in a business venture with Cleveland Browns quarterback Otto Graham. Eventually they opened a store, Hegan-Graham Appliance, on Euclid Avenue in downtown Cleveland that sold sporting goods, luggage, and jewelry in addition to appliances, and urged customers to “Get the right pitch before you buy.”[fn]Joe Wancho, “Mike Hegan,” The Baseball Biography Project, available at http://bioproj.sabr.org/bioproj.cfm?a=v&v=l&bid=1681&pid=6068.[/fn]

Hegan made several noteworthy headlines during the 1954 season. One memorable day was September 12, when the Indians swept a doubleheader against the Yankees before a crowd of 86,563 at Cleveland Stadium. Hegan caught both games, a complete-game 4-1 victory for Bob Lemon and a complete-game 3-2 victory for Early Wynn. Six days later he hit a solo home run for what turned out to be the deciding run in the pennant-clinching victory in Detroit.

The headlines weren’t as favorable in Game One of the World Series against the Giants at the Polo Grounds in New York. In the eighth inning, with the score tied at 2-2 and two Indians on base, Willie Mays made his famous catch of Vic Wertz’s long drive to center. Most people say the catch took the wind out of the Indians’ sails. In reality, the Indians had a better chance to score three batters later, but the wind literally ruined their chance to score. Hegan came to bat with the bases loaded and two outs and hit a long fly to left, but the wind knocked down what might have been a grand slam.

“It looked like a homer, but the wind, blowing toward the right, pulled the ball in so that Monte Irvin was able to make the catch,” Indians manager Al Lopez said after the game.[fn]Louis Effrat, “Cleveland Contends Wind Contributed to Downfall at Two Important Points, New York Times, September 30, 1954, 41.[/fn] Irvin said, “[The ball] was out of my sight. Gone. It missed the scoreboard by a fraction of an inch and fell into my glove.”[fn]Lebovitz, “Hegan has gone,” 3-D.[/fn]

The same wind didn’t do the Indians any favors in the bottom of the tenth, when Dusty Rhodes’ short fly ball stayed fair down the right-field line for a three-run homer, giving the Giants a 5-2 victory and setting the stage for their sweep.

That 1954 season was one of Hegan’s best. He batted only .234 but hit 11 home runs and a career-high seven triples, and led American League catchers in fielding percentage (.994). He repeated the feat in 1955 (.997) while committing only two errors.

At 33 Jim was entering the latter stages of his career. He had two more seasons as the Indians’ regular catcher. In each of those seasons the Indians finished second to the Yankees, just as they had done each season from 1951 to 1953. Hegan had established himself as one of the most popular players on the team. In 1953 he was honored with a Jim Hegan Night at Municipal Stadium. Little League catchers wore his uniform number, 10, and when he switched to 4, they switched too.[fn]Lebovitz, “Hegan has gone,” 1-D.[/fn]

Hegan was popular with his teammates too. Often they would join him in barbershop quartets on train rides during road trips. Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Lemon was his roommate and best friend. They roomed together for 17 years, starting in the minor leagues when they were both 18. The two were complete opposites. Lemon was an avid socializer who loved to crack jokes and often came in late after having a few too many. Hegan was more reserved and was one of the few players who didn’t drink.

“Lem was always so full of fun,” Clare Hegan once said. “He’d wear a fake arm and shake somebody’s hand and the arm would come off. Jim was quiet. He was dignified, even when he was young. He was almost embarrassed when people recognized him as being a major leaguer.”[fn]Bob Dolgan, Heroes, Scamps and Good Guys (Cleveland: Gray & Company, 2003),, 35.[/fn]

“You couldn’t have two any more different personalities,” said Mike Hegan. “People used to say that they would invite Jim out with the guys after the ballgame because he would make sure they would get home. He was this day and age’s designated driver.”

With young catcher Russ Nixon waiting in the wings, the Indians traded Hegan to Detroit before the 1958 season. After brief stints with the Tigers, Philadelphia Phillies, and San Francisco Giants in 1958 and ’59, Hegan’s playing career seemed to be over. He and Otto Graham had closed the appliance business after Graham went to the Coast Guard Academy to coach football. Hegan then went to work as a salesman for a trucking company. But in the spring of 1960 he got a call from his old manager, Lou Boudreau, who was now managing the Chicago Cubs. One of the Cubs’ catchers, Dick Bertell, was injured, and Boudreau wanted Hegan to join the Cubs as a backup catcher. After discussing the opportunity with Clare, he accepted Boudreau’s offer. “I was a senior at St. Ignatius (in Cleveland) at the time, and the two of us would go up to Lakewood Park with a bag of balls,” Mike said. “I threw him batting practice every day for about a week. After the Cubs returned from a road trip, he joined the team.”

Hegan played his first game for the Cubs on May 28 and hit a home run in his second at-bat. But he played sparingly, and the Cubs released him on July 27. Hegan quickly signed with the Yankees as a bullpen coach to replace Bill Dickey, who was ill. Dickey had been a Hall of Fame catcher with the Yankees and had once famously said of Hegan, “When you catch like Hegan, you don’t have to hit.”[fn]Al Doyle, “Sustaining a Long Career: Despite weak hitting abilities, some catchers make an impact in the major leagues strictly on their defensive expertise,” Baseball Digest, October 1996, 57.[/fn]

The Yankees placed Hegan on their active roster in September. Though he didn’t appear in a game, manager Casey Stengel still thought highly of Hegan’s ability, telling the New York Times, “Hegan still is a very fine catcher, especially in moving around and getting under foul balls.”[fn]John Drebinger, “Fisher in 7-hitter,” New York Times, September 4, 1960, 129.[/fn]

After Ralph Houk replaced Stengel in 1961, Hegan remained with the Yankees. He coached with the team for 16 seasons, from 1960 to 1973 and in 1979-80. As of 2012 he had the third longest tenure among Yankees coaches, trailing only Frank Crosetti (1946-1968) and Jim Turner (1949-1959, 1966-1973).[fn]http://mlb.mlb.com/nyy/history/coaches.jsp[/fn]

Mike Hegan played for the Yankees in 1964, 1966, and 1967. During their time together Jim almost joined Mike on the active roster. “There was one year when somebody got hurt and there were some rumors of activating my dad,” Mike said. “But he didn’t want to do it, and it wasn’t because I was on the team. Had that happened, we would have been the first father-and-son combination to play on the same team.” Ken Griffey, Jr. and his father, Ken Sr., became the first, playing together on the Seattle Mariners in 1990. Still, the Hegans achieved a couple of feats rare for father-son duos. They each played on a World Series-winning team, with Jim playing for the 1948 Indians and Mike for the 1972 Oakland Athletics. They were the first father-and-son tandem to be chosen for the All-Star Game; Jim was picked five times and Mike once.[fn]http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/all_star_event.jsp?story=16[/fn]

“I was able to watch him in action and operate,” Mike said. “He was really Ralph Houk’s right-hand man. Everywhere Ralph went, he went. I would call him an assistant pitching coach more than anything else. That’s basically what he was.

Mike said he didn’t receive favorable treatment from his father while with the Yankees. “He was the same in his relationships with players, whether they were teammates or from a coaching perspective, or even a parenting perspective. He was always consistent.”

Mike said his father’s personality and tall stature helped make him an effective coach. “For that age, he was kind of a big guy, 6-3 or 6-4 (he was 6-feet-2, according to Baseball-reference.com), so he had a commanding presence,” Mike said. “He didn’t say much, but when he did say something, you took the hint. That’s the way he was. If you were to talk to guys like Feller and Lemon over the years, that’s the way he was behind the plate as well. Everybody said that he was a very strong leader.”

Jim died at the age of 63 on June 17, 1984, after a heart attack. His legacy for defensive excellence at the catcher position remains well intact. His teammates marveled at his ability. “He was so good that if you crossed him up nobody knew it,” Herb Score recalled after Hegan died. “He had the best hands I ever saw. If I crossed him up he might not tell me until three days later.”[fn]Lebovitz, “Hegan has gone,” 3-D.[/fn] Mike Garcia once said of him, “If a foul ball went in the air and stayed in the ballpark it was an automatic out. He didn’t stagger around under it. He went right to the spot of the ball.”[fn]Ibid., 1-D.[/fn]

Mike Hegan said his father took pride in his game-calling and defensive ability. “He took pride in that aspect of the game, knowing it was a strength,” Mike said. “He was a great athlete, and that transferred behind the plate in his ability to catch the baseball, block balls, and have an outstanding throwing arm. People still say he never dropped a pop fly behind home plate. Bob Lemon shook him off once. The batter then hit a home run, and Lemon never shook him off again.”

Hegan’s love of the game and his drive to succeed undoubtedly helped him achieve his success. “He loved baseball,” Clare once said. “He couldn’t believe people were paying him to play.”[fn]Dolgan, Heroes, Scamps and Good Guys, 34.[/fn]

“He was a perfectionist,” Mike said, and recalled when his father took up golf and joined Avon Oaks Country Club, west of Cleveland. “My dad started playing and gave it up because he grew frustrated that he couldn’t excel at it. If he couldn’t do something, he would walk away from it instead of being frustrated by it.”

Fortunately for Cleveland fans and Tribe pitchers, Jim Hegan loved baseball and perfected the art of catching. He continues to be and always will be remembered as one of the greatest and classiest players ever to wear a Cleveland Indians uniform.

This biography is included in the book Pitching to the Pennant: The 1954 Cleveland Indians (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), edited by Joseph Wancho. For more information, or to purchase the book from University of Nebraska Press, click here.

Full Name

James Edward Hegan

Born

August 3, 1920 at Lynn, MA (USA)

Died

June 17, 1984 at Lynn, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.