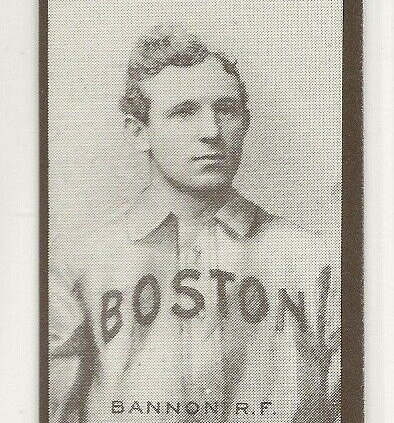

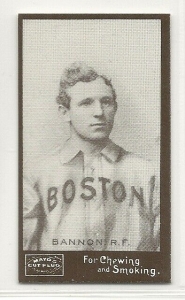

Jimmy Bannon

James Henry “Jimmy” Bannon was born on May 5, 1871, in Amesbury, Massachusetts. He grew up in Saugus, Massachusetts, where he played ball with his brothers Tom, George, and William. Tom Bannon also became a professional ballplayer and played two seasons with the New York Giants (1895, 1896). George and William never made it out of the minor leagues. Their parents, Patrick and Johanna (Conners) Bannon, were natives of Ireland. Patrick Bannon worked in a woolen mill at the time of both the 1870 and 1880 Censuses. There were 10 Bannon children at the time of the 1880 Census; James was the sixth-born.

James Henry “Jimmy” Bannon was born on May 5, 1871, in Amesbury, Massachusetts. He grew up in Saugus, Massachusetts, where he played ball with his brothers Tom, George, and William. Tom Bannon also became a professional ballplayer and played two seasons with the New York Giants (1895, 1896). George and William never made it out of the minor leagues. Their parents, Patrick and Johanna (Conners) Bannon, were natives of Ireland. Patrick Bannon worked in a woolen mill at the time of both the 1870 and 1880 Censuses. There were 10 Bannon children at the time of the 1880 Census; James was the sixth-born.

Bannon played minor-league ball for the Lynn, Massachusetts, team in 1891 and the Portland, Maine, team in 1892. (Both teams were in the New England League.) In 1893 Bannon pitched for the College of the Holy Cross baseball team, which finished the season with an 11-5 record.1

Bannon also played in 1892 and 1893 for the independent Northampton (Massachusetts) team, which played exhibition games against the Boston Beaneaters before large crowds at the Driving Park, as well as against the Louisville Colonels and St. Louis Browns.2

Bannon’s play as an outfielder and shortstop at Holy Cross had brought him to the attention of the Browns, and they signed him to a contract for the 1893 season. In his major-league debut, on June 15, 1893, he played right field in a 5-1 loss to the Boston Beaneaters. He played in 26 games for the Browns in 1893 and batted .336, with three doubles, four triples, and eight stolen bases. He also started one game on the mound for the Browns, pitching four innings in a loss in which he allowed 18 runs (10 earned).

Bannon played two games at shortstop early in his rookie season, committing seven errors in just two games, so manager Bill Watkins moved him permanently to the outfield. But he didn’t improve his defensive skills there; he made eight more errors in 24 games. Yet the New York Clipper said Bannon “became popular with the Mound City [St. Louis] enthusiasts on account of his hard and timely batting. When [St. Louis Browns] President Chris] Von der Ahe released him near the end of the season there was a storm of indignation, and his release was recalled, but it was finally decided to let him go for good, as Mr. Von der Ahe considered [Duff] Cooley, who was on his club’s pay rolls, to be as good, if not a better player.”3

According to the New York Clipper, several teams sent telegrams to Bannon expressing interest in him, “but somehow they did not reach him.”4 He learned of this upon returning to Boston, where he joined the Beaneaters for the 1894 season. He played in the outfield with future Hall of Famers Hugh Duffy and Tommy McCarthy. Bannon continued to hit well. He batted .336 with 130 runs scored and 114 runs batted in for the powerful Boston offense. But Bannon continued to struggle defensively. Although he led all National League outfielders with 43 assists, he was second in the league with 41 errors. (He did help turn 12 double plays, which was the NL record for most double plays by an outfielder in a season until Jimmy Sheckard of the Baltimore had 14 in 1899.)

One of the highlights of the season for Bannon came when he hit grand slams in consecutive games.5 The first came on August 6 in a 15-7 win against the Washington Nationals. The next day he hit another in the Beaneaters’ 19-8 win over the Philadelphia Phillies.

On May 15, 1894, the Beaneaters were playing the Baltimore Orioles at the South End Grounds, which Sporting Life had described as the “handsomest in the country.” The structure had been repaired in the offseason, and workers had left sawdust and debris behind, under the right-field seats.6

After the end of the third inning, Bannon saw flames coming up through the right-field bleachers stands as he headed to the outfield and he ran to put it out. Wind caused the fire to flare up and Bannon tried without success to extinguish the fire with his feet. Soon, the right-field bleachers caught fire and eventually the outfield fence as well as the left-field bleachers went up in flames.

Quickly the fire spread from the ballpark to neighboring buildings. At least 12 acres were destroyed in the surrounding area and more than 1,900 people were made homeless by the fire,7 which became known as the the Great Roxbury Fire of 1894.8 The homeless Beaneaters moved to Boston’s Congress Street Grounds, which had hosted Boston Players’ League and American Association teams earlier in the decade.

After the season Bannon was offered a salary of $1,200 for 1895 by Beaneaters manager Frank Selee. Bannon initially refused to sign, claiming that he had earlier been offered a raise for the 1895 season.9 He eventually signed on the condition that he receive the raise or be released from his contract.10 The team signed him, raised his salary on June 1 and Bannon played the entire season with the Beaneaters.

Bannon continued to be a productive hitter in 1895, batting a career-high .347 with 74 RBIs. Several times during the season, he led the Beaneaters to victory. Sporting Life described one series where Bannon played a key role in consecutive wins for the Boston team: “If any one player owned a town, Bannon owns Boston. Few batting feats will compare with those of his last week. On Tuesday he made three hits. On Thursday he went to bat nine times and made eight hits, besides making a timely sacrifice. Friday morning, with Lowe on first base and St. Louis one ahead, he sent the ball over the left field fence, there being two out at the time and one man on base and the game was won. In the afternoon he made a home run again and hit safely every times [sic] he came to bat. On Saturday Cincinnati led in the seventh inning until he came to the rescue with another home run. Naturally he led the team in batting at the close of the week, both in singles and in totals. He made 13 hits in the four games.”11 During the season, Bannon was credited with hitting safely in 21 straight games.12

Bannon slumped badly in 1896. His batting average dropped to .253 and he had only 87 hits before the Beaneaters dropped him in August. His poor fielding may have also led the team to consider Bannon a liability. The Boston Globe commented that “good base running and line throwing do not altogether offset miserable fielding.”13 Playing in in the outfield as well as around the infield, he had 29 errors when he was released on August 18. Sporting Life wrote that the Pittsburgh team was interested in him but Boston did not immediately release their claim on Bannon. He never signed with another major-league team.14

In four years, Bannon played in 367 major-league games and batted .320. His fielding percentage was a meager .877 and he had made 98 errors as both an infielder and outfielder.

After being released by the Beaneaters, Bannon became a journeyman minor leaguer. He moved to a new team almost every year through 1910. He split the 1897 season between the Kansas City Blues (Western League) and Springfield Ponies/Maroons (Eastern League), and batted a combined .327 with 41 doubles and 66 stolen bases. Bannon started the 1898 season with Springfield, but later moved to the Montreal Royals in the same league. He was dropped near the end of the season, according to Sporting Life. There was speculation that the club didn’t want to pay him since he was a “high priced man” due to his prior major-league experience.15

In February 1898 Bannon married Mary Elizabeth O’Brien in Lynn, Massachusetts. The couple had two children, Lucas and Lauretta.16

Bannon played for the Toronto Maple Leafs in the Eastern League from 1899 to 1902. He batted a career-high .341 in 1899 and stole 44 bases. He batted over .300 the next two seasons, too. But Sporting Life noted in May 1902 that Bannon was batting left-handed and that he had made the change on “account of the poor luck he had” at the plate during the prior season.17

Bannon played for the Columbus Senators in the American Association in 1903 but returned to the Eastern League in 1904, playing for a different team in the league every year until 1907. Bannon’s stops included the Newark Sailors, Montreal Royals, and Rochester Bronchos (two separate years). He never had the same hitting success that he experienced earlier in his career.

By 1908 Bannon’s skills as a player had begun to decline severely. He spent the next three years playing in the Class-B New York State and New England Leagues. Each year saw Bannon playing in fewer games as he continued to see his batting average slide lower and lower.

Bannon managed teams in five different seasons before he quit professional baseball. His first job was managing the Columbus (Ohio) Senators in 1903. Bannon also spent two years as player-manager for the Montreal Royals as well as the Binghamton (New York) Bingoes of the New York State League. His greatest success as a player-manager came in 1908 when he managed the Bingoes to a second-place finish. He managed the Lawrence (Massachusetts) Colts of the New England League in 1910; his final stint as a manager was in 1911 with the Haverhill (Massachusetts) Hustlers, also of the New England League.

By the time Bannon finished his playing career, he had earned the nickname of Foxy Grandpa. As early as 1902, he was referred to by Sporting Life as the “white haired” Jimmy Bannon.18 The Wilkes-Barre Record wrote on February 8, 1906, that “the gray haired youngster, known from coast to coast as Foxy Grandpa, will manage the Montreal club in the Eastern League. Bannon isn’t as old as he looks by twenty years because his hair is prematurely gray.”19

After he left baseball, Bannon bought the Rochester, one of the largest hotels in Rochester, New Hampshire.20 He ran the hotel for many years before selling it and moving to New Jersey. Bannon was elected to the New Hampshire legislature in 1912. Sporting Life described his election as follows: “Coming from a progressive family whose members cannot be kept down because of dash, and energy, Jimmy goes to the legislature to learn new fields and new duties. His friends say that no one was more surprised than Bannon.”21

Bannon died in March 24, 1948, at the age of 76. He was living in Glen Rock, New Jersey, at the time. He was buried in St. Mary’s Cemetery in Rochester, New Hampshire.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also utilized the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for box scores, player, team, and season pages, pitching and batting game logs, and other material pertinent to this biography.

Notes

1 “2015 Holy Cross Baseball Record Book,” goholycross.com/fls/33100/import_content/sports/m-basebl/archive_files/Record_Book/2015_Record_Book_w-out_All-Time_Results.pdf, accessed March 8, 2017.

2 “Northampton Baseball III: 1890’s – Independent Baseball in Northampton,”

historic-northampton.org/highlights/baseball3.html.

3 “James Bannon,” New York Clipper, November 16, 1895: 587.

4 Ibid.

5 John C. Tattersall, “The Grand Slam Story,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1975, accessed March 9, 2017.

6 Bob Ruzzo, “Baseball Is Back: An Unexpected Farewell: The South End Grounds, August 1914,” https://bostonbaseballhistory.com/an-unexpected-farewell-the-south-end-grounds-august-1914/, April 4, 2014.

7 Ibid.

8 “The Great Roxbury Fire of 1894,” GoodOldBoston.Blogspot.com, May 12, 2013.

9 “Merry Montreal Will Not Lose Her Franchise in Eastern League,” Sporting Life, March 23, 1895: 8.

10 “Hub Happenings: The Boston Team Work So Far Satisfactory,” Sporting Life, May 4, 1895: 5.

11 “Hub Happenings: The Ex-Champions are Now Playing and Drawing Well,” Sporting Life, June 8, 1895: 5.

12 “James Bannon.”

13 “Baseball News and Comment,” Sporting Life, May 16, 1896: 5.

14 “League Bulletin,” Sporting Life, August 29, 1896: 5.

15 “Pittsburg Points,” Sporting Life, September 17, 1898: 9.

16 The spelling may or may not have been the idiosyncratic rendering of Loretta by the census enumerator.

17 “The Populous East,” Sporting Life, May 13, 1902: 8.

18 “Roused a Tartar,” Sporting Life, November 22, 1902: 13.

19 Wilkes-Barre Record, February 8, 1906.

20 Albert Spink, The National Game (St. Louis: National Game Publishing Company, 1910), 27.

21 “Bannon’s Rise,” Sporting Life, November 23, 1912: 15.

Full Name

James Henry Bannon

Born

May 5, 1871 at Amesbury, MA (USA)

Died

March 24, 1948 at Glen Rock, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.