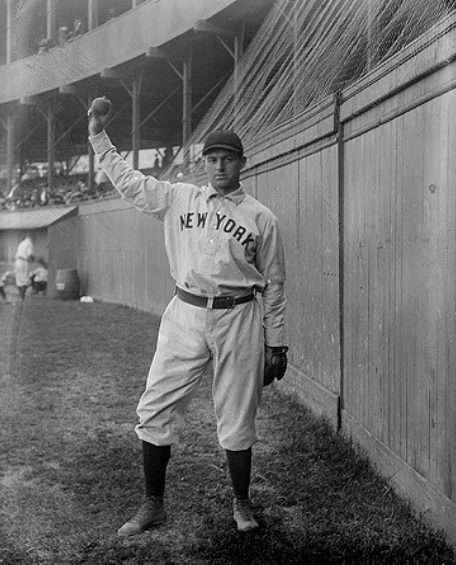

Joe McGinnity

One could make a strong case for Joe McGinnity being the most durable pitcher in baseball history. In just 10 seasons in the major leagues, “Iron Man” McGinnity worked 3,441 innings and won 246 games. During the month of August in 1903, he pitched and won both ends of a doubleheader three times; he accomplished the feat two other times in his career. He pitched another 3,821 innings and won another 235 games in a minor-league career both before and after that one glorious decade in the majors.

And to his dying day in 1929, Joe McGinnity couldn’t quite fathom why so many other pitchers weren’t just as durable as he was.

In May 1926, less than a year after throwing his final pitch in an organized game, he was serving as the pitching coach of the Brooklyn Dodgers. He lamented that major-league teams sometimes felt the need to have as many as 10 pitchers on their rosters. He thought they really only needed four or five.

“This policy has had a psychological effect upon the pitchers,” McGinnity said in an interview with the United Press. “They have been influenced into the belief that they should not have to work without a long rest and that they can’t be effective without that rest.”1

McGinnity seldom rested for very long. That applied to nearly every aspect of his life in and out of baseball. His 6½-season stay with the John McGraw-led New York Giants was his lengthiest tenure in any location or with any team.

McGinnity, who was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame posthumously in 1946, was a living, breathing paradox in many ways.

Although he was one of the biggest men in the major leagues at the dawn of the 20th century, at 5-foot-11 and 206 pounds, he was hardly a power pitcher. In his prime years, he relied almost exclusively on a baffling, rising curve ball that was so dear to him he gave it a nickname, “Old Sal.” He used a peculiar underarm pitching style but also sometimes threw a devastating sinker with a more conventional overhand motion. John McGraw often said he thought the use of two radically different pitching motions may have lessened the strain on his arm and contributed to making him so durable. He said that when pitching his doubleheaders, McGinnity would sometimes throw one game overhand and work the other game with underarm motion.

“It was as different as if two pitchers had been working,” McGraw said.2

McGinnity also mixed in a healthy dose of guile and an almost unmatched understanding of how to manipulate batters. He occasionally blended in a spitball, was expert at using the quick pitch, and never hesitated to brush back a hitter who stood too close to the plate. His 40 hit batsmen in 1900 are still the major-league record.3

He also loved to get inside the head and under the skin of opponents.

“He was a close second to McGraw when it came to needling players,” Ed Burkholder once wrote in Sport. “When he was on the mound, an enemy baserunner was in a constant state of nerves, and his bantering with the batter in the box contributed much to his success.”4

Legendary manager Connie Mack described simply described McGinnity as “a magician,” noting that “he knew all the tricks for putting a batter on the spot.”5

McGinnity received almost no formal schooling as a child growing up in the coalfields of Illinois, but he was one of the most cerebral players of his time, charting and chronicling the strengths and weaknesses of opposing batters long before it became the norm. He probably was the first pitcher to actually keep a “book” on opposing hitters. He had a ledger in his locker in which he wrote down observations about hitters almost every day so that he had his own systemized accounting of opponents’ tendencies.

“It saves me a deal of trouble and unnecessary work, not to mention long chances,” he said in a 1916 interview. “I don’t have to try ’em out, like I’d have to if I didn’t have the book. When you’re trying a batter out to find his weakness you have to put a lot of stuff on the ball and tax your arm. The book saves me that trouble. It’s all there in black and white, gathered from personal observation and experience for the most part. I don’t trust to memory. Anyone is likely to forget, and a lapse of memory with three on in a tight game many times leads to a costly mistake.”6

In another interview during the prime of his career, McGinnity added: “I ascribe a great deal of my success to my ability to judge the players as they come to bat. The first principle of a successful pitcher is to give his opponents what they don’t want.” In the same interview, he said he very seldom tried to strike out a batter, adding “Every pitcher has eight men on his club to help him out. The secret of successful pitching is to keep the batters from hitting ‘em hard.”7

McGinnity was a contradiction in at least one other way: Although he was a fairly stoic, easy-going man off the field, he had a simmering temper that occasionally got him into trouble on it. He undoubtedly was influenced by the combative McGraw and feisty John McCloskey, his first minor-league manager, and his career was littered with scuffles and scraps. In 1901, he was suspended for 12 days after physically assaulting umpire Tommy Connolly. He engaged in a wild, on-field fistfight with Pittsburgh’s Heinie Peitz in 1906, for which he was briefly jailed and eventually suspended for 10 days. In a nomadic trek through the minor leagues following his major-league career, there were dozens of similar incidents.8

“McGinnity was always known as a fighter,” the Dubuque (Iowa) Telegraph Herald reported. “When he entered a ballgame he had but one objective in mind — a victory. He was aggressive. He fought for his team and a player who did not show a disposition to fight for the club had no place in Joe’s heart. There were times when many thought he went too far with his aggressiveness. But that was McGinnity’s style of play and it won him ballgames. Off the field he was a different type of man, but once in that uniform he was all baseball, first, last and all the time.”9

Pat Wright, an old friend of McGinnity’s and his manager with Peoria in 1898, simply said he was “a hard player. He was a hard loser. He will fight to the last. He always did. He will not give up.”10

If all that wasn’t enough, McGinnity was a respectable hitter and was regarded by some as the best fielding pitcher of his era.

“I have never seen a pitcher with more confidence in himself than McGinnity had,” Hughie Jennings said. “He was so cocksure of his fielding ability that he would take any sort of chance, throwing to any base under any circumstance, and this fielding ability lifted him out of many tight spots.”11

He was born Joseph Jerome McGinnity on March 19, 1871, to Peter and Hannah McGinnity. For more than a century, it was believed and widely reported that he had been born in Rock Island, Illinois, but his birth actually took place about 30 miles east of there in Cornwall Township, a rural area of Henry County covered with farmland and dotted with small coal mines.12 His father was an Irish immigrant and nomadic coal miner who moved his family around frequently to different areas.

When Joe was only four, the family relocated to Shawneetown in the southeastern part of Illinois. It was there, in 1879, that tragedy struck the family. Peter McGinnity was working as a muleskinner, driving a wagon through a mine, when he was crushed to death by a load of coal. His three oldest sons, including eight-year-old Joe, went to work in the mines in his place.13

The family continued to move around, seeking employment wherever new coal deposits were found. They moved to Springfield, Illinois, and then to Decatur, Illinois. In Decatur, McGinnity was introduced to a leisure-time activity that would define his life: baseball.

In 1889, McGinnity was on the move again, this time relocating to work the coal mines in McAlester in Indian Territory, which would later become the state of Oklahoma. He also continued to dabble in baseball, helping to found a town team that traveled around the region playing other teams in that corner of Oklahoma and even venturing into Texas and Arkansas.

He never really considered baseball as a career until yet another coal-mining tragedy occurred. This one happened at the end of the workday on January 7, 1892, when an explosion ripped through the Osage Company’s No. 11 mine in Krebs, just east of McAlester. McGinnity had been among the last men to exit the mine before the mishap occurred. He escaped injury but many of his friends were among the more than 100 co-workers who perished. It made him begin to consider other career paths and he started to view baseball as something that could become more than just a way to spend his off hours.

McGinnity made some pocket money pitching for a team in Van Buren, Arkansas, and that led him to earn a professional contract with the Montgomery Colts of the Southern League in 1893. He pitched well at times there for John McCloskey, but went only 15-20. In 1894 he was signed by the Kansas City Blues in the Western League. He had his ups and downs there, too, and finally was released in mid-season, apparently at his own request.14

At the age of 23, McGinnity’s baseball career seemed to be over. He and Mary Redpath, a McAlester girl whom he had married the previous fall, moved back to Illinois. He spent the next three years there, doing a little mining, working as a bartender, and playing as much baseball as he could for amateur and semipro teams in the Springfield/Decatur area.

He had always been a conventional power pitcher, throwing straight overhand with a good fastball and an adequate breaking pitch, but during those years back in Illinois he began working on something new. With Kansas City, he had seen a pitcher for the rival Grand Rapids team, Billy “Bunker” Rhines, baffle hitters with an unusual underarm throwing motion. He went to work trying to copy the motion and developed his rising curveball, “Old Sal.” He used the same grip as when he threw overhand but he swept his arm downward and released the ball from somewhere around his knees. It allowed him to throw one breaking pitch after another with less snap in his wrist, reducing the wear and tear on his arm.

“The damn pitch never came straight at you,” baseball historian Robert Smith wrote. “It started near Joe’s shoes, for his fingers almost scraped the ground as he completed the pitch. And it appeared to be approaching crossways and upward, looking big enough to be broken in two, but always just escaping the full weight of the bat.”15

Old Sal revived McGinnity’s professional career. He signed to pitch for Peoria in the Western Association in 1898. After compiling a 9-5 record, including a 21-inning, complete-game victory over St. Joseph, he signed to pitch for the Baltimore Orioles of the National League in 1899.

With Baltimore, McGinnity joined one of the most raucous and aggressive teams in the history of baseball. He immediately became the ace of the Orioles’ staff, pitching 366 innings and winning 28 games. Perhaps more significantly, he made two new friends – a diminutive, scrappy, do-anything-to-win third baseman named John McGraw and a jovial, rotund catcher named Wilbert Robinson. Both became lifelong pals and all three men eventually ended up in the Baseball Hall of Fame.

It was Robinson who first recognized McGinnity’s potential and encouraged McGraw to make him the team’s top pitcher. McGinnity often credited the man everyone called Uncle Robbie with polishing off some of his rough edges and teaching him some new tricks.16

Prior to the 1900 season, the National League condensed from 12 teams to eight. Baltimore and Brooklyn, which had been owned by the same syndicate, were merged into one team. So, McGinnity suddenly found himself pitching for the Brooklyn Superbas (later the Dodgers) that season.

He had spent the offseason working in a new profession, helping his father-in-law in an iron foundry back in McAlester. When Brooklyn Eagle sportswriter Abe Yager interviewed him prior to the new season, McGinnity told him “I’m an iron man.”17 It became his new nickname, although it eventually became more appropriate for other reasons.

He went 28-8 for Brooklyn as the Superbas won the NL pennant by 4½ games over Pittsburgh, but the Pirates weren’t convinced that Brooklyn had the better team. The Pittsburgh Chronicle-Telegraph proposed a special postseason best-of-five series between the two teams, with the winners receiving a special 18-pound silver punch bowl as the prize.

All the games were played at Pittsburgh’s Exposition Park, but Brooklyn had no trouble backing up what it had done in the regular season. It won the series in four games with McGinnity recording complete-game victories in the first and last games. When it was over, his teammates had the silver punch bowl engraved and presented it to him. He kept it for 20 years before giving it to the A.E. Staley Company of Decatur, which many years later gave it to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In 1901, McGinnity found himself with yet another new team. McGraw and Robinson had jumped to the new American League and were heading up a new Baltimore Orioles team there. They convinced Iron Man to join them, signing him for $2,800 a season even though Brooklyn had offered him $5,000 to stay in the NL.

He went 26-20 for the Orioles in 1901 and led the new league in games pitched (48), complete games (39), and innings pitched (382). He also set a modern-era AL record by allowing 412 hits.

McGinnity was 13-10 for Baltimore in the middle of the 1902 season when he was on the move again. McGraw was constantly feuding with American League founder and president Ban Johnson. In the middle of the season, McGraw gained his release and jumped to the New York Giants, maneuvering to take McGinnity and some of his other top players with him.

It was the start of something special. McGinnity went only 8-8 in the remainder of that season – but over the next four years he posted records of 31-20, 35-8, 21-15, and 27-12 with the Giants, teaming with Christy Mathewson to form arguably the greatest 1-2 pitching tandem in the history of the sport. There have been only two instances in which two pitchers on the same team won 30 games in a season. Both times, it was McGinnity and Mathewson.

McGinnity deserves at least some credit for helping the younger Mathewson develop into one of the greatest pitchers who ever lived. Before McGraw and McGinnity arrived, the previous Giants management had been trying to convert Mathewson into a first baseman. McGinnity taught him how to throw a sinker, showed him how he scouted opposing hitters, and gave him tips on fielding the pitching position. Mathewson also observed how McGinnity paced himself and made sure he had something left for tight spots.18

The Giants won NL pennants in 1904 and 1905, but it is the 1903 season for which McGinnity is most remembered. He started 48 games and worked 434 innings — both modern-day NL records — and in August became a veritable one-man pitching staff. On August 1 against the Boston Braves, he pitched and won both games of a doubleheader, 4-1 and 5-2, allowing just six hits in each game. He did it again a week later against Brooklyn and finished out the month on August 31 by again pitching and winning two games in the same day against Philadelphia.

McGinnity modestly insisted there was “never any great trick” to winning both ends of a twin bill. “I was pitching those games with my head, more than with my arm,” he said. “An arm may not be able to go 18 innings in a day unaided, but it’s different with the brain. A slow ball and a few good curves — that was all I had. But I guess it was enough.”19

The Giants came up 6½ games short of winning the pennant that season even though McGinnity and Mathewson each won 30 or more games, but in 1904 they really began dominating the NL. McGinnity won 35 and Mathewson won 33, with Dummy Taylor adding another 21 wins for a team that clinched the NL pennant with 16 games remaining in the season.

It was the best year of McGinnity’s career. Not only did he have a win total that only has been exceeded four times in baseball’s modern era, he also led the National League with five saves (although that statistic was not yet kept). He opened the season with a 14-game winning streak and ended it by winning 12 of his last 13 games. Along the way, there were nine shutouts and 38 complete games. His final earned-run average was 1.61.

The World Series had been established the previous year with Pittsburgh playing the Boston Americans. However, McGraw and Giants owner John T. Brush were still at odds with Ban Johnson, and they refused to play Boston in a postseason series.

But in 1905, after winning another pennant, the Giants finally agreed to play the Philadelphia Athletics in the World Series. They won it in five games, and Mathewson was the hero, hurling shutouts in Games One, Three, and Five. McGinnity was a tough-luck loser in Game Two and the winner in Game Four. Philadelphia did not score an earned run in any of the five games.

McGinnity won 27 games in 1906 and was 18-18 in 1907, but it was apparent that his skills were beginning to decline. He was only a part-time starter while going 11-7 in 1908, although he was involved in one last classic moment when the Giants played the Cubs in an important game late in the season.

The Giants appeared to have won the game on September 23 on Al Bridwell’s single in the ninth inning. But rookie Fred Merkle, who was on first base at the time, did not go all the way to second base, veering off to run to the Giants’ clubhouse as fans rushed the field. As Cubs second baseman Johnny Evers tried to get his outfielders to throw him the ball for a force-out at second that would negate the run, McGinnity, who was coaching third base for the Giants, intervened. There are dozens of conflicting accounts of what actually happened, but all of them have McGinnity wrestling with various Cubs players to get possession of the ball and trying to throw it into the left-field seats. In the end, Merkle was called out and the game was ruled a tie. When the Cubs and Giants ended up tied for the pennant, they had to play a special playoff game at the Polo Grounds. The Cubs won and the infamous incident became known as the “Merkle Boner.”

The playoff game was McGinnity’s last as a major-league player. He gained his release from the Giants the following February and embarked on what would be a long and meandering voyage through the minor leagues as a player, manager, and owner.

He and childhood friend H. Clay Smith started by purchasing the Newark team in the Eastern League. McGinnity took on the unlikely dual role of team president and star pitcher. He pitched more than 400 innings for Newark in both 1909 and 1910, winning 59 games in the two seasons combined. He did not pitch as well in 1911 and 1912, however, and the team began to flounder financially as well.20

Over the next six years, he owned and pitched for a string of teams in the Pacific Northwest in Tacoma, Butte, Great Falls, and Vancouver. He pitched well at times but his franchises almost always ended up falling on hard times financially, prompting another move. The Montana Standard newspaper in Butte noted in an editorial at the time of his death that “as a business man, McGinnity was a mighty good pitcher.”21

After all those years of moving around the country, McGinnity welcomed an offer in 1919 from the A.E. Staley Company back in Decatur. The Staley Fellowship Club was beginning to form sports teams to be affiliated with its massive corn starch manufacturing operation; it hired McGinnity to head up its baseball team. It also brought in a young University of Illinois alumnus named George Halas to play the outfield for McGinnity’s baseball team while also forming a football team. Within a few years, the football team originally known as the Decatur Staleys evolved into the Chicago Bears.

McGinnity, as always, just couldn’t stay in one place for too long. He eventually was lured back into minor-league baseball by a team in Danville, Illinois. He was in his 50s by then but he wasn’t content just to manage his team from the dugout. He still felt the urge to pitch and although he admitted his legs sometimes felt a bit wobbly, he thought his arm was as lively as ever.

“I don’t feel old. Of course not,” he said in one interview. “The idea seems absurd to me. I am able to take my regular turn on the mound and I expect to do that for many years yet. Baseball is too fine a game to give up, ever.”22

He enjoyed one last glorious season as the player-manager with Dubuque in 1923, going 15-12 as a pitcher while managing the team to the Mississippi Valley League championship. After years of being criticized for his overbearing managerial style, in which he often fined players for the smallest indiscretions, he finally was vindicated with a pennant.

“Joe McGinnity was a leader,” the Dubuque Telegraph Herald reported several years later. “He knew inside baseball and he was tricky. He never asked of his fellow players anything he couldn’t do himself. That is the reason why he pulled over a pennant in 1923 with a club that hardly could be rated as the best all-around club in the league.”23

It was his last hurrah. He threw his last pitch at the age of 54 with Springfield in the Three-I League in 1925.

His old friend, Wilbert Robinson, had become manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers and in 1926 he persuaded McGinnity to work with the team’s pitchers. He didn’t last even one full season in the job, though; Mary McGinnity died that June and Iron Man left the team. He spent the next few years living with his only daughter, Marguerite, in Brooklyn. Their small house was just a short walk from Ebbets Field.

McGinnity was diagnosed with bladder cancer in 1929 and underwent surgery in August for the removal of a tumor. As he was entering the operating room, he joked, “Well, I guess it’s the ninth inning for me and I guess they’re going to get me out.”24 Over the next few months, there were frequent reports that he was near death. He finally passed away on November 14 at the age of 58 and was buried alongside Mary at Oak Hill Cemetery in McAlester.

Not surprisingly, tributes flooded in from all over the country, from all the various communities in which he had lived for brief periods of time.

Perhaps the highest compliment came from Dick Kinsella, an old Springfield friend who served as a scout for the Giants. He said he thought McGinnity was the smartest pitcher in baseball history.

“He was what you might call a natural born baseball pitcher,” Kinsella told the Decatur Review. “Although Christy Mathewson was a wonder, I think Joe McGinnity knew more about baseball than Mathewson.”25

An earlier version of Joe McGinnity’s biography appeared in SABR’s “Deadball Stars of the National League” (Brassey’s, 2004), edited by Tom Simon.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and fact-checked by Alan Cohen. It was adapted from the author’s book, Iron Man McGinnity (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 2009).

Notes

1 United Press, “McGinnity’s Novel Theory on Durability of Pitchers’ Arms,” May 5, 1926.

2 Walter Trumbull, “The Listening Post,” Richmond Times Dispatch, November 16, 1929: 11.

3 Some sources give McGinnity’s HBP record as 41. Statistics in this article come from baseball-reference.com and contemporary sources.

4 Ed Burkholder, “McGinnity Was A Man of Iron,” Sport, April 1954: 54

5 Connie Mack, My 66 Years in the Big Leagues (Philadelphia: Winston, 1950), 86.

6 “How M’Ginnity Tabbed His Batters,” Butte (Montana) Miner, May 15, 1916.

7 M.J. Sullivan, “The Men on Whom the Championships Depend,” Pearson’s Magazine, April 1905.

8 Don Doxsie, Iron Man McGinnity (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland Publishing, 2009), 61, 93-94.

9 Dubuque (Iowa) Telegraph Herald, November 14, 1929.

10 “Joe M’Ginnity, Ball Player,” Daily Illinois State Journal, November 15, 1929: 6.

11 Hugh A. Jennings, “McGinnity Greatest Fielding Pitcher in Game, Says Jennings,” Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, December 18, 1925: 38.

12 Doxsie, 5.

13 Ibid., 7.

14 Ibid., 31.

15 Benton Stark, The Year They Called Off the World Series (Garden City Park, New York: Avery Publishing, 1991), 83.

16 Doxsie, 44, 58.

17 “‘Iron Man’ Joe McGinnity,” Dubuque (Iowa) Telegraph Herald, July 23, 1922.

18 Doxsie, 66.

19 James J. Corbett, “‘Ol’ Joe McGinnity, 50, Still Pitching Victories,” Philadelphia North American, July 30, 1922.

20 Doxsie, 117-119.

21 “Iron Man Passes,” Montana Standard, November 18, 1929.

22 Wilton Floberg, “On the Upper Side of Fifty,” Sporting Life, August 1923: 9.

23 Dubuque (Iowa) Telegraph Herald, November 14, 1929. Associated Press, “Joe McGinnity’s Condition Critical After Operation,” Dubuque Telegraph Herald, August 27, 1929.

24 Associated Press, “Joe McGinnity’s Condition Critical After Operation,” Dubuque Telegraph Herald, August 27, 1929.

25 Howard V. Millard, “Joe McGinnity To Rest Beside Wife In Oklahoma,” Decatur (Illinois) Review, November 15, 1929.

Full Name

Joseph Jerome McGinnity

Born

March 20, 1871 at Cornwall, IL (USA)

Died

November 14, 1929 at Brooklyn, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.