Joe Nuxhall

One of baseball’s charms is its lack of timekeeping. Though in most games it can be enjoyable, this charm is a potential source of frustration if a team is losing badly and (since there is no “mercy rule” in the majors) might rather run out a clock than go the full nine innings.

One of baseball’s charms is its lack of timekeeping. Though in most games it can be enjoyable, this charm is a potential source of frustration if a team is losing badly and (since there is no “mercy rule” in the majors) might rather run out a clock than go the full nine innings.

One such game came on June 10, 1944, when Joe Nuxhall became the youngest man ever to play in the major leagues — a mark he still holds.1 The Cincinnati Reds were trailing the St. Louis Cardinals 13-0 in the top of the ninth inning when Reds manager Bill McKechnie called upon 15-year-old Nuxhall to take the mound.

The youngster walked five men and gave up two hits, allowing five earned runs in two-thirds of an inning. True, he was facing a first-rate lineup. The Cardinals finished the year with 105 wins and a World Series victory. Yet why was Nuxhall — who wasn’t even old enough to drive — in what he later described as “a very scary situation”?2

World War II was in full force — D-Day had come just four days before. Professional baseball had lost many able-bodied men to the service, including greats such as Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio. Teams were resorting to extreme measures to fill their rosters. The Reds got clearance under the child labor laws to sign Nuxhall to a contract. “Probably two weeks prior to that, I was pitching against seventh-, eighth- and ninth-graders, kids 13 and 14 years old,” Nuxhall said. “All of the sudden, I look up and there’s Stan Musial and the likes.”3

Nuxhall was so anxious that he tripped on the top step of the dugout on his way out to the mound. Controlling his emotions the best that a 15-year-old could, he was actually able to retire two of the first three batters he faced, walking the second. “I almost drowned. . . suddenly it dawned on me where I was,” he explained years later. “I started to shake all over.” He gave up a walk, which included a wild pitch, and then a single to future Hall of Famer Musial. Three more walks and a single by All-Star second baseman Emil Verban followed. “Then McKechnie came out to lead me away.”4

Nuxhall’s career might have ended after that one outing, with a 67.50 ERA, similar to what happened with Joe Cleary in 1945. Yet “Nuxy” made it back to the majors, although not until 1952, and he stuck around through 1966, long enough to earn another nickname, “The Ol’ Lefthander.” He then went on to a long career as one of Cincinnati’s most beloved broadcasters.

Joseph Henry Nuxhall was born on July 30, 1928 in Hamilton, Ohio, about 20 miles north of Cincinnati. He was the eldest of Orville “Ox” and Naomi (Gailey) Nuxhall’s five children. Two younger brothers, Bob and Don, also went on to play in the minor leagues in the 1950s.

Joe Nuxhall was originally scouted by the Reds at age 14, while pitching in a Sunday baseball league. His father played in that league too, and initially it was Ox whom the scouts were interested in signing, even though he would have been quite old in baseball terms. However, the elder Nuxhall didn’t want to play pro ball. He was focused on raising his children and didn’t want to jeopardize his stable job at a local General Motors plant, Fisher Body.

Instead, attention turned to Joe. “The way I tell it is I beat my father out of a job,” Nuxhall joked.5 Already standing 6-foot-2 (he later grew another inch), Joe was the largest in his ninth grade class. He had an 85-mph fastball, albeit wild. On February 18, 1944 Nuxhall signed his first professional contract with the Reds, worth $175 per month; he got a $500 signing bonus.6 Still a kid living at home with his parents, he bought them a new carpet with his newly-gained baseball earnings.

He signed in February, but Nuxhall had to wait until school let out in June before reporting to the Reds, though his school principal allowed him to be in uniform at Crosley Field for Opening Day. In April 1944, The Sporting News wrote: “It’s a wise manager who knows his own roster these days, due to the rapid changes in draft status and inductions. Original rosters, issued before the start of spring training, quickly lost most of their significance –and it is likely that a high rate of turnover, especially of the athletes under 27 years of age, will continue as the season progresses.”7 Nuxhall was deemed suitable for the Reds’ roster because he was under-age for the draft and also a local prospect.

After his rocky June 10 debut, Nuxhall was assigned to the Birmingham Barons of the Southern Association (Class A1). He pitched only one more inning that summer, and it was a similar experience. He walked five and allowed six earned runs.

The following season, the 16-year-old Nuxhall improved considerably. He posted a 3.21 ERA over 23 games, pitching for both the Syracuse Chiefs (Class AA) and Lima Reds (Class D). Despite his young age, he struck out an impressive 41 batters in his first 27 innings at Lima.

After the 1945 season, Nuxhall voluntarily retired from baseball and returned to Hamilton High School for his diploma. Under high school athletic rules he was still considered an amateur in sports other than baseball. He was a well-rounded athlete, earning all-state honors in football and basketball as a senior in 1946.

Nuxhall also returned to professional baseball in 1947, playing in the Reds farm system. He married Donzetta Thomas on October 4, 1947 and the couple had two sons, Phil and Kim. Like his father and uncles, Kim played pro baseball. He was in the low minors for the Reds from 1972 through 1974.

Nuxhall developed as a pitcher in the Reds chain through 1951, spending time with the Muncie Reds, Tulsa Oilers, Columbia Reds, and Charleston Senators. Playing long before the designated hitter rule went into effect, Nuxhall also gained notice as a fairly talented batter. He clubbed 15 career home runs in the majors with a .198 lifetime batting average.

Nuxhall returned to Cincinnati’s major-league roster in 1952. Gabe Paul had taken over as Reds general manager the previous off-season and made many personnel changes. Only 15 players from the 1951 campaign were on Cincinnati’s roster of 34 men during spring training in 1952.8 With “dazzling pitching” and improved control, the 24-year-old Nuxhall impressed management enough to make the major-league roster.9 On May 21, he made his first appearance in a big-league game since he was a boy, pitching three innings of relief, allowing no runs and striking out three batters. A little over a month later, he picked up his first major-league win against the New York Giants. Mostly pitching out of the bullpen, he finished the 1952 season with a 1-4 record and a respectable 3.22 ERA over 37 games.

Between 1952 and 1960, Nuxhall remained a fairly consistent relief and starting pitcher. Manager Birdie Tebbetts said, “Joe has a good chance to become one of the outstanding pitchers in the National League. He’s a great competitor and hits and fields capably enough to help himself gain stature as a successful pitcher.”10 In 1954, 10 years after he signed his first contract, he became a major-league winner, posting a 12-5 record.

Nuxhall’s three best consecutive seasons were arguably 1954 through 1956. During that stretch, he accrued a 42-28 record and 3.66 ERA with an average of 208 innings pitched per season. He was named an All-Star in 1955 and 1956 and led the National League leader in shutouts in 1955 with five. All-Star Dick Sisler said, “That kid’s got it in spades. He’s as quick as Curt Simmons, whom I rated the most overpowering pitcher in the league before the Phillies lost him to the service. Nuxhall also throws quite a curve; in fact, it’s the type which fairly explodes.”11 Nuxhall annually set a personal goal to win at least 15 games, achieving it with 17 in 1955.

Nuxhall began to slide in 1957. From then through 1960, he had a record of 32-38 with a 4.29 ERA. Still fairly young, his struggles were more mental than physical. His temper was notorious; it took him out of games through both score and ejections. “One pitch loses me a game, gets me thrown out, I’m fined by the league, and lectured by Birdie,” Nuxhall said. “And I kick the sandbox (for cigarette butts) in the clubhouse so hard I almost break my toe.”12

After Tebbetts took him out of another game, he tore up his glove, finger by finger, while walking back to the dugout.13 He also once charged an umpire, nearly knocking him down, and was later fined $250 and suspended five games. Highly competitive by nature, Nuxhall explained his temper: “I never got mad at someone making an error behind me. I got mad at myself, or at an umpire’s decision. I just hate to lose.”14 It would be several more years until he was able to channel his emotions productively.

Making things worse, he was increasingly unpopular when pitching at home in Cincinnati. Culminating in 1960, seemingly every time Nuxhall took the mound, he heard nothing but boos and catcalls. “I’m as stout-hearted as anyone,” he said, “but when you keep hearing them, it’s going to get to you. Anyone who says it doesn’t is just kidding himself.”15

Nuxhall requested a trade after the 1960 season; he was subsequently dealt to the Kansas City Athletics in exchange for John Briggs and John Tsitouris. Despite the trade, he continued to struggle on the mound, going 5-8, 5.34 in 37 games. Yet he also took pride in two home runs that year. One came against friend and former teammate Art Fowler; the other was off Hall of Famer Whitey Ford.

The A’s released Nuxhall after the 1961 season, and he then signed with the Baltimore Orioles. Just before Opening Day in 1962, the Los Angeles Angels purchased his contract from Baltimore, but in five games he was ineffective. The Angels released him in mid-May.

By then 33 years old, many men with less competitive spirit probably would have retired. Instead, Nuxhall signed a minor-league contract with the San Diego Padres, then a Reds farm team. Early in his career, Nuxhall was told, “master your temper and you’ll master your pitches.”16 Yet it wasn’t until he arrived in San Diego that he was able to put this advice into practice. “Going to San Diego was the best thing that ever happened to me,” he later said. “I regained my confidence and learned to control my temper. Before I went there, I was scared to throw a fastball inside to a right-handed hitter… In San Diego it hit me. I realized I had never won a game by getting mad.”17 He added, “I still get mad. I just don’t let it take over my thought and pitching anymore.”18

Harnessing his temper, he quit trying to overpower every hitter. He also shortened his windup and began to pitch to spots, saying, “I found I had my eye constantly on target for the first time in my life.”19 After these major adjustments, he achieved a 9-2 record in San Diego and earned a midseason promotion.

Nuxhall returned to Cincinnati a changed man and pitcher, and he endeared himself to his home region’s crowd. The same fans that had once booed him began to cheer instead. It was then that he earned the nickname that stayed with him for the rest of his career, “the Ol’ Lefthander.” He finished the 1962 season with a 5-0 record and 2.45 ERA for the Reds. “Sounds funny,” Frank Robinson said, “but at his age Joe’s learning to pitch.”20

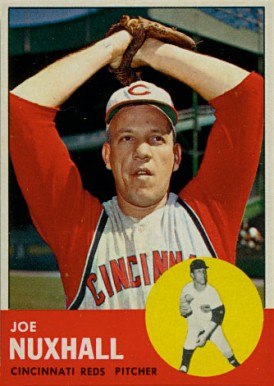

At age 34, Nuxhall’s success carried over into the 1963 season. Starting 29 games in 35 appearances, he finished with a 15-8 record and 2.61 ERA, accomplishing his personal goal of winning 15 games in a season for the second time in his career. Nuxhall was named Comeback Player of the Year by the Cincinnati Chapter of Baseball Writers of America in 1963.

Nuxhall pitched three more moderately effective seasons for the Reds as a swingman. “I used to be a good hitter,” he said modestly in 1964. “But I’m not anymore. I even was used as a pinch-hitter on occasions.”21 When asked that year about his plans for after his playing career ended, he replied he was “not prepared to do anything” outside the sports field and that he would like to be a baseball coach, but not if it took him away from his home in Hamilton.22

Nuxhall officially retired as a player in April 1967. Over the course of his career, he amassed a record of 135-117 and a 3.90 ERA. Nuxhall earned 130 of his wins in Cincinnati and held the club record for career games pitched from 1965-1975. He still holds the record for left-handers. Nuxhall was inducted into the Reds Hall of Fame in 1968, less than a year after his playing career had ended.

Immediately following his retirement, Nuxhall remained in the Reds organization, embarking on his second career as a member of the broadcast team. Despite his lack of experience behind the mike, the knowledge Nuxy had gained during his long playing career served him well as a broadcaster and impressed his colleagues in the media. “I think it’s wonderful the way ex-pitchers like Waite Hoyt and Nuxhall can translate a pitch on radio in terms of their own experience,” Cincinnati Post sports editor Pat Harmon wrote in 1969. “I’m doubly impressed when a guy like Nuxhall tells me the pitcher just threw a certain kind of pitch and where it crossed the plate.”23 Nuxhall became accomplished in his new field. Several times he was a finalist for the Ford C. Frick Award, first in 2007.

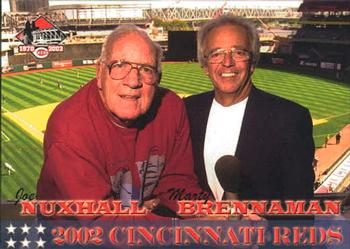

Nuxhall partnered with Jim McIntyre and Al Michaels; then, beginning in 1974, he worked alongside Hall of Fame and Frick Award winner Marty Brennaman. Nuxhall and Brennaman first met on February 1, 1974 in Dayton, Ohio at a photography studio where their publicity shots were taken. “The first thing I said to him upon shaking his hand was, ‘I have your baseball card,’” said Brennaman. “From that day forward, it was a relationship in our profession that people only dream about.”24

The two broadcast together for 31 seasons, becoming known to their audience simply as “Marty and Joe.” Brennaman did mostly play-by-play and Nuxhall provided color commentary. Although he’d endeared himself to Reds fans as a player, Nuxhall did so in a different way with his radio style. Whereas Brennaman could be cantankerous at times, Nuxhall was a perfect foil, describing games in a slow-paced, down-home manner that caught on with listeners.25

The two broadcast together for 31 seasons, becoming known to their audience simply as “Marty and Joe.” Brennaman did mostly play-by-play and Nuxhall provided color commentary. Although he’d endeared himself to Reds fans as a player, Nuxhall did so in a different way with his radio style. Whereas Brennaman could be cantankerous at times, Nuxhall was a perfect foil, describing games in a slow-paced, down-home manner that caught on with listeners.25

Yet Nuxhall still also brought the same passion and enthusiasm he had as a player to the booth, getting emotionally invested in the games. “While Brennaman describes the flight of the ball, Nuxhall’s plaintive voice in the background is screaming, ‘get up, get up… get out of here,’” Hall of Fame reporter Hal McCoy wrote of Reds broadcasts. “I know it sounds terrible, but that’s what I’d do if I was sitting in the dugout, it’s the way I react to things,” Nuxhall said.26 He added, “It’s like being a player. If you don’t have enthusiasm on the field, you’ve lost your competitive spirit. The same holds true in the booth.”27

The Ol’ Lefthander never quite left the field; he was known to pitch batting practice before games. Being a radio broadcaster also allowed him to be part of events he didn’t get to as a player. “In all my days as a player, I never played for a winner,” he said. “Being with the Reds as a broadcaster is the next best thing.”28 With Brennaman at his side, he called the Reds games as they won the World Series in the 1975, 1976, and 1990 seasons.

Nuxhall did pregame interviews with players, known as the Turfside Show, in addition to postgame player interviews, where he developed his signature radio signoff phrase “This is the Ol’ Lefthander, rounding third and heading for home.” This phrase is displayed on the outside of the Reds’ stadium, Great American Ball Park.

Nuxhall lived in Fairfield, Ohio and was known to frequent many of the area’s Bob Evans restaurants. Despite battling prostate cancer in 1992 and suffering a mild heart attack in 2001, he remained a fixture in the Reds radio booth until 2004. Over 60 years after his professional debut, Joe Nuxhall officially retired as a full-time broadcaster. Nuxhall was honored in an on-field ceremony prior to a game on September 18, 2004. More than 40,000 fans cheered and greeted him with a standing ovation as he took the field. “Joe is a person that gives you a feeling of what this game’s really about,” said Hall of Fame manager Sparky Anderson. “Six decades — imagine that. And he’s never changed. I’m so proud of him, he’s the same old guy. If he doesn’t go into the Hall of Fame, we’re not doing a very good job. He’s one of the genuinely likeable guys in baseball.”29

Nuxhall remained active, especially with activities and charities that benefited his home community. Beginning in 1985, he raised money for the Joe Nuxhall Memorial Scholarship through an annual golf outing. In 2003, he raised additional funds for the Joe Nuxhall Character Education Fund, which supports workshops and grants for teachers, coaches, and others who work with children. In September 2004, the book Joe: Rounding Third & Heading for Home was written about him; a portion of the proceeds benefited the character education fund. “It’s rewarding, and it’s nice to be a part of it,” Nuxhall said.30 For his efforts, August 18, 2006 was declared “Joe Nuxhall Day” in the state of Ohio.

Unfortunately, Nuxhall was diagnosed in 2003 with lymphoma, an illness that this fiery competitor fought until the end. Joe Nuxhall died on November 15, 2007 in Fairfield at the age of 79.

With over six decades of involvement, Nuxhall affected generations of Reds and baseball fans alike. “This is a sad day for everyone in the Reds organization,” Reds right fielder Ken Griffey Jr. said in a statement. “I’m in shock. I’ve known Joe my entire life. He did so many great things for so many people. You never heard anyone ever say a bad word about him. We’re all going to miss him.”31 The following Opening Day game, the Reds honored Nuxhall by wearing jerseys with his number, 41. They also wore sleeve patches with the word “NUXY” for the remainder of the 2008 season. “I got to know Nuxie since I’ve been here in ’03,” Reds pitcher Bronson Arroyo said. “That’s one of the better guys you’re going to find around here. If you don’t know anything about the Reds, he’s a legacy around here.”32

Joe Nuxhall was remembered by many as humble, understanding, and compassionate, and his legacy endures. His likeness was cast in bronze, and since 2003 it has stood at the entrance to Cincinnati’s Great American Ball Park. Hamilton County and the city of Cincinnati also honored him by changing the street running next to the stadium Joe Nuxhall Way. The cities of Hamilton and Fairfield also named a street in his honor.

In keeping with the giving spirit of Joe Nuxhall, his son Kim oversaw his father’s dream of a baseball league for disabled children. Opened in 2012, The Joe Nuxhall Miracle League has broken down barriers to allow everyone to play the game about which Nuxhall was so passionate.

Marty Brennaman put it simply in 2003. “I have no reluctance in saying this: There’s been more popular players. But there is not a more popular figure in the history of this great franchise.”33

- Related links: Listen to our SABR Oral History Collection interviews with Joe Nuxhall, conducted by Kit Crissey in 1972 and by Walter Langford in 1985.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

For this biography, the author relied primarily on a sizeable stack of clippings from Nuxhall’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York. Baseball-Reference.com was also helpful in completing this biography.

Notes

1 Since World War II ended, two players have made their big-league debuts at the age of 16: Alex George (1955) and Jim Derrington (1956).

2 Associated Press. “Reds broadcaster Nuxhall dies,” Fox Sports on MSN, November 19, 2007.

3 Ibid.

4 Les Biederman, “Nuxhall, Released By Angels, Started With Reds When 15,” Pittsburgh Press, May 13, 1962.

5 Red Smith, “Schoolboy Joe Looks Back,” New York Times, April 11, 1976.

6 Biederman.

7 “Starting Rosters, With Positions — From Uncle Sam’s Scorecard,” The Sporting News, April 13, 1944.

8 Tom Swope, “Newcomers Give Shine to Rhinelanders’ Outlook,” The Sporting News, March 18, 1952.

9 Tom Swope, “Nuxhall Improves Control While Controlling Temper,” The Sporting News, March 18, 1952.

10 Tom Swope, “Nuxhall Tops Red Staff in Years and Victories,” Cincinnati Post, February 1, 1955.

11 Lou Smith, “Chief Praise Goes To Nuxhall After Stint Against Veteran Batters,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 4, 1952.

12 Si Burick, “Schoolbody Joe to Hamilton Joe; Now It’s Hall of Fame Joe,” Dayton Daily News, July 12, 1968.

13 Si Burick, “Nuxhall Could Write a Book About Past ‘Bad Boy’ Antics,” Dayton Daily News, July 1, 1963.

14 Libby Lackman, “Joe Nuxhall Fought Back At His Temper And Pitched The Boos Away,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 11, 1964.

15 Earl Lawson, “Downhearted Nuxhall Flaps Crying Towel,” The Sporting News, January 4, 1961.

16 Earl Lawson, “Gritty Nuxhall Dragged Himself Off Junkpile, Leaped to Summit,” Cincinnati Post, November 2, 1963.

17 Pat Harmon, “Nuxhall Youngest, Could Be Oldest,” Cincinnati Post & Times-Star, July 19, 1965.

18 Lackman.

19 Si Burick, “Nuxhall Could Write a Book About Past ‘Bad Boy’ Antics.”

20 Sandy Grady, “Joe Nuxhall Calls Hurling Child’s Play,” Philadelphia Bulletin, May 11, 1964.

21 Arthur Daley, “The Boy Grew Older,” New York Times, May 10, 1964.

22 Lackman.

23 Pat Harmon, “Nuxhall Calls It A Spitball,” Cincinnati Post, September 11, 1969.

24 Mark Shelton, “Brennaman looks back on Nuxhall,” MLB.com, November 16, 2007.

25 “Remembering Hamilton Joe Nuxhall: One of Baseball’s Good Guys,” Hubpages.com, September 11, 2014.

26 Mark Shelton, “Brennaman looks back on Nuxhall.”

27 Hal McCoy, “Fun and enthusiasm trademarks of Marty and Joe,” Cincinnati Reds Scorebook, 1978.

28 Ibid.

29 Todd Lorenz, “Reds honor Nuxhall in ceremony,” MLB.com, September 18, 2004.

30 Pete Conrad, “Nuxhall’s new dream to raise money for $7.5 million children’s center,” Dayton Daily News, March 2007.

31 Mark Shelton, “Nuxhall leaves behind many friends,” MLB.com, November 16, 2007.

32 Ryan Ernst, “Reds honored to wear Nuxie’s number,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 3, 2008.

33 John Fay, “Old Left-hander is cast in bronze,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 21, 2003.

Full Name

Joseph Henry Nuxhall

Born

July 30, 1928 at Hamilton, OH (USA)

Died

November 15, 2007 at Fairfield, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.