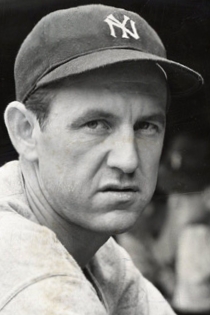

Lefty Gomez

Lefty Gomez made a lasting mark on baseball for two reasons. Not only was he one of the two or three finest pitchers of his generation, but he was probably the wittiest person ever to wear a major league uniform. In a 14-year big league career spanning 1930-43, all but one game of which was spent with the New York Yankees, he won 189 games against only 101 losses for a .649 winning percentage. He won 20 or more games four times and held opponents to a lifetime .242 batting average while pitching in the heavy-hitting 1930’s. He was particularly effective in the World Series, winning six games in the Fall Classic without a loss.

Lefty Gomez made a lasting mark on baseball for two reasons. Not only was he one of the two or three finest pitchers of his generation, but he was probably the wittiest person ever to wear a major league uniform. In a 14-year big league career spanning 1930-43, all but one game of which was spent with the New York Yankees, he won 189 games against only 101 losses for a .649 winning percentage. He won 20 or more games four times and held opponents to a lifetime .242 batting average while pitching in the heavy-hitting 1930’s. He was particularly effective in the World Series, winning six games in the Fall Classic without a loss.

Through it all he was quick with a quip, for example, attributing his success to “clean living and a fast outfield.” Once after an inning in which three hard hit balls were run down and caught by his outfielders, he said, “I’d rather be lucky than good.” After he finally retired from baseball he was called upon to fill out a job application form. In the “reason for leaving last employment” blank, Lefty wrote, “Couldn’t get anybody out.” He even added to the permanent language of baseball, originating the term “gopher ball.” It happened during his rookie year in 1930 when Gomez was explaining after an outing in which he had given up several home runs, that his outfielders were required to “go fer” one ball after another.1

Gomez had a screwball personality as well, once placing a call to South Africa because he just wanted to talk to someone, anyone, there. While lobby sitting one day and watching some goldfish swimming in a bowl, he “invented” a revolving goldfish bowl to make life easier for the older goldfish.2 He famously held up a World Series game he was pitching to watch a plane fly overhead.3 As a result, sportswriters soon begin calling him “El Goofy.” With his Castilian and Irish heritage he was also sometimes called “the Gay Caballero” in the press as well as “the singular senor,” “the lanky Castilian,” “the Hibernian-Hildago” and the Castilian-Celt.”4

Gomez was a notoriously weak hitter, batting just .147 for his career, with nary a home run. In one oft-told incident, Lefty was batting against the young but wild flame-throwing Bob Feller late in the second game of a doubleheader at Yankees Stadium. The afternoon shadows were long and when Gomez stepped into the batter’s box, he promptly pulled a cigarette lighter out of his pocket, flicked up a light, and held it in front of his face. The umpire was not pleased and said, “C’mon Lefty, are you trying to make a joke out of the game? You can see Feller just fine.”

The quick-witted Lefty responded, “Hell, I can see him. I just want to make sure that wild man out there can see me.”5

Much of his humor was self-deprecating. An example was when Neil Armstrong first set foot on the moon in 1969, and he and NASA scientists were puzzled by an unidentified white object. Upon hearing of it, Lefty said, “I knew immediately what it was. It was a home run ball hit off me in 1937 by Jimmie Foxx.”6 Fellow Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts heard most of Lefty’s stories and said, “Just once I’d like to hear Lefty tell a story where he got someone out.”7

Vernon Louis “Lefty” Gomez was born on November 26, 1908, the youngest of eight children, at his family’s homestead in Rodeo, California, on the south coast of San Pablo Bay northeast of San Francisco.8 His father was of Spanish-Portuguese descent, grew up a cowboy, and was known as Coyote his entire life. His mother, the former Lizzie Herring, was a sixth generation American of Welsh-Irish descent.9 Coyote managed a 1,000 acre ranch in Franklin Canyon, so Lefty and his brothers rode horses and became hired hands almost as soon as they could walk. Lizzie owned fifteen dairy cows, and as a result Lefty and his siblings would be up at 4:00 am to milk the cows and clean out the stalls before heading to school.10

When he was only six years old Lefty attended the San Francisco World’s Fair and watched famous pilot Lincoln Beachey crash into the bay while attempting a stunt. Not deterred, that day began a love of aviation that lasted the rest of his life.11 When he was eight, Lefty attended a 4th of July parade in Rodeo and began another lifelong love, that of the saxophone. His brother Earl surprised him with his first saxophone on his ninth birthday, prompting Lefty to take a job plucking chickens at a local butchers to raise the $8.00 a month for lessons, which were a five-mile walk up the road.12

Another lifetime passion began when Lefty started playing sandlot baseball for the Rodeo town team when he was only 13. He was such a talent that by age 14 in 1923 he pitched throughout central California from Fresno to Mount Shasta13 and even tried out for the San Francisco Seals in the Pacific Coast League at the end of the season. Nick Williams, the Seals’ chief scout, was impressed with Lefty’s arm but not his 6’2″ 125 pound frame, telling him to come back when he had fattened up.14 The Pacific Coast League played 200 plus game seasons, and Williams simply did not believe skinny pitchers had the stamina to make it through. It was the first of several tryouts with the Seals, with Williams always telling Lefty to come back after he had gained weight.

Gomez obtained a summer job with Union Oil scraping sludge from the stills at the refinery. The manager of the company baseball team would not let Lefty and his fellow workers play on the company baseball team, calling them a bunch of “screwbeanies” because of their menial jobs. Undaunted, they formed their own “Screwbeanies” league and played yard gangs at other oil companies. The team went 15 and 5 to win the Screwbeanies League championship while the Union Oil company team finished in the cellar in its league.15

Lefty attended Richmond High School, a train ride west from Rodeo, because the local high school did not have a baseball team. During his senior year, Gomez was offered a scholarship at St. Mary’s College, a small school five miles east of Oakland. His father was adamant that Lefty should give up baseball, go to college, and become an engineer like his older brother Milfred. Defying his father, in August Lefty secretly pitched for the Point Reyes semi-pro team in Sonoma County. After Lefty lost a 2-1 game against arch-rival Novato in the final game of the 1927 season, Nick Williams of the Seals finally relented and signed the young flame-thrower to a professional contract.16

Coyote reluctantly gave his blessing and signed the contract so that Lefty could report to the Seals’ 1928 spring training. Williams was not convinced that Gomez was ready for the Coast League, however, and quickly farmed him out to the Salt Lake City Bees of the Class C Utah-Idaho League for the season. The Bees were in a cost-cutting mode and decided to keep only three pitchers, one of whom was to be a southpaw. It came down to Lefty and Thornton Lee, who later became a very good pitcher for the Chicago White Sox. The two each pitched a game of a doubleheader and Lefty won the spot when he pitched a shutout in the first game. Lee lost the second game 1 to 0 and was given his walking papers.17

Although the conditions were primitive and the team played on a rock-strewn surface called Community Field, the league had a number of prospects who would make their mark in the game, including Ernie Lombardi, Dolph Camilli, Woody Jensen, Curt Davis, Johnny Vergez, and Ed Coleman. The long season did take its toll on Gomez, who was down to a scant 120 pounds by the dog days of summer. For the year, he finished with 12 wins against 14 losses with a respectable 3.48 earned run average for the pennant-winning Bees. Perhaps more importantly, he led the league with 172 strikeouts in 194 innings.

When Charley Graham, one of the Seals’ owners, came to Salt Lake near the end of the season, Lefty was afraid he was going to be released because he had lost more games than he had won. But Graham told him that Bees’ manager Bob Coltrin said Lefty had ice water in his veins and that he was to report to the Seals’ spring training for 1929.18

Nick Williams was still a skeptic, especially of Lefty’s ability to be a starter. That began to change when the Seals played the Pittsburgh Pirates in an exhibition game that spring. The Pirates lineup was loaded with Paul and Lloyd Waner and Pie Traynor and they blasted the Seals’ starter, who only got a single out in the first inning. Lefty practically inserted himself into the game and proceeded to shut out the Bucs for 8 2/3 innings, giving up only two hits.19

Williams was still not convinced, and Gomez began the season in the bullpen. Lefty, however, was not shy and frequently badgered his manager to let him pitch. In early May, Williams penciled Gomez in as the starter and he promptly pitched a five-hitter. He won his next start as well and was in the rotation for good. At one stretch in the middle of the summer Lefty won 11 in a row, prompting the New York Yankees to fork over $35,000 for his rights. Since the Seals were in the middle of a pennant race, the Yankees agreed to let Gomez finish the season in San Francisco.20 For the year, Lefty compiled an 18-11 won-loss record in 267 innings and led the offense-minded Pacific Coast League with a 3.44 earned run average.

The Yankees neglected, however, to advance Lefty train fare to spring training across the country in St. Petersburg, Florida, so Seals’ teammate Ping Bodie got Gomez an off-season job working as his assistant at Universal Studios in Hollywood. Between that and pitching on Sundays for the Hollywood Hills club in winter league baseball, Gomez saved enough money to get to spring training. First, however, he was ordered by Jacob Ruppert of the Yankees to spend the month of January at a health farm in Saratoga, California to gain weight. It turned out to be the first of three consecutive Yankee-mandated off-season stays there.21

When Gomez finally reported to the Yankees in St. Petersburg in March 1930, he was just 21 years old. He was a full 6 feet 2 ½ inches tall and tipped the scales at 147. He was given an ill-fitting uniform top and told by Manager Bob Shawkey to pitch batting practice. As it happened, the first batter he faced was none other than Babe Ruth. He immediately showed promise with his high leg kick and blazing fastball and soon the great southpaw pitcher Herb Pennock took Lefty under his wing, both on and off the field. Pennock, known as the Squire of Kennett Square (Pa.), rode the hounds and was a sharp dresser. On the downside of a Hall of Fame career, he helped both with Lefty’s pitching mechanics and his wardrobe.22

Gomez’s first big league camp was not without incident. On March 20, in an extra-inning game against the Cardinals, he threw a fastball down the middle and it came back even faster, hitting him in the mouth and necessitating caps on his front teeth. He made the team nonetheless, but again was not in the rotation at the start of the season. Manager Shawkey first summoned Gomez during a Patriot’s Day doubleheader against the Boston Red Sox on April 19 in Fenway Park. Lefty was shaking when he got to the mound, but Shawkey, it turned out, only wanted his glove because Pennock, who was pitching, had broken the webbing on his.23

Lefty’s real first Major League appearance occurred 10 days later in Griffith Stadium against the Washington Senators. He entered the game in the fourth inning of a 7-7 tie and gave up one run in four innings. The Yankees could not score again, so Gomez took the loss in his first big league game. He got his first start a week later, on May 6 against the Chicago White Sox. After giving up a home run to Willie Kamm in the second inning, Gomez pitched shutout ball the rest of the way, scattering five hits, walking none and striking out six to win his first major league game by a score of 4-1.

Five days later, he made his second start against the Detroit Tigers. The game was tied 3-3 heading into the seventh inning, but the Yankees went on a hitting rampage, scoring four runs in the seventh and seven more in the eighth as Lefty coasted to a 14-5 victory. He even had a rare good day at the plate, going 2 for 4 and scoring his first big league run.24

Yankees’ owner Jacob Ruppert and General Manager Ed Barrow remained concerned that Gomez could not top 150 pounds on the scale and were told that Lefty probably had an infection from abscessed teeth in his bloodstream resulting from shoddy dental work when his teeth were capped in spring training after he was nailed by the line drive. The solution, after the Yankees returned from a long road trip in June was simple – pull all of his upper teeth. So at 21, Lefty was soon sporting “ceramic choppers” at a cost to the Yankees of $1,500.

The effects of all that oral surgery and his attempting to adjust to his false teeth really did weaken Lefty and affect his pitching. His earned run average ballooned to over five and he was rarely being used, so in late July the Yankees shipped him out to the St. Paul Saints in the American Association so he could work himself back in shape. He pitched regularly there, compiling an 8-4 won-loss record in 17 appearances and nine starts. Although his ERA in St. Paul was 4.08, his fastball was alive and well as he struck out almost seven batters per nine innings pitched.25

The Yankees finished third in 1930, 16 games out of first place, costing Bob Shawkey his managerial job. Ruppert hired Joe “Marse Joe” McCarthy to take his place and McCarthy, like Shawkey, started the 1931 season with Lefty in the bullpen. He made his first appearance April 20th, pitching 3 2/3 innings of shutout ball against the champion Athletics, striking out five. That performance earned him a start five days later against the Red Sox. Gomez threw seven innings, surrendering three runs while striking out seven and ending with a no-decision.26

After rather indifferent success for the next month, Gomez took the hill on May 26th against the Philadelphia Athletics in Shibe Park. The powerful Athletics were riding a seventeen game winning streak, but Lefty stopped that in its tracks with a complete game 6-2 victory for his first win of the year.27 It was certainly not his last, however, as Gomez began delivering one outstanding performance after another for the Yankees, who finished in second place, 13½ games behind the rampaging Athletics. He topped 20 wins for the first time in his career, finishing with a 21-9 record, and his 2.63 earned run average was second only to Lefty Grove, who won 31 games that year. Lefty gave up only 7.63 hits per nine innings, best in the league and was third in strikeouts with 150.

To say that Gomez quickly embraced all that New York City had to offer would be an understatement. Although his personality never changed, he quickly became a sharp dresser and a lover of the Big Apple’s nightlife, though just a little over a year removed from arriving in St. Petersburg with a cardboard suitcase. On a Sunday night in June 1931, he attended a nightclub show at the Woodmansten Inn in the Bronx with teammates Jimmie Reese and Myril Hoag and immediately became smitten with June O’Dea, a stunning brunette who had just landed a lead role in the Broadway musical You Said It.28

June, born Eilean Frances Schwarz in Boston, was only 18 years old when she met Lefty. According to Lefty, he attended so many shows of You Said It that summer that “I could have acted in it.” It must have had the desired affect because on August 31 the couple returned to the Woodmansten Inn to announce their engagement.29

Shortly after they began dating, June attended her first baseball game in Yankee Stadium to watch Lefty pitch. The game was a tight one, but Gomez blew a one-run lead to the Tigers in the ninth and then gave up two more runs in the 10th to lose 4 to 2. Afterwards, June consoled Lefty, telling him, “Don’t worry, you’ll beat them tomorrow.” She was unaware that starting pitchers pitched only every four days or so.30

Lefty began the 1932 season as an established big league star for the first time and did not disappoint, helping propel the Yankees to win 19 of their first 25 games. The team never looked back, winning 107 games while losing only 47 to win their first pennant since 1928, finishing 13 games ahead of the still powerful Athletics. Lefty finished with a sterling 24-7 record and was fifth in the Most Valuable Player voting, first among pitchers.

One member of the ‘32 Yankees was a rookie pitcher named Charlie Devens, whom the team had signed off the Harvard campus for a hefty bonus. Devens was the scion of a wealthy Boston banking family, and, as a condition of his signing, his father had insisted that his son not be farmed out to Newark but remain with the Yankees for the entire year. As a result, Devens spent the entire year on the Yankees roster although he appeared in only one game.

Late in the season the Yankees had gathered on the platform of the Back Bay Station in Boston, waiting for a train back to New York. Lefty, who knew nothing of Devens’ contract, noticed Devens’ suitcase, a battered but expensive piece of luggage. It bore labels from famous hotels in Cairo, Paris, Rome, and other European cities. “You’ve traveled a lot, haven’t you?” asked Lefty.

“Why, yes, I suppose I have, Mr. Gomez,” answered Devens.

“Tell me,” said Lefty, “have you ever been to Newark?” 31

The Yankees faced the Chicago Cubs in the 1932 World Series and won the first game 12-6. Manager McCarthy gave Gomez the ball for Game 2 so that he could go against the Cubs’ top pitcher, Lon Warneke, who had won 22 games while losing only six. The visiting Cubs scratched across an unearned run in the top of the first inning, but the Yankees responded quickly with two runs in the bottom half of the inning on singles by Lou Gehrig and Bill Dickey. The Cubs tied the score in the third when Babe Ruth misplayed a ball in right but the Yankees added three more runs to secure a 5-2 victory. Lefty went all the way for his first World Series win in what he always said was the greatest thrill of his career.32

The Yankees went on to sweep the Cubs in four straight, with Ruth’s famous Called Shot taking place in Game 3 in Chicago. Lefty was now a full-fledged celebrity. After the Series, he signed on for a $3,000-a-week, 12-week vaudeville run in and around New York where he delivered a ten-minute monologue on life in the big leagues, followed by a three-minute slapstick comedy skit. Although June O’Dea recalled that he had impeccable timing, he quit the gig after five weeks, in part because he didn’t like putting on stage make-up and lipstick.33

Lefty and June finally got married on February 26, 1933 in New York City. June had broken off the engagement at one point because Lefty persisted in wanting her to give up her stage career, which she refused to do. But Lefty realized finally that he was not going to win that argument, and persuaded June to accept the engagement ring again. By the time of their marriage, June was starring with future United States Senator George Murphy in George Gershwin’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play Of Thee I Sing. The day after the wedding, June headed to Philadelphia where Of Thee I Sing was playing and Lefty headed to spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida. The two didn’t see each other for six weeks.34

Gomez and the Yankees began the 1933 season impressively, finishing April in first place. On May 4, Lefty took a no-hitter into the ninth inning in Detroit against the Tigers before giving up a home run to Charlie Gehringer. By the end of June, Gomez stood 9-5 but he slumped for the next two months, going three weeks in August without a win as the Yankees fell behind the upstart Washington Senators. He was plagued by blisters on the tips of his fingers, but tried to pitch through them.35 He pitched well in September, although the Yankees could not catch Washington and finished in second place, seven games out of the lead. For the year, Gomez ended with 16 wins against 10 losses. His 163 strikeouts led the league while his 3.18 earned run average was fourth best.

Lefty was selected for the American League team for the first All-Star game, held that year in conjunction with the Chicago World’s Fair. He even got to see his wife, who was in Chicago touring with Of Thee I Sing.36 Manager Connie Mack chose Gomez to start the game over his own Lefty, Grove. He pitched three shutout innings in an eventual 4- 2 American League victory. Not only was Gomez the winning pitcher in the first All-Star game, he drove in the first run in All-Star history, with a two-out line-drive single to centerfield in the second inning off Wild Bill Hallahan to drive in Jimmy Dykes.37

Lefty quickly put his disappointing 1933 season in his rearview mirror and by the 1934 All-Star break, sported a 14-2 record as the Yankees battled the Tigers for the pennant. His remarkable start resulted in his being the first pitcher ever on the cover of Time magazine.38 It also earned him a start in the second annual All-Star game at New York’s Polo Grounds on July 10th. That was the game in which National League starter Carl Hubbell struck out Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons and Joe Cronin in succession. Bill Dickey then stroked a single, bringing up Gomez, who struck out. Afterwards, Lefty was perturbed with Dickey, saying “If Bill had struck out, Hubb would have struck out seven of the greatest hitters in history.”39

Gomez did not fare much better on the mound during that game, giving up a lead-off home run to Frankie Frisch and then a gargantuan upper deck blast to Joe Medwick in the third with two on. He left after three innings losing 4-0, but the American League came back to win 9-7, taking Lefty off the hook.

During the season, Lefty participated in an experiment up at West Point with Van Lingo Mungo and Carl Hubbell to try to measure the speed of their fastballs. It involved the shooting of a rifle at the same time as they threw a fastball and comparing velocities. According to Lefty, his fastball was clocked at 100 miles per hour, second to Mungo’s.40

Lefty continued his dominance the second half of the ‘34 season and put together his career year, but the Yankees could not catch the streaking Tigers, who won seven of eight from the Bronx Bombers during one two-week stretch. They eventually captured the pennant by seven games. Gomez finished with a stunning 26-5 record, a 2.33 ERA, 25 complete games, six shutouts and 158 strikeouts in 281 innings, to lead the league in each category. He also managed 13 hits for the year, hitting a less than robust .131. But in the process he collected $250 from Babe Ruth, who annually bet him that amount of money that Lefty would not get ten hits for the entire year.41

Gomez was by now known as a big game pitcher and a fierce competitor, in spite of his easygoing demeanor. In fact, at least one of his opponents, Bill Werber, thought Lefty used his good nature to gain a competitive advantage, by hanging around the opposing clubhouse and joking a little too much before he pitched. According to Werber, Gomez was quoted as saying “I talk them out of hits.”42

Following the 1934 season, Lefty, accompanied by June, travelled to Japan with an All-Star team made up of six future Hall-of-Famers to play a series of 18 games against the best players in Japan in the space of one month. The team carried only four pitchers and one of them, Joe Cascarella, was hampered by a severe case of seasickness for much of the trip.43 The tourists were undefeated with Gomez winning five games while throwing 43 innings. Afterwards, the All-Stars traveled to Shanghai and Manilla for three additional games, with Lefty picking up another win in Manilla. Surprisingly, Gomez hit a lusty .412 in 17 official at-bats for the Japan part of the tour.44

After the games in the Philippines, Lefty and June decided on impulse to join Babe and Claire Ruth and Rosie and Bud Hillerich (of the Louisville Slugger bat company) to continue traveling around the globe. They headed south to Bali, where June celebrated her 22nd birthday, and then on to Java, where they spent Christmas Day, to Ceylon, the Suez Canal and the Arabian Sea, before making their way through Europe and to London. They finally docked in New York on March 1, 1935, three months after sailing from San Francisco.45

Gomez reported to spring training a couple of weeks later decidedly out of shape. He soon developed a sore arm. Although he quickly recovered, the months of eating, drinking, and getting little exercise seemed to take its toll. He was inconsistent once the season began and by the All-Star break had only a .500 record. Nonetheless, American League manager Mickey Cochrane selected Gomez to start his third straight All-Star game, and then left him in there for six shutout innings as Lefty scattered three hits in a 3-0 American League victory. That performance remains an All-Star game record for the longest pitching performance and prompted the National League to force a rule change that limited pitchers to three innings in the game.46

The regular season, however, continued to be a disappointment as the Yankees finished second for the third year in a row, three games behind the Detroit Tigers. Gomez finished with a losing record for the first time with 12 wins against 15 losses. His ERA was 3.18, the same as for his banner 1934 season and fourth lowest in the league.

The next season, 1936, was the year that Joe DiMaggio joined the Yankees. It was the beginning of a lifelong friendship for the 27-year-old Gomez, who took the 21-year-old rookie under his wing, rooming with him on the road and teaching him how to dress among other things.47 After the season, Gomez attended a banquet honoring DiMaggio for his spectacular rookie year. After being handed the award, the shy DiMaggio took the microphone and said, “Thank you very much. And now my roommate will say will a few words.” Lefty was nonplussed but quickly recovered and gave a hilarious talk off the cuff.48

DiMaggio’s arrival propelled the Yankees to their first pennant in four years as they ran away from the rest of the league, finishing in first place by a whopping 19 ½ games. Gomez finished 13-7, but his record was deceiving. He battled a sore arm off and on all year and threw only 188 innings, his lowest total since his rookie year. His ERA rose to 4.39, and for the first time he did not record a shutout. He was selected for his fourth All-Star game, but did not pitch.49 Rumors persisted that the 1934 post season tour of Japan was still taking its toll.

Manager McCarthy named Lefty to pitch Game 2 in the World Series against the cross-town New York Giants and Hal Schumacher. The Yankees jumped all over “Prince Hal” and after three innings led 9-0. This was the game that Lefty, armed with a huge lead, stopped the game to watch a plane fly overhead. The final score was 18-4, with Gomez pitching a complete game.50 Lefty even drove in a run with a ninth inning single.

Gomez received another barrage of offensive support in Game 6, defeating the Giants and Freddie Fitzsimmons 13-5 to clinch the Series four games to two. Lefty even contributed another single and run batted in. It was the Bronx Bombers’ first World Series title in four years, and began a string of four straight World Championships.

Gomez’s two-year contract for $20,000 per year expired at the end of 1936. In spite of the Yankees’ World Series victory, Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert attempted to cut Lefty’s salary to $7,500, grousing that Lou Gehrig’s and his barnstorming in Japan after 1934 had cost the team the 1935 pennant. Lefty’s response was typical. He said, “You keep the salary. I’ll take the cut.”51

Lefty finally signed for $13,000 and, when he reported to spring training, appeared to have new life on his fastball and more bite on his curve. He had lost 15 pounds, much of it gained in his round-the-world sojourn two years earlier. By the All-Star break he had won 10 games against 6 losses, and Joe McCarthy selected him to start his fourth All-Star game out of the five played thus far. In three scoreless innings he gave up only a first inning two-out single to Arky Vaughn and was the winning pitcher as the American League swept to an 8-3 decision.52

Gomez finished 1937 with a 21-11 record as the Yankees swept to their second straight pennant by 13 games over the Detroit Tigers. Lefty led the league in wins, earned-run average (2.33), strikeouts (194) and shutouts (six) while finishing second in complete games with 25. The Yankees again faced the Giants in the World Series and won in five games, with Lefty winning Game One 8-1 and the clinching Game Five 4-2..

These Yankees had three Italians from San Francisco: Joe DiMaggio, second baseman Tony Lazzeri, and shortstop Frankie Crosetti. One time Gomez threw to Lazzeri when he should have thrown to Crosetti who was covering third. When he reached the dugout McCarthy demanded an explanation. Lefty said, “There’s too many Dagoes on the field. I got confused.”

“Too many Dagoes?” growled McCarthy. “Maybe I should be thankful you didn’t throw it to DiMaggio in centerfield.”53

Another time, Lefty fielded a ground ball and mistakenly threw the ball to Lazzeri when Tony didn’t have a play. When Lazzeri asked why Lefty had thrown it to him, Gomez said, “You’re supposed to be the smartest guy on the team. I didn’t know what to do with the ball, so I figured you would.”54

While 1937 was certainly one of Lefty’s finest on the field, off the field was a different story. His mother Lizzie passed away in August, and after the World Series, Lefty and June had a well-publicized split, with Walter Winchell announcing on his national radio broadcast that Gomez was seeking a Mexican divorce. After an acrimonious winter and spring, Lefty came to his senses and begged June to take him back. June resisted, but with the help of mutual friend and former heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey, eventually relented and by the middle of the 1938 season, the couple had reconciled.55

Lefty’s off-field troubles almost certainly affected him on the field, and by the end of May his record was an ugly 4 wins and 8 losses. But he finished strong once he convinced June to take him back, going 14 and 4 to finish the 1938 season with 18 wins against 12 losses. He led the league in shutouts with four and finished third in the league in wins and earned-run average (3.22). Gomez was even tapped to start his fifth All-Star game on July 7 in Cincinnati. He pitched three innings and gave up only an unearned run on an error by shortstop Joe Cronin, but was the losing pitcher in a 4-1 American League loss. It was the only All-Star or World Series loss of his career and ended a streak of eight consecutive wins in those two classics against the National League.56

The 1938 Yankees won their third pennant in a row, finishing 9 ½ games ahead of the second place Boston Red Sox, and faced the Chicago Cubs in the World Series. Joe McCarthy picked Gomez to pitch the second game, at Wrigley Field. Before the game, Lefty was visiting with June at the railing of the stands, with photographers snapping photos. One reporter, who was unaware of their reconciliation, later asked Lefty what June was doing there.

Lefty replied, “Well, she’s not here to pitch.”57

Dizzy Dean was the Cubs starting pitcher, and even though he had lost his famous fastball, gave up only two runs in the first seven innings to lead 3-2. Gomez had given up an unearned run in the first and two more in the third. In the top of the eighth, weak-hitting Frankie Crosetti hit an improbable two-run homer to give the Yankees the lead 4-3. Joe DiMaggio hit another homer in the ninth to extend the final score to 6-3. Johnny Murphy pitched the final two innings to record what now would be a save and secure Lefty’s sixth and final World Series victory. The Yankees then won the next two games back in Yankee Stadium to sweep the Cubs and record their third straight world championship.

The beginning of the 1939 season witnessed the tragic decline of Lou Gehrig, baseball’s “Iron Horse.” On May 2, after 2,130 consecutive games, Lou took himself out of the starting line-up. As Captain, Gehrig took the Yankees’ lineup to home plate before the game and there was not a dry eye in the house. When he returned to the dugout, his teammates were somber and silent, not knowing what to do. After a few seconds, Lefty walked over and sat next to Gehrig. “Hell, Lou,” “ he said, loud enough for everyone to hear, “it took fifteen years to get you out of the lineup. Sometimes I’m out in fifteen minutes.” Everyone, including Gehrig, laughed.58

Gomez struggled with arm trouble in 1939 after injuring his back on May 10 when he was knocked down while covering first on a ground ball. The injury caused him to unconsciously alter his pitching motion and, as a result, he battled arm trouble for the rest of his career. After missing a turn, however, he came back and won five straight decisions and was again named to the All-Star team, although he did not appear in the game. On September 24 he tore a muscle in his side while pitching against the Senators in Yankee Stadium and ended up in the hospital, nine days before the World Series was to begin.59 His regular season was finished with 12 wins and 8 losses for a Yankee juggernaut that swept to their fourth consecutive pennant, this time by 17 games.

The Yankees won the first two games of the World Series against the upstart Cincinnati Reds in Yankee Stadium. On the overnight train to Cincinnati, Lefty convinced Joe McCarthy to let him start Game Three, rather than Oral Hildebrand. He lasted exactly one inning, giving up three hits and a run. He had strained his stomach muscle again trying to field an Ival Goodman hit back up the middle and then winced in pain when he struck out in the top of the second.60 It was Lefty’s last World Series appearance. The Yankees went on to win the game 7-3 and then won Game Four to again sweep the Series for their fourth world championship in a row.

Lefty experienced shoulder, neck and knee pain during spring training, but he still was the Yankees’ 1940 Opening Day pitcher on a cold April 19 against the Washington Senators. He was staked to a four-run first inning lead and pitched well for five innings, before leaving the game with shoulder stiffness. He did not pitch again until July.61

During the interim, Lefty sought medical advice from all fronts and, while at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, ran into Dizzy Dean, another sore-armed former flame-thrower seeking medical treatment. On a happier note, June gave birth to the couple’s first child, a daughter they named Verona, on June 15. Lefty was on the field in St. Louis when he got news of his new daughter. As teammates and reporters gathered around and shouted their congratulations, Joe McCarthy walked up and sourly asked, “What’s all this about, Gomez? You haven’t done a damn thing all year.”

“Joe,” Lefty replied, “I must have done something. June gave birth to a baby girl today.”62

Lefty later said that the birth of his daughter was the only good thing that happened to him in 1940. He finished the year with a 3-3 won-loss record and could throw only 27 innings. He was only 31 years old but it appeared his big league career might be over.

The following winter General Manager Ed Barrow was set to trade Gomez to the upstart Brooklyn Dodgers, who had finished in second place in the National League under firebrand manager Leo Durocher. Lefty, however, armed with June and baby Verona, showed up at the Yankee offices and talked Barrow out of it.63 It turned out to be a wise decision.

The Yankees’ streak of four consecutive pennants and world championships ended in 1940 and they began the 1941 season slowly. But buoyed by Joe DiMaggio’s remarkable 56 game hitting streak, the Yankees caught fire and swept to the pennant by 17 games. Although at age 32 not the pitcher he once was, Lefty contributed significantly, winning 15 games against only 5 losses in 23 starts and 156 innings. He threw only eight complete games and had games saved so many times by Yankee reliever Johnny Murphy that he quipped that Murphy had listed him as a dependent on his income tax.64

The Yankees went on to defeat the Dodgers in five games in the World Series. But McCarthy elected not start the best World Series pitcher in history in any of the games. It was a slight that so bothered Gomez that he refused to talk about it for the rest of his days.65

Lefty pitched well, if sparingly, in the 1942 spring training. His fastball was but a memory and he had trouble throwing more than six innings most of the time. When asked how long he thought he could pitch, he quipped, “As long as Murphy’s arm holds out.” On another occasion when asked about his declining fastball, he replied, “I’m throwing just as hard as ever. The ball’s just not getting there as fast.”66 He became a spot starter for the Yankees, who, having not lost any key players to World War II yet, won the pennant by nine games.

For the season, Lefty was used in only 13 games, finishing with 6 wins and 4 losses. His earned- run average was 4.28 and in 80 innings he struck out 41 while walking 65. The loss of his fastball had not helped his control. For the second year in a row he did not appear in the World Series as the Yankees were stunned by the St. Louis Cardinals in five games. In the locker room after the final game, Lefty announced to his teammates that the team party would be held at the Horn & Hardart automat.67

After the season, Gomez was classified 4-F by his draft board because of torn muscles in his shoulder, back, and side. The army put him to work in a General Electric defense plant in Lynn, Massachusetts instead of enlisting him. Then, on January 26, 1943, after thirteen years with the club, the Yankees gave him his unconditional release.68

Before long, however, the Boston Braves managed by Casey Stengel, signed Lefty in the hopes that he still had something in the tank. Although he gave very helpful advice to the Braves young pitchers, the team nonetheless released him on May 19 before he had appeared in a regular season game. His brief stay might have been due to his popping off to Stengel, who, as a National Leaguer, was always pontificating on how John McGraw of the New York Giants did things. One day American Leaguer Gomez ran out of patience with Stengel and said, “Case, the trouble with this National League of yours is that McGraw’s been dead for ten years and you fellows don’t know it.” Five days later Lefty was gone.69

Clark Griffith of the Washington Senators soon called and gave Gomez a final chance. On May 30, Lefty was named to start the second game of a doubleheader against the Chicago White Sox in Griffith Stadium. It was of some irony that his opposing pitcher was Thornton Lee, whom Lefty had beaten out for the final Class C roster spot with the Salt Lake City Bees in 1928.

Lefty lasted 4 2/3 innings, giving up four hits, four runs and five walks without a strikeout. Lee pitched a complete game six-hitter to beat Gomez 5 to 1. It was Lefty’s last major league appearance. The Senators kept him on the roster for another five weeks before releasing him on July 6. This time no one else came calling.

After the dust settled, Gomez took a job as recreational director for a defense company in lower Manhattan and signed with the semi-pro Brooklyn Bushwicks for $200 a week. In the fall he participated in a USO tour of Africa and Italy along with such notables as Joe E. Brown, Humphrey Bogart and former heavyweight champion Jack Sharkey, visiting hospitals and even front lines to bring some cheer to soldiers.70

Upon his return to the States Lefty again worked for defense companies for the remainder of the war. In the fall of 1945 a wealthy Venezuelan industrialist named Tovar hired Gomez to come to Caracas to give pitching clinics to Latin players and black Americans who were playing there to avoid the segregation of U.S. baseball. Tovar and others formed the first Venezuelan professional league that winter and Lefty became the first manager of Cerveceria Caracas, even though he spoke no Spanish and the players didn’t speak English.71

After the 30-game season, Lefty and June returned to New York in the early spring. Almost immediately, he was asked to step in as the pitching coach for the Newark Bears, the Yankees’ top farm club. Then in mid-June the organization asked Lefty to take over as manager for the Binghamton Triplets, their Class A team, because the manager there had resigned. Although he had future Yankees stalwarts Jerry Coleman and Vic Raschi on the club, the team overall was woeful and in the cellar, finishing 45 ½ games out of first place.72

Undaunted, Lefty returned to manage the Triplets in 1947. In spring training in Edenton, North Carolina, he had a young 18-year old southpaw pitcher, Ed “Whitey” Ford for a time. Gomez had a 10 o’clock curfew and one evening Ford and his roommate decided to ride the Ferris wheel at a nearby carnival, leaving time to get back to the hotel by ten. They ran into a problem when the Ferris wheel operator wouldn’t stop the wheel, despite the players’ protestations. When they finally arrived back at the hotel at 10:05, Lefty was waiting in the lobby and fined them each five dollars.

Years later, Ford overheard Lefty telling Joe DiMaggio about the time he had paid the Ferris wheel operator to keep the wheel going until ten, so that he could extract a fine from his two rookies. Ford immediately demanded his ten dollars back. When Lefty laughingly forked it over, Ford said, “Thanks you SOB. You only fined me five.”73

The ‘47 Triplets got off to a miserable start, losing eight straight games in consecutive home-and-home series with the Utica Blue Sox, leaving Lefty contemplating, as he put it, “looking for other work.”74 The team ended up in the cellar again, this time finishing 39 games behind the pennant-winning Blue Sox. After the season, Lefty, June and their two children (son Gery had been born in 1942) traveled to Cuba where Lefty managed the Cienfuegos team in the Cuban Winter League. There he helped Dodger prospect Carl Erskine work on his curve and also doubled as the pitching coach for the Universidad de La Habana baseball team.75

Back in the States, Lefty spent a year as a roving pitching instructor for the Yankees’ farm system before taking a sales job with Wilson Sporting Goods, which had contracts with many of the major league clubs for uniforms, gloves, baseball spikes, and other equipment. The job was a natural fit for the affable, outgoing Lefty and he almost immediately became Wilson’s top salesman. He would stay with the company for more than thirty years, logging more than 100,000 travel miles a year.

Lefty was a fixture at the World Series each year, representing Wilson. In 1953 he ran into Carl Erskine in the Dodgers’ dugout before the Series opener in Yankee Stadium. The two exchanged news about their respective families and Lefty mentioned that their baby Duane, who had been born earlier in the year, was six months old and doing fine. Sportswriter Jack Lang overheard the conversation and hollered, “A baby? Lefty, aren’t you a little old to be having a baby?”

Quick as a wink, Lefty shot back, “It was my arm that went dead.”76

Gomez continued to be in great demand for banquet speeches and appeared on a number of television quiz and game shows, including What’s My Line. He also twice appeared as a Johnny Carson guest on The Tonight Show. He became very involved in Babe Ruth League youth baseball, serving on the board for over twenty years and working closely with the Babe’s widow Claire Ruth. In 1958 he accompanied umpire Jocko Conlan on an extensive three-month tour of Latin America, giving baseball clinics in Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, and Central and South America.

In 1965 Sandy Koufax made national headlines by refusing to pitch on Yom Kippur, which happened to coincide with the first game of the World Series between the Los Angeles Dodgers and the Minnesota Twins. Don Drysdale started for the Dodgers instead, and was knocked out of the game by the Twins’ six-run barrage in the third inning. Afterward Gomez, who was attending the World Series as usual, said to Dodger manager Walter Alston, “I’ll bet you wish Drysdale was Jewish, too.”77

Surprisingly, Lefty was not inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame until 1972 when he was a unanimous selection of the Veteran’s Committee. When notified, Lefty said, “It’s only fair. After all, I helped a lot of hitters get in.”78

But the great joy of his Hall of Fame selection was tempered by a terrible tragedy the following year. The Gomez’s youngest son Duane was killed in a competitive motorcycle race in August 1973 when he swerved to miss a fallen motorcycle rider in his path and crashed into an embankment.79

In October 1976 Lefty experienced chest pains while playing in a golf tournament and had bypass surgery the following January. In the intensive care unit after the surgery his doctor told him he’d had a successful triple by-pass. Lefty quipped, “Well, that’s the first triple I ever got in my life.”80

After his Hall of Fame induction, Lefty never missed an induction weekend in Cooperstown, enjoying swapping stories with old-timers like Bill Terry, Carl Hubbell, Bill Dickey and others. In 1979 Lefty and Hubbell acted as honorary captains for the 50th All-Star game held in Seattle. Then, in 1983, he threw out the first pitch at the 50th anniversary of the first All-Star game, which was held in Comiskey Park just like the inaugural game. In 1982 Lefty and June flew to Japan to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1934 post-season tour..81 While there Lefty threw out the first pitch at a Japan Series game.

In February 1987 Lefty was again hospitalized with chest pains. His condition was complicated by pneumonia and on February 17 he passed away at the age of 81, just nine days short of his 55th wedding anniversary.

Lefty left this world still making others smile. Near the end his doctor leaned over his bed and said, “Lefty, picture yourself on the mound, getting ready to throw a fastball. On a scale of one to ten, how severe are your chest pains?” Lefty responded, “Who’s hitting, Doc?”

A few days after Lefty died, June was going through his billfold when she discovered a photo of Duane and his girlfriend in tux and gown just before going off to the senior prom. Underneath the photo was a ten dollar bill that Lefty had given Duane before his fatal motorcycle race. A doctor had found the bill in Duane’s pants pocket, and Lefty had carried it with him the rest of his life.82

Sources

Alexander, Charles C., Breaking the Slump – Baseball in the Depression Era (NewYork: Columbia Univ. Press, 2002).

Allen, Lee, The Hot Stove League (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1955).

Allen, Maury, Where Have You Gone, Joe DiMaggio? (New York: E.P. Dutton & Co., 1975).

Auker, Eldon, with Tom Keegan, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms, (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2001).

Broeg, Bob, “Gomez Fast with Baseball or Quip,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Feb. 23, 1989, at p. 5D.

Cramer, Richard Ben, Joe DiMaggio – the Hero’s Life (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000).

Daley, Arthur, Times At Bat – A Half Century of Baseball (New York: Random House, 1950).

DiMaggio, Joe, Lucky to Be a Yankee (New York: Rudolph Field, 1946).

Durso, Joseph, DiMaggio, the Last American Knight (Boston: Little Brown & Co., 1995).

Fitts, Robert K., Banzai Babe Ruth – Baseball, Espionage, & Assassination During the 1934 Tour of Japan (Lincoln: Univ. of Nebraska Press, 2012).

Freedman, Lew The Day All the Stars Came Out – Major League Baseball’s First All-Star Game, 1933 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2010).

Freedman, Lew, DiMaggio’s Yankees – A History of the 1936-1944 Dynasty (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2011).

Gomez, Verona & Lawrence Goldstone, Lefty – An American Odyssey (New York: Ballantine Books, 2012).

Graham, Frank The New York Yankees (New York, G. Putnam & Sons, 1943).

Gross, Milton, Yankee Doodles (Boston: House of Kent Publishing Co., 1948).

Henrich, Tommy with Bill Gilbert, Five O’Clock Lightning – Ruth, Gehrig, DiMaggio, Mantle and the Glory Years of the NY Yankees (New York ; Birch Lane Press, 1992).

Johnson, Lloyd & Miles Wolff, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, NC: Baseball America, Inc., 2d ed. 1997).

Liebman, Glenn, Baseball Shorts – 1,000 of the Game’s Funniest One-Liners (Chicago: Contemporary Books, 1994).

Meany, Tom, Baseball’s Greatest Pitchers (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1951).

Meany, Tom, The Yankee Story (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., 1960).

Porter, David, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports – Baseball, Revised and Expanded Edition (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000).

Rogers III, C. Paul, “Lefty Gomez: The Life of the Party,” Elysian Fields Quarterly, Winter, 2001.

Rogers III, C. Paul, “Gomez, Vernon Louis (“Lefty”)” in The Scribner Encyclopedia of American Lives – Sports Figures, Volume 1, Jackson, Kenneth, T. volume editor (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 2002).

Robinson, Ray, The Greatest Yankees of Them All (New York: Putnam Publishing Group, 1969).

Smith, Ira, Baseball’s Famous Pitchers (New York: A.S. Barnes & Co., 1954).

Tatko-Peterson, Ann, Top 25 Athletes of the East Bay – No. 19: “Lefty” Gomez, Contra Costa Times, Feb. 6, 2006.

Tofel, Richard J., A Legend in the Making – the New York Yankees in 1939 (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2002).

Tullius, John, I’d Rather Be a Yankee – An Oral History of America’s Most Loved and Most Hated Baseball Team (New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., 1986).

Vincent, David, Lyle Spatz, & David W. Smith, The Mid-Summer Classic – The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

Werber, Bill & C. Paul Rogers III, Memories of a Ballplayer – Bill Werber and Baseball in the 1930s (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 2001).

Notes

1 Gomez, Verona & Lawrence Goldstone, Lefty – An American Odyssey, at pages 105-06.

2 Smith, Ira, Baseball’s Famous Pitchers, at page 226.

3 Robinson, Ray, The Greatest Yankees of Them All, at pages 130-31.

4 DiMaggio, Joe, Lucky to Be a Yankee, at page 155.

5 Some accounts have the umpire as Bill McGowan, see Rogers III, C. Paul, “Lefty Gomez, the Life of the Party, Elysian Fields Quarterly, Winter 2001, at page 38, while others have the umpire as Bill Summers, see Auker, Eldon, Sleeper Cars and Flannel Uniforms, at page197; Daley, Arthur, Times at Bat – A Half Century of Baseball, at page 128. On another at bat against Feller, Gomez took three consecutive fastballs for called strikes. After the third strike, he said to the umpire, “That last one sounded low.”

6 Ibid., at page 40; Freedman, Lew, The Day All the Stars Came Out – Major League Baseball’s First All-Star Game, 1933, at pages 64-65; Tullius, John, I’d Rather Be a Yankee, at page 112.

7 Rogers III, C. Paul, Elysian Fields Quarterly, op. cit., at page 40.

8 In later years, Gomez had a quip about his birth. He said that his first name was actually “Quits” because when his father first came in and looked at him after he was born, he told his wife, “Let’s call it quits.” Porter, David, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports – Baseball, Revised and Expanded Edition, at page 562.

9 Gomez,Verona, op. cit., at pages 4-5.

10 Ibid., at pages 11-12.

11 Ibid, at pages 15-17.

12 Ibid, at pages 19-20.

13 When he was 15 or 16, Gomez was hired to pitch an exhibition game against a team of touring players from the Negro Leagues and pitched against Satchel Paige. Ibid., at page 33.

14 Ibid, at page 40.

15 Ibid, at pages 40-41.

16 Ibid, at pages 47-58.

17 Ibid, at page 67.

18 Ibid, at page 71.

19 Ibid, at page75.

20 Ibid, at pages 79, 87-88.

21 Ibid, at pages 89-91.

22 Ibid, at page 99.

23 Ibid, at page 102.

24 Ibid, at pages 102-03.

25 Ibid, at pages 104-07.

26 Ibid, at pages 115-16.

27 Ibid, at pages 117-18.

28 Ibid, at pages 120-21.

29 Ibid, at pages 135-36.

30 Lefty’s response was, “Tomorrow! Who do you think I am, Iron Man McGinnity?” Ibid; Meany, Tom, Baseball’s Greatest Pitchers, at pages 65-66.

31 Rogers III, C. Paul, Elysian Fields Quarterly, op. cit., at pages 41-42; Meany, Tom, op. cit., page 72.

32 Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at pages 150-51.

33 Ibid, at pages 153-54.

34 Ibid, at page 156.

35 Ibid, at page 164.

36 Ibid, at page 168.

37 Vincent, David, Lyle Spatz, & David W. Smith, The Midsummer Classic – The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game, at page 4.

38 Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at page 175.

39 Ibid, at page 176.

40 Ibid, at pages 175-76.

41 Ibid, at page 177.; According to Gomez, one year he beat out a slow roller to third on the final day of the season for his tenth hit. Babe Ruth came rushing off the bench to argue that Lefty had missed first base. Henrich, Tommy, with Bill Gilbert, Five O’Clock Lightning, at page 90.

42 According to Werber, he once ordered popped Gomez on the arm and ordered him out of the Red Sox clubhouse before a game in Yankee Stadium. Lefty gave Werber a hurt look and left. Werber, Bill & C. Paul Rogers III, Memories of a Ballplayer – Bill Werber and Baseball in the 1930s, at page 117.

43 Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at page 183.

44 Robert K. Fitts, Banzai Babe Ruth – Baseball, Espionage, & Assassination During the 1934 Tour of Japan, p. 274-75.

45 Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at pages189-92.

46 Vincent, David, op. cit., at page 17.

47 Allen, Maury, Where Have You Gone, Joe DiMaggio?, at pages 36, 62-63, 112; Durso, Joesph, DiMaggio, the Last American Knight, at pages 107-08, 140, 150-51, 261; Henrich, Tommy, op. cit., at page 24.

48 Cramer, Richard Ben, Joe DiMaggio – the Hero’s Life, at page 108; Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at page 206.

49 Ibid, at page 210.

50 Ibid, at pages 212-13.

51 Rogers III, C. Paul, Elysian Fields Quarterly, op. cit., page 37.

52 Vincent, David, op. cit., pages 28-31.

53 Rogers III, C. Paul, Elysian Fields Quarterly, op. cit., at page 39; Henrich, Tommy, op. cit., page 28-29. Another version has Gomez throwing the ball wildly over second base directly at Joe DiMaggio in centerfield. When manager McCarthy asked who he was throwing it to, Gomez reportedly said, “Someone yelled, ‘Throw it to the Dago,’ but no one said which Dago.” Cramer, Richard Ben, op. cit., at page 108; Freedman, Lew, DiMaggio’s Yankees, at page 28.

54 Henrich, Tommy, op. cit., at page 28.

55 Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at pages 226-241; Freedman, Lew, DiMaggio’s Yankees, op. cit., at page 33-34.

56 Vincent, David, op. cit., at pages 34-38.

57 Rogers III, C. Paul, Elysian Fields Quarterly, op. cit., at page 43; Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at page 245.

58 Ibid, at page 250.

59 Tofel, Richard, A Legend in the Making – the New York Yankees in 1939, at page 187.

60 Ibid, at pages 207-08.

61 Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at page 261.

62 Ibid, at page 262.

63 Ibid, at page 265.

64 Ibid, at page 274.

65 Ibid, at page 276.

66 Rogers III, C. Paul, Elysian Fields Quarterly, op. cit., at page 41; Tullius, John, op. cit., at page 112.

67 Henrich, Tommy, op. cit., at page 28, 138.

68 Gomez, Verona, op. cit, at pages 284-86.

69 Daley, Arthur, op. cit., at page 130; Meany, Tom, op. cit., at page 71; Tullius, John, op. cit., at page 112.

70 Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at pages 291-92.

71 Ibid, at pages 296-99.

72 Ibid, at page 300; Johnson, Lloyd & Miles Wolff, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2d ed., at pages 1945-46.

73 Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at page 302; Durso, Joseph, op. cit.,at page 185-86; Rogers III, C. Paul, Elysian Fields Quarterly, op. cit., at pages 42-43.

74 The Utica club was loaded with future Philadelphia Phillie Whiz Kids Richie Ashburn, Granny Hamner, Stan Lopata, and Putsy Caballero and swept to the pennant by ten full games. Ibid, at page 42.

75 Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at pages 304-07.

76 Ibid, at page 322, Rogers III, C. Paul, Elysian Fields Quarterly, op. cit., at page 43.

77 Ibid.

78 Henrich, Tommy, op. cit., at page 88.

79 Gomez, Verona, op. cit., at pages 352-53.

80 Ibid, at pages 357-58.

81 The promoters apparently moved the celebration up by two years since so few participants were still alive. Ibid, at pages 361-63.

82 Ibid, at pages 355-56.

Full Name

Vernon Louis Gomez

Born

November 26, 1908 at Rodeo, CA (USA)

Died

February 17, 1989 at Greenbrae, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.