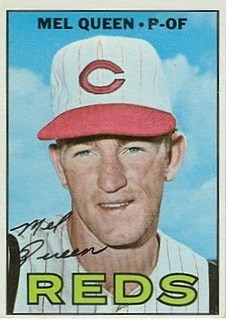

Mel Queen

An infielder, outfielder, pitcher, coach, manager, scout, farm director and baseball executive, Melvin Douglas Queen, had been all of them. He has the distinction of having entered the major leagues as an outfielder and finishing as a pitcher. The son of a former major leaguer, Mel was born on March 26, 1942, in Johnson City, New York. His father, Melvin Joseph Queen, was a pitcher in the Yankees and Pirates organizations from 1938 until his retirement in 1955.

An infielder, outfielder, pitcher, coach, manager, scout, farm director and baseball executive, Melvin Douglas Queen, had been all of them. He has the distinction of having entered the major leagues as an outfielder and finishing as a pitcher. The son of a former major leaguer, Mel was born on March 26, 1942, in Johnson City, New York. His father, Melvin Joseph Queen, was a pitcher in the Yankees and Pirates organizations from 1938 until his retirement in 1955.

Johnson City lies just to the west of Binghamton, New York. It was named in honor of the founder of the Endicott Johnson Company, the shoe manufacturer. Mel, one of three children born to his father Mel and mother, was of Dutch, English, Scottish and Italian descent.

Mel’s family moved to California in the early 1950s when his father was playing for the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League. The family initially spent a good amount of time in Lakewood and then moved north where Mel attended San Luis Obispo High School and was a three-letter man. During his sophomore year Mel played at both quarterback and halfback for the football team and being able to jump, played center on the basketball team. But Mel decided to devote his time and talents to baseball and did not return to the hoops or gridiron. In his senior year he batted .425 and named the team’s Most Valuable Player. A 1960 graduate, Mel was twice named All-League and All-California Interscholastic Federation shortstop.

As a youngster Mel would accompany his father to the ballpark. He would shag flies in the outfield. A baseball rat he would spend a lot of time at Forbes Field. The Pirates’ manager Danny Murtaugh recalled having games of catch and pepper with the young Mel. When his Dad played for the Hollywood Stars, Mel would go to Gilmore Field.

But Mel’s father did not try to push Mel toward being a baseball player. The senior Queen would tell Mel: “If you want to play major league baseball you will have to make it on your own.” Upon graduation from high school in June 1960, Mel was the subject of much competitive bidding from virtually all the major league teams. The Reds wanted him and reportedly paid Mel $100,000 to sign. Part of the deal was a $5,000 Corvette. Mel at six feet and one inch threw with his right hand and batted from the left side of the plate and weighed in at about 190 pounds at signing. Mel was signed June 19, 1960, to a Reds contract by Bobby Mattick, a former infielder in the Cubs and Reds organizations who later went on to manage the Toronto Blue Jays in 1980 and 1981. Signed to play the infield, Mel made some great outfield plays in the Instructional League. The coaches thought he was a natural even though Mel had no prior experience.[i]

After signing, Mel was sent to Palatka in the Florida League where he started his professional career at third base. In 1961 Mel played third base for Topeka in the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League (IIIL). In 1962, after a few games starting at third playing for Macon in the South Atlantic (Sally) League, Mel was positioned in the outfield and was chosen to play the outfield in the league’s All-Star game. Then in 1963 Mel had his breakout year playing for the Triple A San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League (PCL).

According to a Reds press release by their director of publicity Hank Zureick, general manager Eddie Leishman of the San Diego Padres was quoted as saying that “Mel played a great center field but I believe he is a better right fielder. He has good instinct, gets a very good jump on the ball and has a terrific throwing arm, and he swings an authoritative bat.” The same press release quoted Padre coach Whitey Wietelmann as stating: “Queen has an arm as strong as Rocky Colavito’s…He certainly has a quick bat.” Despite a delayed start, Mel played 134 games for the Padres in 1963, batting .260 with 25 homeruns. Mel was tabbed as the ‘top major league prospect (other than pitchers) in the PCL in 1963 and the outfielder with the best throwing arm’ by the managers.

Mel’s late start was due to an auto accident that occurred when Mel attempted to drive from Spring Training in Tampa to San Diego – 3,000 miles non-stop. He dozed, fell asleep at the wheel, crashed head-on into a car and trailer. Mel felt as though he had been hit with a bat. A passing truck driver stopped and took Mel for dead. When he went with his friends to the yard where the remains of his vehicle lay, the attendant could not believe that the man in front of him was the driver of the car. Mel still sports a scar on the bridge of his nose as a memento of that event.

In April 1964, shortly before Mel’s major league debut, Earl Lawson, a Cincinnati Reds beat writer for the Cincinnati Post and a frequent contributor to the Sporting News, wrote that Mel’s hero was Mickey Mantle. (Mel would eventually have the opportunity to pitch to Mantle in a Spring Training game and walked him.)[ii] Lawson went on to quote manager Fred Hutchinson as saying “Mel owns a potent bat and one of the game’s best arms, the kid’s going to be a real good hitter. He has the good compact swing…no wasted motion.” And he quotes Mel’s former minor league manager Eddie Leishman as stating “I don’t think he’ll ever hit for a high average, but he’ll always have a lot of homers and runs batted in. He still takes too many pitches. Anyone who has as much pop in his bat as he does, should be swinging all the time.”

Mel made his major league debut on opening day April 13, 1964, as a pinch hitter against Ken Johnson of Houston. Mel related how he hit a bullet to center field that appeared to be a sure double. But Jim Wynn made the diving catch to rob Mel of his first hit. Eleven days later Mel got another chance to pinch-hit. This time against the Giants and Juan Marichal, Pete Rose was in the on-deck circle when Mel went up to bat for the pitcher. Rose was telling Mel to watch out for the fastball. But Juan so surprised Mel with a screwball that he started to swing and then pulled back hitting himself in the head with his own bat! Mel said later that Pete Rose could not stop laughing. On the next pitch Mel had his redemption and his first major league hit with a ground ball single up the middle. The Giants pounded the Reds that day, 15-5.

On August 1, 1964, against the Cards and the score at 3-3, Mel pinch-hit a three-run homer off Bob Gibson. It was his second and last career home run. The blast in the top of the seventh proved to be the winning runs as the Reds held on to win, 6-5. When he next faced Gibson on September 7, Mel was sure that Gibson would go at him. But Gibson would later admit to Mel that there was no reason to go at Mel for hitting a bad pitch over the fence.

In that September 7 game Mel started in right field and went hitless in three plate appearances. Mel was able to work Gibson for a walk in one of those at-bats.

Mel realized early in his career with the Reds that he might not be able to find a place in the outfield that had Frank Robinson (replaced by Deron Johnson in 1966), Vada Pinson, and Tommy Harper. According to the June 10, 1964, edition of the Dayton Daily News, Mel requested of the Reds coach Jim Turner, a former major league all-star pitcher, that he give him the opportunity to throw and receive daily pitching lessons so that he could follow in the footsteps of Bucky Walters and Bob Lemon, both of whom started their major league careers as third basemen. In 1965 Mel was back in the minors for most of the season. Mel saw all of three plate appearances over five games for the Reds. He played the outfield in 139 games at triple A San Diego in the PCL.

Mel went off to Nicaragua to play winter ball. He experienced success as he hit over .300 (.343) for the first time in any league since he’d entered professional baseball. Mel related to this writer his encounter with Nicaraguan President and dictator Luis Anastasio Somoza Debayle. Somoza was in office from 1956 until his death in 1967. According to Mel, prior to the start of a game the team manager told the players that they would not get paid for some additional games. Mel refused to play unless he was paid. He was the only holdout. The team lost both games that Mel sat out.

During the night Mel was awakened by a knock on his door. It was officers of Somoza who brought him to the Presidential Palace. Somoza, who owned the team, wanted to know why Mel did not play. After Mel explained “no pay-no play,” the dictator looked at Mel and said, “Do you know who I am?” Mel, fully aware of the situation, responded: “Yes, and you could have me killed and no one would know it. So go do what you want, but I am not afraid of you.” Somoza, impressed by Mel’s nerve, came back at him, “I like you!” Mel returned to action, as Somoza paid the players.

Mel started the 1966 season with the Reds as a utility outfielder and pinch-hitter. As such he would often be called upon to warm up pitchers in the bullpen. It was also a common occurrence for spare outfielders to be called upon to pitch batting practice. Dick Peebles of the Houston Chronicle wrote on April 24, 1967, quoting Mel. “My fast ball would really move and the guys would talk about it. I can make it take off or sink depending on how I hold it.” Mel was able to throw at 95-97 MPH. Larry Merchant of the New York Post wrote on May 9, 1967, that Mel had one of those shotgun right field arms. So when Reds Manager Don Heffner asked for batting practice volunteers Mel stepped up.

Outfielder Deron Johnson was really struggling to hit high fastballs. Johnson complained about the soft pitches being thrown by the Reds batting practice pitchers. Deron wanted to know if there was anybody who could throw hard in batting practice. Mel said: “Gimme the ball and let me try it.”[iii] When Mel pitched to him in batting practice, Johnson missed more pitches than he could hit.[iv] Merchant went onto quote Mel. “The balls I was throwing were scuffed up a little so they really move around. I guess Heffner thought I could throw liked that all the time.”

On July 15, after a short stint on the disabled list, Mel was sent to the bullpen by new Reds Manager Dave Bristol (replacing Heffner during the All-Star break). The Reds were losing badly to the Cards. Mel thought he was to be the bullpen catcher but instead was told to warm up. It was to be his first major league pitching assignment. Queen came in and retired the Cards in order, striking out the last two batters he faced. The first batter, Charley Smith, was thrown out by the catcher on a tap out in front of the plate. “The guy has a quick slider and he struck me out with a heckuva curve,”[v] chimed in Dal Maxvill, Queen’s first strikeout victim. He then whiffed Cards’ second baseman Julian Javier.

One of the biggest things he had to learn was to throw like a pitcher and not an outfielder. He had previously warmed up before games by throwing sliders and curves. He attributes some of that initial success to the batters fearing he may lack control as a newly converted outfielder to pitcher. Five days later he was summoned for the ninth to protect a one run lead over the Cubs. He struck out the side and picked up his first major league save. Sportswriter Earl Lawson quoted the Cardinals’ Manager Red Schoendienst as saying: “You’ve got to like any kid who can throw as hard as Queen does and besides that, he throws strikes.”[vi]

Joe Gergen, UPI Sports Writer, in March 1967 quoted Mel as stating: “I find the mechanics of pitching come to me fairly easily.”

Oddly Mel had headaches when he first started his conversion to pitching. The cause of the headaches was some cells in his spinal fluid that should not have been there. It put him in the hospital for ten days at the beginning of June 1966 and on the disabled list for six weeks until the headaches disappeared. Mel remembered injuring his arm as a freshman in high school when he and a fellow teammate, on the first day of practice, attempted to see who could throw the ball the farthest. Something popped in his elbow so he switched to first base and shortstop. The strength in his throwing arm did not return until his high school years ended.[vii]

To practice his pitching, Mel went on to play winter ball in Venezuela, pitching for the Aragua team. Mel established himself as the top pitcher in the league winning seven of nine decisions with five shutouts and finishing with an ERA of 0.76. That winter season major league pitchers Luis Tiant, Jim McGlothlin, and Bill Conners were among those who joined Mel in Venezuela. Mel sported facial hair while a member of the Aragua team and was labeled “El Hombre” – The Man by the fans.

Carl Ermer, who went onto manage the Twins in 1967 and 1968, was Mel’s manager in Venezuela. Coincidentally, Jim Lonborg of the Red Sox was Mel’s winter teammate. There was irony in that, because Mel had married and divorced Jim’s sister. Lonborg was a teammate at San Luis Opispo High School. At graduation Mel was honored for baseball and Lonborg for basketball. Ermer expressed deep pride in the fact that he was helping to develop both Jim and Mel as pitchers. Ermer was instructed by the Reds to have Queen play in the field – first base and the outfield between starts. But Mel was not to do anything in the field that would hurt his arm. Mel told Ermer, “I won’t get a chance to pitch in the majors. We’re wasting our time.”[viii]

Ermer disagreed. He believed that Mel, as a starter, had the stuff to win 15 games in the big leagues and that by starting out relieving he would eventually start. Mel believed that there were too many good pitchers already on the Reds roster for this to happen. Ermer again disagreed, reiterating his belief that Mel was as good as any other starter.

El Hombre became an attraction at the Venezuela ballgames, not only for his pitching talents but also because of his looks. Mel had decided not to shave or cut his hair. It was an economical way to save a few dollars as he was to be married in 1967.[ix] With his long hair and beard, he had an almost Christ-like appearance, according to his manager Ermer. Along the way Ermer made one change in Mel’s pitching style. He insisted that Mel take a little time and quit hurrying his pitches. The club owner, recognizing Mel’s popularity, wanted Ermer to pitch him every third day. Mel was eager to do this as he was promised a bonus of $800 accordingly. Ermer was adamant that he follow the Reds’ directive and that he would quit if Mel did in fact pitch out of turn. He reiterated how Mel was concerned about his elbow every time out. How Mel would come back to the dugout and say how awful his arm felt. Usually after a couple of innings Mel would forget about his pain and continue all the way. Mel remembered once being offered a $5,000 bonus to pitch both ends of a doubleheader. He was talked out of it by his teammate Dick Egan, who was a relief pitcher with the Tigers, Angels and Dodgers. Mel also recalled being promised a bonus of $1,000 for each extra win if he pitched out of turn.

Mel’s most memorable baseball moment was to occur in 1967. He was to get his first major league start. On April 16 before the second game of a doubleheader scheduled starter Jim Maloney took ill and had to sit out prior to game time. Mel went out and pitched a complete game shutout, allowing just six hits by the Giants batters. Mel had no time to do anything special in preparation for his first start. “I hadn’t taken time to shave that morning and I thought maybe I didn’t look too good.”[x] He was a little nervous but mainly excited. Mel related how he warmed up and before he knew it the game was over. Along the way and two hours and 17 minutes later he had struck out eight Giant batters including all three hitters (Jesus Alou, Ken Henderson and Norm Siebern) he faced in the ninth. (It is of interest that this start came after Mel had only pitched one inning in the young season on April 14 against Houston. In that game Eddie Mathews powered a home run after Mel had allowed two batters to reach base.) For his successful performance Mel was named National League Player of the Week.

The 1967 season was to be a magical episode in Mel’s pitching career. On May 16 Mel pitched a gem against the Pirates, a complete-game win that featured throwing eight scoreless innings until the Pirates capitalized on an error by second baseman Chico Ruiz in the ninth to put three runners across the plate. Only one of the three runs was earned as Mel struck out nine Pirates. “I won this one for my Dad. He pitched for the Pirates, you know, and he was upset when I hurt my arm in high school. He always said I had a better future as a pitcher and I know this will make him happy,” Mel said later.[xi] It was Mel’s fifth win of the season against one loss and lowered his ERA to 1.85.

Roberto Clemente, to whom Queen’s throwing arm was compared when Mel was an outfielder, praised Queen after the game, saying: “I knew he was fast but he also has good breaking pitches and good control”[xii]

On June 16, pitching if front of his father at Los Angeles’ Dodger Stadium, Mel pitched a complete-game four-hitter to beat the Dodgers 3-2, and bring his record to 8-1. It was his fourth complete game of the season. Mel would finish with six for the 1967 season, his career total. When the season ended Mel had compiled 14 wins over 195.2 innings, an ERA of 2.76 (10th in the National League), and struck out 154 batters while only allowing 52 walks. He completed six games, two of them shutouts. Pittsburgh manager Danny Murtaugh praised Mel’s control pitching. He told Mel that if Mel Sr. had his son’s control he would have won a lot more games than he did.[xiii] Mel Sr. averaged two more walks per nine innings pitched over his career than did Mel Jr.

But along with all the successes came potentially career-ending injuries. During the season Mel suffered a tear of the rotator cuff in his throwing arm. This led to the first of hundreds of cortisone shots that ended after the 1972 season when doctors told Mel he had received his quota. Thus his pitching career would end at the age of 30. In addition to the rotator tear Mel suffered from an attack of pleurisy during 1967 that sent his outstanding mid-season pitching record into a tailspin. The pleurisy caused Mel to have trouble breathing. His legs and his throwing arm weakened as well. Earl Lawson, writing for The Sporting News, reported that Mel was always complaining that something bothered him every time he pitched, even when he was pitching well. So much so that his teammates on the Reds would make fun of mimic him. Mel once said, “If I ever felt real good warming up before a game, I think I’d be scared to death.”[xiv] Mel recalled his Venezuelan teammates as being unmerciful. His manager in the Winter League, Carl Ermer, said that if Mel complained of a sore elbow after warm-ups, we’d figure that Mel would be pitching a shutout. Mel complained throughout his September 8, 1967, start against the Mets in which he allowed only two hits and two walks. Mel went the distance for the Reds in a 3-0 victory.[xv] Mel thought he was ballooning his pitches to the plate over the first three innings. When the game was over he had struck out 10 batters for the second game in a row. Mel would joke about his ailments stating that when he first started to pitch the pain was in the forearm and then moved to the shoulder, so that with the way it is moving it should completely leave his body by next year.

Arm trouble caused Mel to pitch only 30 innings total for the Reds over two seasons, 1968 and 1969. At Spring Training 1969 Mel was looking good and appeared to be ready for a comeback. Pitching coach Harvey Haddix warned Mel that ‘if you can’t throw, the Reds aren’t going to carry you all season the way they did last year. There is no room on this team for sore arms.’[xvi]

When Reds General Manager Bob Howsam announced that Mel was to be released outright to Indianapolis of the American Association, Mel was deeply disappointed. Mel felt as though his arm was coming around. However, it was his belief that management did not want to wait any longer and take chances given that Mel had arm trouble in prior seasons. Mel did start two games in April 1969 in which he pitched six innings each time. On April 22 against the Houston Astros, Mel got the win as he allowed just two hits in a Reds’ 14-0 victory. Mel’s ERA was at 2.25, but he had quit after five minutes of warm-ups the previous Sunday complaining of a sore arm, and the Reds believed they had eight able-bodied pitchers – Tony Cloninger, Jim Maloney, George Culver, Jim Merritt, Jack Fisher, Wayne Granger, Clay Carroll and John Noriega (who would pitch only 7.2 innings in 1969).[xvii] After the 1969 season Mel was sent to the California Angels for cash.

Mel remained with the Angels for three seasons as a relief pitcher with the exception of three starts during the 1970 campaign. Mel could no longer throw more than a few innings without being in pain. In addition his control was not what it once was. During these three seasons Mel had 13 saves and an ERA of 3.22 in 95 games. The 1971 season was his best season as a reliever with an ERA of 1.78 over 44 games. After the 1972 season Mel was released by the Angels in December. In January 1973 Mel signed as a free agent by the Phillies, but his arm was just too sore and he could no longer receive and play with cortisone shots. Mel did pitch for a short while in the Mexican League with the Poza Ricca team and picked up a win on May 20, 1973, against the Tampico team. But Mel ran out of gas in the sixth inning and had to be replaced.

Mel left baseball to return to his home and family in Morro Bay, California. Mel managed a friend’s seafood restaurant there and was able to spend time with his wife Gail (presently a real estate broker) and his three children. Mel remained out of baseball. He was down on the game after his retirement because of his injury. He did not even want to watch a game in person or on television.

Then in 1979 Mel was ready to come to the game he so loved from childhood. In late 1978 Mel heard that the Indians needed a minor league pitching coach. Dave Bristol, Mel’s former manager in Cincinnati, called the Tribe farm director, Bob Quinn, to recommend Mel for the position. The Indians hired Mel to handle their young arms at class A Waterloo. A year later he was with the class AAA Tacoma team. When the Indians switched class AAA to Charleston, Queen went there for the 1981 season. In 1982 Mel was to back in the big leagues, when he was named the Cleveland Indians pitching coach in November 1981. Cleveland had originally offered the coaching position to Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson after Dave Duncan left the team in a salary dispute. But Gibson had already made other plans.

Queen had received nothing but rave reviews in Florida’s Instructional League. Manager Danny Carnevale said, “Mel has had a profound impact on the pitchers. He took a bunch of kids who were 16-54 at Batavia and got them to the point where we are now 28-14 in this league. You have to be impressed by his work.”[xviii] Mel attributed his success as a pitching coach to his ability as a pitcher to learn all the pitches easily and to be able to read and work the hitters.

Mel managed the 1985 Bakersfield Dodgers, the 2000 Syracuse Sky Chiefs (Toronto farm affiliate), the 2004 High Desert Mavericks (Brewers), and for the final five games of the 1997 season took over the helm of the Toronto Blue Jays after the firing of Cito Gaston. Under Mel’s guidance, the team won four of those five games.

Prior to taking over as manager of the Blue Jays, Mel was their pitching coach starting in 1996 and continued in that role until the end of the 1999 season. During this four-year period the Blue Jays had three consecutive Cy Young award winners – Pat Hentgen once and Roger Clemens twice. After his managerial stint in Syracuse, Mel, under J.P. Ricciardi, was on a “special projects” contract. He was assigned on a case-by-case basis to work with specific minor-league pitchers. He was basically a roving minor league coach. He was also the farm director and a special assignment scout during this time period with the Blue Jays. His most recognized work as a coach is his complete overhaul of Roy “Doc” Halladay as a pitcher in 2001. When I asked Mel what he did, he simply stated that he had Doc speed up his delivery.

The real story was that Mel put Halladay through pitching boot camp using a tough-love approach. He not only changed the mechanics of his delivery and taught him new grips but got into Halladay’s head and changed the pitcher’s mental approach to the game. At times Mel had to verbally abuse him to accomplish his goal of making Halladay into a Cy Young winner in 2003.

In 2008 Mel was appointed the Senior Adviser of Player Development with the Blue Jays, a position he held until May 2011. He had been the director of player development for the Blue Jays when they won back-to-back World Series in 1992-93. As such he traveled to the various clubs in the organization working with coaches, managers and players. He assisted with the placement of the players with the various teams in the Blue Jays organization. Much of his time was spent with the instructional league in Florida. Besides working with three Toronto Cy Young award winners – Halladay, Hentgen and Clemens – he has also worked with Chris Carpenter.

Interviewing Mel was a pleasure. He had many interesting stories and experiences to relate. One of my favorites is hearing how he loaned his car one Spring Training in Tampa, Florida while he was with the Reds. Deron Johnson made the request so that he could go for a night out with Mickey Mantle, who was a friend. The next morning Johnson had no idea where he had left the car. Several days later, while riding on the team bus, Mel spotted it behind a church. Neither Johnson nor Mantle had any idea how it wound up there.

On June 20, 1999, as reported in USA Today, Mel and Jim Fregosi, Toronto manager, got into a scuffle at a late night stadium hotel bar with gangster Joey Merlino, the acting boss of the Philadelphia crime family. Apparently Merlino had a beef with Fregosi. Fregosi suffered a black eye, and Mel came away with cuts and abrasions. That same month Merlino was indicted on charges he conspired with the Boston mob to purchase and distribute cocaine. He was sentenced to 14 years in prison on December 3, 2001, on racketeering charges, including extortion and illegal gambling. He was released from prison on March 15, 2011.[xix]

Mel coined the phrase “hit it at ’em ball.” Apparently Mel, when not feeling well, but pitching well, was known to say that he was able to throw the pitches in such a way that the batters would it right at a fielder. When asked who he liked pitching to and who he did not, Mel replied that he liked the free swinging home-run type hitters. He did not mention any one batter in particular. However, on the “do not like” side he specifically mentioned Don Kessinger of the Cubs. Kessinger was four for 10 plus a walk and sacrifice fly against Mel. Mel did not like contact hitters in general.

When not involved with baseball, Mel enjoyed ocean and river fishing, particularly for striped bass. There is certainly enough ocean surrounding the Morro Bay family home on the California coast.

Shortly after Mel returned in October from the 2010 Florida Instructional League camp, he took ill. He had difficulty speaking, lost weight and underwent surgery shortly before his first interview with me on February 25, 2011. In March he indicated his plans to return to the position he held in the Blue Jays organization. On May 12, 2011, Mel, at home with his family, succumbed to the cancer that had spread to his brain. Mel is survived by Gail, his wife of 44 years, their three children, and nine grandchildren. One child is an installer of tile, one in real estate, and the other in animal control. Mel maintained close contact with his former manager and friend Dave Bristol. They spoke once or twice monthly. Mel also maintained a close relationship with his former student of pitching, Pat Hentgen. There is no better way to end this story of Mel Queen’s life than with the word Mel used to describe to me what Winter League ball was like: Wonderful!

June 15, 2011

Sources

Telephone interviews with Mel Queen, Jr. on February 25 and March 18, 2011.

From Mel Queen’s Hall of Fame Library player file:

1964 Major League Baseball profile sheet

Reds Press Release by Hank Zureick, Publicity Director, 1963-1964

1967 article by Murray Chass

Joe Gergen, UPI Sports Writer, March 1967

Walter L. Johns, Tampa article March 1, 1963

Various articles by Earl Lawson

Dayton Daily News, June 10, 1964

Neal Russo, St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 2, 1964

Lester J. Biederman, The Pittsburgh Press, May 17, 1967

Dick Peebles, Houston Chronicle, April 24, 1967

Larry Merchant, May 9, 1967

Rich Marazzi, “Batting the Breeze,” Sports Collectors Digest, July 18, 1997

Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, March 26, 1968

Ed Rumill, Christian Science Monitor, May 4, 1967

Si Burick, Dayton Daily News, August 30, 1967

Bob Hertzel, San Francisco Enquirer, April 29, 1969

USA Today, June 21, 1999

The Sporting News, March 30, 1968 and September 23, 1967

Various articles by Terry Pluto

Full Name

Melvin Douglas Queen

Born

March 26, 1942 at Johnson City, NY (USA)

Died

May 11, 2011 at Morro Bay, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.