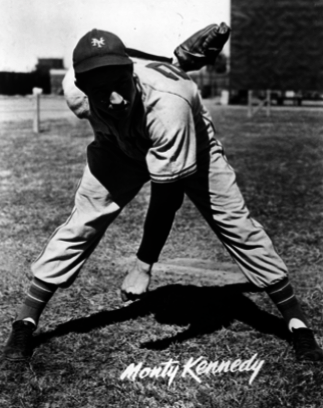

Monty Kennedy

Remembered for his blazing fastball, Monty Kennedy had an abbreviated minor-league baseball career that was quickly interrupted by military service. Perhaps because of this lack of development time, Kennedy struggled constantly with his control during his time with the Giants and the club eventually ran out of patience with him. However, Kennedy displayed flashes of brilliance over short periods, and while he never developed the consistency necessary to become an established part of the Giants’ rotation, he pitched 961 innings during eight seasons in the major leagues.

Remembered for his blazing fastball, Monty Kennedy had an abbreviated minor-league baseball career that was quickly interrupted by military service. Perhaps because of this lack of development time, Kennedy struggled constantly with his control during his time with the Giants and the club eventually ran out of patience with him. However, Kennedy displayed flashes of brilliance over short periods, and while he never developed the consistency necessary to become an established part of the Giants’ rotation, he pitched 961 innings during eight seasons in the major leagues.

Montia Calvin Kennedy was born on May 11, 1922, in Amelia, Virginia, southwest of Richmond. Commonly known as Monty, he was the only son of Garland Britton and Daisy Etta (Anderson) Kennedy.1 He had two older sisters, Hazel, born in 1914, and Gladys, born in 1916, and three younger sisters, Josephine, Mable, and Mollie.

According to census data, the Kennedys lived in the Jackson township in Amelia County. Monty’s parents were both native North Carolinians. Born in 1893, Garland worked as a farmer and Daisy, who was born in 1890, was a housewife.

Monty was a first baseman for his high-school team, as he was left-handed and not a particularly strong fielder. However, he also began pitching regularly during his later years on the team.2 After three years, it appears Kennedy left school and began working as a farmhand.3

In 1942 the Washington Senators played an exhibition game in Richmond and Kennedy was given a tryout with the club before the game. He pitched well, but the Senators passed on the 19-year-old, viewing him as too young and lacking polish as a pitcher.4

However, the tryout put the 6-foot-2, 185-pound left-hander on the radar of the Richmond Colts of the Class B Piedmont League, and they signed Kennedy at a salary of $150 a month.5 He pitched in three games for the Colts, and his lack of experience as a pitcher was evident, as he walked 18 batters in 17 innings.

Kennedy enlisted in the US Army on December 5, 1942. Unexpectedly, the Army provided a great opportunity for Kennedy to gain more experience as a pitcher. While serving in the Army Air Corps, he never left the United States, pitching extensively for the team at Robins Field in Georgia.6 Over three years, Kennedy won 41 games and lost only 10 against opposition that was reportedly composed in large part of major leaguers.7

In 1944, while he was still in the Air Corps, Kennedy had a daughter named Pat.8 Before the 1944 season, the New York Giants reached a working agreement with Richmond, and in 1946, with World War II over, Kennedy reported to Giants spring training in Phoenix, Arizona. Despite his lack of professional experience, his performance while in the Air Corps had attracted the attention of the Giants’ front office.9 Nonetheless, he was viewed as such a longshot to make the team that one reporter said it would be a “postwar miracle” if Kennedy made the club, given he had only 17 professional innings pitched.10

In one of his first spring-training starts, Kennedy allowed three runs against the Boston Braves, walking four and hitting two. Despite his wildness, he looked unhittable when he threw the ball over the plate. One reporter wrote, “If someone hadn’t stuck the bat in the direction of the pitch, they wouldn’t have come close to the ball.”11 In another start, Kennedy’s infielders booted two double-play balls, but manager Mel Ott was impressed by Kennedy’s calmness and demeanor on the mound.12

Kennedy threw harder than anyone else in the Giants’ camp and showed enough promise that the club decided to purchase him from Richmond owner Eddie Moerrs for $25,000.13 In one of his memorable spring-training games, Kennedy faced off against Cleveland’s Bob Feller. Although he still struggled with his control, Kennedy reportedly “displayed more speed, struck out more men and yielded less than one-third the number of hits allowed by Feller.”14 That game helped justify the Giants’ decision to purchase Kennedy, as well as his case to make the big-league team out of spring training.

As word of Kennedy’s blazing speed spread, people began to place significant expectations upon the inexperienced hurler. At one point, several members of the Giants, including Ott, bullpen catcher Grover Hartley, and coach Tom Sheehan dubbed Kennedy the new Carl Hubbell.15 Contrasting Kennedy’s first spring-training appearance to his later ones, Hartley said, “I’ve never seen anything like it in my whole career. That kid has changed overnight.”16

Catcher Ernie Lombardi compared the reaction of hitters facing Kennedy to the way hitters reacted when they faced Johnny Vander Meer. He recalled, “I saw many [hitters] trying for three strikes just to get out of the range of Vander Meer. … They’ve got to look as if they’re digging in. But a lot of them don’t worry too much about that when they might get hit in the head.”17

Kennedy insisted that his control issues in spring training were uncharacteristic. “I’m not naturally a wild pitcher,” he said. “I walked only one man in each of those sixteen-inning games [with the Air Corps], striking out fifteen batters each time. … I really can’t understand what’s going on now except that I feel embarrassed.”18 These comments were supported by the reported statistics from his career in the armed forces, where he averaged only one walk every nine innings.19

Kennedy was eager to learn from the more experienced members of the Giants’ pitching staff. During spring training he’d wake up Hartley at 6:30 in the morning to hear stories and pick up tips from the times when the former Giants catcher had caught Christy Mathewson.20 After his start against Feller, Kennedy remarked, “I realize now that I knew absolutely nothing about pitching when [I was sold].”21

Kennedy took the lessons of Hartley and Sheehan to heart, developing a new pitching stance and an overhand motion. Kennedy believed his new motion gave his pitches more movement and also improved his control.22

Although he was a longshot to make the club’s major-league roster at the beginning of spring training, Kennedy beat the odds and headed north with the club. He was assigned to room with veteran catcher Walker Cooper, who called him one of the best prospects he ever saw.23 Monty made his major-league debut in New York’s third game of the season, on April 18 against the Brooklyn Dodgers. He threw three one-hit innings of relief and was then given the starting assignment on April 25 against the Boston Braves. Kennedy, who wound up with a no-decision, went 5⅓ innings and allowed four runs. However, three of those runs scored when right fielder Willard Marshall misplayed a fly ball into a three-run home run. After the game, Marshall admitted his bad judgment had led to the three runs.24

Kennedy earned victories in his next two starts, which came against the Chicago Cubs and the Braves. He went the distance in both games, each a 5-1 victory. In the two starts he walked 12 and hit two batters, but allowed only 10 hits and one earned run. After the game against the Cubs, Lombardi said Kennedy’s fastball had as much life as any fastball in the big leagues and that, especially considering his age and lack of experience, he had a great feel for his changeup.25 The “Amelia Beauty,” as Kennedy sometimes came to be called, lost his next start, but allowed only two earned runs in eight innings and threw his third straight complete game.

Kennedy was shuffled between the rotation and bullpen in June and then was returned to the rotation in July. He seemed to suffer more than his share of hard luck at times. In a game against St. Louis in early June, the Cardinals scored a run when a pop fly fell between Johnny Mize and Walker Cooper, and another run scored when Mize dropped a throw at first. The Giants won on a ninth-inning homer after Kennedy had left the game.26 After the game, Cardinals pitcher Mort Cooper predicted, “He will be the best lefty in the league in three years.” Dizzy Dean, then a Cardinals broadcaster, said, “It seems we see nothing but lefties here in St. Louis and this kid comes very close to being the best.”27

Those words were prescient, as Kennedy subdued the Cardinals later in the season with a three-hitter.28 However, the best start of his rookie season may have been in August against the Pirates. Kennedy threw a complete-game 10-inning shutout and the Giants prevailed, 1-0. He allowed only five hits and contributed at the plate with a single, a double, and a sacrifice bunt. The only negative was that he walked eight, a symptom of the control issues that would plague him throughout his career.

Over the last two months, Kennedy threw five complete games and allowed one run in each game. In one, he defeated the Cincinnati Reds 4-1 to end a six-game losing streak for the Giants. Kennedy was perfect at the plate with three hits and surrendered the lone run on a Bobby Thomson error.29 He finished the season with a 9-10 record and a 3.42 ERA in 186⅔ innings and was one of three National League rookies to throw at least 10 complete games, along with Cincinnati’s Ewell Blackwell and Joe Hatten of the Dodgers.

Kennedy’s weakness was his control, and he walked a league-leading 116 batters. Some writers also said he had difficulty working his way out of trouble, perhaps because of his inexperience.30 However, Kennedy led the National League with only 7.38 hits allowed per nine innings, demonstrating how difficult he could be to hit against when his stuff was working.

While the Giants held high hopes for Kennedy and his dazzling fastball, the 1947 season did not begin promisingly for the southpaw.31 He didn’t make it into the third inning in either of his first two starts. However, Kennedy looked like he may be turning things around in his next start, a two-run complete-game victory over the Cardinals.

In May and June, Kennedy had one of his best periods as a major leaguer, pitching five complete-game victories in eight starts. After his last start in June, Kennedy had a 6-3 record and his ERA was a season-low 3.21.

Kennedy was injured on June 19 when he was knocked unconscious in batting practice by a line drive hit by Walker Cooper. He spent four days in Presbyterian Hospital, and there were concerns over the potential psychological impact of his injury.32 In his first appearance after returning from the disabled list, Kennedy surrendered six runs and didn’t make it out of the fourth inning. In his next start, he allowed four runs and didn’t retire a batter. Over the rest of the season, Kennedy never regained the form he had displayed in May and June, and he finished with a 9-12 record and a career-high 4.85 ERA. (His ERA drops to 4.35 if his first two starts after returning from the disabled list are excluded.)

Monty’s control problems continued, as he walked 28 more batters than he struck out in 1947. He walked more than he struck out in all but two of his major-league seasons. Kennedy also began to gain a reputation as a pitcher who couldn’t finish games.33 It was also suggested that sometimes Kennedy ran into problems by tipping his pitches; one article said he was “only learning the change-of-pace to go with his live fastball – he telegraphs the pitch.”34

However, Kennedy was optimistic in spring training in 1948. He felt he had improved control of his curveball, explaining, “Larry Jansen told me how to get my curve over the plate. … I was tipping it off before, too. He showed me how to hide it.” However, despite that optimism, Kennedy was sent to Triple-A Minneapolis on April 15.

On June 10 Kennedy threw a no-hitter for the Minneapolis Millers against Louisville, walking just three batters and striking out 10.35 He walked three and struck out 10, which included striking out the side in the ninth inning to ensure the no-hitter. It was the first no-hitter for Minneapolis in 33 years.36 Louisville batters only managed to hit five balls out of the infield.37 Kennedy repeatedly excelled against Louisville, throwing a two-hitter in his first start against the club, and taking a no-hitter into the seventh inning.38 He was recalled by the Giants on June 20.39 In 13 starts for Minneapolis, he had thrown five complete games and two shutouts. He posted a 3.81 ERA in 78 innings and struck out 77 batters.

The Amelia Beauty didn’t make it out of the fifth inning in his first start back in the majors. In that game, Bill Rigney threw away two straight double-play balls in the third inning.40 After suffering three straight defeats, Kennedy got his first victory with an abbreviated five-inning shutout.

Kennedy worked primarily out of the bullpen upon his return to the majors, but the Giants moved him to the starting rotation in August. New manager Leo Durocher said the move was made to determine if Kennedy could stake a claim to a rotation spot for the following season.41

Kennedy rose to the challenge and had a very impressive ending to the 1948 season. In his second start back in the rotation, he threw 11⅓ innings against the Cardinals and walked only two. He suffered the loss when Stan Musial hit a game-winning home run. Johnny Mize made two errors in the game, costing the Giants three unearned runs.

On September 1 Monty pitched his third straight complete game and posted nine strikeouts in a 3-1 victory against Pittsburgh. He lost his shutout to an unearned run in the ninth inning.42 Four days later Kennedy faced the Dodgers and went 11 innings again, surrendering only two runs. Another victory over the Pirates on September 13 concluded a stretch of six starts in which Kennedy threw five complete games, and went 11 innings in the sixth game.

After Kennedy lost a low-scoring affair, Durocher lamented, “It’s the same every time he pitches. We don’t get him any runs. … He hasn’t failed to pitch a good, strong game for us since he began starting.”43 In fact, the Giants won only four of the 16 games Kennedy started that year. He finished the season with a 3-9 record, which included seven complete games.

Assessing Durocher’s performance near the end of the year, one reporter commented, “The most meritorious feat of Durocher’s regime, however, was the launching of Monty Kennedy as an effective pitcher. Everybody in the Giant organization has had a whack at this brilliant but inexperienced lefty, trying to capitalize his natural talent. No one has succeeded. But it looks as if Leo has.”44

However, Kennedy was unable to replicate that improved performance in spring training the following year. After 10 spring innings, he had surrendered 10 runs and issued 18 walks. Nonetheless, Giants weren’t willing to give up on the talented hurler after the end to the previous season and there was hope that he would work well with Freddie Fitzsimmons, the club’s new pitching coach.

In May Kennedy shut out the Cardinals and Reds. In the Reds game he didn’t walk a batter, needed only 83 pitches, and allowed only two hits, both of which were seeing-eye singles.45 In a 16-0 win over the Dodgers at the Polo Grounds on July 3, Kennedy hit a grand slam off Morrie Martin; it was his only major-league home run.

Because he spent most the year in the rotation, Kennedy set career highs in most pitching categories, including wins (12), losses (14), starts (32), complete games (14), shutouts (4), innings pitched (223⅓), and strikeouts (95). He finished with a 3.43 ERA in 32 starts and six relief appearances.

In 1950 Kennedy began the year in the rotation, but was relegated to the bullpen for the last two months of the season. In 114⅓ innings, he posted a 4.72 ERA. He walked 53, hit three batters, and threw three wild pitches. His best starts during the season both came in shutout losses, a 2-0 game to the Cardinals and a 1-0 contest to the Reds.

Kennedy’s transition to a permanent role as a reliever continued during the 1951 season. He made 25 relief appearances and five starts. Kennedy posted a 1-2 record and a 2.25 ERA with 22 strikeouts and 31 walks in 68 innings.

After their miracle finish, the Giants faced the New York Yankees in the World Series. Kennedy made two relief appearances as the Giants lost the series in six games. In Game Four he pitched the top of the ninth inning and retired Yogi Berra on a pop fly and Joe DiMaggio and Gene Woodling on strikeouts. In Game Five, with the Giants already losing, Kennedy pitched two innings and surrendered a two-run homer to Phil Rizzuto in a 13-1 defeat.

By this point the club’s patience with Kennedy had begun to wear thin and one reporter summarized the situation by writing, “If Kennedy walked into any training camp with a mask on and started throwing, the manager would hand him a fountain pen as soon as he let go with two or three pitches, but when he removed the mask the skipper would wince. Not that Monty isn’t a handsome chap, but he’s a jinx.”46

Another reporter characterized the coming 1952 season as “make-or-break” for Kennedy.47 But pitching coach Frank Shellenback said the club would not give up on Kennedy. “You don’t give up on pitchers who can throw like him. You have got to hope and work that they come through. You can bet any scout he can go from Boston to San Diego, Minneapolis to Houston – crisscross the country – without finding a prospect who can throw like Kennedy. … Nobody lets a fellow like that go. Not for a long, long time.”48

Shellenback pointed to examples of pitchers who seemed to turn a corner after spending an extended period of time in the majors. “Sometimes it takes years, sometimes it comes overnight. [Whit] Wyatt was up and down and up and down again, before he delivered for Brooklyn with so little left to him. The Tigers stayed with [Carl] Hubbell for six years before quitting and then, practically overnight, Hubbell got the impulse to win. Wyatt and Hubbell had the stuff all the while. So does Kennedy.49

Kennedy began the 1952 season well, with 6⅓ innings of one-hit relief without issuing a walk and picked up the win. Seventeen days later, in his second start of the year, he threw a four-hit shutout against the Cardinals, issuing only one walk.50 He spent the first few months as a swingman for the Giants. On July 2, he pitched a strong complete game in a 2-1 loss to Boston’s Warren Spahn. This turned out to be Kennedy’s next to last start in the majors and, 10 days later, he was moved permanently to the bullpen.

Kennedy was fined $50 for throwing near Brooklyn batters in a game on September 8. When imposing the fine, NL President Warren C. Giles said, “It appears there was some degree of deliberate throwing at the batters on the part of Kennedy.”51

By the end of the season, Monty had finished his second strong year as a reliever. He posted a 3.02 ERA in 83⅓ innings and showed signs of improved control, walking only 31 and not throwing a wild pitch.

In 1953 Kennedy made the club out of spring training, but it was clear that his place on the staff was tenuous. One reporter commented, “Had the Amelia Beauty been given the benefit of two or three years in the minors before joining the Giants’ varsity, he might well have been one of the National League star pitchers.”52 In fact, Kennedy’s role on the staff was so uncertain that he was sent to the minors after making his first appearance of the year. He wound up splitting the year between New York and Minneapolis. He was recalled in June for four appearances, was returned to Minneapolis on July 12, then was recalled on July 27 and spent the rest of the season with the Giants.

Kennedy finished his season, and his major-league career, with a scoreless eighth inning at Wrigley Field against the Cubs in a blowout loss on September 12, 1953. During the season, he pitched only in Giants losses; the team didn’t win a single game of the 18 in which he appeared. He finished with a 7.15 ERA and walked 19 batters in 22⅔ innings.

Kennedy pitched in 249 major-league games, of which 127 were starts. He threw 48 complete games and seven shutouts. He won 42 games and lost 55 with a 3.84 ERA.

In 1954 Monty drifted through several minor-league and semipro teams. He pitched in one game for Minneapolis in the American Association and in four for the Richmond Virginians of the International League. After that season Kennedy never played professional or semipro baseball again. He had a positive year off the diamond; he married Jeanine Farnsworth, an airline hostess from Kansas City.53

Kennedy’s legacy appears to be that of a pitcher with a blazing fastball who never lived up to his potential. Years later, when discussing occasions when baseball clubs traded away players with tremendous potential that they never realized, a sportswriter remembered Monty, writing, “One case that immediately comes to mind is Monty Kennedy of the old New York Giants. He was a left-hander with an overpowering fastball that he could not control … and he never did deliver.”54

After retiring from baseball, Kennedy became a police officer in Richmond. He was promoted quickly to detective in 1960 and served on the force for over two decades, retiring in 1979.55 Kennedy didn’t leave baseball behind entirely; he played on the police team, which he later managed. His father, Garland, died in 1977, and his mother, Daisy, died the following year.

Monty Kennedy died in Midlothian, Virginia, on March 1, 1997. He was 64 years old and was survived by his wife, Jeanine, and three children, Monty C. Kennedy, Jr. and Pamela K. Bryant of Midlothian and Deborah K. Conner of Bettendorf, Iowa.56 He was predeceased by a daughter, Monica Lynn Hatsell.57 He was also survived by seven grandchildren and one great-grandson.58 Monty was also survived by five sisters – Hazel Bowman, Gladys McMillan, Josephine Harris, Mable Bartley, and Mollie Puryear.59 Kennedy is buried in Dale Memorial Park in Richmond.

Kennedy’s wife, Jeannine, died on August 2, 2001, and Deborah died at the age of 57 on July 15, 2012, after a battle with breast cancer.

This biography appears in “The Team That Time Won’t Forget: The 1951 New York Giants” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and C. Paul Rogers III.

Notes

1 Sometimes the name will appear spelled Monte. I have used the more common spelling, Monty, for consistency.

2 Joe King, “Ott Might Hit Jackpot with Monte Kennedy,” clipping dated March 29, 1946, in Kennedy’s file at the Baseball Hall of Fame with no indication as to source. (Joe King worked as a sportswriter for the New York World Telegram from 1931 to 1950.)

3 The information regarding Kennedy’s leaving high school is drawn from his Army enlisted papers.

4 Frank C. True, “Ott on Job as Press Agent,” clipping dated April 15, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file with no indication as to source. (Frank True was a sportswriter for the New York Sun who covered the Giants for many years.)

5 Ibid.

6 Ibid.

7 Frank C. True, “Giant Veterans See a Hubbell in Rookie Kennedy,” clipping dated April 9, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

8 Photograph from Binghamton Press, March 12, 1948, showing Kennedy with his 4-year-old daughter, Pat. There is no mention of Pat in his obituaries. Perhaps she is the same person as Pamela, who is mentioned as a child of Kennedy’s in his obituary.

9 Joe King, “Ott Might Hit Jackpot With Monte Kennedy,” clipping dated March 29, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

10 Ibid.

11 Joe King, “Ott Claims Giant Hitting Has Gone With the Wind,” clipping dated March 9, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

12 Joe King, “Ott Might Hit Jackpot with Monte Kennedy.”

13 Ibid.

14 Frank C. True, “Giant Veterans See a Hubbell in Rookie Kennedy.”

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid.

17 Joe King, “Rookie Giant Has the Speed of VanderMeer,” clipping dated April 9, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

18 Frank C. True, “Giant Veterans See a Hubbell in Rookie Kennedy.”

19 Frank C. True, “Ott on Job as Press Agent.”

20 Ibid.

21 Frank C. True, “Giant Veterans See a Hubbell in Rookie Kennedy.”

22 Frank C. True, “Giant Veterans See a Hubbell in Rookie Kennedy,” op. cit.

23 Joe King, “Giant Catchers High on Kennedy,” clipping dated May 6, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

24 Joe King, “Cellar Door Open to Listless Giants,” clipping dated April 26, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file. Kennedy got a no-decision in the game.

25 Joe King, “Giant Catchers High on Kennedy.”

26 Joe King, “Kennedy Among Best He’s Seen, States Diz Dean,” clipping dated June 4, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

27 Ibid.

28 Joe King, “Giants Hot Stuff With Top Clubs But Reds Make Them Play Dead,” clipping dated July 26, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

29 “Fine Job Done by Giant Rookie,” clipping dated September 13, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

30 Joe King, “Monte Gains Savvy in Shutout Job,” clipping dated August 23, 1946, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

31 Joe King, “Giant Pitching Picture Looks Rosy to Ott,” clipping dated May 13, 1947, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

32 “Monte Kennedy Skulled by Drive,” New York World-Telegram, June 19, 1947. Another account of the incident says that Kennedy lost consciousness after being struck by the line drive. See John Drebinger, “Kennedy Suffers Fractured Skull Before Pirates Trim Ottmen, 12-2,” New York Times, June 19, 1947.

33 Joe King, “Giants on Even Keel Because of Youngsters,” undated clipping in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file, July 17, 1947.

34 “Ballyhoo Clearing Way for Leo’s Return to Bums,” clipping dated August 13, 1947, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

35 Halsey Hall, “Hitless Game by Kennedy in Bandbox Park,” clipping from July 1948 in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file. (Halsey Hall was a sportswriter and broadcaster in Minneapolis.)

36 Ibid.

37 Halsey Hall, “Hitless Game by Kennedy in Bandbox Park,” Unidentified clipping, July 1948, Monty Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

38 Ibid.

39 Unidentified clipping in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

40 Joe King, “NL Contends Better Bell Big Cat Mize,” clipping dated June 1948 in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

41 Joe King, “Giants Hurlers Give Durocher the Horrors,” clipping dated August 1948 in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

42 “Kennedy Fans 9, and Barely Misses Whitewashing Bucs,” Unidentified clipping, September 2, 1948, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

43 “Kennedy Pitches and Pitches Well – And Still Can’t Win,” clipping dated, September 20 1948, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

44 Joe King, “Home Stand Finds Giants at Peak,” clipping dated September 9, 1948, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

45 Ed Sinclair, “Kennedy Pitches 2-Hitter,” clipping dated May 20, 1949, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

46 Ken Smith, “Kennedy, Perennial Giant Enigma, May Get Walking Papers,” clipping dated March 31, 1952, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

47 Joe King, “Club Ready to Profit on His Potential,” clipping dated March 6, 1952, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

48 Ibid.

49 Ibid.

50 Joe King, “Barber Strops His Razor for Braves’ Scalp, Bums’ Throat,” clipping dated May 23, 1952, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

51 “Giles Suspends Durocher Two Days and Kennedy $50 in Bean-Balling,” clipping dated September 10, 1952, in Hall of Fame file.

52 Jenifer L. Vancil, “Ex-Giants Pitcher Dead at 74,” Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 3, 1997.

53 “Kennedy to Wed,” clipping dated February 11, 1954, in Kennedy’s Hall of Fame file.

54 Arthur Daley, “Sports of the Times: The Wasted Years,” New York Times, December 10, 1969, 67.

55 Jenifer L. Vancil, “Ex-Giants Pitcher Dead at 74.”

56 Ibid.; “Monty C. Kennedy,” Obituary, Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 3, 1997.

57 Monty C. Kennedy obituary, Richmond Times-Dispatch, March 3, 1997.

58 Ibid.

59 Jenifer L. Vancil, “Ex-Giants Pitcher Dead at 74.”

Full Name

Montia Calvin Kennedy

Born

May 11, 1922 at Amelia, VA (USA)

Died

March 1, 1997 at Midlothian, VA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.