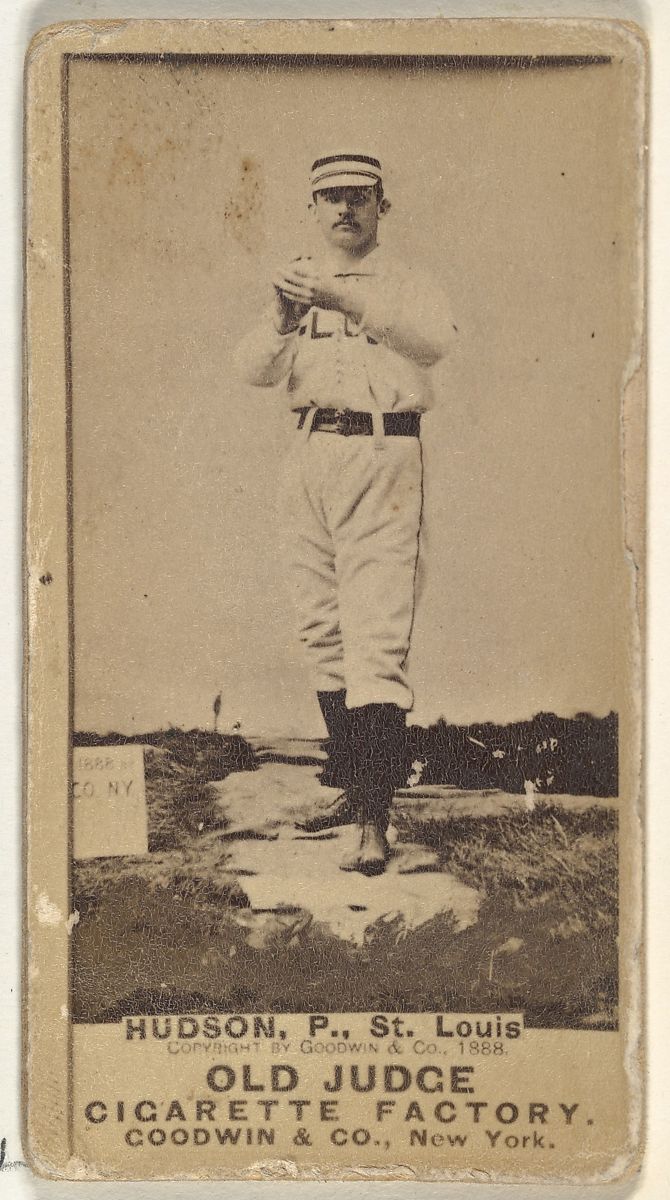

Nat Hudson

During the mid- to late 1880s, the St. Louis Browns dominated the major league American Association, capturing four consecutive pennants. Key to the club’s success was the standout pitching of Bob Caruthers and Dave Foutz, and thereafter, Silver King.1 Each of these right-handers was also a capable batsman who doubled as a Browns outfielder when needed. Bidding for a time to join this multi-talented trio was teammate Nat Hudson, another righty pitcher-outfielder. But arm and attitude problems, plus coming into a handsome inheritance, conspired to derail a promising career, and Hudson’s major league days were over before the decade was out. Upon leaving the game, he devoted himself to the lumber and home building industries, and dabbled in Republican Party politics of his hometown, Chicago. His life story follows.

During the mid- to late 1880s, the St. Louis Browns dominated the major league American Association, capturing four consecutive pennants. Key to the club’s success was the standout pitching of Bob Caruthers and Dave Foutz, and thereafter, Silver King.1 Each of these right-handers was also a capable batsman who doubled as a Browns outfielder when needed. Bidding for a time to join this multi-talented trio was teammate Nat Hudson, another righty pitcher-outfielder. But arm and attitude problems, plus coming into a handsome inheritance, conspired to derail a promising career, and Hudson’s major league days were over before the decade was out. Upon leaving the game, he devoted himself to the lumber and home building industries, and dabbled in Republican Party politics of his hometown, Chicago. His life story follows.

Notwithstanding his prominence in the baseball and political worlds of his day, reliable biographical data about Nathaniel P. Hudson are hard to come by. For more than 50 years, baseball reference works listed his date of birth as January 12, 1859.2 Today, Baseball-Reference, Retrosheet, and other authorities have Hudson born ten years later, on January 12, 1869. Neither birth date is historically sound. In all probability, Nat was born in north-side Chicago on an unknown date (perhaps January 12) in 1866 or 1867.3 He was the youngest of three children4 born to lumber yard clerk John A. Hudson (c. 1830-1887) and his wife Margaret (c. 1833-1887), both immigrants from the British Isles.5 Nothing is known of our subject’s early years except that he likely received the grade school education that was then the norm for the children of the urban working class.

Hudson, who stood 5-feet-9, was a lightly-framed right-handed batter and thrower. He began playing baseball in Chicago sandlots before graduating to the city’s fast amateur league. As a teenager, he attracted attention as a pitcher-infielder for the Chicago Blues, a highly regarded non-pro traveling nine.

Hudson entered the professional ranks in spring 1884, signing with an independent club based in Rock Island, Illinois. He made his pro debut in grand style, striking out 14 of his erstwhile Blues teammates and hitting a home run in a 12-4 pasting of his former club on April 19. A month later, he fanned 14 in a 16-3 Rock Island drubbing of the Peoria Reds of the minor Northwestern League.6

In mid-May, Hudson saw his first action against competition of major league caliber. He pitched creditably against the reserve nine of the St. Louis Browns but was undone by 11 Rock Island errors in a 9-2 defeat.7 A week later, he played third base during a 12-4 loss to the second-stringers of the National League’s Chicago White Stockings. Facing the less rigorous competition of a St. Louis semipro club on July 4, “Hudson made himself conspicuous for his brilliant playing, and in fact he was the center of attention. Walsh was out sick and Hudson played ‘short’ and to say he did well feebly expresses it,” declared the Rock Island Argus.8

Shortly thereafter, the financially strapped Rock Island club disbanded.9 Published reports then had Hudson joining Northwestern League teams in Grand Rapids, Michigan,10 and Terre Haute, Indiana.11 Whether he played for either club is unclear. Whatever the case, he finished the 1884 season with a NWL club in Quincy, Illinois, winning his only pitching decision.

Hudson began the 1885 season with the newly formed Keokuk (Iowa) Hawkeyes of the minor Western League.12 He lost three of four starts for his new club but posted a sparkling 1.32 ERA over 34 innings pitched before the Western League discontinued play on June 15. Weeks later, he hooked on with the Denver entry in the three-team Colorado State League. He started in the outfield; “exceeds any man thus far placed in right field” was the ambiguous newspaper description of his play.13 But eventually he made his way back to the pitcher’s box. In five starts, Hudson notched five complete-game victories for Denver.14

Under the direction of first baseman-manager Charlie Comiskey and spearheaded by the yeoman pitching of Bob Caruthers (40-13, with a league-leading 2.07 ERA in over 480 innings pitched) and Dave Foutz (33-14, with a 2.63 ERA in a shade over 400 frames), the St. Louis Browns went 79-33 (.705) and breezed to the 1885 American Association crown. The Browns then battled the National League champion Chicago White Stockings to a 3-3-1 draw in the World Series. During the ensuing winter, St. Louis club boss Chris Von der Ahe became disturbed by reports that staff ace Caruthers planned an extended vacation in Europe and might not return in time for the beginning of the 1886 baseball season.15 Lest his club start the campaign shorthanded in the pitching department, Von der Ahe signed young prospect Nat Hudson.16 A wire service dispatch hailed the acquisition, stating that Hudson “promises to be a wonder. He resembles [the formidable Charlie] Buffinton of the Bostons very much in style and effect, and has a very puzzling delivery. … [Hudson] has good judgment, and uses considerable strategy in his work.”17 It was also noted that the Browns’ new pitcher “comes from a family of standing in Chicago.”18

Nat Hudson officially became a major leaguer on April 18, 1886, when he pitched ninth-inning relief in a 10-3 St. Louis victory over Pittsburgh.19 He made his maiden start the following day, pitching “a fine game” but dropping a 6-5 decision to the Alleghenys.20 Days later he broke into the win column with a 15-9 triumph over the Louisville Colonels. Hudson then settled in as the Browns’ third starter, employed as needed behind stalwart frontliners Foutz (41-16) and Caruthers (30-14). The rookie filled the role admirably, posting a 16-10 record, with a 3.03 ERA in 234 1/3 innings. As expected of St. Louis hurlers, he also provided useful work as a backup outfielder-first baseman, posting a .233 batting average with 17 RBIs, overall. Meanwhile, the Browns (93-46, .669) cruised to another AA title.

The postseason brought a rematch between the Browns and the White Stockings. With the World Series knotted at two wins each, manager Comiskey passed over Foutz and Caruthers and sent young Nat Hudson to the box to pitch the pivotal Game Five. The youngster responded brilliantly, holding the Sox to three hits over seven innings in a darkness-shortened 10-3 St. Louis victory. After the game, umpire John Kelly was unstinting in his praise of Hudson. “I think he pitched in great style,” said Kelly. Hudson “is the best pitcher the Browns have got today, without a doubt. He will become one of the greatest in the business some day and it ain’t far off, either.”21 A day later, center fielder Curt Welch’s celebrated “$15,000 slide” across home plate in the bottom of the 10th made the Browns world champions.22

Great things were expected of Hudson in 1887, but the season – complete with contract hassles, trade rumors, family tragedy, and underperformance – turned out to be a bust for the pitcher. The death of his father in March gave Nat an early heartache. But the reported $50,000 inheritance that attended this sad event23 gave Hudson leverage in contract negotiations with club boss Von der Ahe. Hudson demanded a substantial raise over his $1,400 salary for 1886. Von der Ahe resisted. And soon the two were at loggerheads.24

While the contract dispute dragged on, the 1887 season began. Hudson, however, remained home, pitching for the Whitings of the Chicago City League.25 In time, Von der Ahe began shopping Hudson’s services to other clubs, but received no suitable offers for him.26 To fortify his pitching staff in Hudson’s absence, the St. Louis club boss made a purchase of his own, acquiring right-handed prospect Charles “Silver” King, late of the National League’s Kansas City Cowboys.27 The move proved a stroke of genius. King capably assumed Hudson’s place in the Browns rotation, and the club remained atop the American Association standings.

By late May, the holdout had lost its charm for Hudson. He now wrote Von der Ahe, ascribing “his protracted absence to his mother’s illness [Margaret Hudson had developed cancer], and to this cause alone.”28 He also disclaimed interest in playing elsewhere. “I was treated well in St. Louis, and have no reason to try and get away,” Hudson stated.29 Within days thereafter, Von der Ahe and his prodigal hurler reached agreement on a $2,500 salary and Hudson was back in the St. Louis fold.30

Hudson looked sharp upon his return, throwing a four-hit shutout against the Eastern League Newark Little Giants in an in-season exhibition game.31 But with newcomer Silver King doing sterling work in tandem with veterans Caruthers and Foutz, Browns field leader Comiskey had little need of additional pitching help. He managed to work Hudson into the rotation in June, but the returnee managed only two wins in six starts. Then in July, Hudson was obliged to return home as his mother’s condition worsened.32 He rejoined the club in time to split a pair of early August decisions, but soon thereafter he had to leave for home again.33 Nat remained at his mother’s bedside until her passing on August 31.34

Hudson did not return to St. Louis until early October and saw only sparing action as the 1887 season came to a close. But the Browns had not missed him. Behind the steadfast hurling of King (32-12), Caruthers (29-9), and Foutz (25-12), St Louis posted a 95-40-3 (.704) record and captured a third consecutive American Association title. For his part, Hudson went 4-4, with a substandard 4.97 ERA in a mere 67 innings pitched. He also played a handful of games in the Browns outfield and batted .250 (12-for-48) in 13 games, total. He saw no action in the ensuing 15-game marathon World Series between St. Louis and the NL champion Detroit Wolverines, won by the latter.

Despite his meager numbers and postseason inactivity, Hudson was reserved by the Browns for the ensuing season. But it was unclear whether Von der Ahe intended to retain him for the Browns or to designate Hudson for a St. Louis club that he intended to place in the minor Western Association for 1888.35 Shortly thereafter, however, Brooklyn’s acquisition of Bob Caruthers and Dave Foutz virtually assured Nat Hudson a place on the Browns’ roster for the 1888 season.

Slotted behind Silver King in the newly formulated rotation, Hudson got off to a whirlwind start, winning his first eight decisions. But as the campaign wore on, the workload took its toll on the slightly built hurler. To lessen the burden placed on Hudson during the pennant stretch, the Browns obtained Ice Box Chamberlain from Louisville. The acquisition paid immediate dividends, as Chamberlain won 11 games for St. Louis in the late going. With 25 games left on the schedule, Hudson made his final start of the season, notching a 15-5 victory over Baltimore on September 18. A relief appearance victory days later elevated his record for the season to 25-10, with a circuit-leading .714 winning percentage. Thereafter, he was assigned to center field, where his defensive work soon drew press raves. “Hudson carried off the fielding honors of the game,” observed the St. Louis Globe-Democrat following the Browns’ defeat of Brooklyn on September 29. “He seemed to be everywhere in center, and pulled down some hits that looked good for two or three bases.”36 Then, with another AA crown safely in hand for the Browns and a career-high 333 innings on his arm, Hudson left the club for a 10-day visit to the rejuvenating spas at Hot Springs, Arkansas.37

Once he returned to the club, Hudson was expected to complement King (45-20) and Chamberlain (11-2) in the postseason best-of-10 playoff against the National League champion New York Giants. And even if his pitching arm had not recovered, the wide-ranging Hudson afforded the Browns a significant defensive upgrade in center over gimpy-legged regular Harry Lyons. He was also a .255 batsman, vs. a mere .194 for Lyons. Yet as the World Series commenced at the Polo Grounds on October 16, Hudson was a no-show.

The Browns quickly fell behind the Giants, four victories to one, but frantic dispatches to Hot Springs and Chicago failed to stir the missing star. Finally, as the Series action shifted to St. Louis, Von der Ahe received the following wire message: “Dear Sir: I received your telegram and am very sorry to say that I cannot meet the club at St. Louis. I am in no condition to play after bathing so much. It would take me ten days to get into condition. Hoping you will excuse me, I am respectfully yours, Nat Hudson.”38

With King and Chamberlain overworked and stationary center fielder Lyons going a feeble 2-for-17 at the plate, the Browns proved no match for New York. The Series outcome was decided in the Giants’ favor after only eight games.39 Yet notwithstanding his abandonment of the club at World Series time, Hudson was reserved by the Browns for the 1889 season.40 Indeed, his salary was reportedly raised to $3,000.41 Still, Von der Ahe, Comiskey, and the others never really forgave him. Hudson’s days with the club were numbered.

The Browns got off smartly in 1889, winning their first six games behind King and Chamberlain. But Hudson was battered in game seven, dropping a lopsided 17-7 verdict to Louisville. Six weeks later, he got a second start and prevailed over Columbus, 9-3. On June 27, Hudson was lifted after going seven innings against Cincinnati, complaining of a sore arm. The 8-6 defeat dropped his record to 3-2. Days later, he was “suspended without pay for 30 days for insubordination.”42 Upon his arrival home in Chicago, Hudson contacted club boss Von der Ahe and asked that his suspension be lifted. When Von der Ahe refused, Hudson threated to institute a $10,000 lawsuit.”43 The threat proved an idle one.

In mid-July, Von der Ahe attempted to divest himself of the inactive Hudson by trading him to Louisville for hard-throwing, hard-drinking Toad Ramsey.44 The swap was well received in Louisville, the Courier-Journal informing readers that “Hudson will make a valuable man for the Louisville club. He is a sober, conscientious young man, who plays ball to win. Besides being a good pitcher, he can play almost any position on the field. He is a first-class outfielder and there are few players who can play the initial bag better than he. Hudson is a handy man with the stick, and his good batting has helped the Browns to many a victory.”45 Hudson, however, was not disposed to play for Louisville and refused to report.46 Weeks thereafter, a $1,000 payment to Louisville by the Minneapolis Millers of the Western Association secured Hudson’s release and brought his major league career to a close.47

In 125 Browns games spread over four seasons, Hudson logged an eye-opening 48-26 (.649) record as a pitcher, posting a 3.08 ERA in 694 1/3 innings. He struck out 258, walked 156, and held enemy batsmen to a .253 batting average. The versatile Hudson also provided first-rate barehanded defense in 86 games in the box (.924 fielding percentage), 40 games as an outfielder (.896), and nine at first base (1.000). And he helped the Browns with the bat, hitting a useful .247, with 56 runs scored and 58 RBIs.

Hudson was agreeable to playing for Minneapolis and proved a valuable addition to the club. He went 7-2 in 10 starts, and manned right field in 22 other contests, batting a robust (46-for-129) .357 with 20 extra-base hits for the Millers. To no surprise, he was placed on the Minneapolis reserved list as the season neared an end.48

In 1890, the arrival of the newly formed Players League expanded the number of major league clubs with roster spots to fill to 24. Yet no interest was expressed in the services of the still-young Hudson. His only recourse was to return to Minneapolis. There were, however, some changes that he could effect. The most significant of these was his marital status. Shortly before the season began, he took 24-year-old fellow Chicagoan Anna Stark as his bride. The couple remained united until Anna’s death some 25 years later, but their union yielded no offspring.

Although intermittently plagued by arm miseries, Hudson again pitched well for Minneapolis. By early July, he had won 16 of 21 starts and led Western Association hurlers in winning percentage (.763).49 But in a salary dump, Hudson was among the Millers jettisoned by the cash-strapped club.50 Once home in Chicago, the abruptly unemployed hurler was reportedly the recipient of contract offers from various major league clubs.51 But the financially independent Hudson was “not anxious to sign for a while yet. He prefers to remain idle for a while.”52 For the remainder of the year, he amused himself by taking in games of the Chicago Players League club run by Charlie Comiskey53 and pitching occasionally for a semipro club in Houghton, Michigan.54

Spring 1891 produced published reports that Hudson might return to the St. Louis Browns.55 He was also named in connection with an independent pro club in Aurora, Illinois.56 But with his pitching arm now chronically aching, Hudson focused on his business interests, concentrated in the lumber and building industries. For the next several summers, he confined his ball playing to weekends in the Chicago City League.

In 1897, increasing involvement in Chicago Republican Party politics led to Hudson’s appointment as clerk of the city election commission. A decade later, he actively campaigned for Republican mayoral candidate Fred A. Busse, a childhood friend.57 In time, Busse’s election led to Hudson’s elevation to the post of election commissioner.58 Shortly thereafter, scandal erupted when a foundry company established by Mayor Busse, Hudson, and a political ally was accused of siphoning off money designated for city building projects.59 Whether scandal-connected or not,60 Hudson was subsequently relieved of his duties on the election commission.61

In March 1915, the death of Anna Hudson left our subject a widower. Thereafter, he spent the remainder of his life out of the public spotlight, working in the collection department of the Commonwealth Edison Company.62 Sometime in the early 1920s, Hudson remarried, taking Eleanor Cole Brown, a divorcée with two teenage sons, as his second wife.

On March 14, 1928, Nathaniel P. Hudson suffered a heart attack and died in his Chicago residence. He was about 62.63 Following funeral services, his remains were interred in the Hudson family plot in Rosehill Cemetery, Chicago. He was survived by Eleanor and stepsons Dwight and William.64

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

Sources for the biographical information imparted above include the Nat Hudson profiles published in the New York Clipper, March 26, 1887, and Major League Player Profiles, 1871-1900, Volume 1, David Nemec, ed. (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2011); US Census reports accessed via Ancestry.com; and certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Caruthers posted a 218-99 (.688) record, with a .282 BA in his 10-season major league career. Foutz went 147-66 (.690) before arm miseries hastened his conversion to full-time outfield-first base duty. He hit .276 lifetime, with two 100+ RBI seasons. King logged a 203-152 (.572) record but was not the batsman that Caruthers and Foutz were.

2 Reference works from the first edition of the Turkin & Thompson baseball encyclopedia (1951) through the seventh edition of Total Baseball (2001) list Hudson’s date of birth as January 12, 1859. This DOB is likely derived from Hudson’s TSN player contract card.

3 Based on US Census Reports for 1860, 1870, and 1880.

4 Nat’s older siblings were Rebecca (born 1860) and Eliza (Jennie, 1864).

5 Census reports variously list John Hudson as being born in England, Scotland, or Ireland, while wife Margaret is uniformly listed as an Irish immigrant.

6 Per the Davenport (Iowa) Sunday Democrat, May 11, 1884: 4.

7 See “Rock Island: Base Ball at St. Louis,” Davenport Democrat, May 19, 1884: 4.

8 “The Green Diamond,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, July 5, 1884: 5.

9 “Diamond Briefs,” Davenport (Iowa) Gazette, July 9, 1884: 3.

10 Same as above.

11 Per “On the Diamond,” Rock Island Argus, July 10, 1884: 5.

12 Hudson’s signing with Keokuk was reported in “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 1, 1885: 3. Keokuk assumed the Western League place of the just disbanded Omaha Omahogs.

13 “Between the Bases,” (Denver) Rocky Mountain News, July 12, 1885: 3.

14 Baseball-Reference also has Hudson throwing a complete game victory for Colorado State League rival Leadville, but no evidence that Hudson pitched for Leadville was discovered by the writer.

15 Caruthers’ purported travel plans were reported in “Sporting Notes,” Wheeling (West Virginia) Register, February 28, 1886: 2; “The Sporting World,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 16, 1886: 5; and elsewhere. As it turned out, Caruthers remained home in Memphis, but the episode nevertheless garnered him a healthy salary increase from club owner Von der Ahe and a new nickname: Parisian Bob.

16 See “Sporting Notes,” Omaha World-Herald, March 19, 1886: 2; “Sporting Notes,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 15, 1886: 1. Also working in Hudson’s favor were his decent showing against the Browns reserves in 1884 and the fact that he and Browns field leader Comiskey were from the same north Chicago neighborhood.

17 Disseminated in “Base Ball Gossip,” New York Sun, March 7, 1886: 11; “Base Ball Brieflets,” Boston Herald, February 28, 1886: 2; and elsewhere.

18 Same as above.

19 Per the box score/game account published in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 19, 1886: 6. Hudson came on in relief of Dave Foutz and was charged with two unearned runs while striking out two in his inning of work.

20 “Sporting: Pittsburg, 6; St. Louis, 5,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 20, 1886: 4.

21 “It Beats the Old Style,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 23, 1886: 8.

22 The celebrated Welch slide may well have been apocryphal. See Bob Tiemann, “Curt Welch’s Winning Slide,” in Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the Nineteenth Century, Bill Felber, ed. (Phoenix: SABR, 2013), 184-186. Whatever the case, St. Louis club owner Von der Ahe split the World Series pot with his players, with each of the Browns getting about $575.

23 As reported in “Brieflets,” Rock Island Argus, March 24, 1887: 7. Later reports greatly inflated the Hudson inheritance. See e.g., “General Sporting Notes,” Pittsburg Press, September 1, 1890: 5: ($80,000). How father John A. Hudson, listed as a lumberyard worker in the 1880 US Census, became a man of such substantial wealth is unknown, but reports that he left a sizable bequest to son Nat were borne out by subsequent events.

24 For a pro-Von der Ahe take on the contract squabble, see Eli, “Nat Hudson’s Great Gall,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1887: 1.

25 As reported in “Diamond Dust,” Chicago Inter Ocean, March 27, 1887: 7. See also, “The Hudson Muddle,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 29, 1887: 6. American Association secretary Wheeler C. Wyckoff soon circulated an official notice reminding Whitings opponents that the National Agreement bound Hudson to the St. Louis Browns and banning clubs in Organized Baseball from taking the field against him.

26 See “Nat Hudson Now for Sale,” The Sporting News, May 21, 1887: 1. Cincinnati and Louisville were among the AA clubs who declined to purchase the Hudson contract.

27 As reported in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 5, 1887: 8.

28 “Nat Hudson Wants to Play in St. Louis,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 25, 1887: 3.

29 Same as above.

30 Per “St. Louis Gets Hudson,” Baltimore Sun, May 27, 1887: S2; “Hudson Signs – Will He Be Sold?” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 27, 1887: 6.

31 As reported in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, June 1, 1887: 8.

32 Per “Base Ball Gossip,” Cleveland Leader and Herald, July 17, 1887: 15.

33 See Hudson Leaves for Home,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 9, 1887: 3.

34 Per State of Illinois death records accessed via Ancestry.com. See also, “Brieflets,” Rock Island Argus, September 5, 1887: 4; “Diamond Notes,” Cleveland Leader and Herald, September 3, 1887: 3; “Nat Hudson’s Mother Dead,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 1, 1887: 8

35 As reported in Sporting Life, November 9, 1887: 3.

36 “Browns 7, Brooklyn 4,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, September 30, 1888: 10. Hudson’s fielding was also complimented in “Just What Is Wanted,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, September 30, 1888: 16.

37 See “Nat Hudson Takes a Rest,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 1, 1888: 6.

38 “Nat Hudson Will Not Play,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 27, 1888: 5.

39 The clubs played the final two Series games as scheduled, with the Browns winning both meaningless contests before miniscule crowds.

40 Per “The Reserved Players,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 18, 1888: 8.

41 “Base Ball Briefs,” Cleveland Leader and Herald, January 22, 1889: 3.

42 “Pitcher Hudson Suspended,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 2, 1889: 8. See also, “Suspension of Hudson,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 2, 1889: 8.

43 According to Joe Pritchard, “St. Louis Siftings,” Sporting Life, July 17, 1889: 2.

44 See “Ramsey Exchanged for Hudson,” (Louisville) Courier-Journal, July 18, 1889: 6; “Hudson Exchanged for Ramsey,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 18, 1889: 8.

45 “Ramsey Exchanged for Hudson,” above.

46 St. Louis, however, retained the rights to Ramsey regardless of whether or not Hudson reported to Louisville. See “Will Louisville Get Hudson?” Courier Journal, July 29, 1889: 2; and “How St. Louis Secured Ramsey,” Courier-Journal, July 27, 1889: 6

47 As reported in the Minneapolis Tribune, August 18, 1889: 11; St. Louis Republic, August 17, 1889: 14; and elsewhere.

48 See “The Reserve List,” Minneapolis Tribune, September 15, 1889: 2.

49 As reported in “Minneapolis News: The Release of Hudson and Myers,” Sporting Life, July 26, 1890: 1; “Hear the Cranks Howl!” Minneapolis Times, July 16, 1890: 4; and elsewhere. Another source places the Hudson record at 13-4, with a Western Association-best .763 winning percentage. See The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 3d ed. 2007), 158.

50 Hudson’s high $400 per month salary was cited as the reason for his release. See “Base Ball Notes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 17, 1890: 5; “Released by Minneapolis,” Omaha World-Herald, July 16, 1890: 2.

51 See e.g., “Base Ball Notes,” Pittsburg Dispatch, August 5, 1890: 7; “Diamond Gossip,” Omaha World-Herald, August 3, 1890: 5; “Notes of the Diamond,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 24, 1890: 24

52 According to the Chicago Tribune, August 6, 1890: 6.

53 See “Notes and Gossip,” Sporting Life, August 2, 1890: 4

54 As reported in the Minneapolis Times, October 12, 1890: 3.

55 “Baseball Briefs,” Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, March 1, 1891: 16.

56 “Baseball Notes,” Chicago Tribune, May 10, 1891: 4.

57 See “Ball Players for Busse,” Chicago Inter Ocean, March 26, 1907: 3. Joining Hudson in support of the Busse candidacy was an even bigger name in Chicago baseball circles: former star infielder Fred Pfeffer.

58 Per “Changes in Election Board,” Chicago Tribune, April 29, 1909: 2.

59 See “Outrageous Overcharges on Sale of Castings to City by T.A. Cummings Foundry Company Proved by Documents – Market Prices of Iron Show Huge Graft,” Chicago Inter Ocean, November 16, 1909: 1; “More Money Stolen from City; $40,000 Given to Cummings,” Chicago Inter Ocean, November 14, 1909: 3.

60 Mayor Busse, Hudson’s political patron, lost a mayoral reelection bid in 1911.

61 As reported in the Chicago Tribune, December 8, 1910: 11. Hudson subsequently filed suit to regain his election commission position but lost a drawn-out court battle. See “Loses Fight to Stay on Election Board,” Chicago Inter Ocean, May 16, 1912: 2.

62 Per Bill Lee, The Baseball Necrology (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 191, and the 1920 US Census.

63 A brief Associated Press obituary mistakenly reported the deceased’s age as 59. See e.g., “Nathaniel Hudson Dies; Pitched for Local Pastimes,” Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, March 15, 1928: 15; “Nat Hudson Dead,” San Antonio Light, March 15, 1928: 12.

64 Per State of Illinois death records and the Nathaniel P. Hudson death notice published in the Chicago Daily News, March 16, 1928: 42.

Full Name

Nathaniel P. Hudson

Born

January 12, 1867 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

March 14, 1928 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.