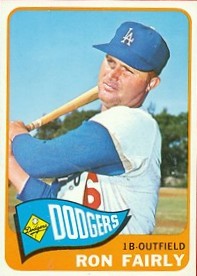

Ron Fairly

Ron Fairly was born to be a major leaguer on July 12, 1938. His father Carl had a 10-year minor league career and reached the International League with Toronto and the American Association with Indianapolis. The year Ron was born was one of Carl’s best seasons as he hit .302 and slugged .406 for the Class B Macon Peaches.

Ron Fairly was born to be a major leaguer on July 12, 1938. His father Carl had a 10-year minor league career and reached the International League with Toronto and the American Association with Indianapolis. The year Ron was born was one of Carl’s best seasons as he hit .302 and slugged .406 for the Class B Macon Peaches.

“Like any dad he played with his sons,” said Ron Fairly in an interview with this author in November of 2012. “We played catch; he gave me all the fundamentals and helped make me a ballplayer.” Carl even took home movies of Ron’s games and used them as a training tool. Ron’s brother Rusty, about five years older than Ron, was also an excellent athlete. He was an All American quarterback at the University of Denver and played in the Canadian Football League before injuries led to a career in coaching.

After Carl’s professional baseball career ended he became a dispatcher and delivery manager for 300 stores in the Thrifty Drug Store chain in Southern California. “He was responsible for the trucks getting food and soda fountain products to all the stores,” Ron remembered. Carl’s wife Marjorie raised their two sons and worked part-time at the May Company department store selling draperies.

Ron moved to Southern California at three months old when the Peaches season ended and was raised there. He played basketball and baseball (pitcher and centerfield) at Long Beach Jordan High School. His basketball play was good enough that John Wooden offered Fairly a full basketball scholarship at UCLA. “I averaged 18 points a game in high school,” Fairly remembered.

Before he actually made it to Westwood, Fairly’s father suggested he check out USC and legendary baseball coach Rod Dedeaux. The left-handed Fairly, “took one look at the short right field fence at Bovard Field (the baseball home of the Trojans at the time) and compared it to the open field at UCLA, and pretty much changed my mind right there. Dedeaux’s personality was a lot better than (Bruin baseball coach) Art Reichel’s, too.”

Fairly played freshman basketball at USC in the fall of 1956, but practices interfered with the baseball training table. Fairly also recognized that he would have trouble starting for the Trojan basketball team and decided to focus on baseball. “Baseball was clearly my best sport,” Fairly said.

Fairly was the varsity centerfielder for USC when it won the College World Series in 1958. Scouts had been following him since ninth grade, and by 1958 the offers became too large to ignore. “I could have signed with any team I wanted,” Fairly said. The White Sox offer of $100,000 was the largest, he said, but the organization would not verify that offer to Fairly’s dad. The Yankees also made a significant offer, but it was the Dodgers’ offer of $75,000 through scout Harold “Lefty” Phillips, plus the chance for Fairly to play at home in Southern California that won his signature. “I definitely took less to stay close to home,” he said.

There was no rule in 1958 mandating big league service time for bonus babies, so Fairly’s rapid ascent to Los Angeles was on merit. In 69 games split between Des Moines in the Class A Western League and St. Paul in the Triple-A American Association, Fairly hit .297 with 14 homers and a .528 slugging percentage. He arrived in Los Angeles in early September and continued his hot hitting while getting playing time for a team destined to finish in seventh place and perhaps planning an overhaul. Facing National League pitching, Fairly hit .283 in 53 at bats with two homers. In a period covering less than four months, Fairly won the College World Series, signed a $75,000 bonus contract, succeeded in the minors and was introduced to the Big Leagues. Hall of Famer Robin Roberts surrendered Fairly’s first big league hit in his second game on September 10 at Connie Mack Stadium. It was a single to right. A few minutes later Fairly scored his first run on Frank Howard’s first major league home run. Two days after that Fairly hit his first homer off Ron Kline at Forbes Field.

Upon his arrival, Fairly asked manager Walter Alston where he should work out and Alston sent him to right field. There to meet him, and at first none too cheerfully, was incumbent Carl Furillo. “Carl’s greeting to me was, ‘I’m the right fielder on this team. You can have it when I’m finished and I’m not finished yet.’” Furillo was in the midst of his last good season as one of the few Brooklyn Dodgers who adjusted well to the West Coast in 1958. His .290/.343/.482 slash line was good for an .825 OPS and earned him 23rd place in the NL MVP voting.

Once Furillo got to know Fairly a bit better and realized that the youngster did not behave like a threat to the veteran’s position, he took Fairly under his wing and showed him the nuances of playing rightfield in the National League. “Carl showed me how to play to corrugated wall at Connie Mack Stadium and the nuances of rightfield in the other ballparks. He would also tell me what to expect from the opposing pitchers. I always appreciated the fact that he did that,” Fairly said. After Furillo was released in 1960 Fairly took Furillo’s number six as a tribute to his mentor. Furillo biographer Ted Reed wrote that Furillo was at first offended to see his number on Fairly’s back, but one of his old roommates, Sandy Koufax, called Furillo and assured him that Fairly meant wearing the number as a way to honor Furillo’s contribution to the beginning of Fairly’s career.

Fairly’s initiation into the big leagues was enhanced by where he was and with whom he played. “I had a chance to play with the Brooklyn guys: Furillo; Duke Snider; Carl Erskine; Clem Labine; Gil Hodges and Junior Gilliam. People today don’t realize how damn good those guys were both on and off the field. When we were in a city like Chicago, New York or San Francisco we would wear a coat and tie to the ballpark and then go out together after the game to a very nice restaurant where we would have a couple of cocktails, enjoy a fine meal and talk about the game. Those guys taught me that wherever we went there will be somebody who would recognize us and we had to look like big leaguers and conduct ourselves accordingly.”

Fairly’s fairy tale-like baseball career continued in early 1959. As late as June 4 his batting average was over .300 and he was getting regular playing time on a team that was surprisingly challenging for first place. However, a 1-30 run through the rest of June knocked Fairly’s average below .250 and its owner out of the starting lineup. According to the Ron Fairly version of a team publication called “The New 1961 Dodger Family” which is a series of pamphlets on each player, team Vice President Fresco Thompson counseled Fairly that he was committing himself too soon at the plate. Soon, the publication asserts, “opposing hurlers got wise to this eager beaverism and began throwing him nothing but junk…”

Fairly partially backs that assessment, but adds to it. “I was young and the pitchers figured out how to pitch to me. At the same time Furillo’s calf healed and (Duke) Snider recovered from water on the knee and I began playing less regularly which made it difficult to come out of my lull.” Outfielders Don Demeter, Wally Moon, and Norm Larker also played well for Los Angeles and cut into Fairly’s playing time in 1959.

Still, Fairly remained on the big club all season, appearing in 118 regular season games and all six games of the Dodgers’ triumph in the 1959 World Series. He had three at bats in those six games and no hits. But, he was a World Champion in his second professional season one year after his College World Series triumph. Winning for Fairly then was almost a given. “My teams did well every place I played. To that point I had been on winning teams nearly my entire life,” he said.

A stint in the Army Reserves contributed to the first major interruption in Fairly’s string of athletic success. “I had three days off after we won the World Series, and then spent six months in the Army. Spring training for me was one day. The Dodgers sent me to Spokane in 1960 to play myself into shape.” And while playing himself into shape, Fairly tore through the Pacific Coast League. In 153 games for the Indians Fairly had an OPS of .965, hit 27 homers, coaxed 100 walks and drove in 100 runs. He was clearly ready to compete for a big league job in Los Angeles.

“You had to be on top of your game to stay on the Dodgers in those days,” Fairly remembered. “My year in Spokane let the ballclub know I was a pretty good player. Not everyone remembers that we had three AAA clubs then and all three teams were good.” Though Furillo was gone and Demeter was traded on May 4, Fairly still had to compete with Snider, Moon, Larker, Howard, Tommy Davis, and Willie Davis for playing time in the 1961 Los Angeles outfield. Despite a poor hitting spring Fairly made the club, but was relegated to pinch hitting duties for April. He played some in right field in May and hit well. But his big break came at an unfamiliar position in June.

“Gil (Hodges) didn’t like to take infield, so Norm Larker and I would each take a round of infield at first base every day. By June Gil had a bad thumb and could barely grip the bat. Alston asked me if I could play first and I said yeah, and then he told me ‘you’re playing there today.’

“Roger Craig was our pitcher that day (June 12 in San Francisco) and he told me not to worry about anything. There weren’t any tough plays that day or the next few days I was out there. It was probably five games before I had a ground ball hit to me and I made that play. Pretty soon management decided I could play first base, which opened up new opportunities.”

First base became Fairly’s primary position until Wes Parker established himself in 1965 and Fairly went back to rightfield because, according to both Fairly and Parker, Fairly had the better arm. Fairly says he finally realized he was likely to stay in Los Angeles after the 1962 season, which was the first year he had over 500 at bats. Those at bats might not have come at the expense of Moon, Snider, Howard or the Davis boys if Fairly had remained strictly an outfielder. Learning first base also gave him a position to play in the 1970s as he aged. For his career he played over 1000 games each at first base and in the outfield.

From 1962-1966 the Dodgers might have been major league baseball’s most dominant team. The team won three pennants, tied for first place another year before losing in a playoff, and won two World Series, including a sweep of the Yankees in 1963. Amidst all that winning the team had two MVPs (Maury Wills and Koufax) and four Cy Young Award winners (Don Drysdale once and Koufax three times). “We had really good pitching, and a bunch of .280 and .290 hitters who didn’t strikeout much. We didn’t have to score a lot of runs because nobody scored a lot of runs in Dodger Stadium. Since then they’ve moved the fences in 15 feet and that makes a world of difference. We also had good speed and played good defense, which a lot of people don’t recognize. We went into every game expecting to win.”

The blight on that team’s record is the collapse in the last week of the 1962 season and the waste of a two run lead in the ninth inning of the deciding playoff game that season against the Giants. “First of all we didn’t have Sandy for the second half of 1962. Do you think he would have won an extra game or two for us?” Fairly asked rhetorically. “Even with all that, if (Coach Leo) Durocher doesn’t move (second baseman Larry) Burright into the hole the ground ball (Harvey) Kuenn hits (in that ninth inning) to (shortstop) Wills is a double play instead of a force and we have two outs and nobody on.” Fairly was in rightfield and says he saw Durocher move the second baseman out of double play position. San Francisco scored four runs in the top of the ninth that day as the Dodgers turned a 4-2 lead into a 6-4 loss.

The other memorable pivotal moment was the decision Alston had to make regarding his game seven starter in the 1965 World Series. His choice was between Koufax on two days rest or Drysdale on three. “We didn’t care who started. We had two Hall of Fame pitchers and really couldn’t lose either way,” said Fairly. “I think Alston chose Koufax because Sandy was more muscular than Don and took longer to warm up. If Drysdale got in trouble it might take Sandy too long to get ready, but if Sandy started warm-up times would not be an issue.” As it turned out relief wasn’t necessary as Koufax went the distance and struck out 10 in a 2-0 win for the Dodgers.

Through this period of Dodger domination Fairly was a consistent contributor regardless of where he played. His OPS in what is now known as the second dead ball era ranged from .734 to .844. His On Base Percentage ranged from .347 to .380, and his WAR hovered between 1.7 and 3.1. Yet at age 28 and 29, in 1967 and 1968, it appeared that Fairly’s career suddenly fell off a cliff.

His OPS fell to around .600 and his WAR dropped below zero. At a time when most hitters are at their peak, Fairly had suddenly and seemingly inexplicably turned into one of the least effective regulars in the major leagues. What happened, he says, was simple.

“After Sandy retired (in November of 1966) Drysdale told (General Manager) Buzzie (Bavasi) that we should lengthen the grass and slow down the infield,” Fairly remembered. “I thought that was crazy. We were a ground ball/line drive team. We didn’t hit the ball in the air. Well, Buzzie lengthened the grass and it killed me. I didn’t have the speed to beat out infield hits and ground balls that had been getting through for me were winding up in infielders’ gloves.”

The culmination of what seemed to be Fairly’s decline came on June 11, 1969, when he was traded to Montreal with Paul Popovich for Wills (who had been traded to Pittsburgh in 1966 and went to Montreal in the 1969 expansion draft) and Manny Mota. His career was almost immediately resurrected. His OPS again hovered near or above .800 for the next five seasons, .821 for the period, and he turned into a year-in-and-year-out 3 WAR player for the Expos. He became an All Star for the first time in 1973 and his time in Montreal helped add another decade to his career. Yet, Fairly hated the trade and what it meant.

“I hated it. I didn’t like any part of it,” Fairly declared emphatically. “I hated the weather and I hated playing for a last place team. In 1970 our stated goal was to win 70 in ’70. In other words, we were playing not to lose 100 games and would be happy losing 90 games. With the Dodgers I went into every game expecting to win, even when we were down in 1967 and 1968. That couldn’t be the case in Montreal. When I showed my four-year-old son, Mike, where I would be playing (on a map) after the trade he looked at me sadly and asked, ‘Does this mean I don’t have a daddy anymore?’”

But Fairly persevered and even thrived. “I was a major league player paid to perform as well as I could play. I was still getting a check, and I still had the hope that some other team would come and get me.”

It took more than five years, but on December 6, 1974, the St. Louis Cardinals rescued Fairly from his Canadian purgatory in a deal that netted Montreal two minor leaguers. In St. Louis Fairly became an effective part-time player. He hit .301 in 1975 and gave the Cardinals about two games of WAR in his 180 games with them over two seasons. He then played 15 games with Oakland for the 1976 stretch drive as the A’s failed in an attempt to win the AL West title for a sixth straight season. Charley Finley sold Fairly’s contract to Toronto for the 1977 season, during which Fairly became the only player to appear in All Star Games for both Canadian franchises. He finished up with the Angels in 1978 when a season similar to those he suffered in 1967 and 1968 with the Dodgers finally ended his time as a player at 40. His career in baseball, though, still had nearly 30 years to run.

Just before spring training in 1979 Gene Autry, in the unusual position of owning the ball club and the television station, offered Fairly a three year contract to be the sports anchor on KTLA and work 35 Angels TV games with Dick Enberg and Drysdale, his old friend from the Dodgers. “I had a year left on my playing contract, but a three year broadcasting deal, even with the pay cut, seemed like the better opportunity at that stage,” Fairly said.

Fairly worked for the Angels until 1987 when he moved to San Francisco to replace Hank Greenwald as the Voice of the Giants. Though by then he was a competent announcer, Fairly proved to be unpopular with Giants fans. “I took over for Hank Greenwald, that was strike one. I was from Southern California, which was strike two. And I was a Dodger, which was strike three.” Greenwald returned after two years and according to Fairly they worked well together and “had a lot of laughs” until 1993 when the ex-Dodger moved further up the coast to Seattle to call Mariners games. He retired from broadcasting in 2006 at 68, though he filled in for about a third of the 2011 season for the Mariners after Ford C. Frick Award winner Dave Niehaus died suddenly after the 2010 season.

In retirement, Fairly played golf, stayed around the house, and “enjoy[ed] the weather in Palm Desert.” He and his wife Mary had three sons, Mike, Steve and Patrick, plus seven grandchildren.

Fairly died after a long battle with cancer at the age of 81 on October 30, 2019.

Sources

Interview with Ron Fairly, November 26, 2012

Los Angeles Dodgers Yearbooks, 1959-1969

The New 1961 Dodger Family, Ron Fairly

Greenwald, Hank “This Copyrighted Broadcast,” © 1999 Woodford Publishing

Reed, Ted “Carl Furillo, Brooklyn Dodgers All Star,” © 2011 McFarland & Company

Full Name

Ronald Ray Fairly

Born

July 12, 1938 at Macon, GA (USA)

Died

October 30, 2019 at Palm Desert, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.