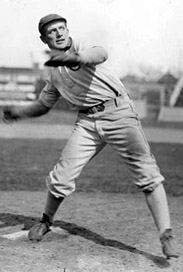

Roy Patterson

Pitcher Roy Patterson is best remembered for throwing the first pitch (and recording the first win) in American League history. The 24-year-old right-hander, who would soon become known as the “Boy Wonder,” took the mound at Chicago’s South Side Park on April 24, 1901. Nearly 10,000 fans saw Patterson and the Chicago White Stockings defeat the Cleveland Blues, 8-2. Patterson’s firsts were made possible only because the other three American League games scheduled that day were rained out.

Pitcher Roy Patterson is best remembered for throwing the first pitch (and recording the first win) in American League history. The 24-year-old right-hander, who would soon become known as the “Boy Wonder,” took the mound at Chicago’s South Side Park on April 24, 1901. Nearly 10,000 fans saw Patterson and the Chicago White Stockings defeat the Cleveland Blues, 8-2. Patterson’s firsts were made possible only because the other three American League games scheduled that day were rained out.

Patterson had a rather modest career mark of 81 wins and 72 losses in seven major-league seasons (1901-1907), but his record was deeply affected by nagging arm injuries and poor run support from his White Sox teammates. His career ERA of 2.75 was very respectable, even for the Deadball Era. The 6-foot, 185-pound, blond-haired (he was of Scandinavian ancestry) Patterson was described as “cool, quick-witted, and overall a gentleman, perfect in behavior and absolutely no trouble.” i He was similar in demeanor to a contemporary in the National League, Christy Mathewson.

Roy Lewis Patterson was born on December 17, 1876, in Stoddard, Wisconsin, a small community in the southwestern part of the state. His parents were William and Alice (Outcalt) Patterson. He had an older brother, George, a younger brother, Clay, and a younger sister. Esther. A half-sister, Edna Outcalt, completed the Patterson family. When Roy was about 5 years old, the Pattersons moved to St. Croix Falls, in northwestern Wisconsin, where he lived the rest of his life. In the early 1890s he pitched and was an outfielder for the Millers, a team in nearby New Richmond, and other local teams.

In 1898 Patterson played for the Duluth (Minnesota) Dukes of the then amateur Northern League. He caught the attention of Charles Comiskey, owner and manager of the St. Paul Saints of the Western League. The Saints came to Duluth for two exhibition games in May 1898, but Patterson did not play for Duluth in either game. Years later Patterson recalled, “Well, I got out there and watched the game from a bleacher seat, and after looking at those fellows play; I got scared and went home. Gee, what fine players they were.”ii

But Comiskey continued his pursuit of Patterson and brought him to St. Paul for a trial in September. He didn’t stick and returned to Duluth a couple of weeks later. He started the 1899 season with Duluth again and was back in St. Paul in August, this time to stay. He had a 2-3 won-lost record for the Saints in his first season in Organized Baseball.

In 1900 Ban Johnson, president of the Western League, along with team owners like Comiskey began pushing to start a new major league. They formed the American League and Comiskey moved the Saints to Chicago, taking Patterson with him. After a slow start with the White Stockings, Patterson won 15 of his last 17 decisions, to finish 20-15. His only setbacks in that stretch were to Milwaukee’s Rube Waddell, a 12-inning 3-2 loss on August 16 and a 2-1 loss in 17 innings three days later.

Patterson found himself caught up in the middle of the bidding war between the established National League and the upstart American League. As early as August 1900, he was approached by agents from the Pittsburgh National League club and offered $3,500 to jump to the Pirates. Patterson always felt loyalty toward Comiskey because of the way Comiskey had helped him early in his career. After hearing the Pittsburgh offer, Patterson was said to be “much perplexed between cash and friendship,”iii but he turned it down and finished the season with the White Sox.

Comiskey obviously didn’t feel the same loyalty toward Patterson; immediately after the season he tried to sell his star pitcher to the crosstown Chicago Orphans. (Two years later they became the Cubs.) “Charlie has his eyes on young material, which, he says, will fill the gap which Patterson leaves,” a sportswriter commented.iv Orphans’ president James Hart even announced that he had purchased the release of Patterson from the White Sox. The Boston, Philadelphia, and Cincinnati National League clubs also put in claims for Patterson. But Ban Johnson, because of his cozy relationship with Comiskey, assured the White Sox owner that his star pitcher would be back in Chicago the next season, and he was. A short time later, Patterson signed a new contract with the White Sox for the 1901 season. In the middle of all this wheeling and dealing, Roy married Mabel G. Anderson on October 3, 1900, in Polk County, Wisconsin. The couple adopted a son, Norman, in 1903 and later had a daughter, Marion Grace, born in 1910.

In 1901 Patterson won 20 games (against 15 losses), his only 20-win season in his seven-year major-league career, leading the White Stockings to the first pennant in the American League as a major league. (No World Series was played until 1903.) He led the Chicago pitching staff in starts, complete games, strikeouts, and innings pitched, and was second to Clark Griffith (who won 24) in wins. Patterson’s 127 strikeouts were second in the American League only to Boston’s Cy Young. After a slow start in 1902 (a 2-5 record on June 7), Patterson had another fine season in 1902, winning a team-leading 19 games against 14 losses.

In 1903 Nixey Callahan became manager after Griffith moved to the helm of the New York Highlanders, and the White Sox fell to seventh place with a record of 60-77, Despite his 15-15 won-loss record, Patterson remained an effective pitcher. Now an established major-league pitcher, Patterson relied on a “puzzling variety of curves,” an “in shoot,” and a deceptive “drop” in his repertoire of pitches. He was never an overpowering pitcher, but was often described by sportswriters as “clever.”v

For the three seasons 1901-1903, Patterson was among the best pitchers in baseball. A rival manager said of him, “He is a fine looking chap, and has an easy, graceful delivery, with excellent command, good curves, and adequate speed.”vi But over those three seasons Patterson logged 873 innings and completed 82 of 95 starts. He developed a sore elbow and never returned to top form the rest of his major-league career. Despite Patterson’s fine season in 1903, Chicago owner Comiskey, fearing his usefulness was over, tried to cut his pay the next season. Patterson responded by holding out most of spring training, saying he “will not join the White Stockings under a reduced salary.”vii He eventually signed and joined the club in May.

In 1904 Patterson pitched in just 22 games and had a 9-9 record despite an excellent ERA of 2.29. Although still bothered by a sore elbow, he could still pitch effectively on occasion. In his last start of the season, on September 24, he shut out Philadelphia and Eddie Plank 3-0, holding the Athletics to three hits. In 1905 Patterson was limited to just 13 games, but had a 1.83 ERA.

Patterson regained some of his old form in 1906, going 10-7 with a 2.09 ERA in 142 innings. At the beginning of June, the White Sox were five games below .500, but in early August they were in fourth place. On August 8 the White Sox, behind Patterson, edged Plank and the Philadelphia A’s 1-0 in ten innings. Two weeks later Patterson beat Washington 4-1‚ giving Chicago its 19th straight win‚ an American League record that was tied by the 1947 Yankees. Chicago now led by 5½ games, but throughout September the lead went back and forth between the White Sox and the New York Highlanders, with the White Sox eventually winning the pennant by three games.

The 1906 team earned the nickname Hitless Wonders because its batting average was only .230. The White Sox made up for their lack of hitting with speed, defense, and outstanding pitching. Patterson was a part of a pitching staff that included Nick Altrock, Frank Owen, Ed Walsh, and Doc White. The White Sox advanced to the World Series against the highly favored Cubs, winners of 116 games in the National League. The Hitless Wonders batted just .198 as a team in the Series but upset the favored Cubs in six games. Because of overwork down the stretch, Patterson’s elbow problems resurfaced, and he did not pitch in the World Series.

Late in 1906 it was suggested that Patterson was being “carried” by Comiskey for sentimental reasons.viii Early in 1907 he experimented with a spitball in an attempt to prolong his career. An optimistic report In May said Patterson had “come back to life this season and will be pitched regularly by Chicago now that his arm is in condition,” adding, “The Boy Wonder is working to get control and he believes he will be able to master [the spitball] well enough to use it in some of his games before long. Patterson is in his best form right now.”ix However, Patterson went just 4-6 in 19 games and at the end of the season he was released by Comiskey. The next season he began a minor-league career that lasted for 14 seasons.

After being released, Patterson considered an offer to manage the Superior (Wisconsin) Northern League club, near his home, and pitch when he was able. He signed instead with the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association for 1908. Patterson had something of a rebirth in Minneapolis, winning 21 games for the Millers that season. He won 20 or more games again in 1910, 1911, and 1912, and was a key member of the Millers’ American Association pennant-winning teams those three years.

Patterson had two more successful seasons in Minneapolis, 1913 and 1914, although his 1913 season was interrupted when he was called home to St. Croix in July after his father died. Patterson signed on as player-manager of the Northern League’s Winnipeg Maroons in 1915. However, he clashed with team owner John Burmeister and was fired on July 8. He was quickly signed by the league’s Fargo Graingrowers, who were in second place, 12 games out, at the time. Patterson’s managing and pitching led the Fargo club to a 42-25 record the rest of the way, enough to win the league championship. For the season, his pitching record was 21-5.

In 1916 Patterson returned to the Western League with St. Joseph, Missouri, and compiled a 12-11 record before leaving the team in August. Before the 1917 season, he weighed an offer to purchase the Duluth Northern League team, where he would pitch and manage. Instead the 40-year-old Patterson decided to return to the Minneapolis Millers, who, like most of minor-league teams, faced a severe player shortage because of the World War. He joined Minneapolis in June, and his first start, on the 29th, was proclaimed Roy Patterson Day at Nicollet Park, the Millers’ home field. Patterson pitched just eight games for the Millers, but still had something left as he posted a 5-3 won-loss record and the lowest ERA (1.50) in the American Association.

Patterson posted another 5-3 record in limited action for Minneapolis in 1918. The next year Minneapolis manager Joe Cantillon wanted to use Patterson as a coach, but Patterson insisted that he was as “good as ever,” and he defeated Milwaukee in a complete game in his first start. But Patterson pitched in just three more games for the Millers before leaving the team for his farm in Wisconsin. He spent the rest of 1919 and the summer of 1920 pitching for independent teams in northern Minnesota.

In 1921 Minneapolis brought Patterson back again, this time exclusively as a pitching coach. But while the club was in spring training in Oklahoma City, Patterson was offered the manager’s job with the Breckenridge-Wahpeton Twins in the Dakota League. Bolstered by some of the Minneapolis castoffs, Patterson led the Twins to a winning record while winning eight games against five losses on the mound himself. The next season, the Twins were raided by new league entry Fargo, and had a losing record. Patterson had a 3-6 pitching record in his last season of professional baseball.

An incident in 1921 provided some insight into Patterson’s makeup and the kind of respect he commanded on the diamond. His Twins were playing the Huron club at home on July 12. The Twins were losing 3-2 in the ninth and had a runner on third, The Huron shortstop fielded a grounder and threw to the plate, where the runner was called out. Twins fans went wild and began hurling bottles and cushions at the umpire. Patterson, who had a good view of the play from behind the plate, rushed to the front of the stands and held up his hands to quiet the crowd. “I saw the play myself,” he said. “Our man was out. The umpire was correct. If you have any fight, take it out on our baserunner.” The fans quieted down immediately. “Never saw anything like that before in baseball,” said Mike Cantillon, president of the Dakota League. “It shows you what sort of fellow Patterson is.”x

In 1923 Patterson was named to the umpiring staff in the Western League, but after just one season he returned to Wisconsin. That fall he took over his father’s business hauling freight from the train depot to local businesses, first with horses and then by truck. In the early 1940s, he sold the business and moved into semiretirement, but then purchased the contract to carry packages and freight in St. Croix Falls and mail between his hometown and Dresser, Wisconsin.

In 1927 several newspapers reported that Patterson – “the former White Sox hurler” – had died destitute in an almshouse in Norristown, Pennsylvania, but it turned out that he had been confused with another Roy Patterson. Roy joked that he appreciated the outpouring of condolences for his wife, but that she was not a widow yet.xi

After returning to St. Croix Falls, Patterson continued to be an avid baseball fan, listening to radio play-by-plays the rest of his life and following the local teams. In the 1930s Patterson umpired local baseball tournaments and he remained in good physical condition by playing tennis and swimming in the summer and skating and playing hockey in the winter. He was designated the King of St. Croix Falls for the city’s centennial celebration in 1938.xii

In April 1949 the Minneapolis Millers brought Patterson back to help celebrate their 50th anniversary, having him throw out the ceremonial first pitch of the season. In May 1951 he went to Boston to participate in a 50th anniversary reunion of the first American League game in that city. Two years later, on April 14, 1953, he died at the age of 76 from a heart attack while driving in St. Croix Falls. He had managed to pull his car off to the side of the highway and was found with his hand still on the wheel of the automobile. Patterson was survived by his wife, daughter, and a grandson. He was buried at the St. Croix Falls Cemetery.

Mabel Patterson continued to live in St. Croix Falls, where she taught music and worked as a reporter for the local paper, the St. Croix Standard-Press. On April 16, 1965, the White Sox honored Patterson and Mabel threw out the first pitch in a game at Comiskey Park. Mabel died in 1970 at the age of 88 and is buried next to Roy in the St. Croix Falls Cemetery.

Sources

Braatz, Rosemarie Vezina, St. Croix Tales and Trails (Self-published, 2005.)

Eriksmoen, Curt, “Pitcher Roy Patterson Played in North Dakota,” Bismarck (North Dakota) Tribune, February 10, 2013.

http://www.ancestry.com

http://www.Baseball-Reference.com

http://www.usfamily.net/web/trombleyd/DakotaNotables.htm#Roy%20Patterson

Notes

i Sporting Life, September 22, 1900.

ii Denver Post, January 24, 1918.

iii Washington Evening Star, October 19, 1901.

iv St. Paul Daily Globe, October 4, 1901.

v Kansas City Star, august 26, 1900.

vi Boston Herald, February 1, 1903.

vii Chicago Tribune, March 21, 1904.

viii Sporting Life, August 25, 1906.

ix Pittsburgh Press, July 15, 1907.

x Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, July 13, 1921.

xi Cleveland Plain Dealer, November 4, 1927.

xii Rosemarie Vezina Braatz, St. Croix Tales and Trails (Self-published, 2005).

Full Name

Roy Lewis Patterson

Born

December 17, 1876 at Stoddard, WI (USA)

Died

April 14, 1953 at St. Croix Falls, WI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.