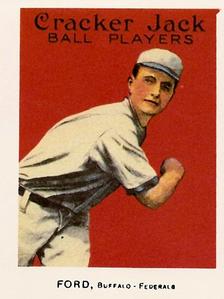

Russ Ford

The first player born in the western Canadian province of Manitoba to reach the major leagues, Russ Ford burst into the spotlight in 1910, winning 26 games for the New York Highlanders with a baffling new pitch never before seen in professional baseball. Using a piece of emery board hidden in his glove, Ford roughed up one side of the ball, causing it to break at odd angles depending on how he threw it. For two seasons, Ford used the emery ball to dominate the American League, all the while hiding the origin of his new discovery. “He kept his secret a long time by pretending he was pitching a spitter,” Ty Cobb later recalled. “He would deliberately show his finger to the batter and then wet it with saliva.” Though Ford’s signature pitch was banned by 1915, his invention set the precedent for a long line of scuff ball artists, including contemporaries Cy Falkenberg and Eddie Cicotte and Hall of Famers Whitey Ford and Don Sutton.

The first player born in the western Canadian province of Manitoba to reach the major leagues, Russ Ford burst into the spotlight in 1910, winning 26 games for the New York Highlanders with a baffling new pitch never before seen in professional baseball. Using a piece of emery board hidden in his glove, Ford roughed up one side of the ball, causing it to break at odd angles depending on how he threw it. For two seasons, Ford used the emery ball to dominate the American League, all the while hiding the origin of his new discovery. “He kept his secret a long time by pretending he was pitching a spitter,” Ty Cobb later recalled. “He would deliberately show his finger to the batter and then wet it with saliva.” Though Ford’s signature pitch was banned by 1915, his invention set the precedent for a long line of scuff ball artists, including contemporaries Cy Falkenberg and Eddie Cicotte and Hall of Famers Whitey Ford and Don Sutton.

Russell William Ford was born in Brandon, Manitoba on April 25, 1883, the third of five children of Walter and Ida Ford, a second cousin of future U.S. President Grover Cleveland. When Russell was three years old, his family immigrated to the United States, eventually settling in Minneapolis, where Walter worked as a clerk. Following high school, Russ spent several years pitching in the minor leagues. In 1905 the 5’11”, 175-pound right-hander debuted with the Cedar Rapids Rabbits of the Three-I League. That same year, Ford’s older brother Gene, who had been born in Nova Scotia, briefly appeared in the major leagues as a pitcher for the Detroit Tigers. After winning 22 games for Cedar Rapids in 1906, Russ moved up the professional ladder to the Atlanta Crackers of the Class A Southern Association, where he won a total of 31 games in 1907 and 1908. His success in Atlanta led the New York Highlanders to draft him prior to the 1909 season. Primarily a spitball pitcher, Ford made his major league debut against the Boston Red Sox on April 28, 1909, pitching three innings in relief, surrendering four runs, three of them earned, on four hits, four walks, and three hit batsmen. The New York Times noted that “the cold weather seemed to affect” Ford, but the Highlanders, unimpressed, farmed the 26-year-old out to the Jersey City Skeeters of the Eastern League.

In a 1935 interview with The Sporting News, Ford explained that he first discovered the secret behind the emery pitch in 1908, when he was still with Atlanta. On a rainy spring morning Ford was warming up under the stands with catcher Ed Sweeney when he became wild. One pitch struck a wooden upright; another sailed sideways about five feet. When Sweeney returned the ball, Ford examined it and saw that it was rough where it had hit the upright. He wondered if the roughened surface was responsible for the ball’s odd movement, so he gripped the sphere on the side opposite its roughened surface and when he pitched it, the ball shot through the air with a sailing dip. “It never occurred to me that I had uncovered what was to become one of the most baffling pitches that a Cobb, Lajoie, Speaker or Delahanty [sic] would be called upon to bat against in the big leagues,” Ford told The Sporting News.

After being demoted to Jersey City in 1909, Ford returned to his discovery and conducted additional experiments during batting practice. At first he used a broken pop bottle to scuff the ball deliberately. After his teammates missed hitting the ball by as much as 12 to 18 inches in practice, Ford began employing the scuff ball during games, using a small piece of emery he carried in his glove. Throughout the season, Ford worked on various ways of concealing the pitch, which helped him strike out 189 Eastern League batters.

Ford’s solid performance in Jersey City earned him another shot with the Highlanders at the start of the 1910 season. Now armed with the emery pitch–which he continued to disguise as a special kind of spitball called the “slide ball”–Ford authored one of the finest rookie pitching seasons in baseball history. In his first major league start, Ford struck out nine batters, walked none, and shut out the Philadelphia Athletics, 1-0. By the end of the season, Ford ranked second in the league in wins (26) and tied for second in shutouts (8), while posting a brilliant 1.65 ERA, seventh best in the league. With 209 strikeouts and 70 walks, he also boasted the fourth best strikeout-to-walk ratio in the league. Ford’s 26 victories also established the American League rookie record, which still stands. Thanks in large part to Ford’s dominating performance, the Highlanders finished in second place with an 88-63 record, their best showing in four years.

Ford continued to guard the secret of his new pitch, boasting to the press that he had 14 different versions of his “spitball.” “Ford worked cleverly,” umpire Billy Evans recalled. “He had the emery paper attached to a piece of string, which was fastened to the inside of his undershirt. He had a hole in the center of his glove. At the end of each inning he would slip the emery paper under the tight-fitting undershirt, while at the start of each inning he would allow it to drop into the palm of his glove.”

In 1911 the Highlanders slumped to sixth place, but Ford continued to rank among the best pitchers in the league, posting a 22-11 mark with a 2.27 ERA. On July 24 Ford also pitched for the all-star team that played a benefit game against the Cleveland Naps in the wake of pitcher Addie Joss‘s death, hurling four innings in relief of Joe Wood and Walter Johnson. Another measure of respect came the following spring, when Ty Cobb spoke to a Baseball Magazine reporter about his participation in a vaudeville tour through the South. A month of one-night stands was worse than facing Walter Johnson or Russ Ford 154 games in the season, Cobb said.

But opposing batters had a much easier time handling Ford’s deliveries in 1912, as the pitcher lost a league-high 21 games, though his 3.55 ERA was still slightly better than the league average. By the following year, the secret behind the emery pitch had also made its way around the league, and the delivery was picked up by Cleveland right-hander Cy Falkenberg, who used it to win 23 games in 1913. That year, Ford battled through a fatigued right arm to post a 12-18 record with a solid but unspectacular 2.66 ERA. In a sign of his reduced strength, Ford struck out just 72 batters in 237 innings, a distant cry from the dominance he displayed as a rookie three years earlier

When New York offered him a cut in pay in 1914, Ford moved to the new Federal League, where he went 21-6 and posted a 1.82 ERA (second best in the league) with Buffalo. Ford’s .778 winning percentage led the league, as did his 3:1 strikeout to walk ratio and his six saves. It proved to be the last great season of his career, however, as the emery ball, already illegal in the American League, was banned by FL President James Gilmore in 1915. Deprived of his signature pitch and again nursing a sore arm, Ford struggled to a 5-9 record for Buffalo before the club released him on August 28, ending his major league career.

Following his release from the Federal League, Ford pitched two more seasons in the minors with Denver of the Western League and Toledo of the American Association. After his baseball career ended, Ford lived with his wife, Mary Hunter Bethell, whom he had married in 1912. The couple had two daughters, Mary and Jean. Ford worked in Newark, New York City and in Rockingham, North Carolina, near his wife’s hometown. He died of a heart attack in Rockingham on January 24, 1960, at age 76. His cremated remains were buried in Rockingham’s Leak Cemetery. In 1989, Ford was inducted into the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame; his 2.59 career ERA remains the best of any Canadian-born pitcher.

Note

This biography originally appeared in David Jones, ed., Deadball Stars of the American League (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, Inc., 2006).

Sources

Jim Shearon. Canadian Baseball Legends. Malin Head Press, 1994.

William Humber. Diamonds of the North. Oxford University Press, 1995.

Paul Dickson. The Dickson Baseball Dictionary. Facts on File, 1989.

Rick Brownlee. Manitoba Sports Hall of Fame. 2002.

Jim Charlton. Road Trips. SABR, 2004.

Lyle Spatz. SABR’s Baseball Records Committee. 2000.

John Thorn and Pete Palmer. Total Baseball 1989.

Baseball Magazine. 1912, 1913, 1915.

Full Name

Russell William Ford

Born

April 25, 1883 at Brandon, MB (CAN)

Died

January 24, 1960 at Rockingham, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.