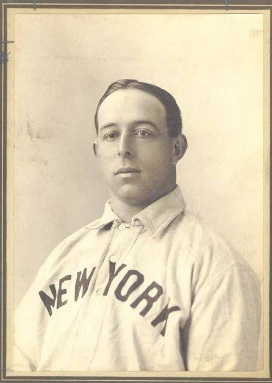

Sam Mertes

Sam Mertes possessed a rare combination of speed and power. From 1899 to 1905, he was routinely among the league leaders in stolen bases, triples, and home runs. He was an outstanding defensive outfielder. Gritty and energetic, Mertes harassed opponents and umpires in his foghorn voice. He had the physique of a heavyweight boxer and was nicknamed “Sandow” after a famous strongman of his era. “I doubt if there has been a man on the New York team who could hit the ball further than Mertes,” said New York Giants manager John McGraw in 1909.1

Sam Mertes possessed a rare combination of speed and power. From 1899 to 1905, he was routinely among the league leaders in stolen bases, triples, and home runs. He was an outstanding defensive outfielder. Gritty and energetic, Mertes harassed opponents and umpires in his foghorn voice. He had the physique of a heavyweight boxer and was nicknamed “Sandow” after a famous strongman of his era. “I doubt if there has been a man on the New York team who could hit the ball further than Mertes,” said New York Giants manager John McGraw in 1909.1

Samuel Blair Mertes (pronounced MUR-teez) was born on August 6, 1872, in San Francisco. His parents were Peter Mertes, of German descent, and Mary A. McCloy, of Scottish descent. Peter was a seaman, laborer, and newspaper carrier;2 he died when Sam was 5 years old.3 Box scores in San Francisco newspapers show that “Mertes” (Sam and his brothers) played on local teams from 1890 to 1893. Sam was 5-feet-10 and weighed 185 pounds. He was a right-handed batter and thrower.

In 1894 Sam played for Lincoln (Nebraska), Jacksonville (Illinois), and Quincy (Illinois) in the Class A Western Association.4 He is “one of the hardest hitters and fastest baserunners” in the league, reported Sporting Life, and he “covers a great deal of ground in the outfield and is an accurate long-distance thrower.”5 In the offseason he married Mary E. McGlynn, a San Franciscan of Irish descent.

In 1895 Mertes batted .345 in 85 games for Quincy and led the league with 13 home runs.6 By mid-July he had stolen 50 bases.7 In the fall he played for Los Angeles in the California League, where he was noticed by Charlie Comiskey, owner and manager of the St. Paul (Minnesota) team in the Class A Western League. Comiskey signed him to a contract for the 1896 season and said, “That man Mertes is a wonder. Wait till you see him.”8 Mertes fulfilled Comiskey’s expectations, batting .354 in 49 games for St. Paul,9 and was considered the star outfielder in the league.10 The Cincinnati Enquirer described him:

“Although of heavy build, he is as quick as a flash on his feet. … He is a natural hitter, and his great strength enables him to rap out drives that the infielders are glad to shirk. On the base lines he keeps the best of the catchers guessing, rarely having to slide to complete a steal. It is believed that fast company will have no terror for him, for if he has any trait in prominence, it is self-confidence.”11

The Indianapolis News thought Mertes was too confident: While he “is a clever young player, prosperity has spoiled him and he is swelled on himself.”12

In June Comiskey traded Mertes to the Philadelphia Phillies of the National League. He arrived in Brooklyn for his major-league debut on June 30 with no uniform, so he borrowed one from a Brooklyn player. He was inserted into the Phillies’ starting lineup as the leadoff hitter and center fielder. The Phillies lost the game 5-4, but Mertes “created a good impression.”13 He walked in the first inning and scored a run, and in the third inning, he lined a single past the head of pitcher Dan Daub for his first major-league hit. The next day Mertes “distinguished himself by making some marvelous catches” in the Phillies’ 5-2 victory over Brooklyn.14

Mertes was the fastest man on the Phillies.15 He had no trouble stealing bases on major-league catchers, and he shined in center field. On July 15 he reached into the bleachers to steal a home run from Chicago’s Bill Everitt.16 Mertes made seven catches on July 23, including one in which he “had a long run in, stooped for the ball, caught it and rolled over, but hung on to the ball throughout his somersault and came up smiling.”17 Chicago’s Cap Anson called him “the freshest thing that ever happened.”18

Although Mertes turned heads with his baserunning and fielding, he struggled at the plate against major-league pitching. Sportswriter Joe Corbett said Mertes must “learn to meet the ball for a base hit instead of endeavoring to knock the cover off” by swinging with all his might.19 The Phillies sent him to the Class A Atlantic League in late August to work on his hitting while playing for the Wilmington (Delaware) Peaches and the Philadelphia Athletics. On the Athletics, he developed a reputation as a “kicker,” a player who habitually complained about umpires’ calls and was frequently ejected.20 He later explained his purpose:

“We were scheduled for a lot of doubleheaders. … I had a bad leg but was forced into two games every day. This was my plan to escape playing: I would take umbrage at some fancied bad decision on balls and strikes, or some other play, and would run up and roar like a wild man at the umpire. … This of course would make him sore and he would order me out of the game. … The custom became so popular that some days it was almost impossible to get enough players to finish out the game.”21

Mertes returned to the Phillies in mid-September. In 37 games for the Phillies in 1896, he batted .238 and stole 19 bases. He played for the “San Franciscos” in the fall California League, and in February 1897 the Phillies sold his contract to the Columbus (Ohio) Senators of the Western League.22 He would have to work his way back to the National League.

In 1897 Mertes hit .337 in 134 games for Columbus, scored 155 runs, and led the league with 97 stolen bases. He slid with spikes flying, which earned him the nickname “Mertes the Spiker.”23 According to Sporting Life, Mertes was considered the dirtiest player in the league.24 In an August game at St. Paul: “Mertes attacked [Jack] Glasscock, apparently without cause. A few light blows were exchanged, but no blood was spilled,” and Mertes was ejected from the game.25 Nonetheless, St. Paul manager Comiskey considered Mertes to be the best player in the league.26

After playing 18 games for Columbus in 1898, Mertes returned to the National League in mid-May as a member of the Chicago Orphans (the predecessor of the Chicago Cubs). On May 27 he doubled with the bases loaded and drove in three runs in an 8-2 victory over his old team, the Phillies.27 On June 29, with two men on base, he hit his first major-league home run, off Jouett Meekin in a 12-4 defeat of the Giants.28 On the Fourth of July against Cy Young and the Cleveland Spiders, Mertes scored the tying run in the eighth inning by stealing home (his third steal of the game) and then singled in the winning run in the ninth inning with his fourth hit of the game.29 Mertes was “the find of the year,” inspirational to his teammates, and the “best all-around player” on the team, playing second base, shortstop, and all three outfield positions.30

Where rowdies cross paths, trouble can ensue. Boston first baseman Fred Tenney was an expert at “jostling, blocking, and throwing baserunners.”31 In a game on August 16, Mertes ran down the first-base line, and as he reached the bag, he was thrown 15 feet by Tenney’s hip-check. Mertes vowed revenge and got it two days later when he ran to first base and spiked Tenney’s leg. Sporting Life decried the “dirty playing.”32 In a game at Philadelphia on September 16, Mertes argued a close play at home plate and was ejected from the game. When he refused to leave the field, the umpire declared the game forfeited to the Phillies.33 Mertes’ senseless “kicking” cost the Orphans the game. He batted .297 in 83 games for Chicago in 1898, and in the fall, he played in California for Stockton and Watsonville.

On July 13, 1899, Mertes hit a single, double, and triple in Chicago’s 9-4 victory over Boston; he stole home off pitcher Ted Lewis and made a “sensational one-hand catch” in deep center field.34 On August 9 in Washington, he made two spectacular catches in right field and had three hits, including a triple off the scoreboard.35 On August 20 against Cleveland, he stepped to the plate in the bottom of the ninth inning with the bases loaded and Chicago trailing 7-5. He delivered a walk-off triple to win the game and then doffed his cap to the cheering fans.36 Eight days later in Chicago, Mertes caught a line drive in deep left field and pegged a “perfect throw” to first base to complete a double play; it was “one of the most marvelous feats seen here this season.”37

Mertes demonstrated his home-run power late in the season. On September 19 he homered to deep left field in Chicago’s 4-2 defeat of Brooklyn.38 In the first game of a doubleheader on September 24, he amazed spectators by blasting two home runs over the center-field fence in Cincinnati; on average, only five balls were hit over that fence each season.39 One of Mertes’ blasts did some real damage:

“Just back of the [Cincinnati] park is a saloon, the occupants of which always thought themselves protected, but the awakening was dear. … [Mertes’ home run] tore up a mechanical advertising apparatus costing over $50, and still unimpeded, smashed through a plate-glass window, struck the center of a table, breaking up a pinochle game, and then bounded over the bar into the cut-glass ware on the shelves. When the wreckage had been cleared up, a bill was presented to the baseball management for $64 [in] damages. The ball now hangs in that saloon as a trophy.”40

Mertes wrapped up the year with two homers in a doubleheader on October 8, the second one off Louisville rookie Rube Waddell.41 For the season, Mertes batted .298 in 117 games and ranked in the top eight in the league in stolen bases (45), triples (16), home runs (9), and slugging percentage (.467). In the offseason he worked as a carpenter in San Francisco.42

In 1900 Mertes batted .295 for the Orphans and stole 38 bases. He played in 127 games, including 33 games at first base, filling in for the injured John Ganzel. Mertes’ hitting at Boston on June 8 and 9 was exceptional, with three home runs and two doubles in two games. He led off the game on June 8 by sending the first pitch from Bill Dinneen over the left-field fence and “into the cab of a passing [train] engine.”43 He hit a second homer off Dinneen in the seventh inning with two men on base. The next day Mertes led off the game with an opposite-field home run off Ted Lewis.44

In 1901 Mertes jumped to Comiskey’s Chicago White Sox in the newly formed American League, and on April 24 he played in the league’s first game and scored two runs in Chicago’s 8-2 victory over Cleveland.45 On May 23 he hit a three-run homer off Philadelphia rookie Eddie Plank. Mertes batted .277 and drove in 98 runs in 137 games, and helped the White Sox win the AL pennant. His 46 stolen bases ranked second in the league. He played second base throughout the season and recorded the second highest fielding percentage among AL second basemen. There was some controversy during the season: In Washington on August 19, Mertes “made an attack” on umpire John Haskell which required police intervention,46 and in Boston on September 24, he was ejected in the first inning when he told umpire Tommy Connolly to “umpire right.”47

Mertes returned to the outfield and repeatedly came through with clutch hitting during the 1902 season. His 10th-inning three-run homer off Dinneen gave Chicago a 4-3 victory over Boston on May 22.48 In the second game of the July 4 doubleheader against Cleveland, the White Sox trailed 2-1 in the bottom of the ninth inning when Mertes came to bat with two on and two out; he stroked a triple to right-center field to drive in the tying and winning runs.49 A week later, he knocked in the winning run in the bottom of the ninth inning in a 2-1 victory over St. Louis.50 From left field, Mertes threw out runners at the plate on August 4 and August 9,51 and his daring catch of a foul fly on September 11 “carried him headlong into the bleacher fence.”52 He finished the season with a .282 average in 129 games. He was second in the league with 46 stolen bases, and he led the league with 26 outfield assists.

Mertes returned to the National League in 1903 by signing a contract with the New York Giants at “a great increase in salary.”53 In his first season playing for manager John McGraw, Mertes was a sensation. Sporting Life reported in May: “Sandow Mertes has strengthened the Giants immensely in batting and baserunning, and no player who ever wore a New York uniform was ever more popular. His long hits have been a feature in nearly every game.”54 At the end of May, Mertes was tied for the league lead with a .382 batting average.55 He finished the season at .280 in 138 games for the second-place Giants. He stole 45 bases, scored 100 runs, and led the league with 104 runs batted in. His 53 extra-base hits were second in the league behind Honus Wagner’s 54. Mertes played left field, the notoriously difficult “sun field” at New York’s Polo Grounds, yet, remarkably, he led NL outfielders with a .973 fielding percentage. His 24 outfield assists were second in the league. He was a “five-tool” player who excelled at hitting for average and power; fielding and throwing; and running the bases.

The 1904 Giants won 18 games in a row from June 16 to July 4, and went on to win the NL pennant. Mertes went 4-for-4 with a home run and four RBIs in a 5-2 defeat of Cincinnati on July 15.56 In the second game of the September 5 doubleheader in New York, Mertes knocked in the winning run in the bottom of the ninth inning against Boston. Excited fans rushed onto the field; McGraw was trampled by the mob and required a trip to the hospital.57 On October 3 Mertes’ eighth-inning double drove in two runs to give the Giants a 2-1 lead over St. Louis, as Christy Mathewson won his 33rd game of the year.58 The next day Mertes hit for the cycle and scored all three runs in New York’s 7-3 loss to the Cardinals.59 He finished the season with a .276 average in 148 games and was tied for second in the league in both RBIs (78) and stolen bases (47). There was no World Series, though; Giants owner John T. Brush refused to play the AL champion Boston Americans.60 McGraw praised Mertes for going “through two seasons at the Polo Grounds playing left field in that terrible sun” while making so few mistakes. Mertes called McGraw “the best manager on earth.”61

Mertes arrived at spring training in 1905 with his bulldog, Happy. The likable canine quickly became the team mascot and was popular with Giants fans.62 Happy scampered around Mertes during fielding practice at the Polo Grounds and “would get the ball between his jaws and tear playfully around” the field with it.63

On May 17, 1905, Mertes’ three-run homer off Carl Lundgren provided the margin of victory over Chicago.64 Mertes knocked in the go-ahead run on July 20 in a 2-1 triumph over St. Louis, and the next day he hit a grand slam off the Cardinals’ Jack Taylor.65 On July 30 at Cincinnati, the Giants were leading 2-1 when Mertes snuffed out a Reds rally:

“With [Admiral] Schlei on second, [Bob] Ewing on first and one gone in the fifth, [Miller] Huggins raised a short fly to left. Mertes was playing in close for the left-handed hitter, and the ball was knocked directly into his hands, a slow, loop fly. As it was a certain out, Schlei and Ewing hugged their bases, which gave Sandow a chance to turn a clever trick. Just as the ball got to him he lowered his hands and took it after it had struck the ground. That, of course, forced Schlei and Ewing [to run], but neither of them was sure that Sandow had not caught the ball on the fly. Their uncertainty made the play easy for Mertes, who threw to Billy Dahlen at second base. Dahlen had only to touch Schlei and then step on the bag, forcing Ewing, to complete the double [play], which retired the side.”66

The Giants traveled to Chicago for a four-game series, August 7-10, and arrived in time to attend the Boston-Chicago game on August 6. Umpire Jim Johnstone, who was injured by a foul tip the day before, was unable to work the game. Mertes volunteered to fill in as the umpire, and according to the Chicago Daily Tribune, he did “one of the best jobs of umpiring that has been seen in Chicago this season.”67 His teammates, though, enjoyed razzing him on every close call.68

The Giants needed one more win to clinch the NL pennant when they played the first game of a doubleheader at Cincinnati on October 1. The score was tied 4-4 after nine innings. The Giants went ahead 5-4 on Mertes’ 10th-inning triple, which Reds center fielder Cy Seymour lost in the sun.69 Giants center fielder Mike Donlin was also struggling with the sun, so McGraw moved Donlin to left field and Mertes to center field for the bottom of the 10th. With two outs and a man on second base, the Reds’ Harry Steinfeldt “hit the ball [with] an awful crack and it went toward center like a bullet.”70 McGraw described Mertes’ extraordinary play:

“Starting with the crack of the bat, he looked squarely into the sun and ran with the ball. It seemed certain that it would go over his head. By a sprint, though, he got back and with a jump speared the ball with his bare hand, crashing into the fence as he fell. But he had saved the game and won the pennant.”71

The Scranton Truth reported the reaction to his play:

“The throng of spectators were simply dumbfounded, and as Sam came in across the diamond, he was given the greatest ovation a ballplayer ever received. Five minutes after Mertes made the wonderful catch, [Giants] Secretary [Fred] Knowles secured the ball and now has it covered with gold leaf ready for an inscription. It will be kept in the headquarters in New York and will be prized as one of the club’s greatest trophies.”72

In 1923 McGraw said that Mertes’ catch was one of the two best catches he had ever seen.73 Mertes finished the 1905 season with a .279 average and 52 stolen bases in 150 games. He was second in the league with 108 runs batted in. The Giants finished nine games ahead of the second-place Pittsburgh Pirates, and this time the Giants were willing to play the AL champions in the World Series.

In Game One of the 1905 World Series against the Philadelphia Athletics, Mertes drove the ball into the crowd in center field in the fifth inning. Philadelphia center fielder Bris Lord made a fine leaping catch but dropped the ball when he collided with spectators.74 This hit knocked in the Giants’ second run in a 3-0 victory. In Game Two Mertes was held hitless and was struck out twice by Chief Bender, who delivered a 3-0 shutout. In Game Three Mertes singled and drove in a run in the Giants’ 9-0 rout.

Game Four was a pitching duel between Eddie Plank and Joe McGinnity. In the fourth inning Mertes reached first base on an error by shortstop Monte Cross and then advanced to second on a sacrifice. Billy Gilbert singled to short left field, and Mertes dashed home with the only run of the game. With the Giants protecting a 1-0 lead in the ninth inning, Danny Murphy drove the ball to deep left field; “Mertes, shading his eyes with his glove, ran back sideways and pulled down the ball an instant before he hit the fence.”75 In the Series finale, Mertes walked and scored the first run in the Giants’ 2-0 victory, as Mathewson outdueled Bender in New York. After the final out, the world champions ran to the clubhouse as jubilant fans rushed onto the field.

“A crowd of at least 5,000 got as near to the clubhouse as they could get and refused to budge. Finally, the members of the team were forced to come out on the veranda and bow their acknowledgements to the thunderous applause. Someone started a yell for souvenirs and Mertes started the game by throwing out his glove to the sea of upturned faces below. … Other players followed suit, and soon old balls, caps and various portions of uniforms came hurling through the air…”76

After the Series Mertes returned to San Francisco, where he looked after his newspaper route. He had “a contract to deliver newspapers to all the newsstands and subscribers in a section” of the city.77 He took time out to go rabbit hunting in Colorado with his former Chicago teammate, Bill Everitt, who was manager of the Denver Grizzlies of the Western League.78

On March 10, 1906, Mertes and his sidekick Happy arrived at Giants spring training in Memphis, Tennessee.79 The Giants opened the season at Philadelphia on April 12. The team was in Brooklyn when the news broke that San Francisco had been hit by a devastating earthquake on April 18. This, of course, was deeply concerning to Mertes, who waited anxiously for word from his family. His wife was pregnant with their first child and was probably in San Francisco at the time of the quake. He finally received a letter from his brother on April 29 indicating that some relatives “lost all of their property but [all] are well and glad to be alive.”80 Mertes’ house at 2526 McAllister81 was west of the fires that destroyed much of the city. A refugee camp was set up at Golden Gate Park near his house.82 Mertes continued on as the Giants left fielder, but the crisis in San Francisco weighed heavily upon him.

Through his first 40 games of the season, Mertes batted .263,83 but he hit only .183 over his next 29 games. He was stunned and greatly disappointed when McGraw traded him to the Cardinals on July 13. In Mertes’ final two games with the Giants, on July 11-12, he went 5-for-11 with a home run and a triple.84 At first he balked at reporting to the Cardinals, but he made his first appearance with the team on July 16 in a game against the Giants and “made a great catch of [Roger] Bresnahan’s foul to deep left.”85 Mertes was so discouraged by McGraw’s loss of confidence in him that he considered quitting the game.86 In 53 games for St. Louis, Mertes batted .246, but his heart was not in it. He returned to San Francisco, where his son, David Everitt Mertes, was born on October 15. In the offseason Sam worked in construction in the rebuilding city.

In March 1907 the Boston Doves of the National League acquired the rights to Mertes from the Cardinals; however, the Doves wanted to cut his salary from $4,000 to $2,400. Mertes filed a grievance with the National Commission, which ruled that either the Cardinals or the Doves must pay him $4,000 if he were to play for one of them in 1907.87 Both teams declined to pay that amount, and Mertes was declared a free agent. He signed with the Minneapolis Millers of the Class A American Association at reportedly “one of the largest salaries ever paid a player by a minor league club.”88 He batted .280 in 115 games for the Millers, but deserted the team in midseason for a month, purportedly to visit an ill relative on the West Coast.89 He was released by the team after the season.

Mertes signed with the Toronto Maple Leafs of the Class A Eastern League for the 1908 season, but after hitting .229 in 60 games, he was released, and he returned to San Francisco. His rapid fall from major-league stardom was surprising to observers,90 but his enthusiasm for the game had waned. He was now 36 years old and frustrated by his declining baseball skills. The game was no longer easy for him.

Frank Bowerman, who was Mertes’ teammate at New York, became the manager of the 1909 Boston Doves and offered Mertes a contract to join the team.91 Preferring to stay close to home, Mertes turned down the offer and instead joined the Stockton Millers of the California League. This was Mertes’ final season in professional baseball and it was an ugly one.

- On June 15 in Oakland, Mertes argued a called strike with umpire Pete Smith by stepping on Smith’s feet with his spikes. Smith responded with “a full right swing” to Mertes’ jaw and ordered him out of the game.92 Mertes waited outside the ballpark, and as Smith left the ballpark after the game, Mertes threatened to harm him if he returned to umpire another game.

- On June 27 in Santa Cruz, Mertes argued with the umpire and was ejected from the game, but refused to leave the field. He departed only after a policeman stepped in and beat him “into subjection” with a billy club.93

- On August 8 in Sacramento, Mertes fought with the umpire until both men’s faces were bloodied. Mertes “was taken to the county jail in an ambulance.”94

Many aging ballplayers retire from the game with dignity and class. Mertes was not one of them.

Mertes lived in San Francisco the rest of his life and was a carpenter, newspaper carrier, chauffeur, salesman, elevator operator, and real-estate broker.95 He died of a heart attack96 in Villa Grande, California, on March 11, 1945,97 at the age of 72.

From a vantage point atop Coogan’s Bluff in 1903, 14-year-old Harpo Marx had a good view of left fielder Mertes at the Polo Grounds and little else. In his memoirs, Marx paid tribute to his favorite ballplayer:

“Other kids collected pictures of Giants such as McGraw, McGinnity and Mathewson. Not me. I was forever faithful to Sam Mertes, undistinguished left fielder, the only New York Giant I ever saw play baseball. Eventually I came to forgive Sam for all the hours he stood around, waiting for the action to come his way. It must have been just as frustrating for him down on the field as it was for me up on the bluff. It was easy for pitchers or shortstops to look flashy. They took lots of chances. My heart was with the guy who was given the fewest chances to take, the guy whose hope and patience never dimmed. Sam Mertes, I salute you! In whatever Valhalla you’re playing now, I pray that only right-handed pull-hitters come to bat, and the ball comes sailing your way three times in every inning.”98

Notes

1 New York Evening Telegram, March 19, 1909.

2 San Francisco city directories, 1871-1877.

3 Daily Alta California, January 11, 1878.

4 Lincoln (Nebraska) Daily News, May 12 and 14, 1894; Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, July 11, 1894.

5 Sporting Life, November 3, 1894.

6 baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Western_Association.

7 Sporting Life, July 20, 1895.

8 Sporting Life, February 22, 1896.

9 St. Paul (Minnesota) Globe, July 12, 1896.

10 Sporting Life, June 27, 1896.

11 Cincinnati Enquirer, June 14, 1896.

12 Indianapolis News, June 25, 1896.

13 Philadelphia Times, July 1, 1896.

14 Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 2, 1896.

15 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 21, 1896.

16 Philadelphia Times, July 16, 1896.

17 Philadelphia Times, July 24, 1896.

18 Kansas City Star, July 30, 1896.

19 San Francisco Call, May 19, 1898.

20 Sporting Life, September 12, 1896.

21 Chicago Inter Ocean, March 25, 1900.

22 Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 19, 1897.

23 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 22, 1897.

24 Sporting Life, August 7, 1897.

25 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 18, 1897.

26 Chicago Daily Tribune, August 24, 1898.

27 Chicago Inter Ocean, May 28, 1898.

28 Chicago Daily Tribune, June 30, 1898.

29 San Francisco Call, July 5, 1898.

30 Louisville Courier-Journal, July 10, 1898; Sporting Life, July 16, 1898.

31 Cincinnati Enquirer, August 18, 1898.

32 Sporting Life, August 27, 1898.

33 San Francisco Call, September 17, 1898.

34 Chicago Inter Ocean, July 14, 1899.

35 Washington Morning Times and Chicago Daily Tribune, August 10, 1899.

36 Cleveland Plain Dealer, August 21, 1899.

37 San Francisco Call, August 29, 1899.

38 San Francisco Call and Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 20, 1899.

39 Chicago Inter Ocean, September 25, 1899.

40 Washington Post, October 21, 1906.

41 Chicago Daily Tribune, October 9, 1899.

42 San Francisco city directories, 1899, 1900.

43 Chicago Daily Tribune, June 9, 1900.

44 Chicago Daily Tribune, June 10, 1900.

45 Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 25, 1901.

46 Chicago Inter Ocean, August 20, 1901.

47 Boston Post, September 25, 1901.

48 Boston Post, May 23, 1902.

49 Chicago Inter Ocean, July 5, 1902.

50 Chicago Daily Tribune, July 12, 1902.

51 Chicago Inter Ocean, August 5, 1902; Washington Evening Star, August 11, 1902.

52 Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 12, 1902.

53 Scranton (Pennsylvania) Republican, September 6, 1902.

54 Sporting Life, May 16, 1903.

55 St. Louis Republic, May 31, 1903.

56 Scranton Republican, July 16, 1904.

57 New York Times, September 6, 1904.

58 Warren N. Wilbert, What Makes an Elite Pitcher? Young, Mathewson, Johnson, Alexander, Grove, Spahn, Seaver, Clemens, and Maddux (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003).

59 Sporting Life, October 15, 1904.

60 Sporting Life, October 8, 1904.

61 Sporting Life, November 5, 1904, and January 7, 1905.

62 Sporting Life, March 25 and April 29, 1905.

63 Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 21, 1930.

64 Scranton Republican, May 18, 1905.

65 Sporting Life, July 29, 1905; New York Tribune, July 22, 1905.

66 Cincinnati Enquirer, July 31, 1905.

67 Chicago Daily Tribune, August 7, 1905.

68 Sporting Life, August 19, 1905.

69 Scranton Republican, October 2, 1905.

70 Scranton Truth, October 5, 1905.

71 Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 9, 1923.

72 Scranton Truth, October 5, 1905.

73 Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 9, 1923.

74 Washington Times, October 10, 1905.

75 New York Tribune, October 14, 1905.

76 Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 15, 1905.

77 Sporting Life, November 4, 1905.

78 Sporting Life, November 25, 1905.

79 New York Times, March 11, 1906.

80 Scranton Truth, April 30, 1906; Sporting Life, May 5, 1906.

81 San Francisco city directories, 1905, 1908.

82 sfmuseum.org/hist2/ggpark4.html.

83 Sporting Life, June 9, 1906.

84 Sporting Life, July 21, 1906.

85 Sporting Life, July 28, 1906.

86 Anaconda (Montana) Standard, December 16, 1906.

87 Sporting Life, April 27, 1907.

88 Marion (Illinois) Daily Mirror, May 7, 1907.

89 Sporting Life, August 3, 1907.

90 Washington Post, May 12, 1908.

91 Sporting Life, May 1, 1909.

92 San Francisco Call, June 16, 1909.

93 Los Angeles Herald, June 28, 1909.

94 Los Angeles Herald, August 9, 1909.

95 San Francisco city directories and 1940 US Census.

96 The Sporting News, June 28, 1945.

97 California Death Index and funeral home records at ancestry.com.

98 Harpo Marx, Harpo Speaks! (New York: B. Geis Associates, 1961).

Full Name

Samuel Blair Mertes

Born

August 6, 1872 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

March 11, 1945 at Villa Grande, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.