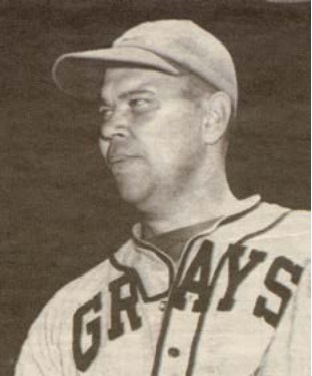

Ted Alexander

Ted “Red” Alexander was born Theodore Roosevelt Alexander in Spartanburg, South Carolina, on September 15, 1912. His parents, Joseph (b. ~1871) and Lela (b. ~1875), were farmers. According to census records, Theodore was still there in 1930, the year he turned 18. It is probably safe to assume that he was a talented young ballplayer both before and after that year, but no proof of that exists until 1936, when Alexander began his professional baseball career with the Miami Clowns; the following season, he moved halfway across the United States to play for Chicago’s Palmer House Stars.1

Ted “Red” Alexander was born Theodore Roosevelt Alexander in Spartanburg, South Carolina, on September 15, 1912. His parents, Joseph (b. ~1871) and Lela (b. ~1875), were farmers. According to census records, Theodore was still there in 1930, the year he turned 18. It is probably safe to assume that he was a talented young ballplayer both before and after that year, but no proof of that exists until 1936, when Alexander began his professional baseball career with the Miami Clowns; the following season, he moved halfway across the United States to play for Chicago’s Palmer House Stars.1

Alexander stayed on the move, spending 1938 with the Negro American League’s Indianapolis ABC’s and at least part of 1939 with the barnstorming Satchel Paige’s All-Stars, a “B team” of the Kansas City Monarchs. Paige, who had been injured, wasn’t deemed healthy enough to pitch for the real Monarchs, but was still a big drawing card, and his “Baby Monarchs” spent most of their time touring the western part of America.2 Alexander had a front-row seat as Paige somehow recovered from his injury to pitch brilliantly for another 20-plus years.

According to historian James A. Riley – who describes the 5-foot-10 right-hander as “an average pitcher with the standard three-pitch (fastball, curve, and change of pace) repertory”3 – Alexander also pitched for the New York Black Yankees in 1939, the Cleveland Bears in 1939 and 1940, and perhaps the Newark Eagles as well; however, no statistics are available from his stints with those clubs. He pitched for the Chicago American Giants in 1941, but neither Riley nor any other reference has anything to say about Alexander’s work in 1942.

In 1943 and 1944 Alexander, now in his early 30s, finally pitched for the big-league Kansas City Monarchs. There was a war on, of course, and in 1944 Alexander found himself in the US Army. More specifically, for at least a spell he was stationed at Camp Breckenridge, Kentucky, where a chance meeting with a young black lieutenant who was waiting for his medical discharge might well be responsible for having utterly changed the course of baseball history.

It is a story that Jackie Robinson would tell, albeit with slightly different details, in both of his post-career memoirs. In the earlier version, from 1960, Robinson recalled:

“I was walking across the camp recreation field when a baseball arched high into the sky and was carried toward me by a strong breeze. As it hit the ground and bounced toward me I leaned over and scooped it up with one hand. I saw a player running in my direction so I pegged a perfect strike to him. As it plopped into his glove he shouted, ‘Nice throw!’ ”

After watching for a bit, Robinson struck up a conversation with the player, complimenting him on his curveballs. “He said he had heard of me as a football player and a track man,” Robinson recalled, “but not as a baseball player. Then he explained that he pitched for the Kansas City Monarchs … and that the team needed good players. He suggested that I write if I thought I could make the grade. I wrote.”4

Robinson did not identify this Monarchs pitcher in 1960. But in his later autobiography, published in 1972, he identified him as “a brother named Alexander.”5

Considering that baseball was not considered one of Jackie’s best sports – a big star in both football and basketball at UCLA, he’d batted just .097 in his only baseball season, way back in 1940 – it was hardly inevitable that Robinson would one day find his place in professional baseball. In fact, if his memoir is to be believed, it seems highly likely that major-league history would today look quite a bit different, absent that chance meeting at Fort Breckenridge.

Meanwhile, Alexander’s biggest chance might have come in the fall of 1946 – at roughly the same moment that Robinson’s Montreal Royals were winning the Little World Series – when his Monarchs squared off against the Newark Eagles in black baseball’s World Series. Between them, the two powerhouse squads featured four future Hall of Famers in Satchel Paige, Monte Irvin, Larry Doby, and Leon Day; plus three future major leaguers, Willard Brown, Hank Thompson, and Connie Johnson. All those stars attracted the scouts, but Alexander garnered attention, too, as he started Game Four in Kansas City. It was not a stellar outing, and he gave way to Paige in the top of the sixth, trailing 4-1 in what would become an 8-1 Monarchs loss. Alexander pitched better out of the bullpen in Game Six, though that contest resulted in another Kansas City loss by a 9-7 score. Newark ended up taking the championship in a hard-fought seven-game series.

Alexander returned to the Monarchs in 1947, but the following season he joined the Homestead Grays. In the fall of 1948 he was back in the Negro League World Series, as the Grays squared off against the Birmingham Black Barons for black baseball’s championship for the third time in six years. Alexander earned the win as the Grays triumphed, 3-2, in Game One in Kansas City. In Game Three, however, he was victimized by 17-year-old Willie Mays in Homestead’s only loss in the series, at Birmingham’s Rickwood Field. With the game tied, 3-3, in the bottom of the ninth, Alexander retired Birmingham’s leadoff batter, Jim Zapp, but then surrendered a single to relief pitcher Bill Greason. He then induced a fly out from Artie Wilson but walked the fourth batter of the inning, Johnny Britton. Up to the plate came Mays, who “hit through Alexander’s legs to centerfield,” driving home Greason with the winning run.6 Though Alexander took the loss in Game Three, he and the Grays earned the championship as they topped the Black Barons in five games. That winter the Negro National League folded, which left the Grays to operate as an independent, barnstorming club.

After the demise of the NNL, Alexander played for at least four different teams in 1949, eventually ending up as a member of the barnstorming New Orleans Creoles. His itinerant existence continued when he went north in 1950 to ply his trade in Canada with the London Majors of Ontario’s Intercounty League. Alexander, who was listed at 185 pounds at the outset of his career, now weighed 220, which created an unusual dilemma as he began the season in London. According to the team’s manager, Dan Mendham, “He was real heavy and the Majors didn’t have a uniform big enough to fit him. That’s why he started the season in his Homestead Grays outfit.”7

Alexander spent all of 1950 with the majors and returned to the team in 1951; the highlight of second season in Canada was a 10-inning, two-hit shutout he pitched in London’s 1-0 victory over Guelph.8 After a brief stint with the Brandon Greys of the ManDak League in 1952, his baseball career was over.

According to his obituary, in the late ’40s Alexander began to work at Electric Boat in Groton, Connecticut, as a “submarine technician,” and retired from the company in 1977.9 He later lived in Perth Amboy, New Jersey, and East Orange, New Jersey, where he died on March 6, 1999, at the age of 86. He is buried in the Brooklyn C.M.E. Church Cemetery in Chesnee, South Carolina.

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2009), 16.

2 Larry Lester and Sammy J. Miller, Black Baseball in Kansas City (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2000), 42.

3 James A. Riley, The Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 1994), 29.

4 Carl T. Rowan with Jack R. Robinson, Wait Till Next Year: The Life Story of Jackie Robinson (New York: Random House, 1960), 93-94.

5 Jackie Robinson as told to Alfred Duckett, I Never Had It Made (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1972), 35.

6 “Grays Hold 3-1 Lead in Series,” Afro-American, October 8, 1948: 8.

7 Swanton and Mah, 16.

8 Ibid.

9 The obituary is unfortunately from an unknown newspaper.

Full Name

Theodore Roosevelt Alexander

Born

September 15, 1912 at Spartanburg, SC (US)

Died

March 6, 1999 at East Orange, NJ (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.