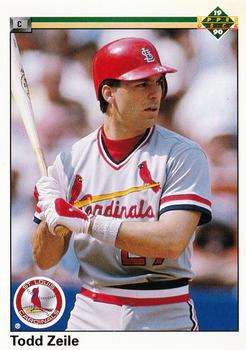

Todd Zeile

In a 16-year career marked by steady production, Todd Zeile was literally all over the place. He was traded five times, released once, and signed five separate free-agent contracts, toiling for 11 different organizations: Cardinals, Cubs, Phillies, Orioles, Dodgers, Marlins, Rangers, Mets, Rockies, Yankees, Expos, and Mets again.

In a 16-year career marked by steady production, Todd Zeile was literally all over the place. He was traded five times, released once, and signed five separate free-agent contracts, toiling for 11 different organizations: Cardinals, Cubs, Phillies, Orioles, Dodgers, Marlins, Rangers, Mets, Rockies, Yankees, Expos, and Mets again.

Ironically it was Zeile’s very dependability — production that was always pretty good if rarely at the level of superstar peers, along with a practical and professional on-field demeanor hardened by his firsthand experience of baseball as a business — that turned him into the peripatetic icon of his era: You always knew what you were getting with Todd Zeile. When it was all over in 2004, he’d crafted an odd legacy: Of the 97 players in the All-Star Game era to have amassed both 2,000 hits and 250 home runs, Zeile was the only of them never to have been named to an All-Star team.1

His frequent travels, Zeile once said, left him with “one degree of separation from everybody,”2 including contacts in Hollywood that helped him launch a post-career endeavor as an entertainment magnate and a baseball broadcaster, among other efforts in business. His itinerant baseball career and the highlights he witnessed along the way led Joe Torre to describe Zeile as “the Forrest Gump of baseball,”3 though a movie about his career might be titled Have Bat, Will Travel.

Todd Edward Zeile was born in Van Nuys, California, on September 9, 1965. For his father, Frank Todd Zeile, who also went by the name Todd, it must have a doubly joyous occasion. That night, 17 miles away in Dodger Stadium, Sandy Koufax threw a perfect game to defeat the Chicago Cubs, 1-0.

Todd Zeile was a big Dodgers fan who professed to have been in attendance at the first game at Dodger Stadium in 1962,4 and had been an accomplished semipro pitcher and infielder playing around the San Fernando Valley in the late 1950s and early 1960s. He had overcome what his son later called “a difficult childhood”5 which had included a stint living in his car. He was a high-school dropout who nevertheless rose to head an aeronautics company that developed flight systems, and was an “inspiration” to his son.6

Todd’s mother, Sammee (Spooner) Zeile, was an editor at a local newspaper. Todd was their second and youngest child; a brother, Michael, had been born 14 months earlier, in July of 1964.

The Zeile brothers were both good athletes who were baseball teammates at Hart High in Santa Clarita, California. With Mike in the outfield and Todd behind the plate, the Indians advanced to the final game of the 1982 California Interscholastic Federation Class 2-A playoffs, but lost 1-0 to Norwalk High. A teammate, Mike Halcovich, said Hart would have won the game were it played anywhere else but at Dodger Stadium, where dimensions were just large enough to contain a long drive by Todd Zeile, who was a junior that year.7

The following year, Zeile batted .520 for Hart and was a first team all-CIF selection. The Kansas City Royals selected him in the 13th round of the June draft that summer, but he chose to attend UCLA on a baseball scholarship.

The Bruins went 39-21 and won the Pacific 10 Southern Division title in 1986 behind a hard-hitting team that included future big leaguers Zeile, Jeff Conine, Torey Lovullo, and Tony Scruggs. Zeile, then a junior at UCLA, was the first of nine players from that squad selected in the June amateur draft, picked by the St. Louis Cardinals 55th overall, a second-round supplemental pick for having lost free agent Ivan DeJesus. Zeile was signed by scout Marty Keough, and began his pro career that summer for the Erie Cardinals of the short-season New York-Penn League, for whom he hit 14 home runs and drove in 63 runs, both club highs.

A steady ascent continued in 1987 with Springfield of the Class-A Midwest League, where Zeile hit .292 with 25 home runs and 106 RBIs, earning the league’s co-MVP honors with Greg Vaughn of the Beloit Brewers. Zeile also blasted two home runs in the circuit’s all-star game, marking him for future stardom.

“We’ve had some great catchers through the years but I think Zeile is going to make you forget all of them,” Cardinals director of player development Lee Thomas said that summer.8

Exploits as a minor-league slugger were one thing; Zeile’s star was also rising by association. He’d met the noted US Olympic gymnast Julianne McNamara when they were classmates at UCLA. They married in 1989, months before Zeile would make his big-league debut.

A broken thumb suffered playing winter ball in the Dominican Republic delayed Zeile’s start to the 1988 season but once healed he hit 19 home runs for Double-A Arkansas. He hit another 19 for Triple-A Louisville in 1989 when he was called up to the major leagues for the first time on August 16, swapping teams with reserve infielder Jim Lindeman.

Zeile’s major-league debut came during a doubleheader at Cincinnati’s Riverfront Stadium on August 18. He pinch-hit for Dan Quisenberry in the eighth inning of the first game and grounded out against the Reds’ Tom Browning. He started the second game behind the plate for the Cardinals, collecting his first and second major-league hits. Before the Cardinals left Cincinnati, Zeile had connected for his first big-league home run, a solo line shot to left off the Reds’ Tim Leary on August 20.

A right-handed batter and thrower, Zeile was listed at a solid 6-feet-1 and 190 pounds. He stood upright, still, and relaxed in the batter’s box — a style he said he patterned after his boyhood idol, Steve Garvey of the Dodgers.9 Unlike Garvey, Zeile tended to step toward third base when he swung, opening up and facing the pitcher directly upon contact. He maintained a grip on the bat with both hands all the way around his left shoulder and back down again, providing a hacking lift on balls he frequently drove to left and left-center.

Veteran Tony Peña, a 1989 All-Star, was the Cardinals’ regular catcher when Zeile arrived, backed up by a young defensive specialist, Tom Pagnozzi. The Cardinals let Peña go over the offseason with the idea of giving the catching job to Zeile full-time in 1990. He was also looked at as a major means of improving a St. Louis offense that was near the bottom in runs scored in ’89. The team made no major personnel moves that offseason. “Zeile’s RBI potential is a soothing tonic to the Cards’ fruitless offseason efforts to put more meat in the bat rack,” Dan O’Neill of the St. Louis Post-Dispatch wrote prior to the season.10

Cardinals fans of 1990 were, however, left asking, “Where’s the beef?” Zeile hit 15 home runs as a rookie — but that total led the team as it sputtered to a 70-92 season and last place, 25 games behind the NL East-winning Pirates. Manager Whitey Herzog, in his 11th season in St. Louis, resigned in disgust in early July, with Red Schoendienst serving briefly as interim manager and Joe Torre arriving in August.

The pairing of Torre and Zeile was a fateful one. Torre in his playing days was a one-time Cardinals catcher who turned into a star after becoming a third baseman, and he proposed the same transition for Zeile. Pagnozzi was the Cards’ starting catcher and Zeile the regular third baseman, beginning in 1991.

The transition wasn’t easy for Zeile, who would lead National League third basemen with 25 errors in 1991, while teammate Pagnozzi won a Gold Glove. Moreover, Zeile was still adjusting to big-league pitching and the prospect of being a power hitter in spacious Busch Stadium. But it wasn’t a bad year overall. Honing a line-drive approach, Zeile upped his batting average from .244 to .280 in ’91, though he hit just 11 home runs — again enough to lead a power-starved club, which in the first full season under Torre rebounded to an 81-81 record.

The Cardinals moved the fences in at Busch Stadium for the 1992 season but the change didn’t help Zeile, who suffered through a disappointing campaign (.257, 7 home runs, 48 RBIs in 548 plate appearances) that included a short hospitalization for taking a bad hop off his face and a demotion to Louisville in August. “Our priority is really to salvage the end of this year for him,” Torre said. “I told him he needs to get away from the fishbowl.”11 In the meantime, hitting coach Don Baylor criticized Zeile for a seeming indifference to the situation: Despite his struggles, Baylor said, Zeile never asked for help.12

When he got off to a slow start again in 1993, talk had begun about sitting Zeile in favor of reserve Stan Royer,13 but Zeile caught fire just in time, hitting 14 of his 17 home runs after the All-Star break and finishing with a .277 batting average and a career-high 103 RBIs. It was the Cardinals’ first 100-RBI season by a third baseman since Torre drove in 137 in 1971.

Zeile was careful not to take a victory lap, professing a pride in keeping emotions in check whether he was succeeding or struggling — a stance that occasionally would be interpreted as aloofness. His clean-shaven fastidiousness made him something of an oddball amid the prevailing dirtbag culture of his era. “He’s a good kid, he really is,” Herzog told the Los Angeles Times in 1997. “But he’s so damn laid back. We used to try to get him more fiery. We wanted him to throw helmets, cuss after he struck out, pump his fist, damn near anything to show emotion. But I’ll tell you what, he wouldn’t change. … You aren’t going to change Todd Zeile.”14

Zeile had a stressful 1994 on and off the field. In January, the Northridge earthquake badly damaged Todd and Julianne’s home in Valencia, forcing them and 6-week-old son Garrett to move in with Julianne’s parents. “Basically, the epicenter was right in our backyard,” he said.15 Young Garrett was then hospitalized for a week with a serious respiratory illness.16

In February, Zeile lost a salary arbitration hearing with the Cardinals in which he said the club made its case behind his defensive struggles at third base. For Zeile, it was hard not to be sore: feeling as though he reluctantly made the move to third base for the good of the team, only to be punished for it personally. “When I was at the arbitration hearing,” he recalled, “I listened to them rag me about my defense up hill and down dale.”17

On the field, Zeile set a career high with 19 home runs that would have been more were it not for the strike beginning in August that wound up ending the season prematurely. As the Cardinals’ player representative, Zeile helped to make that tough call. “I was a little leaguer. I wanted to see baseball too,” Zeile said in a message of sympathy to young fans when the strike hit. “But baseball is a business based on confrontations.”18

Zeile’s aloofness was likely on general manager Walt Jocketty’s mind when Zeile was abruptly traded to the Chicago Cubs on June 17, 1995 — hours before Jocketty also fired Torre in an extraordinary midseason reset. The Cardinals don’t often trade their favorite sons to the rival Cubs, but Zeile’s contention that St. Louis had withdrawn a contract extension offer after he’d injured a thumb in spring training — a matter of dispute with the front office — seemed to invite such a response.

“We’re not happy with the chemistry and focus of this team,” Jocketty said at the time. “If you saw Todd Zeile play, you could see he’s not a real aggressive person in his approach to the game. He was kind of at one gait.

“Todd Zeile was not happy here,” he added. “We didn’t want someone here who wasn’t happy.”19

The trade — Zeile for veteran starter Mike Morgan, plus minor leaguers Francisco Morales and Paul Torres — was hardly consequential for either side. Zeile, who struggled with recurring hand injuries that year, hit just .227 with a paltry .271 on-base percentage over 325 plate appearances with Chicago. The Cubs failed to offer Zeile a 1996 contract, making him a free agent. Morgan, who was also a free-agent-to-be, was re-signed by St. Louis, but released midway through a mediocre ’96 campaign.

Lee Thomas, who as a Cardinals executive had raved about Zeile as a youngster, was quick to scoop him up again, this time as the general manager of the rebuilding Philadelphia Phillies. Playing with a $2.5 million, one-year contract, Zeile banged out 25 home runs and drove in 99 runs that season, although it didn’t all come for Philadelphia: With the Phillies hopelessly out of the race and Baltimore pushing for the postseason, Zeile and fellow veteran Pete Incaviglia were dealt to the Orioles in late August for fringe pitchers Garrett Stephenson and Calvin Maduro.

The trade allowed Zeile to log a major-league best 163 regular-season games that year — plus nine additional games during his first trip to the postseason, as the Orioles (88-74) won the American League wild-card slot and knocked off the Central Division-winning Cleveland Indians, three games to one, in the Division Series. In a hard-fought ALCS vs. the New York Yankees, Zeile hit .364 with three home runs, but the Orioles fell to the eventual World Series-winning Yankees, four games to one.

The ’96 ALCS marked the first of four postseason series vs. the late ’90s Yankees juggernaut in which Zeile was a losing combatant: His clubs (the 1998 and 1999 Texas Rangers and the 2000 New York Mets) also met their ends at the hands of the Yankees in the postseason. The Yankees were world champions in each of those years.

Success on a one-year deal in 1996 did what it was supposed to and gave Zeile new possibilities as 1997 approached. Ultimately, he got that and more: a chance to return home to Los Angeles and play for his boyhood rooting interest, the Dodgers. The deal was for three years and $10 million — figures Zeile later described as a hometown discount.

“Honestly, if you go back in the 100-year history of the Dodgers, there was a revolving door at third base,” Fred Claire, Dodgers executive vice president, said. “Hopefully now we have the guy to stop that traffic.”20

That of course turned out to be wishful thinking. After a productive 1997 — cracking a career-best 31 home runs, and knocking in 90 runs for a Dodger teams that would fall short by two games to the worst-to-first Giants in the NL West — Zeile in 1998 found himself repeating his 1995 scenario all over again: traded in midseason amid an unresolved contract dispute. Only this time, the contract in question wasn’t his.

The Mike Piazza trade shook baseball, up to and including Todd Zeile. Unhappy that the homegrown future Hall of Famer — who could become a free agent after the ’97 season — had spurned the club’s offer of a contract extension and was thought to be holding out for a $100 million deal, the Dodgers under President Bob Graziano initiated trade talks with the Florida Marlins, which then were in the midst of a massive teardown. The deal — then the most expensive in terms of swapped contracts in baseball history — sent Piazza and Zeile to Florida in exchange for Gary Sheffield, Bobby Bonilla, Charles Johnson, Jim Eisenreich, and Manuel Barrios.

The trade came with implicit understanding that Florida would make subsequent deals for its new arrivals.

Naturally, Zeile had just put down roots, moving his young family — which by this time included wife Julianne and two young children — to a new home in Westlake Village.21 He didn’t shop for real estate in South Beach, but Zeile hit well in Florida — .291/.374/.427 over 270 plate appearances and was on the move again at the July trade deadline, swapped to the Texas Rangers for minor leaguers Dan DeYoung and Jose Santos, neither of whom ever reached the big leagues.

The trade not only elevated Zeile 32 games in the standings, it averted a promise to his Marlins teammates that he’d dye his hair blond if he were still in Miami after the trade deadline.22 The Rangers made room for Zeile by dispatching their current third baseman, Fernando Tatis, in a separate trade the same day to St. Louis for Royce Clayton and Todd Stottlemyre. All three new additions contributed as Texas prevailed in a season-long wrestling match for the AL West title with the Angels, who stood pat at the deadline.

Zeile made it through the entire 1999 season with the Rangers — a 95-win season marking their second consecutive division crown — playing 156 games, with 41 doubles, 24 home runs, 98 RBIs, and a career-best .293 batting average. But Texas scored just one run over the course of a three-game sweep at the hands of the Yankees in the Division Series. (Zeile’s one-time trade counterpart, Mike Morgan, now playing with his seventh club, was a Rangers teammate that year. Morgan eventually became the first player ever to toil for 12 different teams, briefly holding the all-time record now belonging to Octavio Dotel, who had 13 different employers.)

Once again a free agent, Zeile said he hoped for a return to Los Angeles but wound up choosing between offers from Texas and the New York Mets. The Mets’ winning offer of three years and $18 million came with the understanding that Zeile would have to move across the diamond to first base, where the Mets were seeking a successor to departed free agent John Olerud. Zeile through that point in his career had appeared at first base 76 times.

Zeile lacked the sex appeal New Yorkers like in their free agents and was replacing a wildly popular and productive figure in Olerud, but he ultimately proved up to the task. He was not only adequate defensively but turned in Zeile-like offensive numbers (.268/.356/.467, 22 home runs, 79 RBIs, in 153 games) that helped the Mets (94-68) earn the NL wild card, then march into the World Series, Zeile’s first and only fall classic as player.

Zeile had an outstanding postseason for the 2000 Mets. He drove in eight runs in the club’s five-game victory over his former St. Louis club in the NLCS, and was the Mets’ most productive hitter in the Subway Series, but was also an unlucky participant in what many observers consider to be the Series’ pivotal play. In the sixth inning of a scoreless Game One, with two out and Timo Perez on first, Zeile blasted a long drive off Yankees starter Andy Pettitte. The ball bounced off the padding at the very top of Yankee Stadium’s left-field wall and back onto the field of play.

Evidently convinced the drive would clear the fence, Perez had slowed his pace between first and second base and briefly raised a fist in celebration before realizing the ball would stay in play. That momentary hesitation was just enough: left fielder Dave Justice fired in to shortstop Derek Jeter, who made an acrobatic and accurate throw from the foul line behind third base in time to catch a sliding Perez at home, turning what at best looked to be a two-run homer, or at worst an RBI double, into an inning-ending, rally-killing play. The Mets lost the game in 12 innings and a golden opportunity to gain momentum in a Series in which all five games were decided by two runs or less. Had Todd Zeile done one more push-up, Mets fans lamented, anything could have happened.

By this point in his career, Zeile appeared to have accepted his fate as a baseball wanderer. Determined to make the most of New York, he rented an apartment in Greenwich Village, made a point to see the city’s cultural attractions and often rode the 7 train to games in Flushing. “I enjoy the city. I enjoy the theater. I enjoy the museums. I enjoy the cultural diversity. It’s exactly what I hoped for.”23

The Big Apple was fun while it lasted. Battling elbow woes, Zeile saw his power numbers take a dip in 2001, and the Mets (82-80) slipped along with him to a disappointing third-place finish. In a strenuous offseason remake, New York shipped Zeile and $3 million of his $6.4 million salary to the Colorado Rockies as part of a three-team, 11-player deal that also involved the Milwaukee Brewers. Seeking more offense, the Mets weeks before had worked a trade with the Anaheim Angels for their first baseman, Mo Vaughn.

Going back across the diamond to third base, Zeile had a bit of a rebound year in Colorado, producing 18 home runs and 87 RBIs. He also made his first appearance on the mound while Colorado absorbed a 16-3 beating at the hands of the Dodgers. Throwing mostly knuckleballs, Zeile gave up a leadoff single to Cesar Izturis but induced Chad Kreuter to ground into a double play and then struck out Wilkin Ruan. (Zeile put his career 0.00 ERA on the line two years later as a member of the Mets but coughed up five runs on four hits and two walks in a 19-10 Mets loss in Montreal.)

In 2003, Zeile joined the ranks of his postseason nemesis and former manager Joe Torre as a member of Yankees, but at age 37, didn’t take well to the reserve role he was offered. Platooning at first base, third base, and designated hitter with his 2000 Mets teammate, Robin Ventura, Zeile was hitting only .210 when he asked for his release in August. He was subsequently signed by the Montreal Expos, his 11th team, days later and logged his 2,000th major-league game for them while providing right-handed reserve strength.

The Mets re-signed Zeile for what turned out to be his final season in 2004. Mostly in a reserve role for a team that finished a disappointing 20 games under .500, Zeile managed to reach, then surpass, milestones of 250 home runs and 2,000 hits that year. He had already announced he would retire prior to the final game of the season, on October 3. That game was also the last in history for the Montreal Expos, who would relocate to Washington in 2005, and the final game in the Mets’ managerial career of Art Howe, who already had been informed his contract wouldn’t be renewed. But the day belonged to Zeile.

In the bottom of the sixth inning, Zeile reached for a high delivery from Claudio Vargas and lined it over the fence in left for a three-run homer in what would turn out to be his final big-league at-bat. Zeile at his own request had started the game behind the plate — his first stint catching since 1990, going out as he went in.

During a road trip in Los Angeles during that 2004 season, the normally clean-shaven Zeile sported the beginnings of hefty beard. That’s because he used the visit to Hollywood to shoot scenes in a movie in which he made an appearance as a drifter. The film, titled Dirty Deeds and released in 2005, was the debut production of Zeile’s Green Diamond Entertainment, which counted among its investors Zeile’s former teammates Jason Giambi, Mike Piazza, Tom Glavine, Al Leiter, and Cliff Floyd.24

The R-rated teen comedy was savaged by critics and Zeile reportedly lost millions in the endeavor. “It was a great education but a costly one,” he said. “I lost more than I would have paid in tuition if I’d gone to film school for 10 years.”25

In Hollywood, as in baseball, Zeile’s slumps didn’t last forever. He’d struck up a friendship with actor Charlie Sheen — they’d met in Dodger Stadium in 1997 — and Zeile had considerably better success producing Sheen’s comedy television series Anger Management.

Anger Management grew out of Zeile’s pitch to Sheen to make a show about a baseball player adjusting to a post-baseball life — although Sheen played the lead role of Charlie Goodson against Zeile’s type — beset by a bad temper.

Zeile maintained a close friendship with Sheen even as the actor endured a turbulent personal life that spilled into the public arena, resulting in Sheen’s high-profile termination from the hit television program Two and a Half Men. One way they connected, Zeile said, was through baseball.

“I was kind of in the eye of the storm and try sic to be a stable force in Charlie’s life that was going like a tornado around us,” Zeile told the New York Post. “I would try and clear his mind by taking him to batting practice and going to big-league parks. It was an outlet for him. He’s a baseball fanatic and a very knowledgeable baseball fan.”26

Zeile said he had maintained an interest in movies and entertainment since childhood — his favorite baseball movie is The Natural — and launched his production career with the help of Bill Civitella, a Hollywood talent manager who was also Zeile’s neighbor in Westlake Village.27

In addition to Dirty Deeds, Zeile produced or co-produced I Am, a movie about the Ten Commandments released to video in 2010; as well as the Comedy Central Roast of Charlie Sheen; three seasons of Anger Management, which aired on FX from 2012-2014; a comedy video called Lip Service; and The Miracle of San Quentin, a movie in production as of 2017. Zeile’s acting credits include two appearances on the TV comedy The King of Queens, and he was one of several major leaguers to play themselves in a 1997 Saturday Night Live sketch.28

Zeile, whose marriage to Julianne McNamara ended in divorce in 2015, retained an entertainment connection as a recurring analyst on SNY, the Mets’ television network, as well as the MLB Network. The father of four can also watch his daughter Hannah perform as Kate Pearson on the NBC series This Is Us (in its second season in 2017), his son Garrett on stage as a musician, and his nephew Shane Zeile, his brother Mike’s son, play outfield in the Detroit Tigers organization, which drafted Shane out of UCLA in 2014. Zeile’s other ventures include investments in a charter-jet business aimed at athletes, a role as chief business development officer at a sports video game firm called Bit Fry Game Studios, and work on the board of the Juvenile Diabetes Association.

Last revised: March 1, 2018

Photo credit

Todd Zeile, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Christina Kahrl, “The All-Star Game’s Uninvited,” ESPN.com, July 5, 2011. https://espn.com/blog/sweetspot/post/_/id/13274/the-uninvited.

2 “Exclusive Interview: Todd Zeile,” Bleeding Yankee Blue, September 19, 2011. https://bleedingyankeeblue.blogspot.com/2011/09/exclusive-interview-todd-zeile.html.

3 Albert Chen, “How Baseball Vet Todd Zeile Went From Run Producer to Movie Producer,” Sports Illustrated, July 1, 2015. https://si.com/mlb/2015/07/01/todd-zeile-hollywood-producer-charlie-sheen-profiles.

4 Bob Nightengale, “Zeile Slides Home,” Los Angeles Times, April 8, 1997: B-12.

5 Lisa Olson “Showing Zeile for the Game, and Life,” New York Daily News, March 6, 2001. https://nydailynews.com/archives/sports/showing-zeile-game-life-article-1.915650

6 Ibid.

7 Author interview with Mike Halcovich, September 19, 2017.

8 “NL East Notes,” The Sporting News, November 16, 1987: 54.

9 Zach Schonbrun, “The Batter’s Box Gets a Little Boring,” New York Times, July 21, 2016. https://nytimes.com/2016/07/24/sports/baseball/the-batters-box-gets-a-little-boring.html.

10 Dan O’Neill, “Zeile (the Baseball Card) Is Batting a Ton,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 7, 1990: 6-F.

11 George Rorrer, “Zeile Trying to Recapture His Old Zeal With Birds,” Louisville Courier-Journal, August 12, 1992: D-1.

12 Ibid.

13 Rick Hummel, “Zeile’s Recent Efforts Leave Torre Hopeful,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 20, 1993: 3-F.

14 Bob Nightengale, “Steal of a Zeile,” Los Angeles Times, February 26, 1997: C-1.

15 Dan O’Neill, “Shaken Lives: Zeiles Regroup, St. Louis Post Dispatch, January 28, 1994: D-1.

16 Ibid.

17 Rick Hummel, “Phillies Counterpunch, Sign Jefferies,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 15, 1994: D-1.

18 Mike Eisenbath, “Baseball Takes a Walk,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 13, 1994: C-1.

19 Rick Hummel, “Cards Swing 2-Edged Sword,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 17, 1995: C-1.

20 Nightengale, “Zeile Slides Home.”

21 Steve Springer, “After a Year and a Half, Zeile’s Dream Is Over,” Los Angeles Times, May 16, 1998: S-3.

22 Mike Berardino, “Zeile, Johnson Move On,” South Florida Sun Sentinel, August 1, 1998: C-1.

23 Joe LaPointe, “For Zeile, a Dream Takes on Reality,” New York Times, October 17, 2000. https://nytimes.com/2000/10/17/sports/baseball-2000-playoffs-for-zeile-a-dream-takes-on-reality.html

24 Larry Carrol, “Major Leaguers Hoping for a Home Run with ‘Dirty Deeds,’” MTV.com, August 25, 2005. https://mtv.com/news/1508378/major-leaguers-hoping-for-a-home-run-with-dirty-deeds/.

25 Chen, “How Baseball Vet Todd Zeile Went From Run Producer to Movie Producer.”

26 Justin Terranova, “Todd Zeile Went From Charlie Sheen Wingman to SNY Analyst,” New York Post, April 20, 2017. https://nypost.com/2017/04/20/todd-zeile-went-from-charlie-sheen-wingman-to-sny-analyst/.

27 Patrick Goldstein, “Exit Stadium, Enter Studio,” Los Angeles Times, June 8, 2004: E-1.

28 Internet Movie Database, https://imdb.com/name/nm1156788/.

Full Name

Todd Edward Zeile

Born

September 9, 1965 at Van Nuys, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.