Cliff Floyd

Cliff Floyd spent 17 years (1993-2009) in the major leagues and played for seven different teams, including the 1997 World Series champion Florida Marlins. Primarily a left fielder after breaking in as a first baseman, he regularly showed tremendous power and speed, placing himself amongst the best players of his time. But injuries regularly interrupted those bursts of greatness, preventing him from consistently being a major contributor to his team’s success. After he retired from playing, Floyd began a second career as a baseball analyst.

Cliff Floyd spent 17 years (1993-2009) in the major leagues and played for seven different teams, including the 1997 World Series champion Florida Marlins. Primarily a left fielder after breaking in as a first baseman, he regularly showed tremendous power and speed, placing himself amongst the best players of his time. But injuries regularly interrupted those bursts of greatness, preventing him from consistently being a major contributor to his team’s success. After he retired from playing, Floyd began a second career as a baseball analyst.

Cornelius Clifford “Cliff” Floyd Jr. was born on December 5, 1972, in Chicago. He was the first child of Cornelius Clifford “C.C.” Sr. and Olivia (Crooms) Floyd. After C.C. was discharged from the Marines, he returned to Chicago and worked overtime at the United Steel plant to support his family. When Cliff was 13, his brother Julius was born. Their mother stayed at home to raise them. Shortly after Floyd entered professional baseball, his parents adopted his sister Shanta, who was the same age as Julius.

When Cliff was 14, his father became extremely sick with kidney failure. According to an article years later in the Hackensack Record, the illness came quickly. A new home that the double shift hours had earned and the family had built from the ground was given back a week after the deal was complete because [C.C.] could no longer work.1

As the family prepared to take C.C. to the hospital, they received a phone call. “It was Northwestern Hospital in Chicago saying get Dad there as soon as you can. We have a kidney waiting,” Cliff recalled.2

Floyd, who was close to his father, said the illness changed his life. “This is a man who, even when he was sick, he always came to my games. There would be days when I was like, ‘I know my dad’s not coming to the game today,’ and there he was at the game. It was mind-boggling. It gives you so much perspective.”3

Floyd played three sports (baseball, football and basketball) at Thornwood High School in South Holland, Illinois. He made the All-State baseball team as a junior and senior, and won the Chicago Tribune’s 1991 Athlete of the Year Award for leading the Thunderbirds to the state championship in his final year, hitting .535 with seven homers and 71 RBIs. “I was so proud of him,” said his father. “He won every award there was to win.”4

Several colleges recruited the 6-foot-5, 220-pound Floyd, including Creighton University, then coached by future Chicago Cubs GM Jim Hendry. “You didn’t need to see much to recruit him,” said Hendry, who started his pursuit during Floyd’s junior year. “I saw him in a workout at St. Xavier College where he hit a home run into a 40-mile-an-hour wind. And he was a Division I basketball player, no question. We were going to let him play both.”5

Hendry described witnessing another display of Floyd’s skill. “At the time they had a [high school] summer league championship in Illinois at the end of July. Cliff hit a ball at North Central College that was like a 2-iron. It was no more than 12 feet off the ground when it left the infield and 12 feet off the ground when it hit a building beyond right field. I’ve never seen a ball hit on a line that far. It didn’t elevate and it didn’t sink.”6

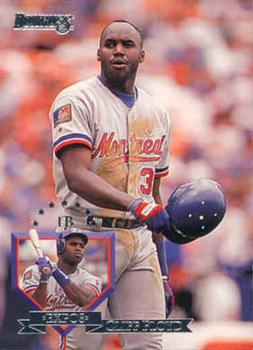

Floyd committed to Creighton, partly because his mother wanted him to attend college. But he did not expect to be picked in the first round of baseball’s amateur draft.7 The Montreal Expos surprised Floyd by selecting him 14th overall in June 1991 and offered him a $300,000 signing bonus. Hendry advised Floyd and his parents to take the money.

Floyd, a lefty hitter who threw righty, had played first base in high school, but he expected to move to the outfield in the Expos’ organization. “I know they picked me for my power,” he said. “But with my speed, I think I can find a new position in the outfield and work my way to the top.”8

He was assigned to the rookie-level Gulf Coast League Expos after signing. Still a first baseman, Floyd batted .262 with six home runs and 30 RBIs in 56 games. In 1998, Montreal assigned him to the Class A South Atlantic League. With the Albany (Georgia) Polecats, Floyd played center field and led the team with a .304 batting average. He hit for the cycle twice, led the circuit with 97 RBIs, and set a league record with 16 triples.9

Floyd continued his rise through the Expos’ farm system in 1993. He started with the Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Senators, batting .329 with 26 homers and 101 RBIs in 101 games to earn MVP honors of the Class AA Eastern League. Following a promotion to the Triple-A International League (IL), he appeared in 32 games for the Ottawa Lynx. Baseball Weekly and USA Today named Floyd the Minor League Player-of-the-Year.10

On September 18, 1993, Floyd made his major league debut, against the Phillies at Olympic Stadium. He entered the game as a first baseman in the sixth inning on a double switch and struck out in his only at-bat. Overall, he appeared in 10 games – all at first base – and batted .226 (7-for-31). His first hit was a single off the Mets’ Bobby Jones at Shea Stadium on September 24. Two days later in the same ballpark, Floyd hit his first homer, off New York’s Dave Telgheder.

Floyd was named Baseball America’s top prospect heading into 1994. But the Expos already had a trio of past or future All-Stars in their outfield – Larry Walker, Moisés Alou, and Marquis Grissom – so, Floyd was Montreal’s Opening Day first baseman. One minor league manager described him as a “Willie McCovey-type with speed” according to Gene Guidi of the Detroit Free Press.11

Floyd helped the Expos build the majors’ best record by hitting .281 with four home runs and 41 RBIs in 100 games. One of his highlights came on June 27, 1994, when he hit a three-run homer off future Hall of Famer Greg Maddux in the seventh inning to help the Expos beat the Braves, 7-2. “I phoned my dad before the game and we made a bet,” he said. “He told me to swing the bat and get a hit. I told him, ‘Nah, I’m swinging for the fences tonight.”12

The next day, however, Montreal moved Walker to first base so that his bat could remain in the lineup despite a shoulder injury. Floyd played less frequently as a consequence, and he expected to be sent back to Ottawa to keep developing his skills when major-league players went on strike in early August. When the demotion to the minors didn’t happen, he returned home to stay in shape by working out with his old high school team and “enjoying being able to sleep in my own bed again.”13

Floyd returned to first base for Montreal in 1995. On May 15, however, he suffered a fracture dislocation of his wrist, with ligament damage, in a collision with the Mets’ Todd Hundley on a play at first. “I could hear a popping sound and I could see the glove touching the back of his wrist,” said Hundley. “Unfortunately, I knew right away what happened.”14

Floyd returned to first base for Montreal in 1995. On May 15, however, he suffered a fracture dislocation of his wrist, with ligament damage, in a collision with the Mets’ Todd Hundley on a play at first. “I could hear a popping sound and I could see the glove touching the back of his wrist,” said Hundley. “Unfortunately, I knew right away what happened.”14

At the time, Floyd was hitting just hitting .176 with one homer in 18 games, but his loss was a blow to Montreal. Expos manager Felipe Alou said, “He might not be hitting right now but this was the man who solved our problems at first base. Now we don’t have him for who knows how long.”15 Floyd required surgery and missed nearly four months. When he returned to the team in September, he failed to get a hit in 17 at-bats.

In 1996, Floyd was healthy again, but trade acquisition David Segui had seized Montreal’s first base job during his absence, so he started the season as Ottawa’s left fielder. When the Expos called him up at the end of April, Alou said that Floyd would play center field for the first time since he was in the low minors four years earlier. Floyd said he was fine with the change. “I prefer it, because you don’t have to worry about the ball coming from too many different angles.”16

Floyd eventually saw most of his action in left and finished with a .242 batting average, six homers, and 26 RBIs. But he started only 47 of his 117 appearances and was primarily a reserve for the last two months of the season.

Towards the end of spring training 1997, after Floyd expressed his desire to play full time, the Expos traded him on March 26 to the Florida Marlins for Dustin Hermanson and Joe Orsulak. Later, he reflected on his years with Montreal as some of the most important of his career. “You couldn’t have asked for a better situation in terms of how they were able to find the right field coordinators, the right minor league coordinators to put all of the talent together,” he said. “The organization was great.”17 Floyd said that he grew as a person during his time with the team. “You could take some French classes and learn how to speak and understand the language. Or you could just appreciate the city itself. Montreal was great.”18

The Marlins were an improving young club that had already added the proven bats of Bobby Bonilla and Moisés Alou that offseason. “I just want to play every day,” Floyd said. “But if I can’t, I might as well be with a team as good as this one. Think all the guys (benchwarmers) on the [Chicago] Bulls complain after four [NBA] championships? I’m glad I’m here to help.”19

Marlins manager Jim Leyland did not promise to play Floyd full time. “Cliff’s a bright guy,” Leyland said. “You need 30 to 35 guys to win a pennant. I’ll play him to fill in left, center, right, and first base.”20

Floyd appeared in 61 games in 1997 and batted .234. After he injured his hamstring on June 20, he was batting only .221. Floyd was sent back to the IL to rehabilitate with the Charlotte (North Carolina) Knights. When he returned, he hit well for Florida in the final month of the season, batting .255 with four of his six homers and 14 of his 19 RBIs in 23 games to raise his average to .255. Those numbers convinced Leyland to include Floyd on the postseason roster. The Marlins finished second in the NL East but earned the Wild Card with 92 victories.

Floyd did not play in the NLDS or NLCS, but he made three pinch-hitting appearances in the World Series against Cleveland.21 He scored one run in Florida’s 14-11 win in Game Three after he was intentionally walked. Floyd won his only championship ring when the Marlins beat the Indians in seven games.

After the Marlins traded away many of their core players, Floyd got his opportunity to play every day in 1998. He assumed the team’s leadoff hitter role during spring training. “Cliff hits the hardest line drives that I’ve ever seen,” said Leyland. “I’d rather drop him down in the lineup and let him drive in some runs, but I don’t have that luxury. He’ll be a run producer at leadoff.”22

The Marlins hoped that Floyd would “reach the ceiling that all our people keep talking [about]” according to Leyland. Floyd had eight home runs with 17 RBIs by the end of April and said, “I want to have a good year. No, I want to be a little greedy – I want to be more than good. It’s kind of embarrassing after four years in the big leagues and as big as I am to only have seven (six) homers as a career high.”23

Floyd mostly batted fifth for Florida after mid-May, and he finished his best season to date with 22 home runs and 90 RBIs. His 45 doubles ranked fifth in the NL, and his 27 steals were sixth. He made all his 145 starts in left field and never played first base again.

The Marlins rewarded Floyd with a $19 million, four-year contract in January 1999. “All along we have always felt… that he had a chance to be a star in this game,” said Florida general manager Dave Dombrowski.24

But Floyd tore cartilage in his knee during spring training and was out for four weeks. Then he injured his Achilles tendon in June and missed more than two months. In all, he only appeared in 69 games, finishing with 11 home runs and 49 RBIs.

When Floyd returned to the Marlins in September, he got into a public spat with the team after manager John Boles benched him for being late to batting practice. “I’m not happy about it,” Floyd said. “I had a red-eye from Calgary. I flew at 12:30 [a.m.] and got here at 12:30 [p.m.]. I went home [to Weston] and I got a couple of hours sleep. Then I get here two minutes late. You want to scratch me for that? Fine. I feel I get no respect.”25

In 2000, Floyd bounced back from his injuries with stats that echoed his breakout 1998: .300 with 22 home runs and 91 RBIs. He also stole 24 bases, making him a threat any time that he was on base. He compiled his numbers in just 121 games after re-injuring his left knee on July 28 and missing a month following arthroscopic surgery.26 After returning to action, he hurt his wrist in September but stayed in the lineup. It was the fifth time that he had been injured in four years. When Floyd left the hospital following postseason wrist surgery, he said he hoped to return to his training regimen by the end of the year.

The following summer, Floyd addressed his injuries in an interview. “That reputation [for being soft] bothers me, but I can see where it comes from,” he said. “To me, being soft is getting hit in the elbow and leaving the game or not wanting to play [a] day game after a night game because you are tired. I don’t do that. I’m not soft. I’ve broken things like my wrist. You can’t play with things broken.”27

With his wrist healed, Floyd had his best season in 2001. He hit 31 homers, and his .317 batting average, 103 RBIs, and 123 runs scored were all career highs. He was also chosen to play in his first and only All-Star Game.28 He went 0-for-2 in the NL’s defeat at Safeco Field in Seattle.

Floyd had a strong start in 2002, hitting .287 with 18 homers and 57 RBIs during the first half. On July 11, he was traded back to the Expos – along with Wilton Guerrero, Claudio Vargas and cash – for Carl Pavano, Graeme Lloyd, Mike Mordecai, Justin Wayne, and a player to be named later. 29

“This is a great lineup, and it’s a great opportunity for myself and this team,” Floyd said after returning to Montreal. “Walking into the clubhouse today, I felt rejuvenated again. I feel like this team is ready to do something.”30

But Floyd played in just 15 games before the Expos traded him to the Boston Red Sox for pitchers Sun-Woo Kim and Seung Song. The Red Sox trailed the Yankees by five games in the AL East at the time and made the deal to boost their offense.

“It’s nice to be with a team trying to get into first place and trying to win a pennant race,” Floyd said. “My main focus is to come in and help. I’m going to play hard every single day I get out there.”31 He batted .316 with seven homers and 18 RBIs in 47 games for Boston while playing outfield and designated hitter, but the Red Sox failed to qualify for the postseason despite a 93-69 record. For three teams in 2002, Floyd batted .288 in 146 games and produced 28 homers and 79 RBIs.

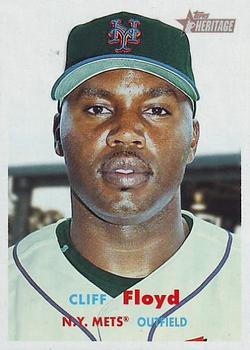

Floyd became a free agent after the season and signed a four-year, $26 million contract with the New York Mets in January 2003. Initially, he was disheartened that only a few teams were interested in him. “I never thought it would boil down to this, where it was tough to get somebody to want you,” he said. “And then this [offer] came about. I told my agent ‘You can drop everything else. You get this done.’”32

His first two years with the Mets were hampered by injuries, limiting his playing time. First, Floyd hurt his left knee in early 2003. He tried to play through the pain, saying in May, “We ain’t doing too well. You just have to suck it up.”33 He also hurt his wrist when it was hit by an errant throw during warmup.

Floyd played in 108 of New York’s first 123 games through August 18 before an Achilles tendon injury ended his season. He was batting .290 with 18 home runs and 68 RBIs. After he decided to stop playing, Floyd said “I’ve learned a lot about myself this season. I never knew that I could push myself and play through injuries like this before.” Mets manager Art Howe expressed surprise that Floyd “made it this far. But that shows he’s just a special kind of kid.”34

In 2004, Floyd hurt his elbow during spring training. Then he strained his right quadriceps in early April, causing him to miss a month. But he still managed to put up similar offensive numbers, batting .260 with 18 homers and 63 RBIs in 113 games.

Floyd’s best year with the Mets came in 2005. Healthy, he played in 150 games and led the team with his 34 home runs, his career high. His .273 batting average and 98 RBIs were second on the club behind David Wright.

The 2006 Mets led the NL with 97 regular season victories, but Floyd was limited to just 97 appearances. He sprained his ankle in June and landed on the disabled list. Then he injured his left Achilles tendon in August and missed nearly a month. Following cortisone shots, he returned in time to catch the final out of the Mets’ 4-0 victory over the Marlins on September 18 to clinch the NL East. New York swept the Dodgers in the NLDS and extended the Cardinals to the seventh game of the NLCS. Floyd batted .333 with one homer in the playoffs, but he had only 13 plate appearances due to his injured Achilles. He had surgery after the season, telling reporters “I expect a speedy recovery. I may get hurt, but I always told you guys, I heal quick.”35

Floyd became a free agent that fall, and the Mets did not pursue him, opting instead to sign Moisés Alou to play left field. Floyd was not surprised by the decision, saying “[Mets general manager Omar Minaya] has certain guys on his mind and he gets them. All I can do is thank him for four years.”36

Floyd was not a free agent for long. On January 21, 2007, the Chicago Cubs signed him to a one-year contract, prompting Floyd to say he looked forward to getting “home cooking with mom.” The Cubs general manager, Hendry, had previously recruited him for Creighton University out of high school. Hendry said Floyd “gives us a tremendous presence… and it really helps balance our left-right [lineup] combination.”37

Floyd played primarily right field for the Cubs in 2007 and largely avoided the serious injuries that had held him back in New York. He missed time in August when his father died from a stroke after years of battling kidney disease and undergoing open heart surgery.

In an open letter to fans, Floyd reflected on the last game that his father watched. “He felt better than I’ve seen him in the three weeks he was in the hospital,” Floyd wrote. “It doesn’t get any better than that. You try to play and forget everything else. When the game’s over, you go back to your normal life, knowing you got to take care of your Dad.”38

Floyd’s offensive production was down from previous years as he hit only nine home runs with 45 RBIs in 108 games. The Cubs declined to exercise their option to bring him back for 2008, preferring to rely on younger options in right field, though Hendry said he might consider signing Floyd – who turned 35 in December – as a reserve.

Instead, Floyd signed a one-year contract with the Tampa Bay Rays. He spent 2008 in a platoon role as the main designated hitter against right-handed pitchers. In 80 appearances, Floyd batted .268 with 11 home runs and 39 RBIs for the AL East champion Rays.

Tampa Bay overcame the White Sox in the ALDS and the Red Sox in the ALCS to win the first pennant in franchise history. Floyd singled and scored in Game Two of the World Series against the Phillies, but he reinjured his right shoulder and missed the final two contests as Tampa Bay fell in five games. Overall, Floyd saw action in seven of the Rays’16 postseason games, batting .222 (4-for-18) with a homer and two RBIs. He was granted free agency in November.

On February 4, 2009, Floyd signed with his final team, a one-year contract with the San Diego Padres. But he spent the first two months of the season on the disabled list after injuring his right shoulder. When Floyd was activated, Padres manager Bud Black said “He will be used as a pinch-hitter off the bench but will not play in the outfield.”39

Floyd appeared in only 10 games for the Padres; the last one on June 17, when he delivered a pinch-hit single in a loss to the Mariners. He returned to the DL shortly thereafter and was released after the season concluded. Floyd, 36, announced his retirement as a player. In 1,621 games, he batted .278 with 233 homers and 148 steals.

He began his broadcasting career in 2010, initially with Fox Sports Florida. He did well enough in that position that the national Fox Sports network took notice. Floyd joined their Baseball Night in America broadcast team in 2014.

He began his broadcasting career in 2010, initially with Fox Sports Florida. He did well enough in that position that the national Fox Sports network took notice. Floyd joined their Baseball Night in America broadcast team in 2014.

Floyd noted that former players have unique challenges as broadcasters because the current players are aware of what is said about them. “They listen and they want to be able to critique it in a way,” he explained. “Then all of a sudden (they might say) ‘hey you just said I’m adequate enough to play outfield,’” Floyd said. “What I’m basically saying is right now you’re not helping your team get to the next level. What guys forget is that I am doing my job.”40

In 2015, Floyd signed with SNY (SportsNet New York) as an analyst for Mets games. He joined Canada-based CTV Sportsnet in 2018 as a baseball analyst for their Toronto Blue Jays coverage. When Apple TV added Friday Night Baseball in 2022, Floyd became one of the three rotating analysts on their broadcasts. He also co-hosted a show on SiriusXM’s MLB Network Radio and made appearances on the MLB Network’s MLB Tonight.

Since leaving the playing field, Floyd has also been involved in other ventures. He worked with Pauze Innovations in 2010 to develop a cap liner designed to protect baseball players if they were hit in the head by a batted or thrown ball. He also started the Cliff Floyd Foundation in 2011. The organization is based in Florida and provides scholarships, financial aid, and other opportunities to students with a financial hardship.

As of 2022, Floyd lived in Florida with his wife Maryanne (Manning) and their three children: Bria Shae, Tobias Clifford, and Layla.41 The couple met when Floyd was on the Marlins and they played a series in Maryanne’s hometown of Toronto.42It was the second marriage for Floyd, who was married to Alex Floyd, a model in South Florida, from 1998-2000.43

Floyd said he was proud of his career. “I never thought I would play as long as I did. I know I could have been a helluva lot better if my body held up for sure.” He said that he understood adversity since he was hurt so often but “I dealt with them, I dealt with injuries. If there’s one thing you hear people say about me is ‘I wish he didn’t get hurt as much.’”44

Last revised: February 7, 2023

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Ray Danner.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author used the Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org websites for box score, player, team, and season pages, pitching and batting logs, and other pertinent material.

Notes

1 Steve Popper, “Floyd Finds Strength from Dad,” Hackensack (New Jersey) Record, June 17, 2006: S6.

2 Popper.

3 David O’Brien, “Cliff Climbing,” South Florida Sentinel Sun, April 4, 1999: 99.

4 O’Brien.

5 O’Brien.

6 O’Brien.

7 O’Brien.

8 Paul Sullivan, “Thornwood Slugger Floyd Top Pick of Expos,” Chicago Tribune, June 4, 1991: 41.

9 Cliff Floyd, 1993 Bowman baseball card.

10 Cliff Floyd, 1994 Collector’s Choice baseball card.

11 Gene Guidi, “The New Wave, A New Look,” Detroit Free Press, April 4, 1994: 41

12 Jeff Blair, “Floyd powers Expos to win,” Montreal Gazette, June 28, 1994: F1.

13 Associated Press, “Players Make Money Even While Striking,” Bridgewater (New Jersey) Courier News, August 30, 1994: 23.

14 Jeff Blair, “Floyd Hurt as Expos Lose,” Montreal Gazette, May 16, 1995: F1.

15 Blair, “Floyd Hurt as Expos Lose.”

16 Jeff Blair, “Floyd to Hit Out of Eighth Spot,” Montreal Gazette, April 30, 1996: D4.

17 Matt Cullen, “Former Expo Floyd Optimistic on MLB’s Return to Montreal,” TSN.ca, July 10, 2015. https://www.tsn.ca/former-expo-floyd-optimistic-on-mlb-s-return-to-montreal-1.329370

18 Cullen.

19 George Castle, “Marlins Hope Floyd Will Be Patient,” Munster (Indiana) Times, April 9, 1997: C2.

20 Castle.

21 In Game Seven, he was announced as a pinch-hitter but was replaced when Cleveland went to a left-hander. Thus, he did not make a plate appearance.

22 Dave Sheinin, “Drag Bunts or Rocket Shots,” Miami Herald, March 06, 1998: 8D.

23 Dave Sheinin, “Floyd Raises Stats, Stakes,” Miami Herald, April 27, 1998: 6D.

24 Juan Rodriguez, “Loyalty Keeps Floyd in Teal,” Florida Today, January 22, 1999: C1.

25 Mike Phillips, “Marlins Sit Angry Floyd for Tardiness,” Miami Herald, September 8, 1999: D1.

26 “Big Hurt: Floyd Out 4-6 Weeks,” Palm Beach (Florida) Post, July 30, 2000: 7C.

27 Dan Le Batard, “Marlins Floyd the Real Deal,” Miami Herald, July 19, 2001: D5.

28 His selection became the point of controversy after Floyd said that Mets manager Bobby Valentine promised to choose him a spot on the team but failed to pick him when the final rosters were announced. In the end Floyd ended up on the team when he was added as a replacement for Rick Reed.

29 The Montreal Expos sent minor league player Don Levinski to the Florida Marlins to complete the trade in August.

30 David O’Brien, “Floyd, Dempster Struggle with New Teams,” South Florida Sentinel Sun, July 13, 2002: 5C.

31 Michael Vega, “Full Fenway Fun for Floyd,” Boston Globe, August 7, 2002: F3.

32 Adam Rubin, “With Mets, Floyd Feeling Safe at Home,” New York Daily News, January 11, 2003: 50.

33 Adam Rubin, “Cliff Hangs In, Lifts Mets,” New York Daily News, May 5, 2003: 55.

34 Kevin Devaney, “Mets Floyd Headed for Season-Ending Surgery,” Poughkeepsie (New York) Journal, August 16, 2003: 5G.

35 David Lennon, “Floyd Has No Hard Feelings,” Newsday (Long Island Edition), November 22, 2006: A65.

36 Lennon.

37 Dave van Dyck, “Floyd Finally Home,” Chicago Tribune, January 25, 2007: 4-4.

38 Cliff Floyd, “Floyd Family Thanks Well-Wishers,” Munster (Indiana) Times, July 9, 2007: 35.

39 “Around the Horn (Padres Activate Floyd),” Bridgewater (New Jersey) Courier-News, May31, 2009: C7.

40 “Challenges Going from Player to Broadcaster,” Youtube.com, September 23, 2014. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eGygYrOW86o&ab_channel=SPORTSNET

41 https://www.mlb.com/player/cliff-floyd-114260

42 ”Did Cliff Floyd get married?” Live Ramp Up. September 30, 2017. https://liverampup.com/entertainment/cliff-floyd-married-wife-stats-injury-contract-salary-net-worth.html Accessed February 2, 2023.

43 Michael Bamberger. ”Cliff notes his body healthy at last and his mind clear – at least most of the time.” Sports Illustrated. August 20, 2001. https://vault.si.com/vault/2001/08/20/cliff-notes-his-body-healthy-at-last-and-his-mind-clearat-least-most-of-the-timecliff-floyd-is-having-a-career-year-for-the-resurgent-marlins Accessed February 2, 2023.

44 Steve Serby, “MLB Network’s Cliff Floyd Talks All Things New York Baseball,” New York Post.com, August 19, 2020. https://nypost.com/2020/08/19/mlb-networks-cliff-floyd-talks-all-things-new-york-baseball/

Full Name

Cornelius Clifford Floyd

Born

December 5, 1972 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.