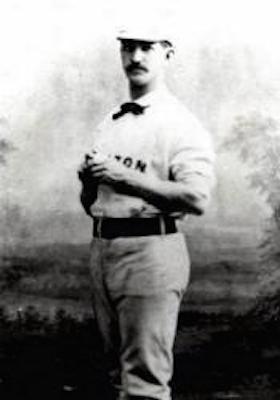

Tommy Bond

Tommy Bond was a pitching star in the infancy of professional baseball. Then batters could request a high or low pitch from an underhanded pitcher whose arm was supposed to be perpendicular to the ground. “By 1875, Hartford’s Tommy Bond was living at the edge of the rule by throwing low sidearm with tremendous speed.”1 Because the pitchers delivered from a box, which varied in size over the years, he was also able to throw plateward from a variety of angles. By the time overhand delivery became the rule; Bond had won 234 games and pitched over 3,600 innings.

Tommy Bond was a pitching star in the infancy of professional baseball. Then batters could request a high or low pitch from an underhanded pitcher whose arm was supposed to be perpendicular to the ground. “By 1875, Hartford’s Tommy Bond was living at the edge of the rule by throwing low sidearm with tremendous speed.”1 Because the pitchers delivered from a box, which varied in size over the years, he was also able to throw plateward from a variety of angles. By the time overhand delivery became the rule; Bond had won 234 games and pitched over 3,600 innings.

Thomas Henry Bond was born on April 2, 1856 in Granard, Ireland. His father, William, was English and his mother, Alicia, Irish. According to Naturalization records, the family came to the United States in June, 1862 and settled in Brooklyn.2 Like most boys of the time, Bond played sandlot baseball and was talented enough to draw attention from the better teams. In 1873 he was listed in the spring as captain of the semipro Washington Nine, but did not appear in the team’s box scores. He did play for the Brooklyn Athletics, a more prominent semipro team, in 1873.

Bond’s professional career began in 1874 with the Brooklyn Atlantics in the National Association. He got off to a triumphant start on May 5 when the Atlantics drubbed Baltimore 24-3. Bond not only pitched brilliantly, but he had two hits and scored three times. He saved his finest effort for late in the season. On October 20 he took a no-hitter into the ninth inning against the New York Mutuals. With two outs, first baseman Joe Start doubled to break up what would have been the first-ever major-league no-hitter.

The Atlantics played a 55-game schedule. Bond was the pitcher of record in every game except on July 18. The teenager toiled 497 innings to earn his 22-32 record. The squad finished in sixth place. At bat Bond hit .220, better than three position players, and his 10 doubles were tied for the team lead.

Manager Bob Ferguson moved on to the Hartford Dark Blues in 1875. Bond joined the team and shared pitching duties with Candy Cummings. Hartford finished in third place. In the box, Bond pitched in 40 games tossing 37 complete games. He had a 19-16 record with a sizzling .878 WHIP and 1.41 ERA, both the best for any pitcher with over 100 innings. In addition to his pitching duties the teenager played outfield and some infield. He took the field in 72 games and batted 289 times with a .266 average and was fifth on the team in extra-base hits.

The National Association dissolved in 1875 and was replaced by the National League. Hartford joined the new circuit and posted a 47-21 record, good for second place behind Chicago. Bond took over as the number one hurler, with Cummings acting as the change pitcher. Bond made 45 starts, all complete games, and pitched 408 innings with a .902 WHIP and 1.68 ERA. He was 31-13 with one tie. At the plate he hit .275 tying him with Jack Remsen for second on the squad.

His won-loss mark might have been more impressive had he not run into St. Louis hurler George Bradley in mid- July. Over a three-game stretch, Bradley shutout the Dark Blues and Bond three times. He furthered the insult by authoring a no-hitter in the third game on July 15. Bradley’s gem was the first no-hitter in the major leagues.

Bond might have piled up 500 innings of work had he not gotten into a disagreement with Ferguson and club management. Bond accused Ferguson of throwing a game against Boston. Director Morgan G. Bulkeley sided with Ferguson and offered $1,300 for proof that Ferguson had thrown the game. Unable to provide proof, Bond was suspended by the team. Bond issued a retraction, but the suspension was not lifted.3 Cummings, who had only worked four games through August, pitched the remaining 20 games starting September 5.

The Boston Red Stockings took advantage of the situation and signed Bond for the 1877 season. Bond was now in his physical prime and, though he stood only 5-foot-7 and weighed 160 pounds, had an excellent curveball to go with his speed. In later life he also claimed to have thrown his own version of a spitball. He claimed that he kept a wet sponge to moisten his fingers. Catcher Charley Snyder, a teammate in Boston, confirmed that with wet fingers Bond could get “a peculiar shoot on his ball.”4

Bond joined a Boston roster that included four future Hall of Famers: George and Harry Wright, Deacon White, and Jim O’Rourke. Bond pitched all but three games that season; Will White, Deacon’s brother, pitched the other three. The team took the pennant with a 42-18 mark while Bond sported a 40-17 record. Bond threw 521 innings on his way to the pitcher’s Triple Crown. He had a 2.11 ERA and 170 strikeouts. He also led the league in winning percentage and WHIP.

The 1878 season was nearly a carbon copy. Boston won the pennant with a 41-19 record. Bond pitched 532 2/3 innings, leaving a mere 11 1/3 for Jack Manning. Bond was 40-19 and led the league in strikeouts again. After batting .228 in 1877 he dropped off to .212. In both years he saw a few innings of action in the outfield. In the offseason he worked in a grocery store in Boston and quite likely started courting Louise Siebert.

The National League expanded the schedule by 40% in 1879. Boston posted a 54-30 record, but finished in second-place behind the Providence Grays. Left-hander Curry Foley was brought in to serve as change pitcher for Bond and tossed 16 complete games. This help did nothing to lighten Bond’s load. He hurled 555 1/3 innings and completed 59 of his 64 starts. This performance gave him a mind-blowing 1609 innings of work in three seasons. He also made a few appearances in the outfield and at first base, batting .241 in 70 games.

Bond wed Louise on December 12, 1879. The Sieberts were of German descent and Fred Siebert, her father, was a leather merchant in Boston. The couple moved in with her family and Bond was welcomed into the family business.

Rookie catcher Phil Powers was matched with Bond in 1880. Powers was not as skilled as Bond’s previous batterymates and it affected his performance. More importantly Bond’s arm began to give out. Manager Harry Wright slightly lessened his workload to a mere 493 innings. However Bond saw more action in the field than ever before getting 282 at-bats and hitting .220. In the box he posted a 26-29 record.

The National League lengthened the pitching distance from 45 to 50 feet in 1881. Bond’s arm was getting weaker and the added distance made for a greater struggle. After a 9-0 bludgeoning by Detroit where he surrendered 19 hits, he retired. The Cincinnati Commercial Tribune reported “that the fifty-foot rule has shelved Tommy Bond as a pitcher.”5 He joined a brother in New York in business in June, but by November had returned to Boston where he would reside until his death.

Bond worked out with the Harvard baseball team in the March, 1882. He tutored the pitchers and worked on a new delivery of his own. Encouraged by what he felt was a “new life” he signed with the Worchester Ruby Legs in the National League. Bond’s optimism proved ill-advised and he was able to throw in only two games. Unwilling to give up the dream, he played some outfield and even served as manager for six games. In June, he and first baseman Ed Cogswell both retired with lame arms. In August there were press reports that Bond would join the Louisville Eclipse of the American Association. These proved unfounded, but he did play with the Memphis Eckfords, a semipro team.

The following year Bond did not play professionally. That did not keep him off the diamond. In September umpire W.E. Furlong resigned and Bond was hired to work the last weeks of the season. His first appearance came September 3 when he worked the Boston-Providence game in Providence. For the most part, reviews of his work the rest of the season were favorable.

In 1884, Bond was approached by Harry Wright and Tim Murnane to join the Boston franchise in the new Union Association. Now 28, Bond took the box again with a new shoulder-level delivery that gave him speed and sharpened his curve. His demeanor was an early issue, the press reporting that he complained too much about trivial issues. He started 21 games and posted a 13-9 record. He also played 14 games in the field and posted a career-best .296 average with eight doubles in 162 at-bats. Bond and Boston parted ways in July and he signed with the American Association Indianapolis Hoosiers. He took the field on July 19 and dropped his first game to Toledo, 8-4. He pitched five complete games, losing them all and posting a 5.65 ERA. He wisely called an end to his career and returned to Boston.

Bond applied to be an umpire in National League in 1885 and did work games. In August, Sporting Life noted that he called more men out for failing to touch a base than any other umpire.6 The rest of his work must have been sub-par because he was replaced by John Gaffney later that month. In 1886 he returned to the field and pitched for Brockton, Massachusetts in the New England League. Sporting Life reported he won his first three games, but he was released soon after. He was a substitute umpire for the International League late that season. In the coming years he worked as an umpire in the New England leagues and on the college circuit.

At home, he and Louise would welcome three children – Helen, Edward and Fred. He worked in the Siebert family business before taking a job in the Boston Assessor’s Office. The city job lasted for 35 years until he retired. Bond became a prominent member of the Masons and the Odd Fellows.

Louise passed away in 1933. Bond later moved into his daughter’s home. His last baseball appearance was a 1936 Old-Timers gathering where, at age 80, he still played catch with teammates. On January 24, 1941 he passed away in Helen’s home. He was buried in Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston.

Notes

1 John Thorn, “Pitchers: Evolution and Revolution,” www.ourgame.mlblogs.com, August 6, 2014.

2 These same records list him with an April 2, 1854 birth.

3 “The Hartford Letter,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, September 9, 1876: 5.

4 “Curve and Spitball Theories,” Altoona Tribune, April 4, 1907: 10 and “Old Tom Bond’s “Sponge Ball”,” Pittsburgh Press, August 14, 1907: 8.

5 Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, May 26, 1881: 5.

6 Sporting Life, August 19, 1885: 5.

Full Name

Thomas Henry Bond

Born

April 2, 1856 at Granard, (Ireland)

Died

January 24, 1941 at Boston, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.