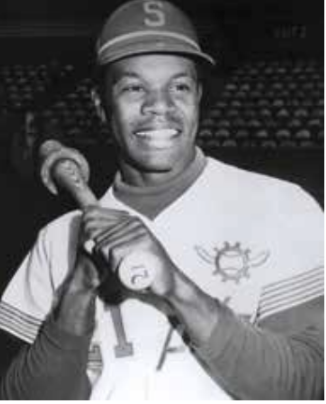

Tommy Harper

In 1970, Tommy Harper became a member of what was once among the most exclusive “clubs” in baseball. That year, his first with the Milwaukee Brewers, he hit 31 homers and stole 38 bases, thereby joining the “30-30 Club.” At the time, the only other members of the club were Hank Aaron, Bobby Bonds, Willie Mays, and Ken Williams of the 1922 St. Louis Browns.1 Baseball Digest once called the accomplishment “the most celebrated feat that can be achieved by a player who has both power and speed.”2 Harper was, not surprisingly, the MVP for the Brewers that year. Three years later, he was Boston Red Sox MVP, a year in which he stole 54 bases. His season high for stolen bases was in 1969, when he led the majors with 73 for the Seattle Pilots.

In 1970, Tommy Harper became a member of what was once among the most exclusive “clubs” in baseball. That year, his first with the Milwaukee Brewers, he hit 31 homers and stole 38 bases, thereby joining the “30-30 Club.” At the time, the only other members of the club were Hank Aaron, Bobby Bonds, Willie Mays, and Ken Williams of the 1922 St. Louis Browns.1 Baseball Digest once called the accomplishment “the most celebrated feat that can be achieved by a player who has both power and speed.”2 Harper was, not surprisingly, the MVP for the Brewers that year. Three years later, he was Boston Red Sox MVP, a year in which he stole 54 bases. His season high for stolen bases was in 1969, when he led the majors with 73 for the Seattle Pilots.

Harper’s athleticism saw him excel in many sports. He was an all-league quarterback while in high school, and was named as a guard on the All-Northern California basketball team. He ran the 100-yard dash and played baseball.3 As a student at Santa Rosa Junior College, he was all-league in three sports before he enrolled at San Francisco State. He’d turned down scholarship offers at Utah State and Washington State because he didn’t want to play football in college.4

Scout Bobby Mattick of the Cincinnati Reds signed Harper on May 28, 1960. Mattick urged him to convert from outfielder to infielder. The Reds assigned him to the Topeka Reds, their affiliate in the Class-B Three-I League.

Tommy Harper was born in Oak Grove, Louisiana, on October 14, 1940. When he was 4 years old, the family moved to Alameda, California. His father was a carpenter who gained employment in an industrial mill after the move. His mother worked at the naval air station in Alameda.

Tommy attended the public schools there, graduating from the city’s Encinal High School. He was captain of the baseball team in his senior year, captain of the football team, and captain of the basketball team for two years. He ran the 100-yard dash in 10.2 seconds. After his first year at San Francisco State, striving for a degree in physical education, Mattick signed him for Cincinnati.

After joining Topeka in 1960, Harper appeared in 79 games. He hit .254 in his first pro season, stealing 26 bases, and showed a good eye at the plate, drawing 76 walks and bumping up his on-base percentage to .429. The team, managed by Johnny Vander Meer, finished in last place.

Under Dave Bristol, Topeka finished first in 1961. Harper hit .324, with 136 bases on balls and an impressive .488 on-base percentage. Harper stole 31 bases. He led the league in runs scored with 131 and was named all-star second baseman and Three-I League MVP.

Harper made the majors in 1962, debuting at Crosley Field at third base on April 9, batting eighth in the order. He had a 1-for-4 day, his first big-league base hit coming his second time up, a single to right field on a check swing.5 Harper was right-handed, listed at 5-feet-9 and 165 pounds. He played the very next day, in Los Angeles against the Dodgers and had a 3-for-4 day with his sixth-inning single providing his first RBI and tying the game, 2-2. Over his next 16 plate appearances, Harper failed to reach base and struck out six times. “Pressure caught up with the kid,” said manager Fred Hutchinson. “He’ll find himself down at San Diego. He’s a helluva prospect.”6

On April 15, the Reds recommended that Harper spend the rest of the year in Triple-A ball with the Pacific Coast League San Diego Padres. He was among the league leaders all season long and there was some thought of bringing him up to the big-league club at the end of July, but Padres manager Don Heffner said he felt Harper would benefit from a full season at Triple A and the Reds brass concurred.7 The Padres won the PCL pennant by 12 games.

In 144 games, Harper hit for a .333 average (105 walks helped earn him a .450 on-base percentage) with 26 homers, 84 RBIs, and 120 runs scored. At the time, Regis Philbin had his own local TV show on station KOGO and Harper was his guest on the 11 P.M. show on July 14, 1962, sharing the limelight with “Giselle MacKenzie, star of Gypsy at the Circle Arts; George Pernicano, the pizza king; [and] Judi Henske folk singer.”8

Come 1963, Harper was in the majors to stay. When he returned, though, he was played in the outfield alongside Frank Robinson and Vada Pinson.9 There was anticipation and Fred Hutchinson said, “[H]e could well be our top rookie this spring.”10

Before the season began, Harper married Bonnie Jean Williams of Topeka, Kansas. Receptions were held both in Topeka and Oakland.11

He got in a pretty full season’s work, appearing in 129 games. He hit his first big-league home run on June 11 and added nine more before the season was done. He was more adept at scoring runs (67) than at driving them in (37), in part a function of leading off. With a .260 batting average and 44 walks, he had an on-base percentage of .335. Both his average and his OBP were very similar to his career finals: .257 and .338. The year 1963 was also his teammate Pete Rose’s debut year; Rose hit .273. Harper was named to the Topps Rookie All-Star Team, as was Rose.12

In 1963 Harper played right field more and in 1964 most of his games were in left, though he played in only 102 games in 1964 (.243 with an OBP of .326). Basically, he said, he was platooned, “hit mainly against left-handed pitchers who I hated to hit against. I would rather bat against right-handers any day.”13

After the 1964 season, he did a tour of reserve duty at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

When Harper finally became an everyday player, starting in 1965, he produced. He played in 159 games in 1965, almost all in left, and led the major leagues in runs scored (126, tied with Zoilo Versalles of the Twins). He hit for a .257 average, with 18 homers, and drove in 64 runs. His 35 stolen bases led the Reds. “That year was the first chance I had to play every day. I did well in ’65 and the next year I was back on the bench platooning again. It was kind of frustrating.”14

Harper must have been thinking of 1967. In 1966, reunited with Dave Bristol, who’d been his manager in Topeka, he appeared in 149 games with 621 plate appearances.15 Harper hit .278, got on base 34.8 percent of the time, and scored 85 runs. He played all three outfield positions, often moving fields during the course of the game — 92 games in right, 77 in left, and 26 in center. During the offseason, he remained in Ohio, working in Dayton’s Montgomery County Family Court Center with boys in detention aged 8-17. He taught them sports, at the e time serving as a role model.16

He’d hit four homers in 1964, 18 in 1965, and five in 1966. In mid-September of the 1965 season, Harper pleaded with a reporter not to call him a slugger. “Write about me stealing bases, or write about me beating out bunts. But, please, don’t write about me being a home-run hitter. That’s just not me. … My job is to score runs, not hit home runs.”17

In 1967 Harper was in just 103 games, batting .225. He would have played more but missed two months, from May 29 to July 26. He’d suffered a fractured right wrist on May 28 crashing into the outfield wall when chasing a foul fly in Pittsburgh. The Reds still got value for him after the season, when they traded him to the Cleveland Indians for three players — George Culver, Bob Raudman, and Fred Whitfield. It was Cleveland club President and GM Gabe Paul who acquired Harper; Paul had been Reds GM when Cincinnati first signed Harper.

Harper had already proved himself to be an excellent leadoff man, and strong on defense at more than one position — he’d been the best second baseman in the Three-I League in 1961 and the best third baseman in the PCL in 1962. He was solid as an outfielder; looking back on his career as a whole, he had a .986 fielding percentage when playing outfield. One self-criticism he voiced over the wintertime of 1967 was in regard to his throwing: “My arm isn’t as strong as maybe It should be. But I try to make up for it by getting to the ball quicker.”18

In the American League, Harper was used more often in 1968, appearing in 130 games, but batting only .217. Once more he was critical of the way he was platooned, this time by manager Al Dark.19 “It’s no secret I was unhappy in Cleveland. I was platooned too much. I don’t want to be in the lineup just because the pitcher is a lefthander. If you’re going to bench me, bench me.”20

In early October, the Indians offered Harper and four other players to the Washington Senators, hoping to acquire Frank Howard. It wasn’t enough. The Tribe left him unprotected in the 1968 expansion draft. The Seattle Pilots had first pick and selected Don Mincher. After the Kansas City Royals picked pitcher Roger Nelson, Seattle used its next pick to take Tommy Harper. Bobby Mattick, the scout who had first signed Harper, was involved in the draft, working at the time as a special assistant to Pilots GM Marvin Milkes.21

Manager Joe Schultz believed Harper had not been used to best advantage. “Under happier circumstances,” he said, “Tommy could lead the American League. Harper said that coming to Seattle was like getting a new life. He’s raring to go.”22

Schultz initially penciled in Harper to play second base for Seattle, and indeed he appeared in as many games there as he did at any other position, but he played 59 games at second and also 59 games at third base. He also played 26 games in the outfield, mostly in center.

The first game in the Pilots’ history was played in Anaheim Stadium on April 8. The first Pilot to perform for the team was their leadoff batter in the top of the first inning. Tommy Harper doubled to left field. Next up was Mike Hegan, who homered. Harper thus scored the first run in franchise history. The team’s first home game was on April 11 at Sick’s Stadium, Seattle. The first Pilot to bat in front of the home crowd was Harper, who singled to the shortstop — and then stole second base, the first home theft in franchise history. He scored later in the inning.

There were a lot of stolen bases for Harper in 1969. He stole 73 bases, 11 more than anyone else in the major leagues. It was more than double his total in any prior season. “Joe [Schultz] just told me I would run when I wanted to. It was the first time I was able to run on my own without any signs.”23 The confidence Schultz showed in him bred self-confidence in Harper.24 On May 24, he stole home. The next day, he stole three bases. “Tailwind Tommy” went on to credit Maury Wills and Lou Brock as players from whom he had learned, adding, “I was quicker than most, but I wasn’t blinding fast. The thing that helped me the most was being quick and then learning the pitchers.”25

For the only time in his career, Harper drew more walks than he struck out. He hit .235 (the Pilots’ team average was .234), with an on-base percentage of .349. He drove in 41 runs and scored 78.

Harper never played for the Pilots again. Neither did anyone else. After just one season of existence, and in financial difficulty, the team was declared bankrupt on April 1, 1970. The team relocated to Milwaukee and were named the Brewers. Harper played for the Brewers in 1970 and 1971, and the 1970 season was “my best year in baseball.”26

Dave Bristol was Harper’s manager yet again, for the Brewers in 1970 and 1971. Harper truly excelled in 1970. He hit for a .296 batting average, leading the Brewers. He led as well in home runs (31), RBIs (82), runs scored (104), and of course in stolen bases (38). There were, naturally, fewer opportunities to steal bases when one hits home runs, or for that matter, extra-base hits (Harper hit 35 doubles, up from 10 the year before.) He ranked fifth in the league in slugging. This was his 30/30 year, and he was not only named team MVP but placed sixth in league MVP balloting. He was a reserve on the American League All-Star team and entered the game as a pinch-runner for Harmon Killebrew, but was cut down trying to steal second base.

Harper said that he’d simply worked harder to prepare for the season, staying late after every game in spring training to get extra batting practice. He was learning the pitchers better, Bristol said, and become more confident. Harper said that in getting a chance to play every day he felt “more involved with the team. … I feel that winning and losing falls on me and I like that feeling.”27

In 1971, Harper struggled to get going, and as late as June 20 had rarely even reached .200 in batting average. After being moved from third base to left field, he hit .317 in July and .343 in August, winding up the ’71 season at .258. In midseason, on July 24, Rev. Jesse Jackson presented Harper with the Martin Luther King Jr. Sports Medallion co-sponsored by Coca-Cola and the local chapter of Operation Breadbasket.

The Brewers felt they needed more hitting, and worked out a 10-player trade with the Boston Red Sox, with George Scott and Billy Conigliaro as their primary targets. The October 10, 1971, deal netted Milwaukee Scott, Conigliaro, Ken Brett, Joe Lahoud, Jim Lonborg, and Don Pavletich for Harper, minor-leaguer Pat Skrable, Lew Krausse, and Marty Pattin. Harper had always hit well at Fenway, which was part of the thought process. One unnamed Red Sox official said, “We got rid of all our headaches.”28 Sox executive Dick O’Connell was quoted on the record, regarding some of the malcontents, “I’m sick of listening to some of these people.”29

More than one newspaper article said that Harper “has a reputation at a brooder.”30 And yet, it was agreed near the end of spring training, “Harper is well-liked by his new teammates.”31 Milwaukee Journal sportswriter Larry Whiteside said, “Few people know the real Tommy Harper. He’s the strong silent type, except when pressed, and prefers to let his bat and his feet do his talking.”32 Manager Eddie Kasko, who had been a teammate of Harper’s in Cincinnati, was more interested in his baseball talent. “I’m going to play him at left, center and third in spring training. If I move Yaz to first, Tommy will be my left fielder.”33 Where he played in 1972 was center field, for 143 games. Yaz stayed in left and Reggie Smith played right field. Harper roomed with Luis Tiant (15-6) when the team was on the road. Sportswriter Fred Ciampa called Harper “the most exciting player to come to the Red Sox in years.”34

Harper hit .254, with a .341 on-base percentage, and scored a team-leading 92 runs. He drove in 49. His 25 stolen bases placed him sixth in the American League. He might have attempted more steals, but Luis Aparicio batted second in the order and the pair worked on the hit-and-run more than just the straight steal. Harper also missed time to a hamstring injury in late June and a balky knee later in the season. Rick Miller often filled in for Harper in late innings.

And Harper came very close to seeing the Red Sox win the pennant. The year 1972 started late due to a work stoppage. The agreement was that when the season began belatedly, teams would play the remaining games on the schedule but not make up the games that had been lost. The Red Sox played 155 games and finished with a record of 85-70. They finished in second place, a half-game behind the 86-70 Detroit Tigers. Had the Red Sox played one more game (so that the two teams played the e number of games), and had they won that game, there would have been a tie. As it was, Detroit advanced to the playoffs. The Red Sox went home.

If 1970 was Harper’s best year, 1973 ranks second. Yaz moved to play first base, and Harper took over left field. He played in 147 games, 140 in left field. And he got in his time at the plate; only Yaz had more plate appearances. It was the first year of the designated hitter. Orlando Cepeda was Boston’s first DH and he acquitted himself very well, second only to Yastrzemski in runs batted in. It might have seemed like a role Harper, age 32, could envision for himself in 1973 or in the future. He took a wait-and-see attitude, to see how the new experiment worked out, but didn’t see it as likely to be in his future. “I do know I hit better when I’m in the ball game all the way. I’ve never been much of a pinch hitter.”35

Harper had a subpar first half, batting .216 in May and .180 in June, but then caught fire with .342 in July and .320 in August. By season’s end, he had a .281 average (.351 OBP) with 17 homers and 71 RBIs, and — most notably — 54 stolen bases. That set a Red Sox team record, not surpassed until Jacoby Ellsbury stole 70 in 2009 (with Harper’s encouragement all season long).

The Red Sox finished second yet again. After the season, Tommy Harper was named Red Sox MVP.

What might explain the ups and downs of the yearly stolen-base totals throughout his career? Or, for that matter, his home-run totals? It had to do with his approach to the game, he told the Boston Herald’s Bill Liston before the 1973 season began. Every player has a particular job to do. “When I was with Seattle, they wanted me to run. So, I ran. That’s what I was supposed to do. … I can run when I feel like it on this club. I don’t have to wait for a signal. But last year we (the Red Sox) were going more with the hit-and-run play and it was working pretty good, especially early in the season before Luis (Aparicio) got hurt. If you’re effective that way, there’s no sense in stealing.” He added, “Three years ago in Milwaukee when I hit 31 homers a lot of things just fell into place for me. I was batting third or fourth in the lineup in those days and I was expected to try to drive in a lot of runs. But that’s not my job any more. I’m just supposed to get on base and that’s all I think about now. … I just want to make a contribution. Like I said everybody has a special job to do and I’ll bust my hump doing whatever that job turns out to be.”36

In 1974, it was pretty clear that Cecil Cooper was going to make the big-league team. Where would he fit in? Would he dislodge Harper? Harper said he wished he were Pete Rose with the Reds because Rose had built a consistent record and knew where he’d be playing. “But every year I have to guess where I’ll be playing.” Red Sox manager Darrell Johnson said he’d be playing, for sure.37 But as the headline of a Peter Gammons column asked, “Yaz, Harper Sign — But to Play Where?”38 There was some thought of Harper becoming designated hitter and after Cepeda was released outright at the end of March, that’s how Harper began the season.

He got off to a bad start, hampered by a number of minor injuries and performing significantly worse than the slow start of 1973: He hit. 180 in April but only .109 in the month of May. He was still under .200 when June ended. Until mid-July, Harper was indeed the team’s DH. From then on, he primarily played left field. Without a doubt, it was a down year. appeared in only 118 games, and hit .237 (though he had a .312 on-base percentage).

The Red Sox had a number of very talented outfielders on the way up — witness the home-grown outfield they fielded in 1975: Jim Rice, Fred Lynn, and Dwight Evans. They felt they no longer needed Harper and so traded him to the California Angels on December 2 for utilityman Bob Heise, getting such value as they could. In retrospect, one can see that the Sox were well set. At the time, though, the deal prompted “derision” — trading the very popular Harper for someone most fans “had never heard of.”39

Harper had the opportunity to reinvent himself with Dick Williams’s Angels. Williams wasn’t sure at first whether he would use him as DH or outfielder.

Harper hadn’t been surprised to be traded, but it was portrayed that he’d been dumped. He didn’t want to demean Heise, but he asked, “How can you be a club’s MVP one year and not make the lineup the next?”40 Ross Newhan wrote that it was a jolt to his pride and that he resented the way the Red Sox had used him. “I don’t know why they got rid of me,” he told Dick Miller. “They could have gotten more, Evidently, I was the only one who lost it last year. I was the only one they sent away. I must have blown a seven-game lead.”41 Clearly, he was bitter. He was also ready to prove himself.

He hit consistently in 1975, starting stronger than usual but then dropping a few points each month as the season progressed. He DH’ed most of the time, but played 19 games at first base and only nine in the outfield. Harper was batting .239 on August 13, with 40 runs scored and 19 stolen bases, when the Oakland Athletics purchased his contract from the Angels. The deal was reported as being in excess of the $25,000 waiver price, but it clearly was a relatively small sum. The A’s let pitcher Jim Perry go to make room on the roster for Harper.

For Harper, it was a move to a contending club. Oakland was leading its division at the time. In a classy move, the Angels’ Mickey Rivers — who led the league with 70 stolen bases — credited Harper with helping him hone his craft.42

Harper contributed some to the A’s, and indeed saw his team go into the American League Championship Series against the Red Sox. Harper appeared only once, in Game Two. Boston had a 4-3 lead and Harper pinch-hit to lead off the top of the seventh and drew a walk, but was held to the bag, unable to steal, and then was doubled off first base on a fly ball to center field.

Harper’s last year as a player was 1976. The Athletics released him in November 1975. He got an invite from the Baltimore Orioles to spring training and made the team, signing as a free agent just as the season began, on April 9, 1976. Primarily he pinch-hit or pinch-ran, while DH’ing in 27 games. Once he played first base and once he played left field. He appeared in 46 games in all, batting .234 (.318 OBP). He stole four more bases, for a total of 408 in his career.

Harper’s last major-league game was on September 29, and he enjoyed a 3-for-5 game with two doubles and two runs batted in.

There was another expansion draft and the Seattle Mariners were one of the teams being staffed. It would have been interesting had the Mariners selected Harper as the Seattle Pilots had years earlier, but it was not to be. He was not protected by the Orioles, but he was also not selected in the draft. On December 21, the O’s placed Harper on waivers for the purpose of releasing him.

Harper was invited to join the A’s in 1977 spring training, and hit .400, but was released on March 25, a casualty of a trade that Oakland had to make involving other players.43 He took a position as a minor-league instructor and scout with the New York Yankees. That November, it was announced that Harper would take a position in the Red Sox front office working with Johnny Pesky and trainer Charley Moss selling advertising.44 In February 1978, the Red Sox announced that he would work as an administrative assistant and minor-league instructor, in uniform during spring training and then working with their farm clubs during the season and in public relations during the offseason.45 As Harper learned from a newspaper reporter, sometime after arriving to take his job, the team had listed him as their affirmative-action officer. He had no idea, and later told writer Bob Hohler, “Had I known my job would include that title, I would have stayed in New York.”46

The Massachusetts Commission Against Discrimination had its eye on the Red Sox and had termed the team’s efforts in hiring women and minorities to have been “minimal” in 1977. In May 1978, it was publicly announced that the team had assigned Harper to “oversee compliance by the team with affirmative action.”47 He had the title of assistant director of marketing and promotions and player coordinator for special events. Harper said that, as part of his job, “I deal a lot with the players and I make it my business to talk to all of them, especially the black ones. They tell me they’ve never had anybody they could sit down and talk to before.”48 Harper could share that very experience; in Winter Haven for spring training in 1972, he had found the region “so intimidating that he seldom ventured far from his room.”49 At some point, an MCAD investigator paid an unannounced compliance visit and, Harper said years later, “I told them the Red Sox were ignoring everything in the settlement. I told them it was business as usual and the Red Sox didn’t intend on hiring anyone [of color]. It was all a charade.” Though it was said to have not been known until Hohler’s article in 2014, the Sox relieved him of his affirmative-action position — but kept him on the masthead as such.50

In October 1979, the Red Sox asked Harper to join the uniformed team as first-base coach. He served in that capacity for five years, through the 1984 season, under Don Zimmer in 1980 and then Ralph Houk for the next four years.

When John McNamara was hired as Red Sox skipper to begin in 1985, Harper was brought back in to the front office and named a special assistant to new GM Lou Gorman.

In February 1985, Peter Gammons wrote that “the local Elks Club in Winter Haven gives privilege cards to the Red Sox delegation — except those who are black. Believe it or not, there is still a segregated institution in this country, so Rice, Mike Easler, Tommy Harper and others can’t eat there.”51 Harper acknowledged he’d been aware of this since 1972 when he asked Reggie Smith about the cards that the white players received but black players did not. Michael Madden said that some on the Red Sox saw this as “much ado about nothing,” quoting Haywood Sullivan as saying, “There’s nothing wrong, and there has been nothing wrong.” Lou Gorman, however, promptly said the Red Sox would have “no further connection with the Elks Lodge and that he would personally rip up all the Elks passes on the team’s premises.”52

Harper recalled an incident when he was with the Brewers in 1970; at that time, the team as a whole decided not to attend a welcoming luncheon to which the team’s black players had not been invited. That had not happened with the Red Sox — and Jim Rice was quoted as saying it didn’t really bother him because he didn’t want to go there anyhow. Harper said it was a matter of principle.53

That December, Harper lost his job. Madden basically blamed Haywood Sullivan, noting that Gorman worked for Sullivan. He wrote, “Harper spoke out only because he was most loyal to the Boston Red Sox, he was so loyal that he would risk his own career so that perhaps the Red Sox might see the light. Harper’s loyalty was most basic, that no organization could ever succeed if it treats white people with more preference than blacks or Hispanics.”54

On January 30, Harper filed a formal complaint of race discrimination with the US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. “I’m not here to be a hero,” he said. “I’m not out to get the Red Sox. What the Red Sox did was wrong and demeaning. … The only reason I’m here is to retain my job, maintain my dignity and end all the whispering and reasons the Red Sox had given for my firing.”55 He said he’d been ostracized by the team after the newspaper articles in March and given no work assignments.

Globe columnist Will McDonough, often seen as a mouthpiece for management, suggested in an aggressive column that perhaps it was that Harper had been brought into the organization by Buddy LeRoux, and now found himself on the outs due to the political infighting that had pushed out LeRoux.56

Harper sat at home in Stoughton, Massachusetts, for a half a year without a job until he found a position working at an auto-body shop just 200 yards from Fenway Park. In July 1986, the EEOC found that the Red Sox “committed unlawful employment practices” by firing Harper — and went further, saying that the team had “created and perpetuated a working environment that was hostile to minorities.”57

In December, the two parties reached a settlement that forestalled a federal lawsuit against the Red Sox. The financial terms were, of course, confidential, and there was no admission of liability on either side, but the agreement was accompanied by public covenants that the Red Sox would undergo semiannual review of their employment practices to ensure nondiscriminatory employment practices.58

Harper also began to work for UPS and in the summer of 1987 worked running a summer baseball program for the City of Boston Parks Department. That November, the Montreal Expos hired him to become the team’s minor-league baserunning instructor.59

A bit of an olive branch was extended when Harper was included in the 1989 Old-Timer’s Game at Fenway Park in May 1989.

He was promoted to Montreal’s major-league staff in late 1989 and served as Montreal’s first-base coach from 1990 through 1992 and their hitting coach from 1993 through 1999.

In January 2000, Harper was hired to coach for the Red Sox under manager Jimy Williams. He coached for the next three seasons, through 2002. “This is like night and day,” he said in February 2000. “This is a different atmosphere altogether. It’s refreshing. It’s not the e as it was. It’s a lot better, and the Red Sox as an organization have done it quietly.”

As Grady Little began his second year as Red Sox manager, he moved to bring in his own coaches, and the Red Sox fired both hitting instructor Dwight Evans and Harper in October 2002. Harper said, “I’m not in any way upset. I had three wonderful years here.”60

A significant change had occurred under new ownership, Harper felt. “When John Henry, Tom Werner, Larry Lucchino bought the team, yes, there was a definite change,” he said. “There are changes that maybe you can’t see, but I see. There’s a different attitude. There’s a feeling of genuineness. … As a black person, yes, I do feel a difference. I can’t put a finger on it. But it’s not because they hired this guy or that guy. No, it’s not that. It’s not numbers. It’s how well you’re treated.”61

After being relieved of his position as coach, Harper was named a special assignment instructor with the Red Sox, appearing in the 2003 Media Guide as such, along with Dwight Evans, Johnny Pesky, and Charlie Wagner. He thus earned his first world-championship ring in 2004, and has since earned two more, in 2007 and 2013, though his title became player development consultant along the way.

Tommy and his wife, Bonnie, have lived in the Greater Boston area for many years.

In 2009, Harper worked closely with Jacoby Ellsbury on basestealing and saw Ellsbury surpass his franchise mark for stolen bases. Just a couple of days before Ellsbury broke the record, Harper approached him in the clubhouse, and playfully said, ” ‘I’m going to kick you in the knee,’ … faking an assault on Ellsbury’s leg. Ellsbury laughed as he feigned collapsing on the bench. Both knew how Harper really felt. They faced the field, and Harper placed his hand on Ellsbury’s shoulder. ‘I’m here,’ Harper told him. ‘Do it tonight.’”62

In 2010, Tommy Harper was named to the Red Sox Hall of Fame. As 2017 closed, he remained a Player Development Consultant for the team.

Last revised: December 1, 2018

This biography appeared in “Time for Expansion Baseball” (SABR, 2018), edited by Maxwell Kates and Bill Nowlin.

Notes

1 A considerable number of other players have since joined the 30-30 Club, including Bobby Bonds’ son Barry Bonds.

2 Bill Deane, “Here Are Top Candidates to Join Elite ’30–30′ Club,” Baseball Digest, May 1987.

3 Rich Marazzi, “Tommy Harper,” Sports Collectors Digest, February 27, 1998: 80.

4 Earl Lawson, “Harper Is 3-Sport Athlete,” Cincinnati Post and Times Star, March 2, 1962.

5 As sportswriter Billy Reed put it, he got his first major-league hit “even though he didn’t mean to. Harper started to swing at [an Art] Mahaffey pitch, but tried to hold back. The ball hit his bat and looped into right field for a single.” See Billy Reed, “Reds, Phils Switch Roles for Opener,” Lexington (Kentucky) Leader, April 10, 1962: 8.

6 “Reds Ship Harper to S.D.,” San Diego Union, April 16, 1962: 25. Harper agreed: “The pressure got me,” he said a year later. Earl Lawson, “Harper’s Record Rips No-Hit, No-Field Tag Off Reds’ New Rookie,” The Sporting News, March 9, 1963.

7 Jack Murphy, “Speaking of Gilman, Harper, Littler and Assorted Topics,” San Diego Union, July 29, 1962: 147.

8 Steven S. Scheuer, “Beauties Parade Tonight,” San Diego Union, July 14, 1962: 27.

9 Coincidentally, all three players completed high school near one another. Both Pinson and Robinson were graduates of Oakland’s McClymonds High.

10 Associated Press, “Hutch: Reds Looking for Men to Push Regulars Out of Job,” Lexington Leader, February 21, 1963: 18.

11 “Weddings,” Jet, April 11, 1963: 39.

12 “Jesse Gonder, Tommy Harper on All-Star Rookie Team,” Atlanta Daily World, September 25, 1963: 7.

13 Marazzi.

14 Ibid.

15 Harper told Rich Marazzi that Bristol was his favorite manager.

16 Associated Press, “Locked Up Red Pays Debt,” Charleston (South Carolina) News and Courier, January 20, 1967: 17.

17 Earl Lawson, “Harper Power Secret Weapon; ‘Call Me Bunter,’ He Requests,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1965.

18 Russell Schneider, “More Tribe Deals Due,” Plain Dealer (Cleveland), November 22, 1967: 25.

19 “Tommy Harper Restless, Hits Dark’s Platooning,” Chicago Daily Defender, May 18, 1968: 16.

20 Hy Zimmerman, “Base-Burglar Harper Says His Bat Calls Tune,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1969: 5.

21 Georg N. Myers, “The Sporting Thing,” Seattle Daily Times, April 13, 1969: 29.

22 Lee D. Jenkins, “Schultz Lauds 2,” Chicago Daily Defender, March 1, 1969: 16.

23 Marazzi. Ed Rumill picked up on this early in the season, quoting Schultz in May as saying, “I’ve turned him loose. … It gave him confidence.” Ed Rumill, “‘Go’ Sign Sparks Harper,” Christian Science Monitor, May 24, 1969: 11.

24 See Rumill.

25 August 22 was Tommy Harper Night at Sick’s Stadium and every fan attending the game was given a color photograph of “Tailwind Tommy.” See advertisement on page 75 of the August 21 Seattle Daily Times. Harper had two singles and a walk, but the Pilots lost, 9-8.

26 Ibid.

27 “Brewer’s (sic) Tommy Harper Having Great Year,” Milwaukee Star, August 8, 1970: 17. With the Reds, he said, the winning and losing tended to rest on the shoulders of Pinson and Robinson.

28 Tim Horgan, “Which Was Worse — The Ball Game or Sox Trade? Weaver Likes Both,” Boston Herald, October 12, 1971: 33.

29 Clif Keane, “Sox Brass Sing No Sad So-longs,” Boston Globe, October 12, 1971: 25.

30 Tim Horgan, “Harper Answers All Questions,” Boston Herald, October 20, 1971: 44. The headline was meant to be ironic; to every question that Harper was asked, he replied, “No comment.”

31 Larry Claflin, “Moret Top Disappointment on Sox,” Boston Record American, March 25, 1972: 33.

32 Larry Whiteside, “Milwaukee Baseball Writer: ‘Red Sox Getting 3 Real Pros,’” Boston Globe, October 12, 1971: 25.

33 Fred Ciampa, “First Things First! Yaz Belongs in LF,” Boston Record American, January 12, 1972: 54.

34 “A Message from the Publisher,” Boston Herald, June 24, 1972: 2.

35 Tim Horgan, “DH Rule Splits Sox Camp,” Boston Herald, March 4, 1973: 38.

36 Bill Liston, “Harper Using Speed in New Fashion,” Boston Herald, March 5, 1973: 24. Harper said that stealing bases works best when the baserunner sees the opportunity, not when he gets the nod from the dugout. Phil Elderkin, “Red Sox Harper — He Runs to Steal,” Christian Science Monitor, April 10, 1974: F3.

37 Tim Horgan, “Gas Shortage to Curb Red Sox Crowds,” Boston Herald, March 2, 1974: 17.

38 Boston Globe, February 16, 1974: 21.

39 Larry Claflin, “The Pressure’s on Johnson,” Boston Herald, March 3, 1975: 26.

40 Ross Newhan, “Harper’s Out to Prove the Angels Got a Steal,” Los Angeles Times, March 30, 1975: C9.

41 Dick Miller, “Angels Strumming Their Harps Over Harper,” The Sporting News, March 29, 1975: 33.

42 “Rivers Credits His Thievery to Harper,” Boston Globe, August 24, 1975: 80.

43 Owen Canfield, “Harper Accepts New Role,” Hartford Courant, May 21, 1978: 4C.

44 Bill Liston, “Dodgers Pondering Tigers’ John Hiller,” Boston Herald, November 12, 1977: 8.

45 United Press International, “New Role for Harper,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Union, March 1, 1978: 50.

46 Bob Hohler, “Memories Still Haunt Harper,” Boston Globe, September 21, 2014: C1.

47 “Harper Heads Hiring Plan,” Boston Herald, May 18, 1978: 48.

48 Larry Whiteside, “Harper Has a Mission for Sox, Blacks,” Boston Globe, July 29, 1979: 77.

49 Larry Whiteside, “Jim Rice’s Dilemma,” Boston Globe, March 9, 1980: 66.

50 Bob Hohler.

51 Peter Gammons, “Ready or Not? Stapleton’s Pact Poses Problems,” Boston Globe, February 25, 1985: 32.

52 Michael Madden, “Tacit Complicity?” Boston Globe, March 15, 1985: 23. Harper later said he had tried to work things out quietly with the Red Sox the year before the story surfaced in the press. See Dan Shaughnessy, “Harper Sign of Red Sox’ Redemption,” Boston Globe, February 28, 2000: D1.

53 Ibid. Madden’s story goes into considerable detail on the history. Harper also noted that Frank Robinson had quietly resolved a racial discrimination issue during the season the two were teammates in Cincinnati. See Gordon Edes, “Harper Finally at Home,” Boston Globe, February 1, 2006: D2.

54 Michael Madden, “Harper’s Firing” Sox Dishonor,” Boston Globe, December 28, 1985: 29. Peter Gammons followed with a January 5, 1986, article entitled, “It’s Time for Sox to Turn a New Leaf” in which he stepped back and looked at the bigger picture on the Red Sox. See also David Margolick, “Boston Case Revives Past and Passions,” New York Times, March 23,1986: S1.

55 Michael Madden, “Harper: Sox Are Racist,” Boston Globe, January 31, 1986: 39.

56 Will McDonough, “Sox Racist? Says Who?” Boston Globe, April 17, 1986: 51.

57 Michael Madden, “Harper’s Charges Against Sox Upheld,” Boston Globe, July 2, 1986: 67. Harper said the Red Sox had twice tried to reach a settlement with him, but that he had rejected their offers out of principle.

58 Larry Whiteside, “Sox, Harper Settle,” Boston Globe, December 6, 1986: 21.

59 Dan Shaughnessy, “Harper Sign of Red Sox’ Redemption.”

60 Bob Hohler, “Evans, Harper Fired; Sox Moves Signal Little Is Secure” Boston Globe, October 5, 2002: G1.

61 Gordon Edes, “Harper Finally at Home.”

62 Adam Kilgore, “Harper Waits to Pass Baton,” Boston Globe, August 24, 2009: C7.

Full Name

Tommy Harper

Born

October 14, 1940 at Oak Grove, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.