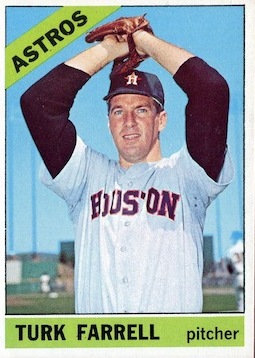

Turk Farrell

A late-inning home run by Willie Mays was the decisive blow in San Francisco’s dramatic 2-1 victory on the last day of the 1962 regular season, clinching a playoff berth for the Giants against their downstate rival Los Angeles Dodgers. Meanwhile, Dick “Turk” Farrell, the right-handed hurler for the Houston Colt .45s who surrendered the blow, absorbed his 20th loss in the team’s inaugural campaign, thereby etching his name on the short list of eight pitchers selected to the All Star squad while going on to 20 losses in the same season.1

A late-inning home run by Willie Mays was the decisive blow in San Francisco’s dramatic 2-1 victory on the last day of the 1962 regular season, clinching a playoff berth for the Giants against their downstate rival Los Angeles Dodgers. Meanwhile, Dick “Turk” Farrell, the right-handed hurler for the Houston Colt .45s who surrendered the blow, absorbed his 20th loss in the team’s inaugural campaign, thereby etching his name on the short list of eight pitchers selected to the All Star squad while going on to 20 losses in the same season.1

Farrell was the master of a “blazing fastball [that] frightened batters … [wherein] a foul ball … was considered a big achievement,”2 and no less a personage than the great Ted Williams would lament Boston’s decision not to sign the youngster when he participated in a Red Sox tryout at Fenway Park in the early 1950s.3 A Massachusetts native who played prep ball against fellow major-leaguer hurlers Jack Sanford and Bill Monbouquette, Farrell was instead signed by the Philadelphia Phillies in 1953 and reached the major leagues three years later, making a big splash out of the bullpen while invoking the former success of Jim Konstanty of Whiz Kids fame.

Richard Joseph Farrell, born in Boston on April 8, 1934, was the older of two children of Tom and Mary Farrell (a sister, Donna, arrived 11 years later). His father, a grave keeper at Holyhood Cemetery in nearby Brookline, was an accomplished amateur athlete of sizable proportions that earned him the nickname Big Turk. (At a robust 6-feet-4 and 215 pounds, Dick could hardly be called Little Turk, and became simply Turk.) Dick’s mother, Mary (Gavin) Farrell, had immigrated in her teens to the Boston area from County Mayo in Ireland, and often worked as a domestic housekeeper.

Dick faced challenges almost immediately when he was stricken with polio before his second birthday. He wore a brace on his left leg until he was 6, and he underwent hospital treatment on a regular basis until he was 18. The disease caused his left foot to be 1½ inches shorter than his right, and the left calf to be almost 2 inches smaller in circumference. Family lore tells of Dick’s mother sitting her son down and pulling on his shorter leg, causing such pain that it brought tears streaming down the youngster’s cheeks. Whether because of this homemade remedy, the continual hospital treatments, or both, Farrell overcame the disease – albeit with a slight, permanent limp his entire life – to become one of the greatest athletes ever produced by St. Mary’s High School in Brookline, Massachusetts.4

A standout in basketball and football as well as baseball, Farrell passed on a number of athletic scholarships to sign with the Phillies right after high-school graduation. He became the only St. Mary’s graduate to make it to the major leagues – Joseph Sullivan played professional ball in the 1930s, but never advanced past the Class D minors. Under the six-year tutelage of Bob Whelan, who was his coach in middle school and high school, and went on to become the director of scouting for the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 1960s, Farrell won nine state playoff games without defeat, and a nice 45-5 record overall, from his sophomore year on.

At 19 years old, Farrell reported less than 200 miles from home to the Schenectady (New York) Blue Jays in the Class A Eastern League. A nice showing in a half-season of work – 7-3, 3.39 earned-run average in 16 appearances – was rewarded with an invitation to Clearwater, Florida, the following spring to show off his wares before the parent club in spring training. The Phillies were a mere four years removed from a World Series appearance gained largely on the strength of a mound corps anchored by future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts, and Farrell’s chances of breaking into this rotation in 1954 were slim – but the fact that he was presented this early opportunity spoke volumes to the high expectations the Phillies had in the young righty.

Reassigned to the Blue Jays, Farrell posted a deceptive 11-15 mark for a last-place club with league lows in runs scored and team batting average (a paltry .229). A 3.21 ERA in 40 appearances – 27 as a starter – was far more indicative of the emerging talent, resulting in a two-level promotion to the Triple-A affiliate Syracuse Chiefs of the International League in 1955. Once again Farrell was hurling for a second-division club, and his 12 victories – including a two-hit shutout against the Richmond Virginians on May 26 – placed him among the league leaders in wins. Farrell also displayed his talent with the bat when, on July 7, the righty hitter struck the season’s longest round-tripper – estimated at 475 feet – at Syracuse’s MacArthur Stadium that helped secure a 3-1 victory over the Toronto Maple Leafs.

At season’s end the Phillies sent the 21-year-old righty to the Venezuelan Association. A sterling start to the winter campaign resulted in four straight victories, including a 2-0 shutout. Farrell’s initial success continued in the playoffs when he tossed a one-hit masterpiece against Puerto Rico in the Caribbean Series. Farrell appeared poised to make the jump to the parent team the following spring.

Although the Phillies were now relegated to a .500 club, they still maintained a mound presence that placed the 1955 squad among the NL leaders, and Farrell continued to struggle to break into the rotation. He was assigned to the Miami Marlins, a new entry in the International League owned by Bill Veeck that contained players – most notably Satchel Paige – aligned more with Veeck than the Phillies. Tabbed as the Opening Day starter for the new franchise, Farrell suffered a broken ankle five days before the assignment that set him back about two months. Once unleashed, Dick posted a 12-6, 2.50 mark that included a one-hitter he lost 2-0 because of an uncharacteristic 10 walks issued. Still, Farrell’s overall numbers, combined with the efforts of Don Cardwell, Jim Owens, and the other young Marlin hurlers, caused Phillies farm director Gene Martin to chirp that “at Miami we had the best young pitching staff ever assembled in the minors.”5

Seventeen days after the near no-hitter, Farrell made his major-league debut on September 21. Coming five days after the Phillies debut of his high-school competitor Jack Sanford (from Wellesley, Massachusetts), Dick took the mound at the Polo Grounds on September 21, 1956, against the New York Giants. Four innings of two-hit ball offered encouragement that was quickly dashed in the fifth when a base on balls followed by a hit batsman opened the floodgates to a seven-run outburst that handed Farrell his first-major league defeat.

In 1955 young righty Jack Meyer had taken the reins from Jim Konstanty as the Phillies full-time closer, but Meyer did not fare nearly as well in 1956. As the Phillies reviewed their corps of young hurlers for the 1957 season, they tapped Farrell to take on the closer role. Although this may have come as quite a surprise to Dick – he’d started in over 75 percent of his 112 appearances in the minors – the move corresponded with an existing trend in the major leagues at the time. “Before World War II,” noted The Sporting News, “a big league manager usually picked his clutch relief pitcher from among the curve-balling veterans of his staff, but more and more fastball pitchers, many of whom have never had a full shot at a big- league starting job, are often the top emergency hurlers now. Joe Page, Joe Black, Ray Narleski, Don Mossi and the Phils’ Meyer were of that type and in Farrell the Phils have apparently come up with another from the same mold.”6

Farrell’s impact was both immediate and extremely positive as his ten wins and ten saves combined (the saves are retrospective; they were not a statistic in those days) accounted for more than a quarter of the Phillies’ 77 victories in 1957. Farrell made his mark in many ways, evidenced by the two saves secured in both games of a July 7 twin bill against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field. His first major-league home run was a gargantuan blow against Don Newcombe on June 2 at Connie Mack Stadium – landing on the left-field roof and bouncing over into the street – that contributed to his third victory of the season. By the end of the campaign, Farrell was nearly unhittable, going 6-0 with one save in his last 14 appearances (spanning 21 innings) while yielding just 12 hits and no earned runs. His 52 appearances were the most by a Phillies hurler since Konstanty in 1951. On the merits of such fine relief work, Farrell would not see a starting assignment for five years.

Even with such superb numbers, Farrell was not even the best rookie pitcher on the staff; Jack Sanford garnered NL Rookie of the Year honors with 19 wins as a starter. The Baseball Writers’ Association of America selected Farrell to their Rookie All-Star team along with Sanford and two other Phillies, a remarkable display of youth that would soon pave the way for a complete rebuild for the Philadelphia squad. Management made clear that with few exceptions – Farrell being prominent among these – the team was willing to entertain trade offers for many of their veteran players, and in this youthful pursuit, the Phillies would soon begin a stretch of last-place finishes for four consecutive seasons.

Diverse is probably the best word to use in describing the 1958 season for Farrell. He picked up right where the preceding season left off, and his early-season success resulted in his first selection to the NL’s All Star squad. The scoreless string that Farrell had fashioned at the end of the 1957 campaign was continued into 1958, ending on May 6 after 35? innings. He was runner-up to Frank Thomas for NL Player of June when he yielded only two earned runs in 24-plus innings of work (11 appearances) while posting four wins, two saves, and 28 strikeouts for the month. Farrell earned accolades from Dodgers manager Walt Alston, who compared his blazing fastball to that of his own ace Don Drysdale,7 and he was selected to the All Star team on the strength of a minuscule 1.07 ERA after 25 appearances (nearly 59 innings of work).

The accolades continued after Farrell’s dominant two-inning stint in the 1958 All-Star Game. He yielded one walk against four strikeouts, including a superb three-pitch mastery over Ted Williams, that led Giants manager Bill Rigney to say, “[I]f we had [Farrell] in the bullpen, we’d win it [all].”8

But an abrupt detour was in Farrell’s immediate future. Eight days after his All Star performance, he was bombarded by the Chicago Cubs in his first-ever appearance in which he did not garner at least one out. Over the next two months (22 appearances), Farrell had difficulty getting anyone out, as an unsightly 9.82 ERA in 25? innings demonstrated. Two theories developed as to this sudden reversal: a hay fever allergy, and overwork.

The allergy was not diagnosed until that winter, but it unfolded into an asthmatic state that weakened Farrell throughout the remainder of the season. “I thought I had a sinus condition,” he said in March 1959. “Whatever it was, it made me feel miserable and I didn’t sleep very much.”9 When the condition was finally diagnosed accordingly, both the Phillies and Farrell hoped that proper treatment would result in a return to the youngster’s earlier success.

Still, another scenario more than likely contributed to Farrell’s second-half woes in 1958. He had appeared in more than one-third of the Phillies’ games (25 of 72) prior to the All Star break. The ineptitude of the bullpen – a ghastly 5.32 ERA from relievers other than Farrell – meant almost continuous appearances by Farrell, and this sustained use came at a costly price. The resulting wear not only affected Farrell’s pitching in the second half of 1958, but contributed to a general ineffectiveness in 1959 as well.

There were some rather embarrassing outings for Farrell in 1959. On June 26 he entered a game with the bases loaded and the Phillies losing 3-0 to the Giants, and on his first pitch gave up a grand slam to Jackie Brandt. Two weeks later, after entering a close contest against St. Louis, he gave up home runs on his first two pitches. Other such outings contributed to a demotion to Buffalo for a month and a record of 1-6, 4.74 for the season. Having once been the darling of the bullpen, Farrell was soon targeted as one of the culprits in the team’s 90-loss campaign.

A syndicated sports columnist in New York wrote that the Phillies were a team of playboys, “a club going no place … and caring less.”10 Farrell received particular attention as the ringleader, along with fellow pitchers Jim Owens and Jack Meyer, of the Dalton Gang, the title ascribed to the perceived corps of hard-partying young men. Admittedly, Farrell could be described in many ways – fierce competitor; prankster; beloved teammate – but Boy Scout would never be one such attribute.

At the age of 25, Farrell had already developed quite a reputation. When he was with Syracuse in 1955, he and a teammate were charged with assault after a restaurant altercation with a sportswriter. A jury tossed out thecharges. In April 1959 he was fined $250 by Phillies manager Eddie Sawyer for “conduct unbecoming a major league ball player”11 after smashing a mirror with his fist in a Milwaukee bar. But there were other dimensions to Farrell as well, including a witty, dry sense of humor evidenced by:

- Farrell had occasion to visit the Dalton Gang Hideout and Museum in Meade, Kansas, which prompted the following message to a sportswriter friend: “Stopped off at the old hideout … [b]rought back memories. Takes a while to raise a new gang, but will start soon.”12

- While representing a music firm selling record players to bars and lounges one offseason, Farrell quipped that he “had a ready-made advantage in this business … [knowing] most of the bars and lounges.”13

- Before a game against Milwaukee, Farrell took some of the night’s game balls and wrote a number of unprintable notes directed toward the opposing pitcher, Lew Burdette. When the Braves’ hurler discovered these messages, he was often seen yelling into the Houston dugout: “The same to you, Farrell!”14

There also existed a more imposing presence to the burly righty. In a match against the Giants in 1962, Farrell plunked Willie Mays, prompting a considerable amount of vitriol from the Giants dugout. Farrell eventually turned to the Giants’ bench and, at the top of his lungs, said: “I’ll take any one of you guys – or any two – right now!”15 He had no takers.

Perhaps it was a combination of the New York columnist’s perception of the players’ “caring less,” plus the reported need for a “reliable relief pitcher”16 for the Phillies, that caused Farrell to train more diligently than ever before on the eve of spring training in 1960. The results were immediate in the Grapefruit campaign – prompting trade inquiries from his native Boston – and translated into a successful comeback season for the flamethrower. Farrell’s 10 wins and 11 saves accounted for nearly 36 percent of the Phillies’ 59 victories, while a 2.70 ERA was the team’s best for any pitcher with over 100 innings. Farrell appeared in a career-high 59 games. Undoubtedly with the thought of selling high, the Phillies were soon entertaining a large number of trade offers for him during the offseason.

For a team coming off a 95-loss season, it could rightly be assumed that the Phillies had many needs to fill to become competitive again. They appeared to have entered the trade market hoping to fill most, if not all, of those needs on the back of their righty reliever. Farrell’s name was linked to a variety of trade possibilities that included such notables as Frank Robinson, Joe Adcock, Yogi Berra, and Elston Howard, and Cleveland Indians general manager Frank Lane may have accurately assessed that the Phillies were “asking too much” for the relief hurler.17 Unable to reach a satisfactory exchange, the Phillies opened the 1961 campaign with Farrell still on the squad, but his presence would not last long.

The Los Angeles Dodgers were one year removed from a world championship, and their interest in Farrell was twofold: They had lost closer Ed Roebuck to a shoulder injury, and Farrell was perceived to be more than a suitable replacement; and they wanted to make sure Farrell was not traded to their anticipated close competitor, the Milwaukee Braves. Meanwhile, Farrell’s stock dropped considerably (6.52 ERA) in five early-season appearances, and the Dodgers were able to acquire him for two journeymen players.

Unfortunately for Farrell, the poor early start in Philadelphia developed into a dismal season-long output. A sudden penchant for surrendering walks and home runs resulted in a 5.06 ERA in 50 appearances with the Dodgers. The team lost the pennant by four games to the Cincinnati Reds, and Farrell got the lion’s share of blame. With Roebuck expected to return in 1962, the Dodgers left Farrell unprotected in the pending expansion draft, and the Houston Colt .45s general manager, Paul Richards, who had coveted Farrell from his early days, drafted the pitcher. Richards and manager Harry Craft immediately envisioned a new role for Farrell, as a starter. Houston acquired relief specialist Don McMahon from the Braves, and freed up Farrell to remain part of the starting rotation. Over the next five seasons he was used primarily in this role.

Like most expansion teams, Houston struggled during its inaugural season. Over a five-week stretch beginning June 23, the club posted a 5-29 record. Farrell was not immune to this tailspin; as a 5-14 record to close out the season contributed largely to his 20-loss campaign. Still, of the nearly 500 pitchers who have lost 20 games in a season, Farrell’s 3.02 ERA remains the best since Hall of Famer Jessie Haines posted a 2.68 ERA with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1920. Farrell was on the losing end of some heartbreaking defeats, evidenced by a 2.78 ERA in 11 starts that resulted in no wins against 10 losses. (He lost two consecutive three-hit outings when the team was shut out both times.) In Houston’s first three seasons, its offense produced the fewest runs in the National League each year. Accumulated losses notwithstanding, Farrell’s efforts were recognized when he was named to the National League All-Star team as Houston’s lone representative in 1962, though he did not play in the game. At year’s end, manager Harry Craft said of Farrell: “(H)e’s one of the league’s very best pitchers, and one who can continue to rank at the top for several more seasons.”18

In 1963 Houston matched its inaugural output of 96 losses while Farrell carved an identical 3.02 ERA. Though he missed a handful of appearances after hurting his back in early June, Farrell led the club with 14 victories and 12 complete games. He was one of 14 major-league pitchers whose victories exceeded 20 percent of their team’s wins for the season (one of whom was his former high-school opponent, Bill Monbouquette).

In hopes of improving upon the two straight 96-loss campaigns, Houston made wholesale changes; still, they lost 96 games again in 1964 (and 97 in 1965). Entering the 1964 campaign, Farrell was one of only five players remaining from the original expansion-draft team. One addition to the team, a player quite familiar to Farrell, was Jim Owens – thereby uniting two-thirds of the Dalton Gang from the Philadelphia days.

Meanwhile, Farrell had settled down considerably – in fact, he was often adamant about the alleged exploits of the past, claiming that they were too frequently blown out of proportion. Turk, his wife, Grace, and their three children moved from Boston to Houston after the 1963 season. Dick and Grace’s marriage was initially of the storybook variety – high-school sweethearts, with the acclaimed school jock tying the knot with the majorette and lead cheerleader. (The marriage dissolved in less than 20 years, and Grace died in Houston in 1995 after a series of health issues.)

Farrell spent the offseason between 1963 and 1964 pitching season-ticket plans for the Colt .45s for the coming campaign. Using skills honed by working in public relations for a construction company in Philadelphia, Farrell helped establish a then-record number of season-ticket packages for the Houston club. In prior years (1958-60), Farrell also garnered offseason paychecks by participating in major leaguers’ barnstorming tours. He also worked at times alongside his father at the Brookline cemetery.

It is not hard to conceive that based on the manner in which Farrell began the 1964 season he was determined to single-handedly satisfy each of the season-ticket holders to whom he had sold packages. Slightly more than one-third of the way into the campaign, Farrell appeared well on his way to 20 wins – 10-1, 2.41 ERA. The first pitcher to reach the ten-win threshold, he was an easy choice for the All Star game at Shea Stadium in New York, where he hurled two innings in relief. Farrell’s Houston teammates were surprisingly averaging five runs per game in the righty’s rapid ten-win pace. But the Houston offense soon reverted to its more familiar clip, evidenced by eight starts – all losses – in which Farrell was supported by a total of 12 runs. He finished with a mark of 11-10, 3.27.

Domed play arrived in the major leagues with the opening of the Astrodome in Houston in 1965. Mickey Mantle hit the first home run in the Astrodome in an exhibition game. The round-tripper was surrendered by Farrell. The outstanding memory of Farrell this season was a far more painful one – an assist captured when a line drive off the bat of Hank Aaron struck him in the back of the head and was caught by second baseman Joe Morgan in short center field.

Though Farrell again posted respectable numbers for the continual second-division club – while being selected to the All Star squad for the fourth and last time – the team began to actively solicit trade offers for Turk. Published reports indicated that management was “anxious about the big fire-balling Irishman,”19 a reflection perhaps that Farrell was losing some velocity from his fastball, and his name was soon linked to a variety of trade possibilities, one of Farrell and third baseman Bob Aspromonte for Cincinnati slugger Frank Robinson. (Robinson was eventually traded to Baltimore for pitcher Milt Pappas.)

As Houston continued to both pitch and receive trade offers, the anxiety about their “fire-balling Irishman” seemed to have come to fruition during the 1966 season. Although Farrell had a large repertoire of pitches in his arsenal – his name was prominently mentioned alongside Don Drysdale and others when baseball sought to crack down on the old-fashioned spitball before the 1968 season – his primary out-pitch had always been a blazing fastball. At 32 years of age, it appeared that his arm could no longer endure the strain when he acknowledged that “I know I’m slowing down a little. … I can’t just challenge the good hitters with the fast ball.”20

This acknowledgment soon became evident on the field as Farrell’s propensity for surrendering the home-run ball contributed to an ERA over five through much of the season, and eventually relegated Farrell to the bullpen. He actually thrived in this once-familiar role – an indication that his fastball was still effective in much shorter stints. Excluding one very bad outing against the Pirates in mid-September, Farrell fashioned a very nice 0.93 ERA in over 19 innings of relief to close out the campaign. Barring one ineffective spot start for the Phillies in 1967, Farrell worked exclusively from the pen for the remainder of his major-league career.

Entering the 1967 season, the Phillies were no longer the NL’s doormat. Under the direction of manager Gene Mauch, they had posted a .546 winning percentage over the preceding four seasons that included at least one unsuccessful championship endeavor. In an attempt to bolster the bullpen for another pennant pursuit, the Phillies secured Turk Farrell from the Houston Astros on May 8, 1967, for a mere $35,000 – a far cry from the likes of a potential Frank Robinson acquisition 17 months earlier. As it turned out, Farrell and 36-year-old Dick Hall (acquired five months earlier) became the mainstays of the team’s relief efforts. Although the club plummeted to a distant fifth-place finish because of an offensive collapse, Farrell posted one of the finest seasons of his career: 9-6, 2.05 with a team-leading 12 saves in 50 appearances (92 innings) for the Phillies. He displayed his once-unhittable self again when he did not yield a single run during a six-week period beginning July 17 – a stretch spanning 32 innings in 20 appearances. His ten wins in relief (one of them with Houston) were the most by an NL reliever, and even though he was closing in on his 34th birthday, the Phillies were looking to him for continued long-term success. “I believe Farrell is a freak,” Mauch said. “By this I mean I believe this man can go on maybe for four or five more years.”21

More than two months into the 1968 campaign, Mauch’s words regarding Farrell appeared to ring true as the righty accumulated eight saves and three wins (accompanied by a 1.50 ERA) in 36 innings of work. The remainder of the season did not go as swimmingly: a 5.01 ERA in nearly 47 innings of work that produced a 1-4 mark. On the strength of his early work, Farrell still paced the Phillies with 12 saves, but the second-half swoon carried over into the following campaign, resulting in his last season in a major-league uniform. The once-unhittable righty was no longer so, surrendering 92 hits and 33 runs in a little more than 74 innings, and he was released after the season.

Over the next two years Farrell bounced around between unsuccessful tryouts with the Yankees and the Montreal Expos to minor-league stints in the Braves and Cardinals organizations, culminating in a brief spell in the Mexican League in 1971 (over the course of these campaigns, he served under a cast of All Star managers that included Mickey Vernon, Warren Spahn, and Minnie Minoso). Farrell finally set aside his spikes and glove and went to work in sales before eventually moving over into the oil and gas industry – hired by the engineering and construction firm Brown and Root as a safety supervisor working on foreign offshore rigs. It was while employed in this capacity, drilling wells in the North Sea, that tragedy struck. Less than 600 miles from his mother’s birthplace in County Mayo, Ireland, Farrell, just 43 years old, was killed in an automobile accident in Great Yarmouth, England, on June 10, 1977.

Six months later, in December, Dick’s 20-year-old son, Richie Jr., died of injuries suffered in a motorcycle accident in Houston. At the age of 3, the youngster had captured the hearts of players and fans by dancing the twist at home plate during a father-and-son celebration in Philadelphia. He was buried alongside his father in Forest Park Westheimer Cemetery in Houston. He was joined by his mother, Grace, 18 years later. (Farrell’s daughters had arranged for her to be buried there – near her ex-husband – so that she could be next to her son.) As of January 2013, Turk was survived by his daughters, Kathy and Kim; four grandchildren; and three great-grandchildren. His second wife, Frances, also survived.

A one-time prankster described as “fun loving,” Dick Farrell was also an accomplished athlete who overcame what could easily have been a lifelong disease, but was taken from us early. He was truly a character in every sense of the word. He was, and remains, sorely missed.

In September 2020, an article in The Athletic revealed publicly that Farrell was the biological father of another accomplished big-league pitcher: Richard Dotson.22

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Kathy Lykke, daughter of Turk Farrell, for her time and assistance in ensuring the accuracy of the family history.

Sources

Notes

1 Besides Farrell, those pitchers are Hugh Mulcahy, 1940 Philadelphia Phillies; Eddie Smith, 1942 Chicago White Sox; Ken Raffensberger, 1944 Phillies; Bob Rush, 1950 Chicago Cubs; Sam Jones, 1955 Cubs; Mel Stottlemyre, 1966 New York Yankees; and Steve Rogers, 1974 Montreal Expos.

2 “Young Ideas,” The Sporting News, July 2, 1977, 15.

3 “Background Held Down Hits,” The Sporting News, July 16, 1958, 9.

4 “Farrell Big Flash as Philly Fireman,” The Sporting News, June 5, 1957, 15.

5 “Phils Eye Notre Dame Boy,” The Sporting News, October 24, 1956, 2.

6 “Farrell Earns Fireman’s Hat on Smoke Ball,” The Sporting News, September 11, 1957, 20.

7 “Surgery Scar Bars Bermuda Shorts for Duke,” The Sporting News, March 19, 1958, 16.

8 “Bouchee’s Return Helps Phillies,” The Sporting News, July 16, 1958, 12.

9 “Phillies Figuring on Big Lift From Fire Ladder Pair,” The Sporting News, March 11, 1959, 21.

10 “Ed Sawyer Scoffs at Charge Phillies Are Playboy Team,” The Sporting News, April 29, 1959, 7. The columnist was not identified in The Sporting News’ article.

11 “ ‘Conduct Unbecoming Player’ Costs Farrell a $250 Plaster,” The Sporting News, April 22, 1959, 9.

12 “A Frolic With Farrell,” The Sporting News, June 8, 1963, 28.

13 “Credit to Astroturf,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1968, 42.

14 “Diamond Facts and Facets,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1962, 30.

15 “Diamond Facts and Facets,” The Sporting News, September 1, 1962, 14.

16 “To Market, To Market for 16 Clubs,” The Sporting News, September 30, 1959, 16.

17 “Phils Placing Top Price on Twirling Trio,” The Sporting News, December 14, 1960, 25.

18 “Farrell Rated Double-Barreled Dilly by .45s,” The Sporting News, November 3, 1962, 7.

19 “Notty’s a Problem – Just Ask Swingers He’s Been Fooling,” The Sporting News, April 10, 1965, 32.

20 “Farrell Ready for Double Duty As Astros’ Starter and Reliever,” The Sporting News, February 5, 1966, 25.

21 “Phil Gamble on Hall And Farrell Paid Off In Bullpen Bonanza,” The Sporting News, November 18, 1967, 43.

22 Jayson Stark, “‘There might be a family secret’: Richard Dotson’s real-life fable,” The Athletic, September 11, 2020, https://theathletic.com/2056094/2020/09/11/there-might-be-a-family-secret-richard-dotsons-real-life-fable/

Full Name

Richard Joseph Farrell

Born

April 8, 1934 at Boston, MA (USA)

Died

June 10, 1977 at Great Yarmouth, Norfolk (United Kingdom)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.