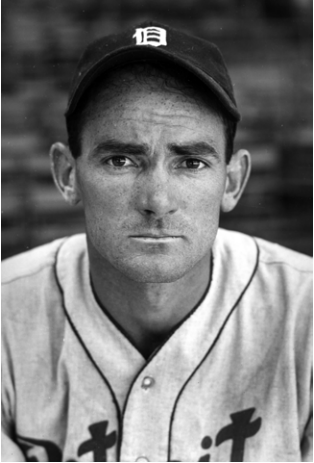

Vern Kennedy

In the spring of 1992, at the age of 84, Vernon Kennedy was still competing athletically.

In the spring of 1992, at the age of 84, Vernon Kennedy was still competing athletically.

At the Missouri Senior Olympics, Kennedy took part in the discus, long jump and shot put. He won a gold medal in the discus, captured a bronze in the long jump, and finished fourth in the shot put.

Kennedy’s success at that track and field competition shouldn’t have come as a surprise. As a 20-year-old college student, he won the decathlon at the prestigious Penn Relays.

Kennedy, who was born Lloyd Vernon Kennedy on March 20, 1907, in Kansas City, Missouri, was a gifted all-around athlete at Central Missouri State Teachers College (Warrensburg, Missouri). In football, he was a three-time all-conference player (as a 6-foot, 175-pound tackle). In track and field, he helped the Mules win four consecutive conference titles. At the 1927 conference meet, he took first place in five events (shot put, javelin, pole vault, discus, and long jump).

On April 29, 1927, in Philadelphia, Kennedy won the grueling 10-event decathlon competition (which took eight hours to complete) with a Penn Relays record of 7,236 points. He took first in three events and tied for first in a fourth en route to his record-setting performance.

Kennedy played 25 seasons of professional baseball, but didn’t play intercollegiate baseball at Central Missouri; the school didn’t field a varsity baseball team until 1956. But Kennedy, who graduated from Central Missouri in 1929 with a bachelor’s degree in education (he majored in history), found time to develop his baseball talents by playing town-team ball.

In the summer of 1930, a scout for the Philadelphia Athletics saw Kennedy, a right-hander, strike out 16 in a game, and offered him a contract. Kennedy signed and began his professional career with Burlington of the Class-D Mississippi Valley League. Kennedy went 6-5 with a 4.18 ERA in 16 appearances for Burlington.

Burlington sold Kennedy’s contract after the 1930 season and the Pirates brought Kennedy to spring training in 1931 and 1932. Kennedy said that in those two years he was the “forgotten man” – ignored by everyone.1

Kennedy split the 1931 season between Hazleton of the Class-B New York-Pennsylvania League and Wichita of the Class-A Western League. He made 12 appearances for each team – going 2-5 with a 6.38 ERA for Hazleton and 2-3 with a 5.40 ERA for Wichita.

In 1932 Kennedy traveled with the team to Pittsburgh out of spring training, but made no appearances for the Pirates and was released in May.2

Kennedy signed with St. Joseph of the Western League and went 13-13 in 29 appearances. After the season, the club did not file a reserve list and Kennedy became a free agent. He signed with Oklahoma City of the Class-A Texas League. In his first seven games, Kennedy said, the team scored only three runs, and he lost all seven games.3

Kennedy regrouped to finish with a team-high 15 victories (and 18 losses) and a 3.49 ERA. After the season, the A’s purchased his contract and he went to spring training with the team in 1934.

In the final days of spring training, the A’s elected to keep Alton Benton, who had been a teammate of Kennedy’s in Oklahoma City, over Kennedy for the final pitching spot on the roster. On April 9, the A’s returned Kennedy to Oklahoma City. But by the end of the 1934 season, Kennedy was in the big leagues. He went 17-18 with a 3.15 ERA with Oklahoma City, and his contract was purchased by the Chicago White Sox in September.

On September 18, 1934, at the age of 27, Kennedy made his major-league debut. He started and pitched 7⅓ innings in a 6-0 loss to the Athletics in Chicago. Kennedy singled in his first major-league at-bat. (A decent hitter, he had a .244 batting average in his 12-year major-league career.)

Five days later, on the 23rd, Kennedy made his second start, against the Cleveland Indians in Chicago. He pitched a complete game, allowing seven hits, in a 2-1 loss to the Indians. He also started Chicago’s season finale, on September 30 in Cleveland. He went three innings and got no decision. In the three appearances, Kennedy was 0-2 with a 3.72 ERA.

After their 53-99 record and last-place finish in 1934, the White Sox were looking for pitching help in 1935, and Kennedy made the club out of spring training. He wasn’t used much in the first six weeks of the season, making just two starts (both no-decisions) and three relief appearances. On May 31, Kennedy made his third start and pitched a complete game, allowing just one earned run, in a 6-2 loss to Cleveland in Chicago.

Eight days later, Kennedy earned his first major-league victory by outdueling Elden Auker and the defending American League champion Detroit Tigers, 3-2. He allowed the Tigers just five hits. Kennedy won five of his next seven starts (with one no-decision) to improve to 6-2.

On August 25, Kennedy pitched a complete game in a 6-1 loss (only three earned runs) to the New York Yankees. Two days later, he pitched two innings of relief to save a 4-3 victory over the Yankees in Chicago.

On August 31, Kennedy provided more relief to the overworked White Sox pitching staff (four doubleheaders in the previous six days). He took a 9-7 record into his start against the Cleveland Indians in Chicago and he pitched the first no-hitter in the American League since 1931. Kennedy aided his own cause with a bases-loaded triple in the sixth inning that gave the White Sox a 5-0 lead (the eventual final score).

With one out in the ninth, Cleveland’s leadoff hitter, Milt Galatzer, hit a line drive to left that threatened the no-hit bid but Al Simmons made a diving catch. Kennedy walked the next hitter, Earl Averill – his fourth walk of the game – to bring Joe Vosmik to the plate. Kennedy got Vosmik, a career .307 hitter who batted.348 with 216 hits, 47 doubles, and 20 triples in 1935, to look at a called third strike.

“I didn’t know I was pitching a no-hitter until the start of the ninth inning,” Kennedy said. “Then the boys told me, and I was limp as a rag when I walked off the mound after throwing that inside pitch for the third strike on Vosmik.”4

Kennedy said luck was with him and he praised Simmons for his diving catch on Galatzer’s smash.5

In his next start, Kennedy allowed four earned runs in six innings in a 6-2 loss to the Red Sox in Boston on September 8. In the final month of the season, Kennedy was 1-4 in September to finish the season with an 11-11 record and a 3.91 ERA. He completed 16 of his 25 starts. The White Sox, who had lost 99 games in 1934, improved to 74-78 in 1935. The White Sox were 60-56 on August, but lost 22 of their final 36 games to finish in fifth place.

The 1936 season, Kennedy’s second full season in the major leagues, was filled with highlights. He went 21-9 with career highs in starts (34), complete games (20), and innings pitched (274⅓), and was named to the American League squad for the All-Star Game. Kennedy was one of five players on the 22-player American League roster whom manager Joe McCarthy didn’t use in the National League’s 4-3 victory in Boston.

Kennedy earned his 20th victory on September 9. Pitching on three days’ rest, he pitched 13 innings to outduel Rube Walberg and Lefty Grove in a 3-2 victory over the Red Sox in Chicago. Kennedy allowed 10 hits and walked six (he walked a career-high 147 in 1936), but the Red Sox left 14 runners on base. Kennedy won his next start but lost his last two decisions and finished 21-9. The White Sox rose to third place with an 81-70 record.

On Opening Day of 1937, April 21, in St. Louis, Kennedy was roughed up by the Browns. He allowed 14 hits and 11 earned runs in 4⅓ innings in the Browns’ 15-10 victory. Kennedy regrouped to win three of his next four decisions and finished the season with a 14-13 record (and a career-high 114 strikeouts) as the White Sox improved to 86-68 with another third-place finish.

After the season, Kennedy was traded by the White Sox to the Detroit Tigers in a six-player swap. He was considered the key to the deal, which at least one writer call unpopular with the press and fans in Detroit.

“Opinion in Detroit is overwhelmingly one of protest against the trade. Here and there are defenders of (Tigers player-manager) Mickey Cochrane, who made the deal solely to get Kennedy, but a majority sentiment of press and public holds that the Tigers weakened the team in the wholesale shift,” wrote Sam Greene in The Sporting News.6

Kennedy got off to a good start with the Tigers. In his first start, against his former teammates on April 20, Kennedy pitched 6⅔ innings with no decision in a 5-4 loss to the White Sox in Chicago. But he went 10-4 in the first 2½ months to earn his second All-Star Game berth. As in 1936, Kennedy did not get into the game (in Cincinnati, won by the National League, 4-1). Kennedy was just 2-5 over the final 2½ months of the season to finish 12-9.

After a fourth-place finish (84-70) in 1938, Kennedy and the Tigers got off to a slow start in 1939. On May 13 in St. Louis, he took the loss in the Browns’ 5-3 victory. The loss dropped Kennedy to 0-3 and the Tigers to 7-15. After the game the Browns and Tigers completed a nine-player trade, which included both starting pitchers from the day’s game. Kennedy joined the Browns and among the four players received by the Tigers was Bobo Newsom.

Over the remainder of the 1939 season, Kennedy started 27 games for the Browns (with 12 complete games), winning 9 and losing 17. Including his 0-3 record in four starts for the Tigers before the trade, Kennedy finished 9-20.

On September 12 in Philadelphia, Kennedy, who was riding a four-game losing streak, allowed three runs to the A’s in the bottom of the first inning and was pinch-hit for in the top of the second. The 9-1 victory for the A’s was Kennedy’s 20th loss and dropped the Browns to 36-97. Three days later, Kennedy started and went eight innings in the Browns’ 9-5 victory over the Senators in Washington for his ninth victory of the season. The Browns finished the season with a 43-111 record.

The Browns and Kennedy showed improvement in 1940. He went 12-17 in 32 starts (18 complete games) as the Browns finished in sixth place with a 67-87 record.

Kennedy opened the 1941 season with three consecutive losses before winning two of his next three starts to improve to 2-4. On May 15, two days after the second anniversary of his trade to the Browns, Kennedy was sent to the Washington Senators in exchange for catcher Rick Ferrell. Kennedy went just 1-7 in 17 games (7 starts) for the Senators to finish the 1941 season with a 3-11 record. After the season his contract was purchased by the Cleveland Indians.

Kennedy went 4-8 for the Indians in 1942 (12 starts) but rebounded with a 10-7 record for the Indians in 1943 – his best season since 1938. He began the 1944 season with the Indians, going 2-5 in 10 starts. On July 28 his contract was purchased by the Philadelphia Phillies. Kennedy was 1-5 the rest of the season. On June 10, 1945, Kennedy (0-3 thus far) was traded to the Cincinnati Reds for rookie infielder Wally Flager.

Kennedy made what turned out to be his final major-league appearance on September 27, 1945, at the age of 38. He pitched eight innings and allowed three earned runs, in the Reds’ 7-4 loss to the Cubs in Cincinnati. The loss dropped Kennedy to 5-15 for the season – 5-12 with the Reds, who finished seventh with a 61-93 record. After the season, Kennedy pitched for a team of NL players who played an eight-game series against a group of AL players.

Kennedy went to spring training with the Reds in 1946, but was released on March 20 – his 39th birthday. But he wasn’t finished with professional baseball – he pitched in the minor leagues for nine more seasons.

After being let go by the Reds, Kennedy signed with the San Diego Padres of the Pacific Coast League. In 1946 he was 18-13 with a 2.92 ERA for team that finished 30 games under .500 (78-108). Kennedy returned to the Padres in 1947, going 9-15 with a 4.11 ERA (the Padres were 79-107).

Before the 1948 season the Padres traded Kennedy to the Hollywood Stars of the Pacific Coast League. At 41, he was 9-12 with a 3.93 ERA for the Stars, who were 84-104. In January of 1949, the Stars sold Kennedy’s contract to Dallas of the Texas League.

With a 6-4 record and a 2.54 ERA for Dallas, Kennedy was traded to the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association at the end of May. He told the Minneapolis Tribune, “I’ve had a pretty long career, (and) was ready to hang ’em up, but now I’d like to see it extended.”7

Even though he was in his 20th professional season, Kennedy said he was virtually the same weight when his career began. “In the 20 years I’ve been pitching,” he said, “I haven’t varied over three or four pounds from 175. I’ve always believed in clean living and I preach it to youngsters. Keeping in shape will do more to help a fellow than anything else.”8

Kennedy went 3-3 with a 7.15 ERA in 20 games, all in relief, with the Millers. Released after the season, he wasn’t ready to end his career. In early 1950, Kennedy advertised his services in The Sporting News:

“Ex-major leaguer, now a free agent, wants pitching job with Class AA or higher baseball league. Would consider job throwing batting practice in majors. Vernon Kennedy, Mendon, Mo.”9

Kennedy didn’t find a job in Organized Baseball in 1950. But in February of 1951, The Sporting News reported: “Vernon Kennedy, former big-league hurler who played with a St. Joseph (Mo.) semi-pro team last season, is returning to organized baseball this year as a relief pitcher for Oklahoma City (Texas League).”10

Kennedy, who had pitched for Oklahoma City in 1933 and 1934, spent the next three seasons with Oklahoma City. In 1951 he was 9-7 with a 2.64 ERA in 54 games and in 1952 he was 11-4 with a 2.23 ERA in 42 games. He pitched in the Texas League all-star game in 1952. In 1953 he was 4-4 with a 4.44 ERA in 44 games. All of his appearances were in relief except for one start in 1953.

Kennedy spent the 1954 and 1955 seasons with Beaumont of the Texas League. In 1954 he was 3-4 in 16 games. By opening the 1955 season with Beaumont, he became the oldest player in Texas League history. The Sporting News noted, “A check by Bill Ruggles, league statistician, has disclosed that pitcher Vern Kennedy of Beaumont is the oldest active pitcher in all league history. The ex-major leaguer observed his 48th birthday, March 20, making him one year older than Herschel (Jackie) Reid was when he last pitched for Shreveport and Fort Worth in 1941.”11

Kennedy was 1-1 in 14 appearances before being released by Beaumont at the end of May. In all, he had won 128 games and lost 129 in 14 minor-league seasons. For his 25-year professional career, he was 232-261.

But Kennedy still wasn’t done pitching. A month after leaving Organized Baseball, Kennedy pitched in an amateur game in which he was overshadowed by his daughter, according to The Sporting News, which wrote:

“Fifteen-year old Carol Kennedy proved a pitcher in the finest tradition in a one-inning relief appearance for the Salisbury (Mo.) Merchants against the Jefferson City Tweedies in Salisbury, June 28. The daughter of ex-major league pitcher Vernon Kennedy, Carol hurled the ninth inning and retired the side without being scored on to clinch a 10-3 victory. She walked two batters but caught the game-ending pop fly. Her dad, a veteran of 24 years in professional baseball, hurled the seventh and eighth innings and allowed one run.”12

Kennedy next spent 12 years teaching driver’s education in Missouri. In 1951 his alma mater, Central Missouri State, established the Vernon Kennedy Award, to be presented annually to the school’s outstanding male athlete. In 1954 Central Missouri named its football field Vernon Kennedy Field. In 1955 Kennedy was inducted into the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame and in 1992 he was a member of the inaugural class for the Central Missouri Athletic Hall of Fame.

Kennedy, 85 years old, died on January 28, 1993, in an accident at his home in Mendon, Missouri. The roof of a smoke-house he was dismantling collapsed on him, killing him instantly, according to the Chariton County coroner.13 The president of his alma mater called him “a remarkable man.”14

Kennedy was survived by wife Maud, a daughter, a son, two grandchildren, six-great grandchildren, three brothers and a sister.

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, milb.com, mosportshalloffame.com, Retrosheet.org, and ucmathletics.com.

Notes

1 Bill Dooly, “Mack’s New ‘Big Three’ – Mahaffey, Cain and Marcum!” The Sporting News, March 29, 1934: 3.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 “Enters Hall of Fame,” The Sporting News, September 5, 1935: 1.

5 Ibid.

6 Sam Greene, “Detroit Fans Deride Cochran for Swapping Walker to Dyke,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1937: 1.

7 Halsey Hall, “It’s a Fact,” Minneapolis Tribune, June 4, 1949.

8 Ibid.

9 The Sporting News, February 8, 1950: 24.

10 “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, February 21, 1951: 23.

11 “Rough Night for Mel McGaha,” The Sporting News, May 4, 1955: 31.

12 ‘Diamond Dust,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1955: 37.

13 Cathie Burnes Beebe, “Vern Kennedy Dies; Was Pitcher, CEMO Star,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, January 30, 1993.

14 Ibid.

Full Name

Lloyd Vernon Kennedy

Born

March 20, 1907 at Kansas City, MO (US)

Died

January 28, 1993 at Mendon, MO (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.