Al Atkinson

The Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association assembled in Philadelphia in early April of 1884. They welcomed four rookies, including pitcher Al Atkinson. The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote that the right-hander was “from an Illinois village and has his reputation to make as little is known of him.”1 He was quick to make an impression two days later by beating Yale 10-5 with 10 strikeouts. Exhibition games were played over the next three weeks and Atkinson showed enough talent to join the pitching rotation with Bobby Mathews and Billy Taylor. He got his first start on May 1 against the Pittsburgh Alleghenys. In front of 7,000 fans at the Jefferson Street Grounds, he limited the Alleghenys to seven hits and won, 9-2. A fair hitter, he added a single and scored a run.

The Philadelphia Athletics of the American Association assembled in Philadelphia in early April of 1884. They welcomed four rookies, including pitcher Al Atkinson. The Philadelphia Inquirer wrote that the right-hander was “from an Illinois village and has his reputation to make as little is known of him.”1 He was quick to make an impression two days later by beating Yale 10-5 with 10 strikeouts. Exhibition games were played over the next three weeks and Atkinson showed enough talent to join the pitching rotation with Bobby Mathews and Billy Taylor. He got his first start on May 1 against the Pittsburgh Alleghenys. In front of 7,000 fans at the Jefferson Street Grounds, he limited the Alleghenys to seven hits and won, 9-2. A fair hitter, he added a single and scored a run.

Pittsburgh got revenge two days later, besting Atkinson 9-8. He split a pair of decisions with Baltimore before beating Washington despite his own three errors. That started a four-game win streak highlighted by a no-hitter on May 24 against the Alleghenys. Pittsburgh did manufacture an unearned run in the first inning, but that was the extent of the damage in the 10-1 defeat. Atkinson issued only one walk, struck out two, and had two hits. It should be noted that pitchers in 1884 were not allowed to have their hand above their shoulder. Atkinson had a curve and a fastball in his repertoire. At the end of May, he had a 6-2 won-lost mark. Atkinson probably went from a one-day-a-week amateur pitcher to part of a rotation in the majors, taking the box every third game. Fatigue soon set in and in July he went home to rest from an illness.

Atkinson returned to the Athletics, but on July 24 he jumped to the Union Association. The Chicago Unions had been overworking One-Arm Daily and turned to Atkinson for help. Atkinson shut out Kansas City, 4-0, in his first outing, putting up a 4-4 record before the franchise was moved to Pittsburgh. There he went 2-6 before that team went belly-up and he was added to the Baltimore roster. With Baltimore, he added three more wins. He tossed 393⅔ innings in the two leagues. In the American Association, he was 11-11 and in the Union he went 9-15. He did finish in the top 10 in WHIP (walks and hits per inning pitched) in the Union at 1.051. His biggest deficiency was fielding; he made 31 errors for a .785 fielding percentage.

Atkinson was born in Clinton, Illinois, on March 9, 1861. His mother was the former Mary E. Wright; the identity of his father is unknown. The Wrights had moved west from New York, through Pennsylvania, where Mary was born, before settling in Illinois. In 1870 Mary and Al lived with her mother and brothers in Mount Pulaski, in central Illinois. She worked as a milliner. Atkinson got four years of elementary-school education before going to work as a farm laborer.

Central Illinois was a hotbed for baseball. Peoria and Springfield fielded minor-league teams in the 1880s when few leagues existed. Newspaper coverage of baseball was also in its infancy, so when and how Atkinson was discovered is a mystery. He is listed as 5-feet-11 and 165 pounds.

Atkinson was blacklisted for his jump to the Union Association. He was eligible to return contingent upon re-signing with the Athletics. He seemed content to return to Illinois instead and play semipro ball. There was one report that Milwaukee of the Western League might try to get him reinstated.2 No deal ever materialized and Atkinson joined the Gem City club in Quincy, Illinois, before moving to St. Joseph, Missouri.3 He may also have played for a team called the Chicago Blues. In October, he agreed to terms with Philadelphia and was reinstated for the 1886 season.

After tending bar all winter, Atkinson joined the Athletics in late March of 1886. The highlight of their training season was a seven-game series against the Phillies of the National League. Early in the regular season the Athletics used four pitchers: Bobby Mathews, Ted Kennedy, Sam Weaver, and “Atkisson.” Weaver was jettisoned quickly after allowing 30 hits in 11 innings. Kennedy posted a 5-15 mark before his release. Atkinson, who appeared in print as Atkisson for most of the season, won his first two starts and took the box on May 1 against the New York Metropolitans. A first-inning error led to a run for the Mets, but Atkinson walked and scored in the third to knot the score. He took a 3-1 lead into the ninth when a two-base error, a grounder, and a fly scored a second run for the Mets. Atkinson slammed the door and recorded his second no-hitter in the process. The next day Mathews allowed 22 hits and 19 runs against Brooklyn. Atkinson took over as the ace of the staff.

Atkinson was the first American Association pitcher to toss two no-hitters. Adonis Terry of Brooklyn duplicated the feat in 1888. Larry Corcoran of the Chicago White Stockings in the National League had three no-hitters from 1880-84 which might explain the lack of excitement about Atkinson’s feat. He went on to compile a 25-17 record in 396⅔ innings, nearly 200 fewer than league leader Toad Ramsey of Louisville. He led the league in hit batters (22) and home runs surrendered (11). Once again overwork wore Atkinson down and he ended the season when “the Cincinnatians pounded the life out of Atkisson today.”4 He returned to St. Joseph and the saloon business uncertain about his future. In late November, the Athletics finally decided to reserve him for 1887.

The Athletics and Phillies opened the exhibition season in April. The Athletics tested Atkinson and were pleased with the results, especially a four-hit shutout on April 12. They opened the season with a two-man rotation of Ed Seward and Atkinson.

Atkinson lost to Baltimore, but then beat the Mets and Ed Cushman twice. Curiously, he saw no action for the next 18 days as Cannonball Titcomb and rookie Gus Weyhing joined Seward in the rotation. When he took the box on May 14 the Inquirer called him Atkinson, but soon reverted to calling him Atkisson for the remainder of the season. He won on the 14th, besting Louisville in 10 innings. Seward and Weyhing were given the bulk of the work. Atkinson was used on doubleheader days and when there were three games in three days. This meant that he would often sit a week or more between starts. On August 10 and 13 he lost consecutive games, surrendering 13 runs in each. The Athletics released him. Weyhing and Seward pitched over 900 innings; Atkinson made 15 starts and tossed 124⅔ innings with a 6-8 record.

Atkinson’s major-league career was over. He had a 51-51 record and a 3.96 earned-run average.

Atkinson returned to Missouri, but soon joined the Lincoln (Nebraska) Tree Planters in the Western League. Former Athletics Orator Shaffer (his box-score name, Baseball-reference uses only one “f”) and Bill Hart were members of the team. Atkinson had a 2-2 mark with Lincoln. In 1888, he went north to join the Toronto Canucks in the International Association. For the first time in his career, he was in a league that was not dominated by powerful hitting. The Canucks and Syracuse staged a great pennant race until Atkinson fell ill in September and Syracuse pulled away to win by 3½ games. Atkinson compiled eye-popping statistics. He hurled 444 innings, second in the league, and his 34-13 record was the fourth highest wins’ total. He finished second in ERA and WHIP and led the league with 307 strikeouts, nearly double his competition. He also hit .219, a career high for him in a full season. Atkinson was well compensated for his work. He was signed for the maximum salary allowed but manager Charlie Cushman “engaged his wife and other relatives as clerks, stenographers, etc. so as to make up the salary he wanted.”5 None of the relatives was ever put to work. There is one other reference to Atkinson being married during the 1880s. Because the 1890 census was destroyed by a fire, the name of his spouse is uncertain.

As in past seasons, the 1889 Canucks went to Cincinnati in April for exhibition games with the Reds. Atkinson was so wild in his first outing that he was yanked early. The poor pitching haunted him into the regular season. In 30 innings he issued 20 walks, hit four batters, and unleashed eight wild pitches. It is uncertain whether this is related to his illness or was a case of “Steve Blass disease,” but his career was essentially over. He played a game with Toronto in 1890 and then five games with Rochester in the Eastern league in 1892. There were rumors that Atkinson might have been considered as manager for the Canucks in 1890, but nothing materialized.

Leaving his baseball career behind, Atkinson moved to McDonald County, Missouri. He worked in the lead and zinc mines. He also did carpentry work on the side. Eventually he purchased farmland near McNatt and raised grain. In 1903, he wed Nancy Jane (Wasson) Paschall, a divorcee with two children, Forest and Agnes. The marriage lasted until Nancy’s death in 1951. They helped to raise both of Agnes’s children, Wincel and Glenn Pogue, and Al kept farming into his 80s.

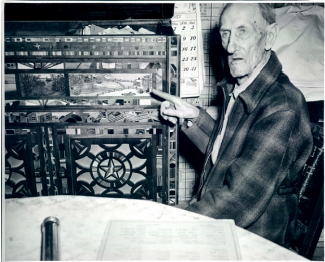

Atkinson gained local notoriety in the late 1920’s and 1930’s with his artwork. Most notably was a piece he called “Star of America.” He had heard on the radio that there was a contest with a $500 prize for the best radio console. He created a magnificent piece made from over 15,000 pieces of wood from 72 different, native Ozark woods. The effort took nearly two years to complete. As fate would have it, he did not enter the contest because of the entry fee. The console was displayed locally and gained attention. It went on display at the Missouri Museum in Jefferson City for about a dozen years.6

In addition to his carpentry, Atkinson became a self-taught painter and created landscapes and portraits. His reputation grew and he was even interviewed by The Sporting News in 1951. He died in his McNatt, Missouri, home on June 17, 1952. He and Nancy are buried in Macedonia Cemetery near Stella, Missouri.7

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted The Baseball Encyclopedia, Atkinson’s player questionnaire at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the Baltimore Sun, Daily Illinois State Journal (Springfield, Illinois), New York Herald, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Philadelphia Times, and The Sporting News.

Notes

1. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 5, 1884: 2.

2. Kansas City Times, May 5, 1885: 2.

3. Sporting Life, June 3, 1885: 7.

4. Sporting Life, October 11, 1886: 2

5. Omaha World-Herald, May 15, 1892: 13.

6. “True History of an Ozark Radio Console,” Neosho Daily News (Neosho, Missouri), December 28, 1929: 4.

7. Joplin (Missouri) Globe, June 18, 1952: 6.

Full Name

Albert Wright Atkinson

Born

March 9, 1861 at Clinton, IL (USA)

Died

June 17, 1952 at McNatt, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.