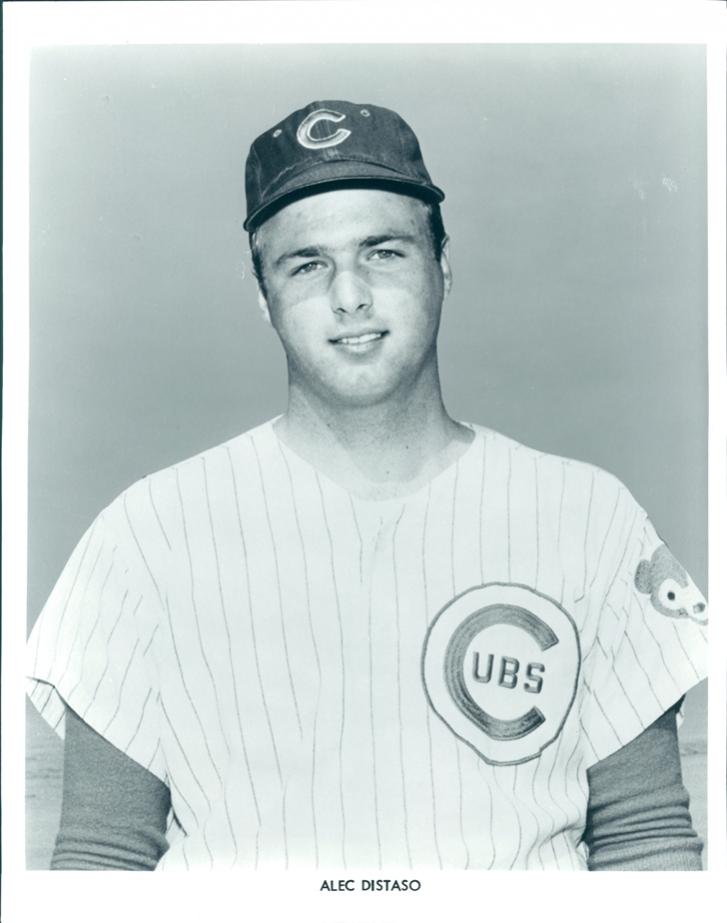

Alec Distaso

For Alec Distaso, pitching was a prelude to helping his fellow man. The righty made only two major-league appearances with the Chicago Cubs in April 1969, but he spent over 30 years providing two basic human needs. As a policeman, he offered safety; as a public housing administrator, he gave shelter. He also served his nation for six years in the Army Reserve.

For Alec Distaso, pitching was a prelude to helping his fellow man. The righty made only two major-league appearances with the Chicago Cubs in April 1969, but he spent over 30 years providing two basic human needs. As a policeman, he offered safety; as a public housing administrator, he gave shelter. He also served his nation for six years in the Army Reserve.

The Los Angeles native was the #1 overall pick in the January 1967 draft and drew comparisons to Don Drysdale.1 Sad to say, the Cubs did not protect their investment. Weeks after going from the majors to Double A ball for seasoning, Distaso hurt his elbow. Both when he got injured and after, the reward of usage didn’t warrant the risk. In less than two years, aged just 22, his pro baseball days were over.

Distaso then went from pounding the strike zone to pounding the beat. He joined the Los Angeles Police Department, where he became a training officer and later a detective. After retiring from the force, he launched his third career in rural Illinois. As with baseball, though, this man’s time on earth ended too soon. He passed away in 2009 at age 60.

Alec John Distaso — he preferred “Al”2 — was born on December 23, 1948. He was the oldest of three children born to Biaggio and Geraldine (née Green) Distaso. Al had a brother named Mark and a sister named Doreen.

An impressive high-school pitcher, Distaso first attended Garfield High in East Los Angeles. As a junior in 1965, Al was 5-1 while the team was 6-4 overall. He was a third team All-City selection.3 After that, Al went to another school in East L.A., Woodrow Wilson High. Both had respectable baseball programs, but the Wilson Mules have sent at least one other man to the majors: pitcher Victor Bernal, who appeared in 15 games for the San Diego Padres in 1977.

In 1966, the Cubs finished with the worst record in the majors. Thus they received the top pick in the January phase of the 1967 amateur draft. The AL cellar-dweller, the Yankees, chose first in the June phase. The January phase, which was eliminated in 1986, was for high school and college players who graduated in the winter. That winter, Al also played semi-pro ball with the “Angel Rookies” team in the Scout League, the top bracket of the Southern California Baseball Association Winter League.

“Distaso, a 6-foot-2, 185-pounder who is graduating high school, got the highest marks on the Cubs’ scouting reports, according to farm director Gene Lawing. ‘We received good reports on him from our two men in Los Angeles,’ Lawing said. ‘We consider him the top player available at this time. We’ve seen him in previous years and we liked him then too.”4 The men recommending Al were Gene Handley, Chicago’s longtime supervisor of West Coast scouting, and Gordon Goldsberry, who later became director of the minor leagues and scouting for the Cubs in the 1980s.

Only three other first-rounders from that draft made it to the majors for long: a Hall of Famer in Carlton Fisk (#4, Red Sox), a solid star in Ken Singleton (#3, Mets), and a journeyman pro in Von Joshua (#17, Giants). The January crops always had fewer total players than June, and historically they were thinner in talent too.

Ten days after the draft, on February 7, Distaso signed with the Cubs. The top pick began the 1967 season with Lodi in the high Class A California League. Eight men from that pitching staff would go on to the majors, most notably Jim Colborn. That May, the Nevada State Journal singled out three of them whose grand total in The Show was just five games: “[Jophery] Brown, Distaso, a bonus rookie, and former Santa Clara frosh star Pat Jacquez are the fastest of the Crusher moundsmen.”5

Wildness marked a rather rough start for Al, though — 43 walks in 52 innings led to a 2-4 record and a 5.02 ERA. Perhaps his best effort came in a tough loss at home against Fresno on May 9. Future Milwaukee Brewer Gary Ryerson threw a one-hitter and faced the minimum 27 batters. “He had to be sharp last night to best Distaso,” wrote the Fresno Bee. The game’s only run came in the fourth inning as Al and teammates gathered around a slow roller down the first base line. The ball stayed fair and a runner scored from second base.6

On June 22, Distaso was fortunate to escape serious injury. He took a line drive to the forehead, just over his right eye, in a game at Fresno. “The game was delayed 14 minutes as the Lodi hurler sprawled on the mound, waiting for an ambulance. An examination at Community Hospital proved negative and the tall Lodi pitcher was on his way back to John Euless Park before the game was completed.”7

A few days later, the Cubs sent Distaso to the Pioneer Rookie League. The Lodi News-Sentinel wrote, “Distaso showed up well on occasion but lacked consistency.”8 With Treasure Valley in Caldwell, Idaho he did better (3-2, 3.64), and he won promotion in mid-August to Quincy, Illinois in the Class A Midwest League. The learning process continued (1-3, 5.40). The most encouraging sign was improved control (37 walks in 72 innings at Caldwell and Quincy).

Distaso enjoyed his greatest success as a pro with Quincy in 1968. He made 25 starts and relieved six times, leading the Midwest League with 13 wins. He lost eight, including just one of his last nine decisions, a streak that brought his ERA down to 3.30. He pointed to the addition of a change-up, saying, “That’s what it’s all about, keeping the hitters off stride.”9 Near the end of the season, he jumped to Triple-A Tacoma (0-2, 2.08). His control stayed about the same, with 93 walks in 182 total innings.

Distaso’s strikeouts were notable: 225 in 306 innings over his first two years in the chain. He further impressed the Cubs with his 3-0, 1.73 showing in the Arizona Instructional League that fall. In October, Chicago reassigned three big-leaguers (Chuck Hartenstein, Jack Lamabe, and Bob Tiefenauer) to the minors. Distaso and four other pitchers were added to the Cubs’ 40-man roster.10

Over the winter, manager Leo Durocher mentioned Distaso as a candidate for long reliever on the big club in 1969.11 Among other things, Leo was not a fan of Joe Niekro and his knuckleball. “It appeared that Durocher was always looking for reasons to get Niekro off the roster. . .To this end Durocher promised rookies Jim Colborn, Joe Decker, Archie Reynolds, Alec Distaso, and Dave Lemonds long looks in Arizona in March.”12

Spring training 1969 was entertaining at times. In one exhibition game at Scottsdale on March 19, umpire Doug Harvey refused to give Al a new ball when he asked for one. “Durocher grabbed the ball from Distaso, rubbed dirt on it and then threw it into the stands. Harvey promptly tossed out Durocher.”13

That month, the Chicago Tribune described Distaso as a “rookie who is most impressive. . .using a sharp curve ball with the poise of a veteran.”14 Baseball Digest offered this scouting report: “Definite major league prospect but must be tested in high minors. Good speed and good curve, but control only fair.”15 Cubs pitching coach Joe Becker and Fred Martin, then their roving pitching instructor in the minors, helped Distaso sharpen his curve. He also worked on making his fastball sink.16

Even though he had pitched not even a game in Double A and only three at Triple A, the 20-year-old emerged from the pack with his mental and physical ability. “You don’t have to hit him over the head,” said Becker. “All you have to do is tell him once.” Al’s competitiveness, as well as a facial resemblance, then also won him the Don Drysdale comparisons. “He wishes the resemblance went further,” Chicago sportswriter Jerome Holtzman noted. “Said Distaso: ‘I wish I was as big as he is — and had his fast ball.’”17

Al made the Cubs staff as the tenth man and sole rookie. Durocher said (in a dig at Ken Holtzman), “The kid’s got the courage of a lion. He really shows me something.”18 He later added, “If there is a fifth starter it would probably be the kid.”19 This was something of a surprise because Leo’s view on young players was ambivalent. Over his career, he backed certain rookies, notably Willie Mays. Yet looking back on the 1969 season, Cubs reliever Phil Regan said, “Leo didn’t like young guys.”20

Wearing number 45, Distaso made his big-league debut on April 20 in the second game of a doubleheader at old Jarry Park in Montreal. Relieving Joe Niekro, who took the loss, Al retired six of the seven Expos to face him, allowing just one walk. His only other appearance came two days later, at another park of yesteryear, Pittsburgh’s Forbes Field. Bill Hands got knocked out in the second inning, and Distaso allowed two inherited runners to score before retiring the side. He then gave up two runs of his own in the fourth before leaving for a pinch-hitter.

On May 10, the Cubs promoted catcher Bill Heath from Tacoma and sent Distaso down to San Antonio in the Texas League (Double A). The team went with just nine pitchers; “it was decided that this number would suffice with the team encountering seven off days in the next four weeks, and with the batsmen currently suffering.”21

Although Distaso liked to talk baseball, he talked little about himself. His only known comments on his time in the majors were terse. It would have also been intriguing to hear his observations of figures such as Leo Durocher, Ernie Banks, and Ferguson Jenkins.

Down in San Antonio, Distaso dropped his first two decisions but then pitched a commanding eight innings for his first win on June 7. He left the game in order to catch a flight for military duty.22

Distaso returned from his reserves service in just over a week and picked up right where he left off. He got three complete-game wins (although one was a seven-inning job in a doubleheader) against one well-pitched loss. According to Q.V. Lowe, a fellow pitcher at Lodi and San Antonio, Distaso “threw hard, but his mechanics were a little rough. Fred Martin worked with him to shorten his stride.” As a result, Al wasn’t blowing batters away, but his walks were way down and the hit totals were low too.

Then, coming out of the bullpen on July 11, he got hurt. “Distaso. . .has been sent to Chicago for examination of an extreme swelling in his right elbow. The injury came to light Friday night in Memphis, when Distaso was able to pitch to only two men [actually just one, with a wild pitch and a passed ball] before being pulled from the game.”23

Though we do not know what Distaso said or felt when it happened, a professional view is available from someone who was there: Q.V. Lowe, a coach in the pro and college ranks for 40 years. While pinpointing a cause of injury is not truly possible, he agreed that even by 1960s standards, the way the club used its prospect was debatable.

Two nights before the abortive relief outing, Distaso had started, giving up 12 hits and walking one in six innings. Although Lowe did not recall that part, he commented that relieving between starts “definitely was not policy. He could have been up around 140 pitches in that start too.” Friday the 11th was Distaso’s “throw day,” so relieving was not out of the question — if the payoff was there. What exactly was at stake?

When manager Jim Marshall brought Distaso in for Jophery Brown that Friday, it was a “fireman” situation: bases loaded, two out in the seventh inning, and San Antonio up 6-4. The slumping Missions had a 36-43 record, last in the Eastern Division, yet still only 3 1/2 games behind first-place Memphis and one back in the loss column. Even so, they were rolling the dice merely for a berth in the Texas League playoffs. Alas, the move backfired in every way. The Missions lost the game and more.

Things went from dubious to deplorable. Less than two weeks after his exam, Distaso returned to the mound. He threw five sharp innings in relief but slumped after that, losing five straight to end at 4-8, 4.21. No doubt still hurting, he did not get back to Chicago. In today’s game, management would have shut him down earlier — if not immediately. Meanwhile, San Antonio tottered to a 15-38 finish.

It’s quite likely that Distaso was a candidate for Tommy John surgery. Unfortunately for him, the procedure was still five years away, and MRI tests were even further in the future. Without such diagnostics and treatment, “teams would just try to get all they could out of a player then,” said Q.V. Lowe.

The Sporting News Baseball Register still had an entry for Distaso (whose hobby was playing pool) in its 1970 edition. After a four-month hitch in the Army, he rejoined San Antonio in May. He got off to a very rocky start (0-3, 14.14), as he walked 19 men and allowed 27 hits in 14 innings. The Cubs sent Distaso to Quincy in late June; there he righted himself, winning all four of his starts with a 1.29 ERA. Upon earning promotion to Tacoma in August, though, things went sour again (0-5, 16.71) as he was shelled for 37 hits in 14 innings.

Distaso gave it one last try in 1971. On February 23, the Chicago Tribune reported that the Cubs had given him informal permission to join the team’s workouts in Mesa, Arizona. Distaso, who then lived in nearby Scottsdale, was still on the Tacoma roster.24 Later that spring, he pitched with San Antonio in the exhibition season, but it didn’t work out. Q.V. Lowe, who had become the Missions’ pitching coach in 1970 while remaining an active player, said, “I remember him struggling with the elbow. I think he just walked away because he couldn’t do it any more.”

After leaving baseball, Distaso joined the LAPD. Back then the hiring process took anywhere from six to 12 months, including police academy training. Distaso was appointed to the department on December 27, 1971.

Retired Sergeant Jon Reese remembered those days. “I came on the job in 1973 and Al came on in 1971, so he was established at Southwest Division in patrol when I arrived as a rookie. Being senior to me, he was a training officer. Although he was not my assigned partner, we worked together several times. As a new officer, I was truly impressed with Al’s professionalism while on duty. Not only that, it was fun working with a guy with a quick wit and a positive outlook. I learned a lot from Al.”

Distaso transferred to the Valley Bureau and (at some point after 1979) took the next step up the LAPD ladder from Police Officer III. Jon Reese surmised that Al may have entered the P-3 Detective Trainee program. “That was and is a type of loan for patrol guys to Detectives.”

After he became a detective, some of the cases Distaso handled were exactly the kind of thing that fueled Joseph Wambaugh’s novels about the LAPD. In the summer of 1986, a man named Thomas Lee Larsen struck over 300 cars and five people with an acid spray in a wide-ranging series of attacks. Distaso described the damage in Devonshire Division, his station at the time.25 The spree investigation went to a special undercover task force called COBRA Corps that took on major crimes too big for separate LAPD divisions. This team finally arrested the “Acid Sprayer” late that July.26 27 It was neither the beginning nor the end of Larsen’s disturbing criminal history.28

Almost a year later, Distaso made the L.A. papers again after a brawl in the parking lot of an Alpha Beta grocery store in Granada Hills. He and his partner, William Vaughan, were working undercover on a different case when they happened upon the fight and called for patrol cars to back them up. About 20 boys and young men described as “middle-class Valley boys” were involved in the fracas, some armed with baseball bats and poles — one even had an ax. Vaughan chased the man with the ax but momentarily lost him. Distaso, after throwing a man with a bat against a pickup truck, tried to handcuff him, but another man jumped him from behind. The man with the ax reappeared, approaching Distaso with the weapon raised. Vaughan then suffered a blow to the head after he fired his service revolver at the ax-wielding man. He was hospitalized with a concussion, while Distaso was treated for injuries and released from an emergency room.29 30 31

As of 1989, Distaso worked out of Rampart Division,32 the gritty location of cop movies (Colors) and TV series (The Shield). He was in the homicide unit. Another detective named Chuck Salazar recalled, “We worked Rampart Homicide during the L.A. riots at a time when Rampart was the murder capital of the city.”

His colleagues held Distaso in high esteem. When Salazar learned that Al had played for the Cubs, he and his partner scoured the hobby shops for months to buy a copy of the pitcher’s 1969 Topps rookie card for every man in the unit. At his retirement from the LAPD in 1994, his fellow officers presented Distaso with a framed 18” x 24” blowup of the card. In his honor, they also kept another enlarged copy at Rampart Detectives.

Distaso was married to Kim Cunningham, a nurse, for a little over 20 years. Their sons Douglas and Brian both pitched (and played football) at William S. Hart High School in the Newhall district of Santa Clarita, California. Doug was an All-Foothills League selection in center field as a junior. As a senior, he then switched to third base and finally became a pitcher. Doug went on to the U.S. Air Force Academy and earned major’s rank in 2005. Brian continued to pitch in junior college and then at Illinois State University.

In 1995, the Distasos moved to Kim’s hometown, Macomb, Illinois, about four hours’ drive southwest of Chicago. (Not long after, they were divorced.) Macomb is also just a little over an hour northeast of Quincy, where Al had played for parts of three seasons in the minors. Jimmy Qualls, with whom Distaso and outfielder Don Young shared that rookie card, lives just north of Quincy in the village of Sutter. Jim and Al were teammates at Lodi and Tacoma as well as their brief time together with the Cubs. “A few years ago I was going through Macomb,” Qualls recalled in 2010. “A friend told me he was there. We talked a couple of times on the phone, and he told me about a trip he made to Mexico, but we never did get together.”

In 1996, Distaso joined the Housing Authority of McDonough County (Macomb is the county seat). The authority’s executive director, Bill Jacobs, wrote, “[Al’s] police experience was a strong factor” in his decision to hire Distaso as a development manager. “We needed a person who could meet the challenges of the criminal elements that were present in our apartments and sidewalks.” Jacobs observed Distaso’s calm, smiling, easy way with people. “You couldn’t get a rise out of him.”33

Distaso later became Admissions Manager, processing applications for public housing and the Section 8 Voucher Program.34 The latter is a program run by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development that allows very low-income households to choose privately owned rental housing. Distaso conducted all briefings for new participants.

According to Bill Jacobs, Al Distaso was a private man who shunned the baseball spotlight, yet he was a friendly and well-liked figure in the community. Distaso was a member of the Macomb American Legion Post 6 and Macomb Elks Lodge #1009. He was also an avid golfer.

After becoming gravely ill with cancer, Distaso passed away at McDonough District Hospital on July 13, 2009, surrounded by loved ones. His family chose cremation. Distaso’s obituary stated, “He offered camaraderie unconditionally, recognized friendships everywhere and never passed judgment without personally experiencing wrong. Al showed us how to treat others without exceptions and no matter the conundrum, charted the ideal solution.”

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Distaso family, Q.V. Lowe (Head Baseball Coach, Auburn University at Montgomery), Jon Reese, Bill Jacobs, and Jim Qualls.

Sources

Al Distaso obituary, Macomb Eagle/Peoria Star, July 15, 2009

Dodsworth-Piper-Wallen Funeral Home, online guestbook

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.probaseballarchive.com

www.thebaseballcube.com

www.garfieldhs.org

www.mcdonoughhome.org

www.hud.gov

Photo Credits

Mark Fricke collection

2 Distaso is the only man with the given name “Alec” to reach the majors. It was often wrongly written as “Alex.”

3 “Helms Selects Lentine City Player of Year.” The Valley News (Van Nuys, CA): June 8, 1965: 28. At least three other future major-leaguers were visible: pitcher Tom Griffin (1969-82) was on the second team, as was Randy Bobb, then a pitcher. Bobb later became a catcher with the Cubs, was briefly a teammate of Distaso’s in the minors, and got cups of coffee with Chicago in 1968-69. Ken Poulsen, who appeared briefly with the 1967 Red Sox, was on the third team with Distaso.

4 Chass, Murray. “Varney, DiStaso Lead Draft Picks.” Associated Press, January 29, 1967.

5 Landell, Gib. “High-potential Crushers Invade Moana Tonight.” Nevada State Journal, May 26: 1967: 11.

6 “Fresno’s Ryerson One-Hits Lodi.” Fresno Bee, May 10, 1967: 1-D.

7 Betterton, Terry. “Fresno Kayoes Lodi Hurler In 12-7 Romp.” Fresno Bee, June 23, 1967: 18.

8 “Distaso of Crushers Is Farmed Out.” Lodi News-Sentinel, June 26, 1967: 16.

9 Holtzman, op. cit.

10 “Chicago Shifts Fifteen Players.” Associated Press, October 17, 1968.

11 Sainsbury, Ed. “Cubs Acquire Ted] Abernathy To Aid Bull Pen Corps.” United Press International, January 10, 1969.

12 Feldmann, Doug. Miracle Collapse: The 1969 Chicago Cubs. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2006: 41.

13 “Cleveland Is Halted.” United Press International, March 20, 1969.

14 Langford, George. “Cubs Lose to Padres and Podres.” Chicago Tribune, March 16, 1969: B1.

15 “Official Scouting Reports on 1969 Major League Rookies.” Baseball Digest, March 1969: 19.

16 Holtzman, op. cit.

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid. Jerome Holtzman later noted, “At that time, Leo the Lip didn’t want to say anything flattering about [Ken] Holtzman. Instead, Durocher, as he often does, switched the conversation.” See “Lippy’s Blasts Turning to Bravos for Ken Holtzman.” The Sporting News, June 7, 1969: 4.

19 Langford, George. “Cubs Beat Giants, Then Shuffle.” Chicago Tribune, March 29, 1969: A3.

20 Hayes, Neil. “Fast rise, fast to exit for former Cub pitcher.” Chicago Sun-Times, May 15, 2008. Subject: Darcy Fast.

21 Feldmann, op. cit.: 103.

22 Evans, Ray. “Missions Rap Blues, 4-2, Behind Al Distaso.” San Antonio Light, June 8, 1969: 36.

23 “Quincy Ace Joins Missions.” San Antonio Express and News, July 13, 1969: 2-S.

24 Langford, George. “Fergie May Still Get $100,000.” Chicago Tribune, February 23, 1971: B5.

25 “Man Spraying Cars, People With Corrosive Chemical.” Los Angeles Daily News, June 11, 1986.

26 “Van Nuys Man Held In Spraying Of Acid.” Los Angeles Daily News, July 31, 1986.

27 Henry, Mark. “Task Force Arrests ‘Acid Sprayer’ Suspect.” Los Angeles Times, July 31, 1986: 7.

28 More detail is not relevant to this story but can be found by searching under “Fedbuster.”

29 “2 Officers Injured in Fracas.” Los Angeles Daily News, June 4, 1987.

30 Fuentes, Gabe. “Officer Injured in Fight After Shooting to Protect His Partner.” Los Angeles Times, June 4, 1987: 9.

31 “Brawler Is Sought For Hitting Officer.” Los Angeles Daily News, June 6, 1987.

32 “Where ’69 Cubs Are.” Chicago Sun-Times, July 17, 1989: 4.

33 Grass Roots (The Official Newsletter of the Housing Authority of McDonough County), Volume 10, Number 8: August 2009.

34 Grass Roots (The Official Newsletter of the Housing Authority of McDonough County), Volume 5, Number 5: May 2004.

Full Name

Alec John Distaso

Born

December 23, 1948 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

July 13, 2009 at Macomb, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.