Alfred Henry Spink

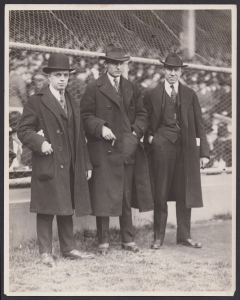

From left, Sid Mercer of the New York Journal, Al Spink of The Sporting News, and G.W. Axelson of the Chicago Herald. (Photograph by Charles Martin Conlon of the Chicago Herald.)

The irony is clear to anyone who gives it even the slightest thought. At the time that baseball was entering the public consciousness in the United States, emerging as the national pastime, one of the central figures in that development was a Canadian-born entrepreneur and sportsman, Alfred H. Spink. As a sportswriter and unflagging baseball booster, Spink not only helped embed the game in the American psyche, but he also created and developed the newspaper, The Sporting News, that would eventually, and deservedly, earn the title the “Bible of Baseball.”1

Alfred H. Spink was born on August 25, 1852 (some sources say 1853 or 1854), in Quebec City, Canada.2 He was the third of four sons and one of the eight children born to William and Frances Anne (Snaith) Spink.3,4 William served many years as a records clerk in Quebec’s legislative assembly.5 After his death in February of 1867, the family emigrated south from their native Canada, presumably in search of better employment opportunities in post-bellum America. Settling on the west side of Chicago, the growing boys, all one-time cricket enthusiasts, quickly adapted to the developing game of baseball, one well on its way to being crowned America’s national pastime.6 Indeed, once they were old enough, the Spink boys joined the roster of one of the Windy City’s most prominent amateur teams, the Mutuals (some sources credit the brothers with being central figures in the team’s creation),7 named for a famous squad in New York City whose major financial backer was the infamous New York political leader Boss Tweed.8

With their father dying not long after the family moved to the United States, the boys had to help with family responsibilities. The oldest, William, known as Billy, did a stint as a telegraph operator before eventually going into journalism. Alfred too went in that direction as a way to stay involved with the game that had captured the older boys’ interest upon their arrival in the United States.9 In 1875 Alfred left Chicago and moved south to follow Billy, who was then working for the St. Louis Globe-Democrat.10 According to Al, Billy was a trailblazer, persuading the paper’s editor to add sports coverage to its offerings. While Billy was initially a virtual one-man sports bureau, it was apparently a natural fit, since in Al’s view his older brother was “the best all around sporting writer of the day, if not the best all around sporting editor that ever lived.”11

While Al joined his pioneering brother Billy in St. Louis, he initially worked for the Globe-Democrat’s rival, the St. Louis Post. However, just about the time Al started working there, newspaper mogul Joseph Pulitzer merged the Post with the Globe-Democrat. Not long afterward, Al left the paper, eventually serving as sports editor of first the Missouri Republican and then the St. Louis Chronicle.12

While Spink’s work as a journalist was generally focused on sports, as a young reporter he displayed an adventurous streak that was nowhere better illustrated than in his foray into Grenada, Mississippi, in 1878, in the midst of a yellow fever epidemic. Taking leave from the Globe-Democrat to serve as special correspondent for the New York Herald, Spink recounted the veritable decimation of the town of Grenada. He wrote of a town so paralyzed with fear that no one would even venture to retrieve the body of one who was a victim of the disease ravaging both the bodies of countless inhabitants and the psyches of those physically untouched. He told of seeing bodies being taken directly from the site of their death to the cemetery, so as to reduce possible contact with the dead body and the disease. So fearful was the community, and so contagious was the disease believed to be, that Spink reported that had he actually entered the town of Grenada, he would have been unable to enter any of the towns down the road. It was a time of fear and anxiety, a reality brought home by the fact that upon the outbreak of the disease Grenada was a community boasting a population of 2,500. However, once the fever arrived all but about 250 Whites fled the town; almost all of these were affected, with over 125 dying. It was devastating. Spink noted that the fever did not discriminate, for of the almost 80 Blacks who were hit by the disease, about half of them died as well.13

That experience revealed a different side of Spink, whose reporting on the human tragedy exhibited an impressive empathy, as well as an ability to make the larger issues come alive through his depiction of the many individuals who suffered. His report of burning his own clothes and personal effects as he left Grenada brought home both the personal nature of the plague but also the extent of its impact: after speaking of the conditions that were “simply beyond description,” he made clear that he knew he was one of the lucky survivors.14 Fortunately, such ventures were aberrations for the young man who had grown up with a cricket bat in his hand, but had easily transferred that experience into a passion for the game of baseball; in spite of a few detours by the sometimes mercurial Spink, baseball remained a central part of his life until his death in 1928.

Both Al and Billy used their positions as sports editors to boost the fortunes of the city of St. Louis and its professional baseball teams. This was a particularly important undertaking in the aftermath of a widespread gambling scandal in 1877 that led the leaders of the city’s National League entry, the Brown Stockings, to withdraw from the league.15 Their efforts were rewarded in 1880 when they persuaded Chris Von der Ahe, a German immigrant saloonkeeper often credited with forging the bond between beer and baseball, to sponsor a new team.16

Having appealed to his vanity, convincing him that his involvement would lead to local prominence and fame, in the fall of 1880 the Spinks got Von der Ahe to assume the role of president of the newly formed Sportsman’s Park Club and Association. Al Spink was selected as secretary. Backed by the infusion of funds that Von der Ahe’s involvement brought to the enterprise, the association quickly set about renovating Sportsman’s Park. At the same time, under the auspices of the St. Louis Baseball Association, Al, his brother William, and Ned Cuthbert were organizing the latest version of the St. Louis Browns, a team that would play in Sportsman’s Park – where Von der Ahe had the concession rights. Playing an independent schedule intended to revive interest in the game in St. Louis, the team was a resounding success. By the end of the summer the new St. Louis Browns were taking on all challengers, and the large crowds made Von der Ahe a lot of money. Indeed, so successful was the whole enterprise that at year’s end, the savvy German immigrant, having come to the realization that “baseball was an excellent adjunct to his grocery and saloon business,” effectively bought the team, incorporating it into the Sportsman’s Park Club and Association.17

Next came the creation of a league for the team to play in. After discussions and negotiations in the fall of 1881, a six-team American Association of Base Ball Clubs was formed. The six cities were St. Louis, Louisville, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Baltimore. While the established National League, part of whose mission was to fight the evils of both drinking and gambling, dismissed the new group as the “Beer and Whiskey Circuit,” they also quickly realized that the new association represented a very real competitor, and no team was more successful than the Browns.18

Over the next few years baseball underwent a renaissance in St. Louis. Fueled by Von der Ahe’s funds and Spink’s public relations know-how and baseball acumen, the team thrived. While officially the Association secretary, Spink performed a number of roles with the Browns, including serving as both the secretary and press agent for the new franchise. He is generally credited with helping assemble the team that won four straight American Association pennants beginning in 1885.19 While his fingerprints may have been all over the roster, Spink was only there to see the first pennant; he left the club after the 1885 season, determined to start a weekly newspaper that would report exclusively on sports. Even there, his support for the local teams never flagged. Indeed, he later came to personally loathe Von der Ahe, a sentiment stemming in part from his disappointment over the fact that, having done so much to boost the fortunes of both the city itself and its baseball community, Von der Ahe had in Spink’s opinion squandered the accumulated good will, and let the city down.20

Why exactly Spink decided to found The Sporting News remains unclear. Some have pointed to a conversation he had with fellow St. Louis reporter (and later publishing powerhouse) Joseph Pulitzer, who reportedly told Spink, “Given a good business manager and an editor who can really write, any newspaper should fast become a good paying institution.”21 But whatever the reason, in typical fashion, Spink turned his considerable energies to creating a paper that would soon be recognized as a leader in the field.

The first edition of The Sporting News, an eight-page offering, was available to the public on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 1886, at a price of 5 cents, with those who were optimistic about its survival able to secure a yearlong subscription for $2.22 At the time, the nation boasted just one other sports-only offering, Sporting Life, based in Philadelphia. While recognizing the competition, the publicist in Spink did not wait long before boasting that The Sporting News had the highest circulation of any sports-only paper west of the City of Brotherly Love.23 Despite its reputation as a sports-only publication, in the early going the paper in fact reflected both Spink’s varied interests and his desire to broaden the paper’s circulation, seeking in particular to appeal to what sport historian John R. Betts termed the “‘barroom fraternity,’ gentlemen of leisure interested in politics, theatre, and sports.”24 While baseball coverage was the centerpiece, columns entitled “The Wheel,” “The Gun,” “The Stage,” “The Ring,” and “The Turf” provided readers with news about an array of other activities, including rowing, horse racing, hunting and fishing, bicycle racing, boxing, theater, and even billiards.25 In fact, while baseball was the original focus, it was only after his younger brother Charles had assumed full control of the paper that it focused exclusively on baseball.26

The Sporting News was an immediate success, but the multiplicity of tasks involved in running the paper soon taxed even Al Spink’s considerable energies. Consequently, recognizing both his own weakness and the wisdom of Pulitzer’s advice, he persuaded his younger brother Charles to give up the homesteading venture he had been pursuing in South Dakota to join him in St. Louis and assume the position of business manager at the princely sum of $50 a week.27 It was, at least initially, a perfect pairing. The passion for the game that his younger brother lacked was more than made up for by a business acumen that was manifested in countless ways, and quickly helped turn the paper into a baseball centerpiece. Between securing advertising and expanding circulation by distributing each edition to all parts of the country – and sending the unsold copies to news dealers as samples – he raised the profile of the paper, and helped further expand awareness of the game it served. To further aid in that effort, Charles persuaded a number of minor leagues to name The Sporting News their “official organ,” a designation that helped secure the young paper’s place in the baseball establishment.28

Al, meanwhile, continued to handle the editorial side, making the paper must reading for an increasingly sports-hungry public. But things changed in 1890 when The Sporting News, after first breaking the story about the player revolt, then came out in support of the Players’ League, a single-season effort intended to help the players wrest control of the professional game from the owners.29 When the ill-fated plan went awry and the league collapsed, The Sporting News, its relations with the baseball establishment consequently strained, suffered as well. His interest in the paper waning, Al turned control of the paper over to Charles, leaving it to him to stop the publication’s slide.30

Al then turned his energies to one of his other passions, theater. He was determined to write and produce a play that he intended to bring to a national audience. The venture represented a drastic change of focus, but he poured both his energies and his assets into the theatrical production, and in 1891 began work on what would become a three-act play, The Derby Winner.

A romantic comedy, the show was a tale of a cash-poor character named Milt West who was determined to race his mare, Missouri Girl, in the St. Louis Derby, all in an effort to make enough money to pay for his approaching wedding. However, when his fiancée, Alice, gets wind of his “relationship” with the Missouri girl, things take a turn for the worst, and the effort to undo the damage only exacerbates things. In the end, Missouri Girl wins the race, giving Milt the funds he needs for the wedding, and he is finally able to convince Alice that she is his one and only love. But the path to happiness is one fraught with drama. So too was the production. For while the story was comparatively straightforward, if not trite, the showmanship and the staging of a spectacular that included a cast of 42 humans, as well as a number of horses (animals who “ran” the derby on a treadmill onstage), made for a singular and extravagant viewing experience, as well as a costly production. And of course, such a venture was not without its risks; the horses, in particular, were often a problem.31 The play itself debuted on August 25, 1894, at the St. Louis Grand Opera House. Befitting Spink’s earlier career in journalism and public relations, the premiere was accompanied by no small amount of fanfare.32

After an enthusiastic response in St. Louis, Spink decided to take the show on the road, subsequently playing in Baltimore, Chicago, Cincinnati, Kansas City, Lawrence (Kansas), Louisville, Nashville, Washington, and Wheeling, while also doing repeat shows in St. Louis.33 In March of 1896, Spink sold the rights to The Derby Winner to a St. Louis sportswriter and one-time secretary, business manager and part-owner of the St. Louis Browns, George Munson, who had left baseball to manage the show during its travels.34

Despite numerous good reviews, as well as advertisements for the show that claimed that The Derby Winner was the “most successful racing and comedy drama ever staged with a race track as its theme” (which it may have been), it was subsequently revealed that in fact Spink lost almost a quarter of a million dollars over the course of the effort.35

It proved to be a devastating financial disaster for Spink: Not only was he forced to return to the newspaper world, but he also had to sell the shares of The Sporting News that he had put up for collateral for the show, thus ceding control of his creation to his brother.36

Indeed, in the aftermath of the financial setback that The Derby Winner represented, Spink sought comfort and refuge in a return to the newspaper world, and specifically The Sporting News. However, between the altered business relationship with his brother and his dismay at the continuing struggles the paper was experiencing in the aftermath of its misguided support of the Players’ League, the situation soon proved untenable.

Al derisively termed the paper “The Sporting Death,” and while he put in a short stint helping his brother revive the venture and reverse the decline in revenue and advertising, the experience marked the beginning of a deep family rift.37 It got so bad that Al sued his brother in early 1913, claiming that he was owed considerable funds based on an agreement signed in 1895 to divide the profits earned in the succeeding 15 years.38

The suit never went to trial, but it only exacerbated the already gaping filial breach, one that would only be repaired in April 1914 when Charles was on his deathbed.

The brothers, who together had built and developed a journalistic institution that had done much both for the game and for St. Louis’s reputation as the country’s leading baseball city, were able to reconcile in a tearful deathbed reunion. And whatever the nature of his grievance, all seemed to have been forgotten when Al accompanied the report of Charles’s death in the next edition of The Sporting News with a piece headlined “An Elder Brother’s Tribute” that lauded Charles’s skillful efforts and business acumen.39

In that same familial vein, when Charles’s son John George Taylor Spink, who went by J.G. Taylor Spink, succeeded his father as publisher, Al offered strong support. Indeed, in 1925 when Taylor wrote Al seeking his thoughts on the state of the paper, Al’s comments said much about how he viewed his long-ago creation. He opened the three-page letter declaring, “I feared that the one paper I was so proud of would fall from the fine level he (Charles) had established for it,” before offering a detailed mix of analysis, constructive criticism, and praise for the paper, as well as for the efforts of his nephew.40

Indeed, the aging Al closed with some fatherly advice: “Take sunshine to your office each day and bring it home with you at night. Make those who work for you love and respect you and bring your children up in the same way. Do those things, dear boy, and many happy days are in store for you.” He signed the letter, “Dad.”41

In fact, that response was reflective of an important aspect of his life. Alfred H. Spink was also a family man. He was married twice, his first wife dying only two years after they were married.42 He also had four children, three sons and a daughter. One of those children, William, was at the center of an incident that once left Spink on the brink of death.

While at work at his office on New Year’s Eve 1907, Spink, at the time the president of the St. Louis World Publishing Company and editor of the St. Louis World newspaper, the publication he had started just a few years before, heard a quarrel outside his office. He emerged to find his son engaged in a scuffle with one Victor D. Grow, a printer and sometime employee of the paper, who had apparently come to the World’s office to pick up a check for some back wages.

Spink later said that when he entered the room, Grow was standing in front of William, aiming a revolver at the younger man. Spink then rushed forward intending to disarm Grow, but Grow quickly changed direction and, with the men separated by about four feet, Grow fired twice, hitting the 53-year-old in the side. The bullet entered, according to one report, at the ninth rib and apparently lodged in the abdominal cavity.

While Grow surrendered quickly to police, Spink was rushed to the hospital. The bullet could not be found initially, and doctors were pessimistic about his prospects, but after a full day’s hospitalization they began to predict a full recovery. After a few weeks in the hospital, Spink was released, whereupon he took a trip west to regain his health.43

Later that year, with final preparations for Grow’s trial underway, Spink urged prosecutors to drop the charges. Saying he believed that Grow “was not in his right mind when he fired the shot,” Spink asked for mercy, a request prosecutors were initially reluctant to grant, but ultimately did, ending the dramatic chapter in the editor’s life.44

In 1910 Al Spink published the book The National Game, an effort that, paired with his earlier founding of The Sporting News, cemented his status as a central contributor to the literary and historical record of baseball. The book included biographical profiles and a trove of statistical information, as well as illustrations, all of which combined to provide readers with a comprehensive picture of the many people whose efforts on and off the field had shaped the game’s early history.

It also revealed Spink’s deep commitment to the game, as well as his vision for the sport that he had helped shepherd to a place at the forefront of the American sports consciousness. Indeed, his view of the game was evident in his dedication, in which he shined a spotlight on the people who, for Spink, made baseball special, writing, “I dedicate this book to the professional base ball players of America, to the silent army, to the force that is on the field to-day and to the legions that are to follow in years to come.”45 He added, “I want this book to live forever, so that the names of those who helped to build up and make base ball the greatest of outdoor sports may never be forgotten.”46

The comprehensive volume, a work that foreshadowed the cottage industry that is the baseball-book business, was well received upon publication. The New York Times observed that it had “great autobiographical value” as well as “many pages of valuable statistics, which greatly enhance its value.” Praising its “vast amount of research work,” it called the book the “most complete book of reference that has ever been written on the game of baseball.” The Times also noted that the book had been given the official endorsement of the American League at its annual meeting.47

The St. Louis Globe-Democrat also praised the effort, asserting that it was “nothing more nor less than a history of baseball, containing a story of most of the happenings of the game since it was first played up to the present time.” Terming it “the only standard work of the kind ever published,” it observed that it “promise[d] to become a permanent fixture in every well-regulated library.”48

Upon its rerelease as part of the Southern Illinois University Press’s Writing Baseball series, the book was hailed as “the first important history of baseball, predating Albert G. Spalding’s better-known America’s National Game by a year. As noble as Spink’s goal of having the book live forever may have been, the book was in fact out of print from 1911 until its re-release in 2000. Upon that re-release, Writing Baseball series editor Richard Peterson noted that in contrast to the competing volume published by Spalding in 1911, a work that told “the story of the moral triumph of the courageous and honest magnate over greedy and crooked players,” Spink’s effort “celebrates the accomplishments of the ‘great players who helped bring the game into the prominence it now enjoys.’”49

In December 1914 the St. Louis Globe-Democrat reported that Spink had taken a job with a San Francisco paper, leaving behind the place he had called home for almost five decades.50 But while he may have been officially tied to San Francisco, in fact in the years after his brother’s death he appears to have thrived as a freelancer, a prolific and broadly based writer on the full array of sports that had captivated him throughout his long, if occasionally interrupted, journalism career.

Indeed, his byline appeared in papers from coast to coast, and north and south, on subjects ranging from reflections on baseball to reports on the current state of boxing. He reported and offered commentary, both of the moment and with a historical perspective that was both learned and personal. And even if much of the country was unaware of his Canadian roots (one article that noted his longtime relationship with Charles Comiskey stated that Spink had been born in Chicago, but had moved to St. Louis as his journalism career was getting under way),51 he did not forget his native Canada; his articles were just as likely to appear in the Winnipeg Tribune or the Saskatoon Daily Star as they were in the Buffalo Times.52

A favorite was the Reno Gazette-Journal, which not only included his regular reports on boxing but also featured his column, “The Sportsman’s Corner.”53 He had a similar forum in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, which hosted “Al Spink’s Column.”54 As well, the Salt Lake Tribune, the Birmingham (Alabama) News – where he was listed as one of their “news sports experts” – and the Mount Carmel (Pennsylvania) Item were among those publications that regularly featured Spink’s work.55

From a nostalgic look back to 1919 and the first time the White Sox and the Reds had battled for a championship, to a hard-line discussion of what should happen to the Black Sox who emerged from that World Series, to a more whimsical look at heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey’s short-lived theatrical career, the stories flowed.56

To the delight of readers everywhere, Spink offered a wide range of articles that reflected his writing and reporting skills and his insatiable curiosity, not to mention the wealth of knowledge and perspective he had gained over the course of over five decades in the newspaper business. In addition, in 1921, he published a three-volume series entitled Spink Sport Stories: 1000 Big and Little Ones, a collection that included a wide range of stories from Al’s decades in the sports world.57

Meanwhile, Spink’s reverence for the game and its history led to his helping found an organization in Chicago, the Old Timers’ Baseball Association, for which he served as secretary. Begun in 1919, it sought to “revive the baseball spirit of the day gone by and especially to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the organization of the Chicago White Stockings as a professional team.”58

The group was a fitting reflection of Spink’s love of the game as well as the esteem in which he held the game’s pioneers, a feeling he had made clear in his book, The National Game. After his death in May of 1928, Association members were well represented among the attendees at his funeral.59

Spink’s wife, Bertha, died on November 5, 1926, and the reports of her death indicated that the aging baseball writer was himself ill and at home.60 Consequently, Spink’s death on May 27, 1928, in Oak Park, Illinois, outside Chicago, was not a total surprise, but it was nevertheless one widely recognized by the baseball world.61 Indeed, befitting his stature in the baseball community, the eulogy at his funeral was delivered by no less a luminary than Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis.62

With The National Game and The Sporting News, not to mention his extensive and wide-ranging journalistic efforts, Spink left behind a written legacy he could be proud of. In an interesting twist of fate, however, very soon after his death, his words made news in another area, when it was revealed that he had left behind a potentially explosive affidavit.

In the document, which had been embargoed and authorized for release only after his death, Spink shared information arguably exonerating radical labor leader Tom Mooney from the Preparedness Day parade bombing of 1916, for which Mooney was then serving an extended prison sentence in San Quentin Penitentiary.63

While the Federation of Labor voted to use the new evidence to seek Mooney’s release, their hopes were ultimately dashed, and it was not until January of 1939 that Mooney was released and pardoned by California Governor Culbert Olson. The pardon brought an end to a case that had been a high-profile cause célèbre for some of the nation’s most prominent liberal and radical forces, who had asserted that Mooney had been framed.64

Over the course of a full life, Alfred H. Spink was a journalist, an entrepreneur, a publicist, a businessman, and a sportsman, one whose involvement in baseball represented a way to manifest all those traits while also reflecting a view of the game that would only be fully realized decades later.

While a quixotic and sometimes mercurial individual, Al Spink nevertheless left an indelible impact on the game of baseball. No one can deny the importance of The Sporting News to the growth of the national pastime, not to mention its role as the chronicler of a game whose history is captured in the words and numbers that the paper so faithfully shared with its readers over the years.

Similarly, his book The National Game represents one of the earliest efforts at illuminating the game’s history, serving as both an example and an inspiration for generations to come. In all of these efforts, Spink showed himself to be a visionary, although one with a short attention span who laid out his vision before leaving it to others to implement. The many shifts and short term “careers” he enjoyed reflected this multifaceted approach to life.

Indeed, while The Sporting News, The National Game, and his years as a sportswriter tend to dominate perceptions of Spink’s relationship with and influence on the game, his years with the St. Louis Browns before he left to found The Sporting News are no less noteworthy, while also providing context for his journalism and writing efforts.

In the end, over the course of a lifetime in and around the game, Alfred H. Spink impacted in no small way both how the sport developed and the way in which it was perceived and embraced by the American people. No small legacy for a Canadian-born immigrant who traded in his cricket bat for a baseball one when he was not yet in his teens.

Notes

1 Steven P. Gietschier, “Leading Off: The First Years of the Sporting News Archives,” Provenance, Journal of the Society of Georgia Archivists, Volume 7, No. 1, January 1989: 42.

2 Mark Cooper, “Alfred Henry Spink,” in Frederick Ivor-Campbell, Robert L. Tiemann, and Mark Rucker, eds., Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996), 156; “Alfred Henry ‘Al’ Spink, Sr.” Find a Grave; https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/83037142/alfred-henry-spink. Spink’s baptismal certificate gives the 1852 date.

3 Steven P. Gietschier, Foreword, in Alfred H. Spink, The National Game, Second Edition (Carbondale and Edwardsville: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000), lxiii.

4 An interesting family tie is that between the Spinks and longtime baseball historian Ernest J. “Ernie” Lanigan. One of Al Spink’s sisters, Frances Elizabeth, married George Thomas Lanigan. Their son Ernest was born in 1873 in Chicago.

5 The 1866 Quebec city directory lists William as a member of the legislative assembly, although his official title was clerk of routine and records.

6 Steven P. Gietschier, Foreword, lxiii.

7 Mark Cooper, “Alfred Henry Spink.”

8 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiii.

9 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiii.

10 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiii.

11 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiii.

12 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiii.

13 “Ghastly Grenada,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, September 5, 1878.

14 “Latest News: The Yellow Fever Still Rages with Unabated Fatality,” Nebraska State Journal (Lincoln), September 3, 1878.

15 Chris Von der Ahe (1851–1913), Missouri Encyclopedia; https://missouriencyclopedia.org/people/von-der-ahe-chris.

16 J. Thomas Hetrick, Chris Von der Ahe and the St. Louis Browns (Clifton, Virginia: Pocol Press, 1999), 5.

17 Hetrick, 5-8.

18 Hetrick, 9.

19 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiv.

20 Hetrick, 287.

21 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “Introduction,” The Sporting News: The First Hundred Years 1886-1986 (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1985).

22 Steve Gietschier, “The Sporting News,” SABR BioProject, https://sabr.org/bioproj/topic/the-sporting-news/.

23 Lowell Reidenbaugh, “A Lucky Day Back in 1886,” The Sporting News: The First Hundred Years 1886-1986, 14.

24 Steven P. Gietschier, “Leading Off: The First Years of the Sporting News Archives.”

25 Lowell Reidenbaugh, The Sporting News The First Hundred Years 1886-1986, 15.

26 “A History of The Sporting News[,] the Oldest Sports Publication in the U.S.,” collectinggoldmagazines.com; https://collectingoldmagazines.com/magazines/sporting-news/.

27 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiv.

28 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiv.

29 “A History of The Sporting News.

30 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiv.

31 “Alfred Spink’s ‘The Derby Winner,’” Ahead by Three, https://aheadbythree.wordpress.com/2016/11/20/alfred-spinks-the-derby-winner/. Accessed July 7, 2021.

32 “Alfred Spink’s ‘The Derby Winner.’”

33 “Alfred Spink’s ‘The Derby Winner.’”

34 “Alfred Spink’s ‘The Derby Winner.’”

35 “Alfred Spink’s ‘The Derby Winner.’”

36 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiv.

37 Cooper, 156.

38 “Al H. Spink Sues His Brother for an Accounting,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, January 14, 1913.

39 Lowell Reidenbaugh, Introduction, The Sporting News The First Hundred Years 1886-1986 (St. Louis: The Sporting News, 1985).

40 Reidenbaugh, Introduction.

41 Reidenbaugh, Introduction.

42 “Alfred Henry ‘Al’ Spink Sr.” Find a Grave.

43 “Printer Saved from Going to Jail by the Editor Whom He Shot,” Buffalo Times, November 15, 1908.

44 “Spink’s Plea Saves Printer Who Shot Him,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, November 9, 1908.

45 Alfred H. Spink, Dedication, The National Game, Second Edition.

46 Alfred H. Spink, Dedication.

47 “‘The National Game’ by A.H. Spink,” New York Times, December 19, 1910.

48 “Al Spink Publishes History of Baseball,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, October 13, 1910.

49 “Rare Baseball History Back in Print for First Time Since 1911,” press release, Southern Illinois University Press, April 3, 2000.

50 “Al Spink Accepts Position on Paper in San Francisco,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, December 2, 1914.

51 G.W. Axelson, “‘Commy’ the Grand Old Roman,” Salt Lake Tribune, October 26, 1919.

52 Al Spink, “John McGraw Not Likely to Realize His Baseball Dream,” Winnipeg Tribune, December 16, 1919; Al Spink, “More Stories of the ‘Lucky Dutchman,’” Buffalo Times, July 13, 1918.

53 Al Spink, “Lavigne’s Career in Ring Recalled,” Reno Gazette-Journal, January 28, 1924; “The Sportsman’s Corner Conducted by Al Spink,” Reno Gazette-Journal, January 19, 1919.

54 “Al Spink’s Column,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, December 21, 1922.

55 Al Spink, “Perils and Thrills Attended Travel of Old-Time Ball Clubs,” Salt Lake Tribune, January 2, 1920; “News Sports Experts,” Birmingham News, August 14, 1920; Al Spink, “Sacrifice Hitting Help to the Giants,” Mount Carmel (Pennsylvania) Item, July 17, 1919.

56 Al Spink, “Romance Is Added to Coming Meeting of the White Sox and Cinci,” Saskatoon Daily Star, September 13, 1919; Al Spink, “Al Spink Says Guilty Should Be Blacklisted,” Birmingham News, January 21, 1921; “Theatrical Life Palls on Jack Dempsey,” Mount Carmel Item, October 6, 1919.

57 Gietschier, Foreword, lxiv-lxv.

58 “Baseball Fans of ’69 Make Plans for ‘Golden’ Dinner,” Chicago Tribune, October 26, 1919.

59 “Old Time Players,” Cincinnati Enquirer, May 30, 1928.

60 “Mrs. Al Spink, Wife of Sports Writer, Dies,” Los Angeles Times, November 6, 1926.

61 Mark Cooper, “Alfred Henry Spink,” 156.

62 Gietschier, Foreword, lxv.

63 “Dead to Mooney’s Aid,” Kansas City Star, June 4, 1928.

64 “Tom Mooney,” Spartacus Educational; https://spartacus-educational.com/USAmooney.htm.

Full Name

Alfred Henry Spink

Born

August 25, 1853 at Quebec City, Quebec (Canada)

Died

May 27, 1928 at Oak Park, Illinois (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.